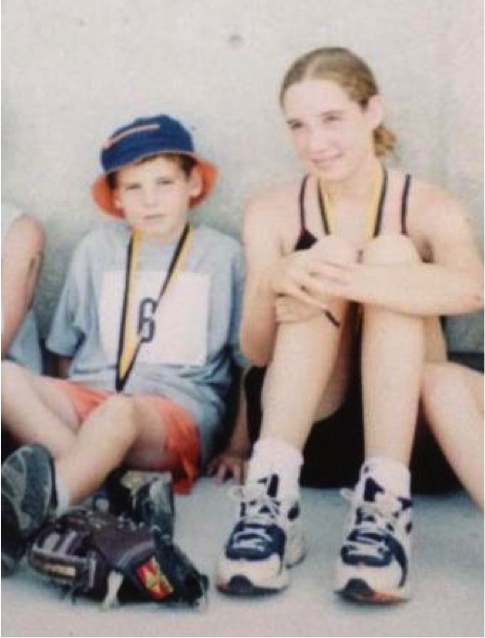

A Talented Athlete Since Birth

Bruce McMillan was born on June 26, 1950, in Northern Ontario, where hockey was a way of life. He started playing the sport at an early age on outdoor rinks, and his athleticism was apparent even during youth. Bruce played Junior A hockey with the Soo Greyhounds, then picked up football in junior high school. After playing both sports at Mount Allison University, he was the first draft pick for the CFL’s Ottawa Roughriders in 1973.

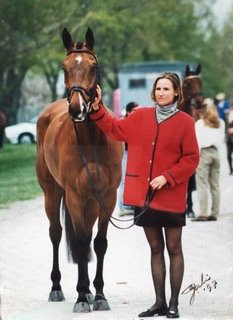

Once Bruce’s playing days were over, he worked various jobs including high school teacher and principal, appraiser, real estate agent, and ice rink manager. In his free time, Bruce was an avid tennis player and fisherman. But his most important role was that of a husband and father to four wonderful children. The love he showed to his family had no boundaries. He was blindly loyal, fiercely intense, and exceptionally hard working with a high EQ.

Bruce’s competitive spirit was matched only by his commitment to our local community. He continued to stay involved in sports by coaching numerous teams in hockey, football, and basketball, sharing his knowledge with countless young athletes. Bruce’s dedication to mentorship throughout his life made a lasting impact on all the youth he worked with, instilling them with confidence, resilience, and purpose.

The Effect of Brain Injuries

Bruce had a number of concussions before the age of 18; our family and friends have counted at least 11. That number grew as he continued to play contact sports in university and professionally. He experienced headaches, but never migraines. Throughout his life, Bruce also suffered from bleeding ulcers; a result, perhaps, of trauma from his childhood.

We really noticed Bruce starting to act impulsively in his late 40s. By the time he turned 60, his loss of memory was evident, and his mood and behavior changed drastically. He became aggressive, totally egocentric, and was easily angered. During our daily five mile walks, Bruce would get in the faces of strangers and frightened a number of people. His driving was erratic and he became involved in a fender bender, forcing us to take his license away.

Bruce had trouble staying still and would wander around, always trying to escape from our home. We had to keep a GPS device on Bruce at all times, and eventually even put locks inside our doors, requiring codes to leave.

Bruce’s decline affected our family greatly. His grandchildren were nervous to be around him, even fearing him at times. Some days he would be the fun Papa, but mostly he would have absolutely no patience with them. It was heartbreaking to watch.

For 13 years, I tried my absolute hardest to keep Bruce safe at home, until he was hospitalized for the last three weeks of his life. He became out of control and needed more help than I was able to provide. He had to be restrained in a bed to keep from escaping and potentially injuring one of the medical staff.

A Continuing Legacy

We found out about the Concussion Legacy Foundation a few years ago while trying to find help online. I signed up for their emails and went through all their resources, becoming convinced Bruce was suffering from suspected CTE. I saw the decline of my mother from Alzheimer’s and my husband’s journey seemed so different.

I talked to my gerontologist about CTE but somehow found myself explaining the disease to him. He couldn’t explain why Bruce’s CT scans didn’t show much – just a small bit of atrophy, nothing else. I always felt I needed to know if Bruce had the disease, so I called the UNITE Brain Bank on the morning of his death, September 23, 2024, and their staff took over the whole process. It was an incredibly seamless experience.

In August 2025, Dr. Ann McKee contacted our family to confirm Bruce’s diagnosis: he had stage 4 (of 4) CTE. We knew it was severe so this diagnosis did not come as a surprise.

Through Bruce’s Legacy Story, I’d like everyone who met him to know he was a wonderful person. He unfortunately was not able to properly control his thoughts and actions during the last 13 years of life. It wasn’t him; it was the disease taking over. Our family repeated this constantly to each other when he was being difficult. We miss Bruce very much and I know he’d be so proud that his final legacy as a brain donor will contribute to future CTE research.