Posted: February 14, 2017

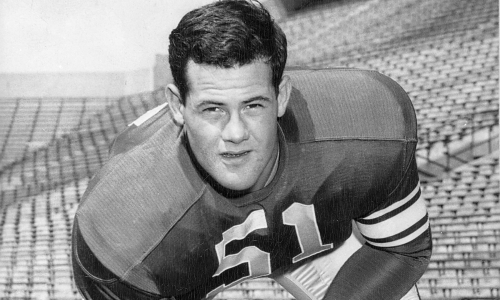

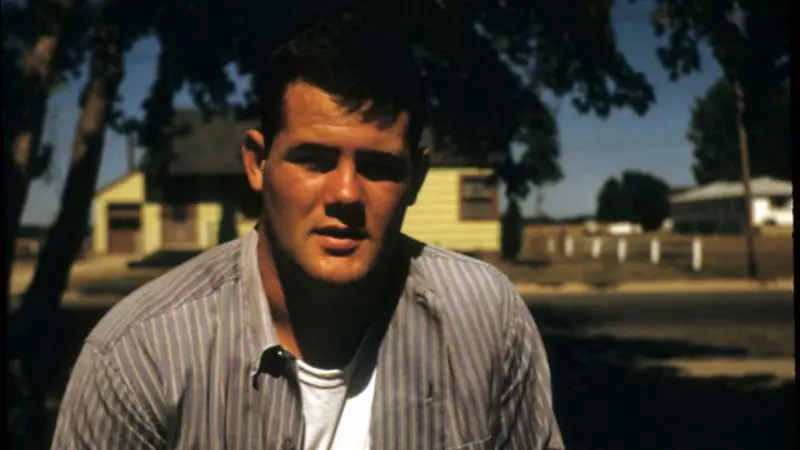

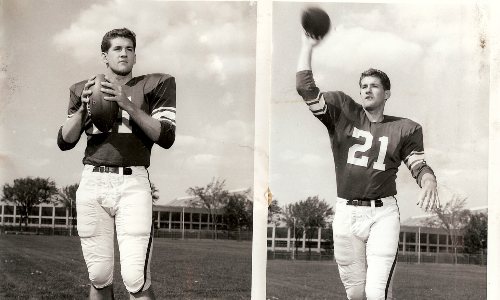

This is the story of my husband, Steve Murra, “bigger than life” dad, husband, coach, friend, and person.

Steve and I met two days before my freshman year of high school. I had just moved to Iowa Falls, Iowa and Steve, who was a junior at the time, had lived there his whole life. We quickly became friends through our involvement in our church youth group. Two years later, Steve shared with me that he had wanted to date me since he met me and I felt the same. We became inseparable, the couple everyone knew and wanted to be – it was always Steve and Jennifer – never one without the other. We were married in 1993, still both in college.

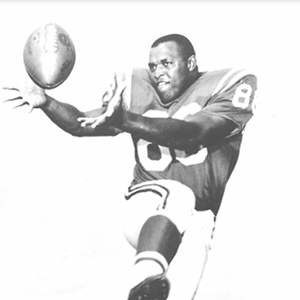

Steve had started playing rugby at age 17 and played for 20+ years, for the local Iowa Falls Rugby Club where his dad was the longtime coach. His passion for rugby developed quickly and he became highly involved in the sport at many levels. He was a student of the game and loved every second of being on the rugby pitch.

In 1994, Steve was asked to start a women’s rugby team at the University of Northern Iowa. Little did we know this would be the beginning of what would define our lives for the next 21 years. Steve began coaching and quickly grew a strong program. He had an uncanny ability to teach rugby to anyone. His players played with their heart and soul and always wanted to make him proud. He believed coaching was not just about teaching the sport, but also about helping his players grow as people and learn to be strong women. I started out managing the team and then became his assistant coach – we did everything rugby together. Highly successful as a coach, Steve not only had fun coaching, but made it fun for the team all the while instilling a desire to win. Steve’s coaching record was strong with an overall record at UNI of 350-51. He coached many players who rose to be highly successful including 3 USA Senior Women’s Eagles & World Cup players, 9 USA U23 Women’s Eagles, 6 1st Team All Americans, and countless players who advanced to local and regional All Star Teams.

Steve was also the Head Coach for the U23 Women’s Midwest Thunderbirds, an All-Star Team encompassing 9 states. He won a National Title coaching that team and went on to take the team on international tours for the past few years.

Our first child, a daughter was born in 2001 and she began traveling with us to rugby events. When our son was born in 2006, he traveled to Penn State for Nationals with us when he was 5 days old. Rugby was our life and it was our family’s life.

Steve was an amazing, loving, caring person who always saw the best in people and always gave everyone a chance. He had a way of making every person he met feel special and accepted. He knew no strangers and made friends everywhere we went. He truly impacted the lives of every person he knew. Steve was hilarious and could make any story sound interesting and typically took over any room he entered. He taught American History at a community college and was a favorite instructor at the school because he made the class fun and interesting at the same time. His passion for teaching and coaching was obvious to anyone who observed him or talked to him about those subjects. Steve was simply a beautiful person.

Through it all, the number one thing in Steve’s life was his family, especially his kids. Steve’s schedule allowed him to spend a great deal of time with his children. He was well known at the kid’s school volunteering for various things and always went on school field trips. He was involved with all the sports in which our kids participated, coaching our son’s flag football team and being the head timer for our daughter’s swim meets. He was an exceptional father and loved his children more than anything.

It is truly difficult to find a way to describe Steve, this bigger than life person. Words that come to mind are: carefree, uninhibited, daring, non-judgmental, unconventional, laid back, calm, funny, adventurous, loyal, accepting, pioneering, determined, witty, generous, smart, women’s rights advocate, compassionate, charming, stylish, thirsty for knowledge, father, friend, and teammate.

Unfortunately, Steve’s personality slowly started to change. I didn’t realize at the time how things were slowly slipping away, but now looking back I can see it clearly. The person who once had unending patience, had a shorter and shorter fuse. The person who was happy and laid back, became angry and uptight. There were long periods of normal behavior and short periods of the angry, unhappy person which slowly turned to short periods of normal behavior and long periods of him being a person I did not recognize. As time wore on, the anger worsened and began to impact most areas of his life. Steve complained of headaches often and took a great deal of ibuprofen. I had countless conversations with him over a period of many years, begging him to get help, asking him what was wrong and why he was so different. He always told me there was nothing wrong or that he was working on trying to make changes. I never saw those changes other than small windows of days when he seemed a bit better.

Steve’s behavior spiraled downward over the course of the last year of his life, very quickly. He chose to retire from coaching at UNI in January 2015 and things spiraled even quicker after that. He went on his last tour overseas in August 2015. During the Fall of 2015, his behavior worsened and he started abusing alcohol. By that point, he was angry most of the time, had become paranoid, and was putting me down to our kids. I discovered he had stopped paying our bills and when I asked him why, his only response was “I don’t know”. In January 2016, I made the hardest decision I ever had to make in my life and asked him to move out of our house because I could no longer tolerate his behavior toward me or the kids. I begged him to seek counseling and make changes so he could come back home.

Never in a million years did I ever think I would ask this person who was so amazing and my best friend, to leave our house. We always planned to grow old together.

Steve always had a special relationship with my parents. He lived with them while I was in college and had nowhere else to live. My parents considered him their son. When I asked Steve to move out, my parents agreed to let him stay there until he could find a place of his own.

Steve died by suicide on February 20, 2016. Regardless of how far he had spiraled, I never thought he would ever do something that would hurt me and the kids so much. This was not behavior anyone would ever expect of the Steve they knew. The news of Steve’s death sent shock waves through the rugby community and our home community. This was a person who loved life and tried to make the most of every day. Unfortunately, my parents were the ones who found him. Their lives will never be the same. My kids won’t go to their grandparent’s house anymore, a place where they previously spent a great deal of time.

As his behavior was worsening, the possibility of CTE came to mind given his years of playing rugby. Steve never had a diagnosed concussion. When I was notified of his death by the medical examiner, I asked that his brain be tested for CTE because Steve taking his life made no sense for his personality.

I truly believe Steve tried his best to get well, but ultimately he knew there was something wrong with him that couldn’t be cured. Now I know, he really couldn’t answer my questions about why his behavior was changing, he really didn’t have the ability to answer.

On November 10, I received the results of the CTE testing and was told Steve had Stage II CTE. I felt so sad for him having to suffer, but I also felt relief at having an explanation as to how this person who I had loved so much and had been with for 28 years changed into a person I didn’t know.

Suicide always has far reaching ramifications. People blame themselves for the person’s death and try to figure out the answer to why. This diagnosis has allowed me to explain to my kids that their dad’s suicide was not because of anyone, it was because he was sick and couldn’t make sense in his head anymore. So many families never get this information and forever wonder why. We have an answer, we have some peace, we miss him every day.

Moving forward

When I initially asked for the CTE testing, I was focused on finding out what caused Steve to change so much and ultimately take his own life. But as I awaited the results from Boston, I began thinking about how having this testing done was also a way for Steve to help others as he had done his whole life, by making this donation to the CTE program. I started realizing the impact it could make if there was some way I could find meaning in this situation by reaching into the rugby community to both increase awareness and to encourage those in the rugby community to make a similar donation.

After I received the results, I felt compelled to tell Steve’s story in hopes it would inspire the rugby community and anyone he may have touched to get involved in this important research. In talking with staff at the Concussion Legacy Foundation, it was clear there needed to be more in-roads to the rugby community and more females involved in the research. I realized I had the ability to help with both of those needs. I talked with my children about what I wanted to do and what I knew Steve would want us to do. They both agreed, telling his story and reaching the rugby community was important and this was a way we could help do that.

Steve was a pioneer for college women’s rugby and led the way for so many women to succeed in the sport. Now my wish is that he will lead the way for the rugby community to help the world learn more about CTE.

I hope someday my kids are able to find meaning in all of this. If we can add to Steve’s legacy by reaching a large number of people, encouraging their participation in the research, and possibly through all of that make a difference, then that is our meaning. There was a time when I didn’t think I would ever stop crying after Steve died, but slowly the tears faded and I was able to see more clearly. I have said through all of this, there has to be some meaning and some purpose is supposed to come out of this – I have been waiting to figure out what that is. I now know, we have found it.

We will never forget…

“The rugby gods are smiling on us today” – Steve’s favorite quote.