Ashley Fulton is a Co-Founder of Women of the CFL and wife of Xavier Fulton, an Offensive Tackle who has played in both the NFL and CFL. We previously interviewed Xavier about his football career and how mental health and head impacts are intertwined. Now you can read about Ashley’s perspective – the supportive loved one and how concussions and mental health affect not just the injured, but those around them too.

What’s it like being married to a professional athlete?

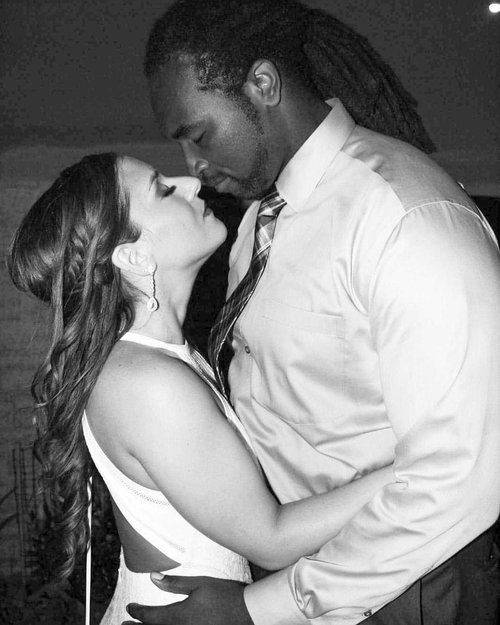

Let me start off by saying how blessed I am to have Xavier as my husband and best friend. I cannot express into words how proud I am of how courageous he is for taking a stand and using his voice as a tool to help others. Going through this together has made us who we are today and it has sealed an unbreakable bond between us. Xavier is my better half and my world is brighter because I have him in my corner.

When I read this question, I struggled on how to answer it. Though athletes are cheered, worshipped and admired for their skills on the field, they’re all just human beings at the end of the day. But when I sat back and thought, ‘what does it take to be a professional athlete?’ I thought about all the time, hard work and dedication, all the blood sweat and tears I’ve witnessed my husband put into a career. It is not your ordinary life.

It differs from a traditional career in the sense that athletes have to combine a mental and physical state of perfection to stand out. Athletes’ days off are often spent at the stadium or in the gym, putting in extra work, watching film, and studying plays. Playing football is a huge part of what most of them live, breathe and eat, and usually from a young age. In Xavier’s case, since he was eight years old. That kind of dedication becomes a huge part of their identity. You learn very quickly that football is the number one priority outside the marriage and family itself.

For instance, training camp is a couple weeks where your husband will be restricted to work for the team at an isolated location. It is the most difficult and dreadful time in any football player’s career. During these intense few weeks he has to master a new playbook and get in CFL shape, while you are at home with very little to no daily communication. You will get the odd 20-minute call from your overly mentally and physically drained husband. During training camp, I tried not to worry. I always knew Xavier was extremely talented and was always signed to be a starter but training camp will have you thinking about his daily performances and the intense demands he was required to endure. I found myself checking all the latest articles written about how he is or isn’t performing, and reading sports forums which were filled with opinions from fans – both positive and negative. Veteran or not, training camp is where your spot is earned. As an athlete’s wife, you’re used to being his biggest support and his biggest motivator and training camp is especially difficult to handle for both parties.

During the football season, events like date nights, personal and family celebrations, nights out with friends, and family BBQ’s become rare. This career path is intensive, it requires demands both on and off the field. A lot of time is dedicated to ensuring they are in shape, focused and prepared. For example, most women marrying an athlete plan their weddings in the offseason. Sounds like common sense? Well I was determined to have a wedding in the summer. We wanted to celebrate our anniversary during the warm months. We chose July 2nd, it was pre-scheduled with the coach as it was to be an off day. As any significant other knows if you lose a game those days off can quickly turn to lengthy practices – and that is exactly what happened to us on our wedding day. They lost the home opener the day before and coach didn’t care what was going on in their personal lives. He called them in, and they had to practice. Two hours after our scheduled wedding time, Xavier and the majority of our guests (the rest of the offensive line) were finally able to make it, and we said our vows. Being married to a professional athlete requires a lot of sacrifice.

Most wives of professional athletes don’t have traditional careers. Being traded to other teams is always in the back of your mind. It is hard to maintain a full-time career, because you may have to uproot with little or no notice. I remember applying to jobs in Saskatchewan during the offseason after Xavier had been traded to Hamilton. I sat in the interview room and was kindly declined from a job I was more than qualified for on the sole reason they knew I wouldn’t be able to commit. Some women would have chosen to stay and do long distance to pursue their career but in our case, Xavier needed me. We needed each other. He was just learning to cope with his depression and anxiety, and I was his support. I knew what I was signing up for when I married him and that is something I will always value. Football careers are short lived. They are just a part of your life before you make that transition into the “real” world where you are then starting your lifelong career. This was a sacrifice I made as I chose to support him though his dream.

I have always been passionate about giving back to the community. With Xavier’s career choice, it’s provided us with a platform to do so. We sat down and talked about his mental health struggle and that by standing up and being a voice to those who haven’t yet been able to come forward, we could make a difference. We chose to be a team and start a journey towards helping others.

I have had to learn to help support, to listen and not be the first to speak and to know how to bring him back to the light when he is feeling dark. I had to learn to know just from the way he walked back to the huddle what mind frame he was in. When you are married to a professional athlete who suffers from depression and anxiety, knowing their frame of mind after a game is crucial. I knew from the way his hands were on the opponent, the way he sat on the bench when defence was on the field or the way he ran down field on a play what mood he was in and how I would need to talk to him after a game.

Being married to an athlete isn’t always a walk in the park but what marriage is? I take great pride in being his biggest support and letting him know that no matter the obstacle big or small we are in it together and he is never alone.

When did Xavier get his first concussion that you remember seeing/noticing? What do you remember about his experience?

Xavier would never tell me when he got a concussion right away. He knew I would have encouraged him to speak to the team doctor/trainer and take proper steps. As an athlete it is ingrained in your head to be tough, to suck it up and play no matter what. As Xavier stated in his interview, “I never wanted to NOT be on the field – I didn’t want to stop playing. I was a guy that if my shoulder comes out of place, if you hit it right the next time it will pop back in…I was that guy. If I lost the use of an arm, I would find a way to get it working again and not say anything.”

One thing I can say, being married to an athlete you will learn a lot about dedication; the definition of when you fall down, dust yourself off get back up and try harder. You will learn that when faced with adversity to come out stronger and swinging harder. You will witness them continuing to play with a sprained ankle, a broken toe, or in Xavier’s case, no toenails every season. You will see them work through pain and soldier through anything that comes their way. You will learn how to be that support for someone when they’ve had a bad loss, when they have had their bell rung a little too hard or had someone step up in their position. These occurrences can bring the strongest person to some of their weakest points.

I remember days after games when Xavier could barely make it down the stairs, he would have to walk down sideways just to get down three stairs. He would take a day or in some cases a half a day to rest and he would be back in the gym. These were the signs I could physically see where the game left its mark. It wasn’t long after we met that his mental health took a downward spiral. I remember speaking to girlfriends who told me “He’s not acting right, you need to get away.” I stood there looking at the man I loved, the man who had the biggest heart of anyone I knew, the man who made me laugh and one of the only people who truly believed I was able to do more. I couldn’t just give up. I knew that the way he was acting wasn’t him, that there had to be more.

I started researching mental health and learning about mental health with athletes, especially how symptoms can be exacerbated when an athlete is concussed. It was scary to read stories of previous players who had suffered concussions and struggled with their mental health. I read about players in their fifties who had symptoms of CTE and it was terrifying to see those symptoms in my partner. It was even scary to try and have “the talk.” I had watched him push through so much physical pain and shut me out from so much mental pain I didn’t know how to talk to him. There were days he wouldn’t leave the bedroom, the blinds would be down, the lights would be out, the TV would be off and all he would do is sleep. He wouldn’t eat, he wouldn’t get up and shower and he would barely say two words to me. My heart was broken. I tried reaching out to people from his past, but they just said, “oh that’s just X.” It was as if he had played this role so well of being “lazy,” of being an introvert, that he masked his depression from the people he loved. It was easier for him to let them think he was lazy rather than let them in on his deep struggle he was fighting on the inside. I knew it was something more. All the signs were there. How was I the only one seeing this? But, it’s true when they say you can’t help someone that doesn’t want to help themselves. I would lay in bed with him and just hug him as he squeezed my hand because he didn’t know how to use his words. We would lay in silence. I knew I had to do more. He was self-medicating and I was worried he was going to hurt himself. It was a terrifying experience to watch someone you love be so close to being gone from this world. I never knew what I was going to come home to. I worried I would come home to a lifeless body and my husband on the ground.

I can’t put into words the emptiness I saw when I looked at him. He would snap for no reason. We would be sitting there one moment having a good time and the next he was someone I didn’t recognize. He became agitated by the smallest thing. From a food order being wrong to me putting something of his in the wrong spot. He would go into a dark place for hours, sometimes days. He would lock himself alone in rooms because he couldn’t control the things he would say. It was like I was looking at my then boyfriend but he wasn’t there. It was someone else in his body. He was emotionless. There were times he couldn’t remember things we had talked about or things we had done. He had difficulty executing plans. It was like he had the map in his head but he would get stuck in the middle. He went through stages where he had no interest in anything, he lost enthusiasm in things we used to enjoy. We would make plans and I would be dressed, ready to go and I would walk into the room to see if he was ready and he would be laying in the dark room telling me to leave him alone. It was painful. There were many times I felt powerless. I didn’t know how to help. I sat there watching the man I love become an empty body. He was emotionless and hopeless. I know he tried at times but it was like he was defeated. That no matter what he did, his depression took over.

What are the tolls on the family of someone suffering from a concussion?

Mental Illness can affect all areas. And when it comes to concussions, existing mental health symptoms are exacerbated by a concussion. It’s a hard concept for some people to accept and it’s a hard concept to try and explain to others. There were times I wanted to reach out to Xavier’s old friends and family members but with the rock bottom he was at I didn’t know how to approach the subject. I had tried for years to help, trying to express my concern, buying books for him to read, talking about our dreams and goals and making a map for us to get there. I always let him know my concern and that I would be by his side when he was ready. We had a lot of good times we talked about where we wanted to be in life but then days happened where he lost all encouragement and drive to do them. Some people I reached out to didn’t understand what he was going through. Xavier was shutting out the world and wouldn’t take calls or invitations to spend time together.

Then he hit rock bottom. It was hard for him to get himself out of bed every day. During the off-season when he was to be working a regular job it never lasted long. It always started out great. He was excited to be working but very quickly he would fall back into depression. He would turn his phone off, doing anything he could to only damage himself more. No matter what I said or did he couldn’t get out of that dark place. It was hard. I was working full time, going to university and trying to keep a healthy environment in our home. Trying to help him took a toll on my own well being. I was losing sleep, failing classes and struggling at work because all I could think about is how badly I wanted to help him. It took a toll on the both of us. Xavier is the light of my life, he is my best friend. That is why it hurt so bad to watch him vanish into a dark place. It was painful to watch him be filled with so much anger and despair. I felt that I had exhausted everything I could do to help.

Xavier was not himself, depression had consumed him. My partner needed help and I didn’t know what to do. I had tried so many times. I tried being nurturing, being tough, tried staying away. At the time, the only thing he could bring himself to do was put the pads on. Football was his escape, but at what cost? Seeing how his depression changed during the season made me think that the constant hits to his head were not helping Xavier’s situation. He was in a helpless state and the only things he felt he had in his corner were football and myself. Every day was a struggle for the both of us. I had to make a decision. I had to give him a choice. It was either get help and I would be by his side or I would have to leave. It wasn’t until that moment and that talk that he decided to get help. It was that same day we sought out assistance. It wasn’t an easy step we took and there was a lot of hurdles we had to overcome as a team. I stood by his side, gave him his space when he needed it but I also had to be that push that wouldn’t let the space he needed become days laying in a dark room. We had to do a lot of self discovery both independently as well as a couple. We started seeing a therapist so we could learn how to be strong for one another. To this day we still see a therapist. There should never be shame in talking to someone. There is always space to become better and stronger. Xavier often tells me I saved him, that he doesn’t know if he would be here If I hadn’t stayed by his side. This is especially hard to hear, it is gut wrenching and crippling to know he was that consumed. It’s difficult to know that no matter how much you love someone and no matter how hard you try that it may not be enough. I am so grateful he made the choice to get help. Therapy was a life saver.

What kind of support did you and Xavier receive?

We had to make a lot of choices to let go of the toxic people and environments in our lives. We had to work daily on getting him out of that dark place. We quit drinking for a year so Xavier could focus on himself with no self medicating. Alcohol and depression is a lethal combination. I wouldn’t say he was ever an alcoholic but it was a deadly virus when he was in his dark place that dragged him down deeper. When you are a spouse of someone who suffers from mental illness – depression and anxiety – it takes a lot of learning on how to be a team. We worked hard to create healthy habits. Xavier was referred to the team doctor who was a great support and helped point him in the right direction to get medication to help balance him. He had frequent visits to a psychologist who helped him to understand his emotions and we started seeing a therapist together.

We didn’t always have support though. There were times he was turned away and told he needed to find help on his own. Being a free agent, without healthcare, and in another country, we would find ourselves in the emergency room.

Support on my end, I had my family. My family has saved me from my breaking point on more occasions then I can count. They are truly incredible people to have supported us in such a lethal time.

Move forward to present day. We are in Chicago and I have had the opportunity to become very close with my in-laws who have also been a great support. I believe it’s very important to have a support system for both you and your partner. It has been a long journey of ups and downs, but we are determined to be strong. Xavier has decided to use his experience to help others and make a difference. It is amazing to see him stand up and share his story. He learned that keeping things in only hurts himself, followed by hurting the people he loves. He is now able to use his voice to let others know they are not alone. This is almost like self-therapy for Xavier. I will never forget the look on his face the first time he stood up to talk publicly about his experience and he received a standing ovation. It brings tears to my eyes every time I think back to it. I think that was the moment he knew it was okay to tell his story and that people cared.

What support do you think should be available to concussed athletes?

I think first and foremost it needs to start with talking about it more – education, discussion, and openness amongst teammates and organizations. Not letting it be the elephant in the room. There should be support groups, therapists and anonymous helplines the athletes can call for help. Over the years, I can think of many times when Xavier should have received more assistance. I am now working with some organizations to create a safe place for athletes. More needs to be done and it starts with someone taking a stand – stay tuned!

How has your experience as an outspoken, supportive wife of a concussed professional football player changed your life?

I have had mixed reactions but anyone who knows me knows that when I feel strongly about something, I will speak up about it. Mental Health – even concussions – aren’t something everyone is comfortable speaking about. I have had spouses come to me with their concerns with their significant others which I am grateful I have been able to point them in the right direction or just be an ear for someone. Mental Health in sports is more common than we are led to believe and by speaking about it we can allow others to know they are not alone. We can provide support. I am thankful for organizations like the Canadian Mental Health Association and Concussion Legacy Foundation Canada who have been very supportive of our mission and look forward to collaborating in the future.

Can you describe what it is like to be part of the support system for a concussed athlete? What advice would you give to others who are support systems for concussed athletes?

I struggled with taking things personal. I would react thinking I did something wrong. I would get angry with the way my husband was acting. My advice is to take time to learn about concussions and mental health. To try not to take it personal. Remember you are a team and always be a friend. Always offer your help and express your concern and never judge or make them feel guilty. They are already hurting enough. You may have to take on more of the work. Seek out a therapist and find help that you can present to him/her. Don’t be afraid to ask “How can I help?” Remember why you fell in love in the first place. Cut out alcohol when times are bad. This can trigger a viral downward spiral.

You also have to take care of our own personal mental health. If you can’t help yourself, you will not be able to help someone else. It can start to break you down so always remember you need a support system too. There will be many ups and some really hard downs that you shouldn’t have to be alone for. For the spouses of football players, Yodanna Johnson and myself have created a private Facebook group called Women of the CFL where we can help you with resources and support. Please feel free to direct message either one of us for more information.