The Science of CTE

You can help advance the understanding of CTE by participating in research.

Brain cells 101

CTE is a disease of the brain. To really understand the science of what’s going on, you’ll need some background on what the brain is like when it is healthy. A good place to start is by looking at our brain cells, or neurons.

If you’ve ever heard someone talking about how brains are wired, or if you’ve heard someone talking about getting their brains firing, they were talking about their neurons.

Neurons are the basic building blocks of the brain. About 90 billion neurons form trillions of connections, creating a complex network that allows us to interpret and react to our environment.

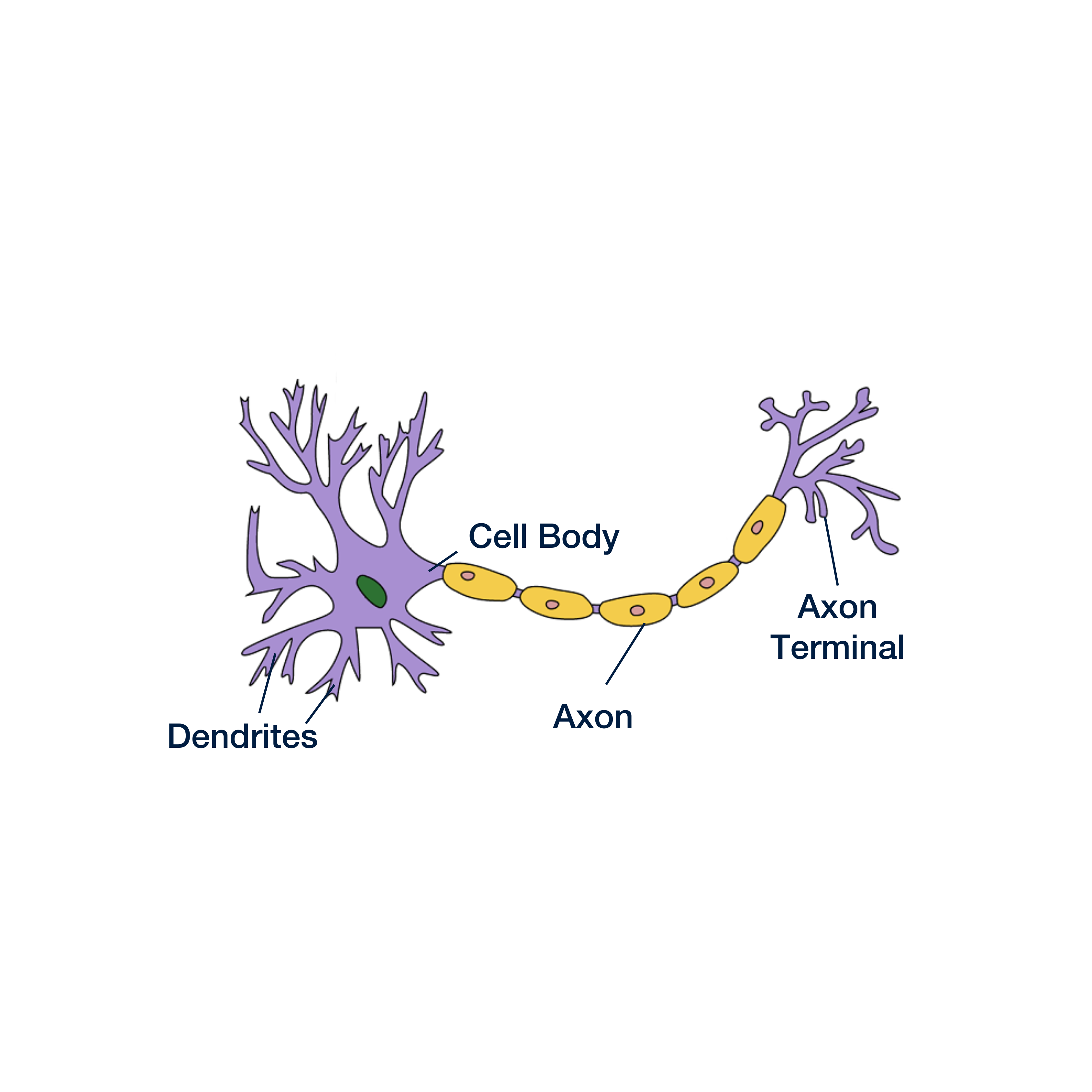

Every neuron has three main parts: the cell body, the axon, and the axon terminal. We’ll focus mainly on the axon, which is a long and skinny structure that behaves a lot like a wire in an electrical circuit. Neurons communicate with one another by sending electrical signals down their axons and off to adjacent cells.

Problems with the neuron

The axon’s long and spindly shape helps the neuron reach far away cells in different parts of the brain, but there are two problems that come with that shape:

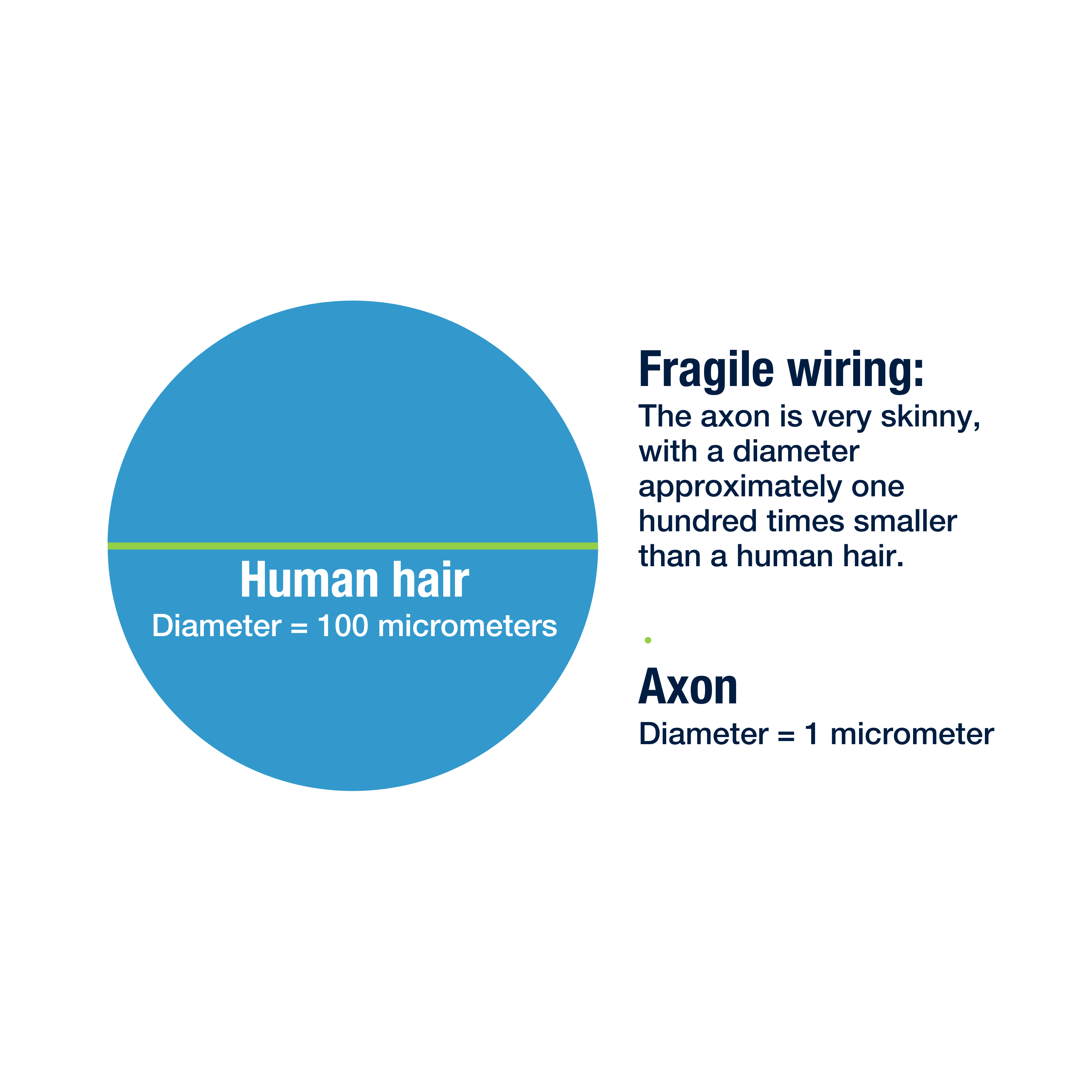

1. It makes the axons fragile, and prone to injury during concussion.

Things tend to break at their weakest point, and the axon is very often the weak point for the neuron. After a concussion, damage to axons is much more common than damage to other parts of the cell. A damaged axon has more trouble sending its signals, interfering with the brain’s ability to do its job.

2. It makes it difficult for the cells to distribute chemicals and materials to all areas of the cell.

Almost everything the cell needs to function is made in the cell body, but a lot of that stuff needs to be used along the axon or at the axon terminal. To get everything where it needs to go, the cell needs a transportation system.

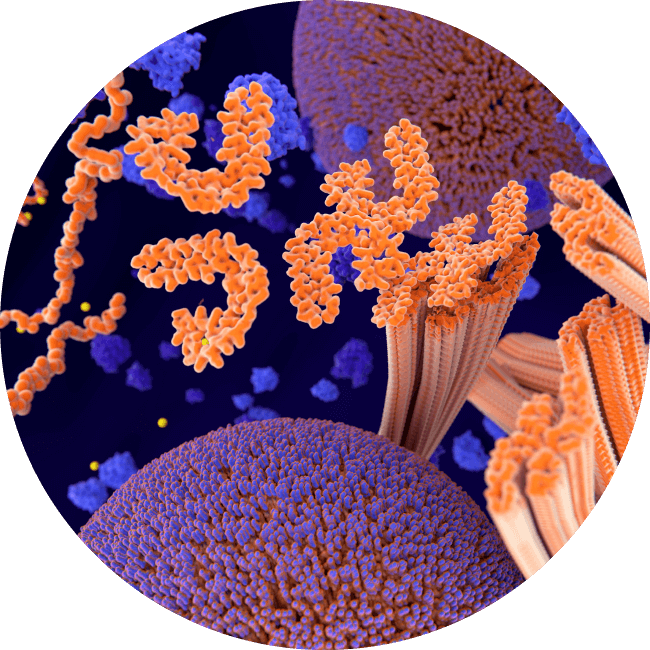

Microtubules: a fragile transportation system

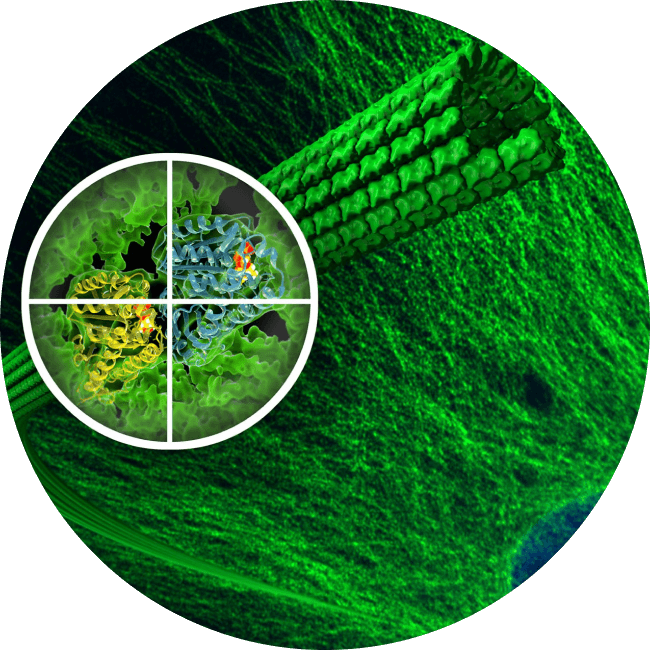

To help distribute molecules and materials throughout the cell, neurons have a special transportation system, made up of tiny tubes called microtubules. These tubes run the length of the cell, helping materials from one end make it down to the other end.

To continue with our example, if the axon were as big as a regular wire, each microtubule would only be as wide as a single strand of hair.

Remember: axons are the weakest point of the neuron, making them the first thing to break during a concussion. Microtubules are much smaller and weaker than the axons, making them vulnerable not only to concussion, but also smaller impacts that may leave the axons intact.

Since these tubes are so small, they need help supporting their structure. A special protein called tau helps keep everything together by sticking to the tubes outside. In healthy brains, this is where the story ends: tau supports the microtubules, microtubules help the cells function, and the brain operates normally.

In diseased brains, however, the same protein that helped keep everything together can actually cause things to fall apart.

Tau proteins going haywire

If the microtubules are injured or break down, tau proteins can misfold, detach, and float freely inside the cell. Once proteins start misfolding, even without additional trauma they can cause other tau proteins within the same cell to misfold and malfunction, impairing cell function and eventually killing the cell. The misfolding tau appears to spread to connected cells when they cause those cells to malfunction as well through what is called prion-like spread.

Scientists are still trying to understand why this process leads to CTE in some people and not others. What scientists do know is that the tau in CTE spreads in a distinctive pattern that is unique to CTE. Scientists also believe that the slow spread of misfolding is likely one reason it takes so long for symptoms to show up. The slow spread also provides opportunities for effective treatment to slow or stop the disease.

Future directions of CTE research

One of the biggest questions in CTE research today is: How can we diagnose CTE in a living person? Once this is possible, we can begin evaluating potential treatments and therapies to help people who are suffering from the symptoms of CTE.

Scientists are working hard to develop such a test, and there have been promising findings using a variety of special techniques. Some of the most exciting lines of research are trying to diagnose CTE using:

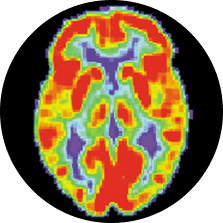

Positron Emission Tomography (PET scans)

Researchers first inject a tracing chemical that binds to the tau proteins in CTE, then use a special brain scanner to trace where the chemical settles in the brain. With a tracer chemical that binds to CTE tau (and only CTE tau), this technique could show us the tell-tale distribution of tau tangles while someone is still alive. Several research groups have developed such a chemical, and early studies in athletes are already underway.

Fluid Based Biomarkers

New techniques in biochemistry have allowed researchers to develop extremely sensitive tests able to detect proteins and substances in the blood at extremely low levels. Researchers using these tests are looking for evidence of abnormal tau and other indicators in the blood of athletes at risk for CTE. Normally these indicators would be caught by a robust barrier between the bloodstream and the brain (called the blood brain barrier), but repeated concussions and nonconcussive impacts that cause CTE can also damage this barrier, allowing clues to slip out of the brain.

Understanding Risk Factors

Another major field of inquiry is understanding risk factors for CTE and CTE progression – why do some people get CTE while most do not, and why do some people appear to have worse symptoms associated with CTE?

Genetics play a role in every major neurodegenerative disease. Together with our American collaborators at the BU CTE Center, directed by Dr. Ann McKee, we published the first CTE genetics study, which found that among those diagnosed with CTE, a variant of TMEM106B was associated with a 2.5 times greater risk of dementia. However, they did not find an association with developing CTE pathology, supporting the hypothesis that brain trauma exposure is the primary risk factor for CTE.

As the CLF Global Brain Bank grows, our ability to detect the influence of genetics on CTE pathology and symptoms will grow exponentially. Understanding the genetics of CTE will provide insights into why CTE occurs and how it progresses, creating better targets for interventions and treatment. You can support that effort by joining the CLF Research Registry. While the science isn’t there yet, in the future, genetic profiles may help us identify children who should not be exposed to contact sports.

Here in Australia, we collaborate with the Australian Sports Brain Bank (ASBB). The ASBB has published several studies that have revolutionised what we know about CTE in Australia. You can view their publications here.