People don’t understand how at the age of 30 I have concussed myself into having a neurodegenerative disease. Trust me, if it wasn’t happening to me, I wouldn’t believe it either, but at an unknown rate my brain is declining and dying.

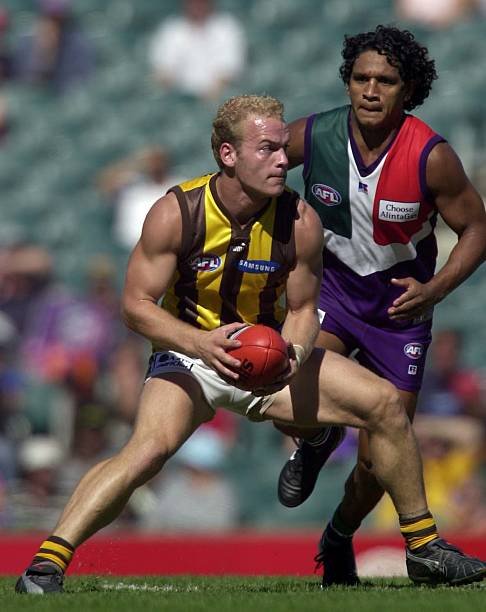

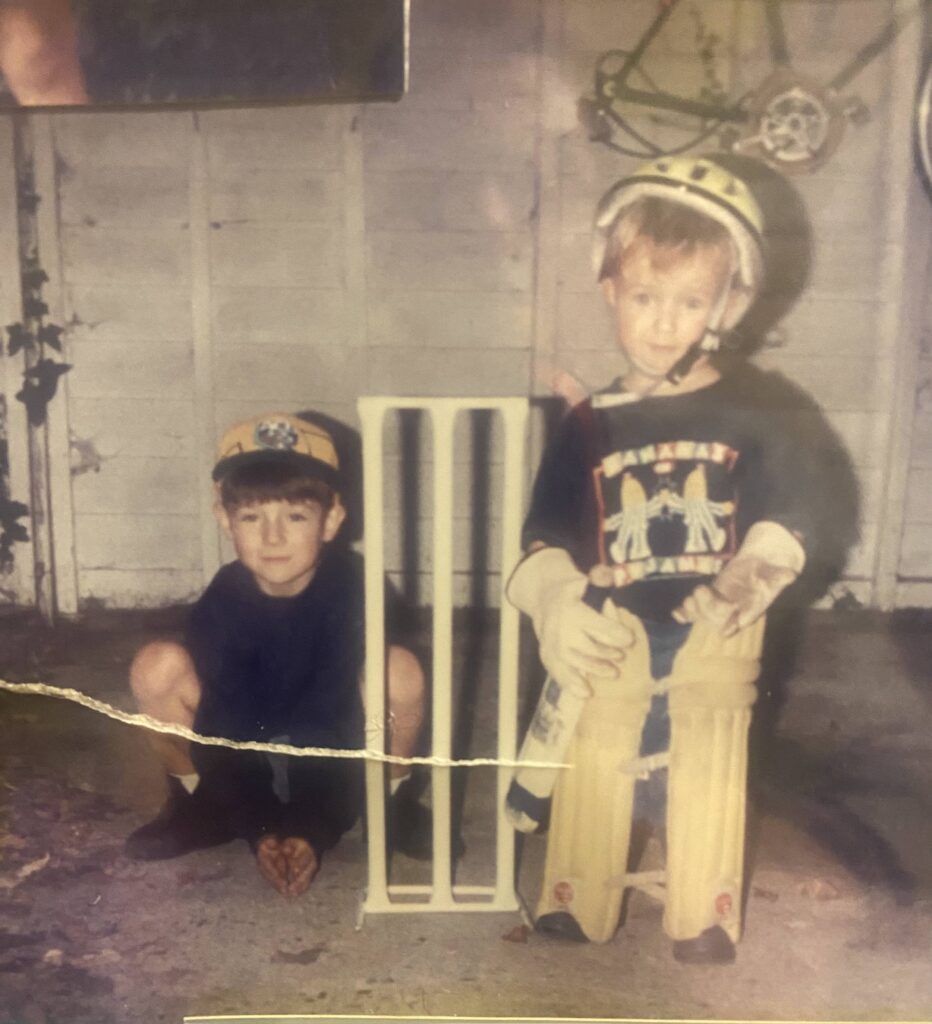

I was 26 when I was selected to play in Bond University’s elite women’s AFL program – QAFLW (Queensland’s top league under ALFW).

After suffering seven concussions in three years – I was forced to medically retire. My life has completely changed as a result of the head injuries I sustained playing sport and I now want to raise awareness of the ‘invisible disease’ I live with.

There was 10 minutes left on the clock, it was my first preseason game with QAFLW, I was wanting to make an impression, so I took a diving mark. In that moment I copped a knee to the head and was out cold for a minute or so.

The game wasn’t on the line (we were 50 points up) and in the words of my coach, ‘I had no reason or right to take that mark’. Some people may call it stupid but that’s how I played and to him what I displayed in that moment were qualities you cannot teach an athlete, so I was invaluable. Later, I found out that mark was the sole reason I was selected in the program. In hindsight, it was the beginning of the end.

I played our opening round the very next week after surprisingly only suffering symptoms for about 48 hours. Throughout that season I received another 3 concussions. One quite sickening to the point some of my teammates still say, ‘we thought you were dead that day’. After each I trained and played within a week or two. There were no strictly imposed protocols or rehab programs for me to follow or for concussions in general. It’s a self-reported injury and I was able to get away with not being completely honest about how I was feeling as the symptoms didn’t concern me. Seemingly I was able to bounce back to ‘normal’ quickly.

My fifth concussion came early in my second year from a sling tackle. It was overlooked by a serious neck injury that nearly left me a quadriplegic. I sat out the rest of the season and during this time, I started to notice changes in my memory. I had brain fog, dizziness, nausea, migraines, headaches and was constantly fatigued. I felt horrible all day every day, nothing helped alleviate the pain and symptoms. I saw physiotherapists, doctors, specialists in different fields and they believed my symptoms were due to the neck injury, the spinal cord swelling and the vestibular dysfunction and in time I’d feel better if I continued with the neck rehab.

I wanted to believe their advice and that it was just my neck but part of me knew there was a much bigger problem as I started to feel less like myself. But like most athletes, I blocked it out, buried the feeling and the day I got cleared to train again I started.

In preseason, I really began to struggle – I was making uncharacteristic errors, I was slower with my fundamental skills and reactions, I was fatiguing quicker and struggling to understand the drills and the game. I suffered my sixth concussion from a heavy tackle in training, which drove my forehead straight into the ground. I laid face down for a minute or so, dazed, and unable to communicate but I stumbled up, kicked a goal, and played it off. As I walked to our treatment room, I was dizzy, nauseous, my legs were like jelly and my vision was blurred. The pressure in my head and the instant headache was intense. I knew I was concussed but I also knew I could ‘act’ and ‘convince’ the right people that I was fine as I did not want to want to miss another training session or game and be seen as a liability to the team because I was always ‘injured’.

I played four days later, and I struggled significantly to comprehend the game and my overall performance was poor. I couldn’t follow the flight of the ball and keep up with the game – it was like I was in slow motion and the game was being played at 10 times the speed. Whack! A shoulder to the side of my head. My seventh concussion in 3 years.

In the months that followed all my symptoms – headaches, migraines, pressure in my head, brain fog, nausea, dizziness, blurred vision, lack of memory, mood, fatigue, light and noise sensitivity – seemed to accelerate and intensify. Noise would irritate me, I couldn’t focus, make a decision, process new information, read properly, have the lights on in the house and remember simple things. I would have to rest after only being awake for a few hours as I was completely exhausted.

As much as I tried to hide it and act fine, I was becoming a completely different person quickly. My personality started to change, my cognitive functions were slower, my concentration, my speech and my brain’s ability to process most things became affected. I battled extreme mood swings, impulsive behaviours where I’d suddenly snap and destroy whatever was in front of me. Anxiety, depression, and constant suicidal thoughts became nearly impossible to drown out. I felt I was living in a body and mind that was hijacked. It was a living hell.

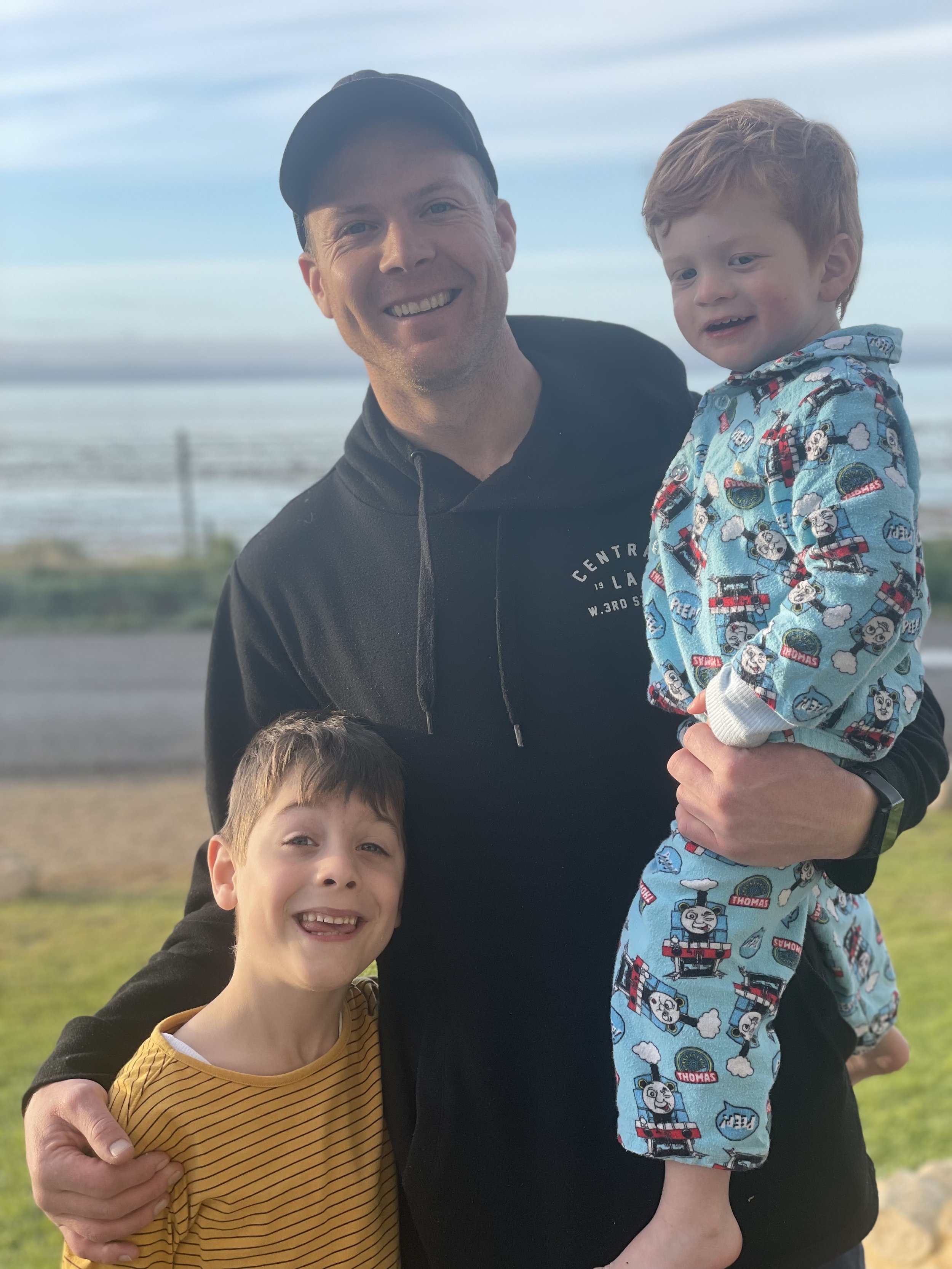

As there is no specific rehab, treatment, or cure – two years after retiring from AFL I am still suffering daily a constellation of these symptoms. Because of my experience, I want to contribute to the concussion conversation. It’s the reason I’m sharing my story and have become an Advisory Committee Member for the Concussion Legacy Foundation Australia.

I want sport to be safer for everyone – I want to help create strict protocols for all levels, age groups and genders and see some of the decisions taken out of the players hands. There is no room for grey area in concussion, it needs to be black and white.

I want to drive change in awareness and education. I want to help players of all ages, genders and levels feel empowered to speak up (without judgement or punishment) and say ‘I’m not ok’ if they feel as if they have a concussion. I want to help change the perception that concussion isn’t a serious injury and instead, ensure it is treated like one.