After leaving my hometown and everything I’ve ever known (my family, my friends and my permanent teaching position), this is the second thing that took the most courage to do. My name is Stéphanie Ranger and I’m sharing my story in hopes to raise awareness and shed some light on TBIs (traumatic brain injuries). I am a firm believer in using your voice to share your experiences in order to help others… so here goes nothing!

To begin, a concussion can be life altering and it can turn your entire world upside down. The healing process can be very difficult to deal with mainly because your injury is invisible to the world around you and that can often lead into feeling as if one is exaggerating or faking it. No one should be made to feel that way. Throughout my healing journey, I’ve learned a lot; from life lessons to proper concussion management, and I want to share that information with you. After all, knowledge is power. My hope is that if you or someone you know is going through this, you (or they) can relate and feel more supported. Hopefully someone can learn from my experience. Although my first language is French, I have chosen to write this article in English to reach a broader audience. (À ma communauté francophone, j’ai préservé les extraits en français à l’intérieur de mon article afin d’être authentique et transparente.)

Today, my questions are these:

1. Why am I still recovering from what was initially diagnosed as a mild-concussion 11 months after my injury?

2. Why am I dealing with PCS (post concussion syndrome)?

3. Most importantly, why have I never heard of this and why is my life still affected by it?

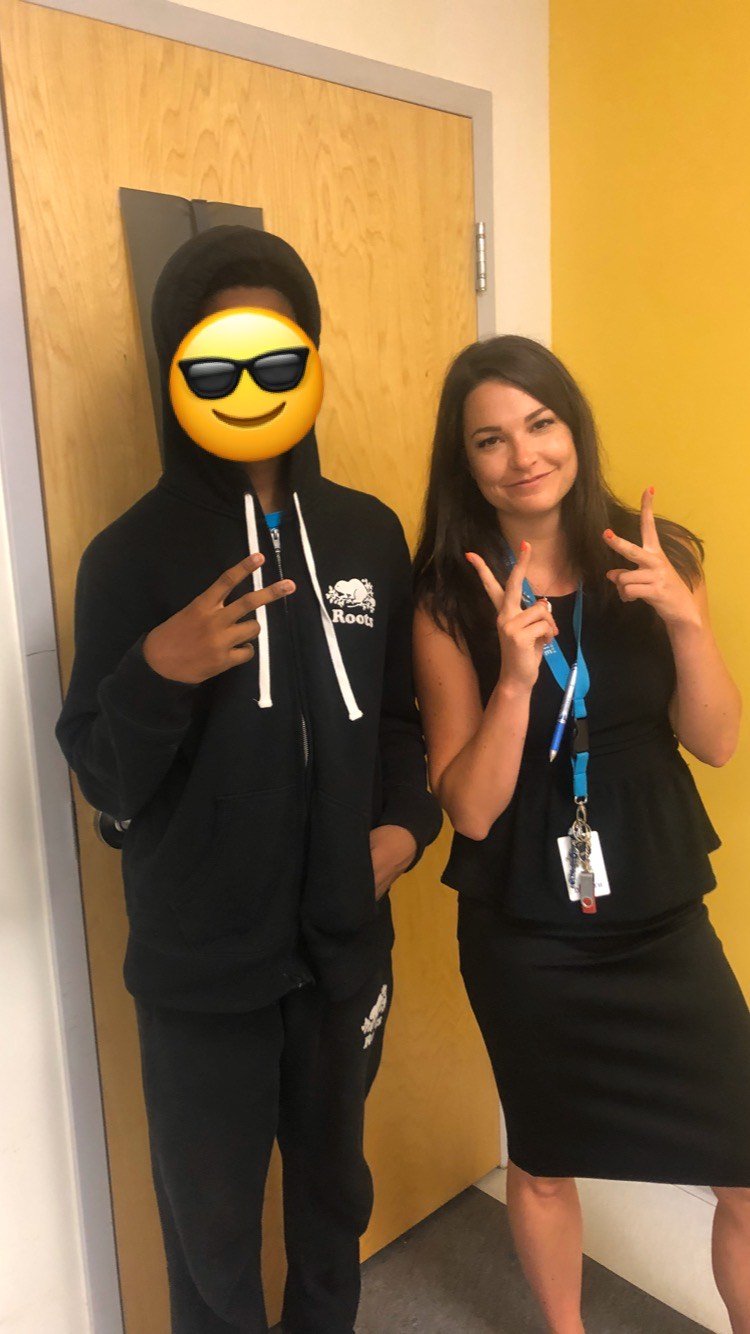

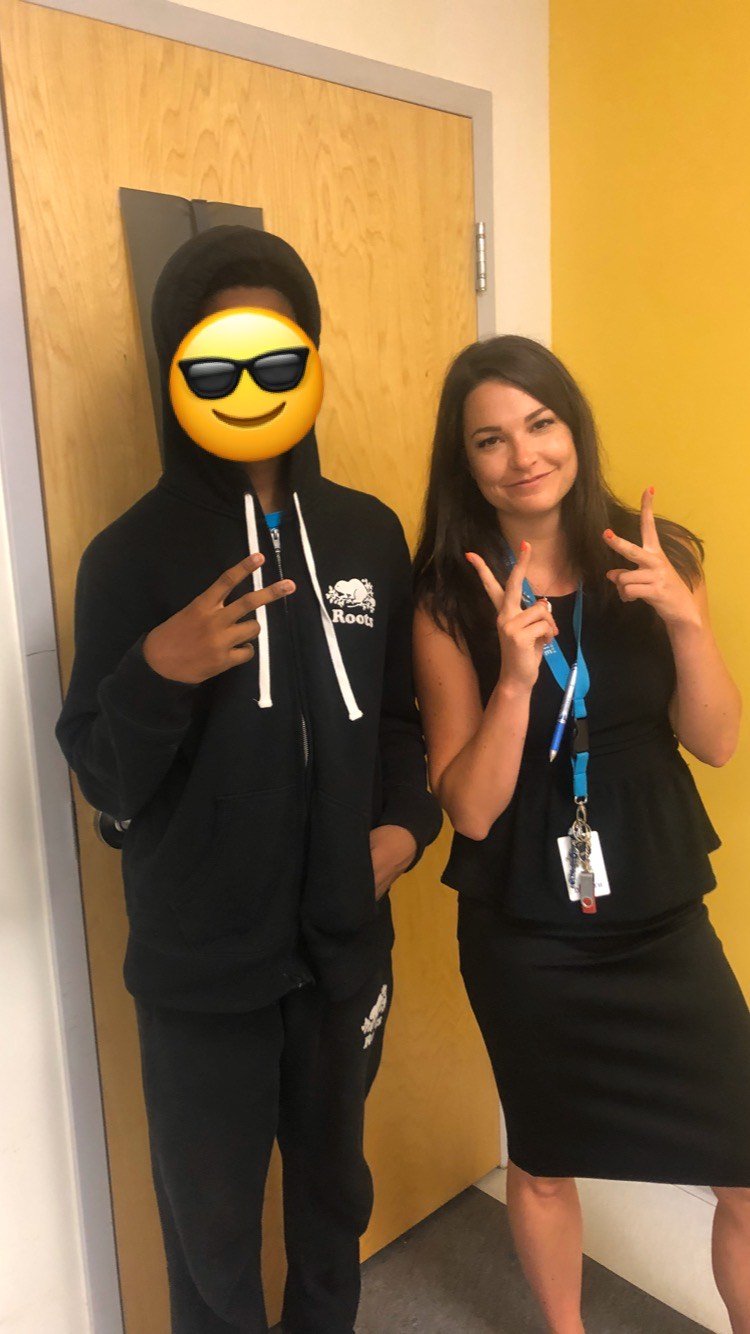

Up until November of 2019, I had a position in a school as a teacher. With the effects of my concussion, I came to the realization that my brain could no longer take the high demands, stress and hectic environment of my job. The symptoms I started experiencing caused me to leave the classroom and find another job that would allow me to simultaneously work and heal at the same time. In my search for a new position, I was blessed to find something in my field. I am now teaching French to adults in a quieter and a more relaxed environment. I am still learning how to go through life with this condition. This includes pacing myself, listening to my body, not overwhelming my schedule and practicing gratitude. Working full-time forces me to sometimes put my social life on the back burner and this can be demoralizing at times but “c’est la vie” (such is life). I know that things could be better but they could also be way worse therefore I am counting my blessings and giving thanks to God and the Universe for the gift of life. I made this decision for the good of my health and I learned this. Often times, we are pushed to make decisions for ourselves, it’s hard but in the end everything somehow shifts in your favour! I learned the importance of allowing your cup to fill before you can fill other’s. You can’t pour from an empty cup.

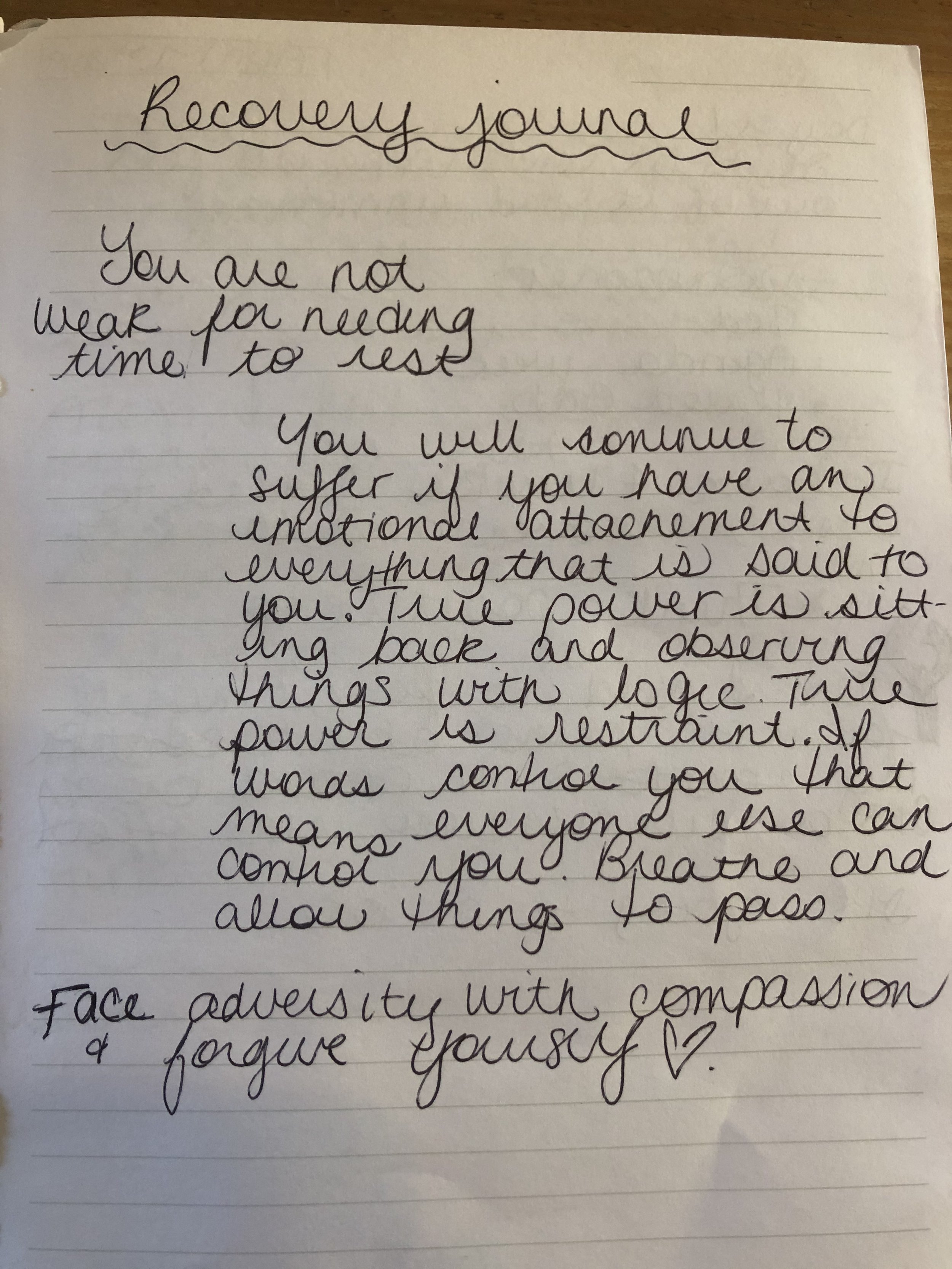

Below is the story of my last concussion recovery, as told by my journal.

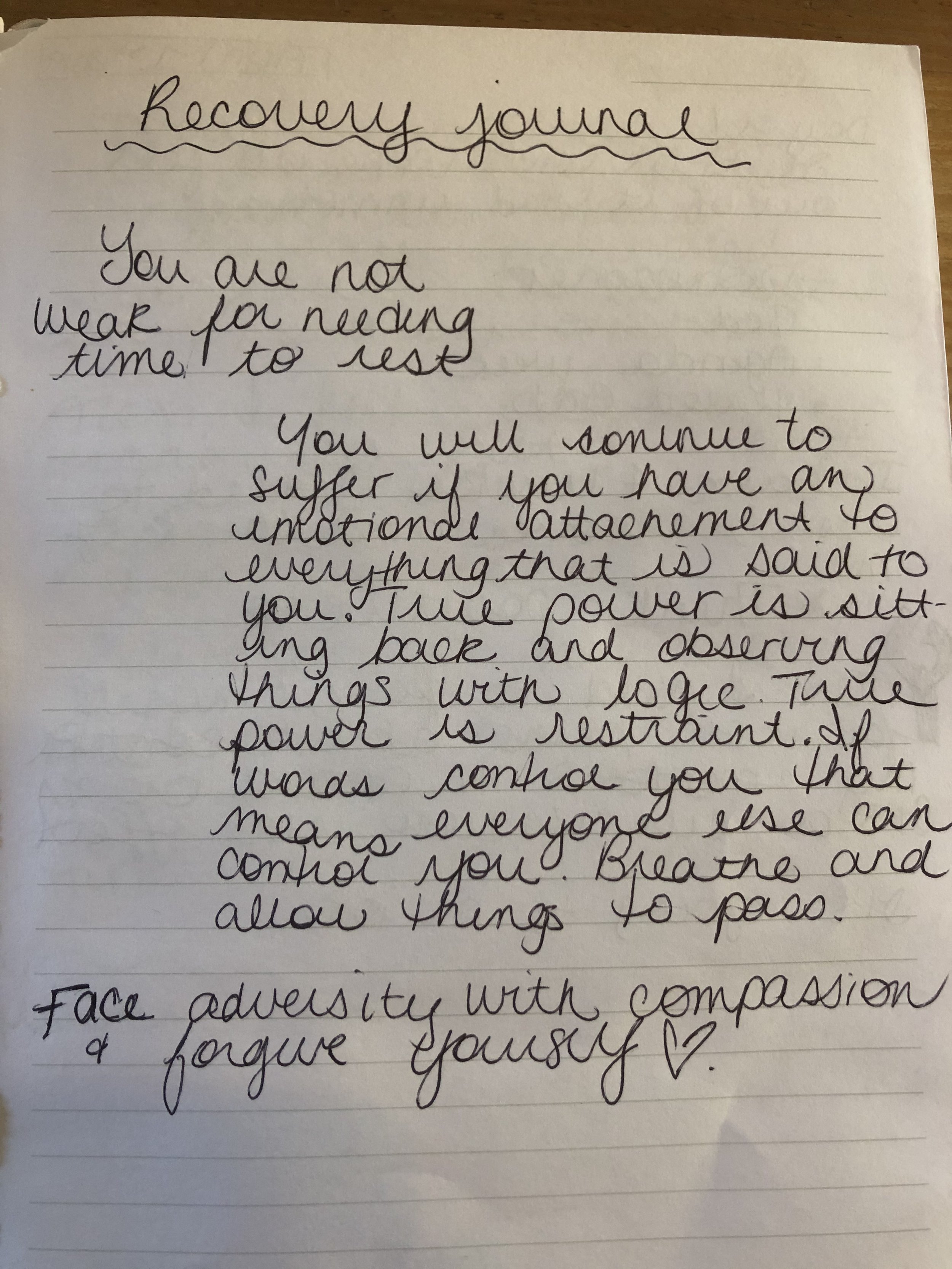

Recovery Journal

“You are not weak for needing time to rest.”

“You will continue to suffer if you have an emotional attachment to everything that is said to you. True power is sitting back and observing things with logic. True power is restraint. If words control you that means everyone else can control you. Breathe and allow things to pass.”

-Unknown

“Face adversity with compassion and forgive yourself.”

I played competitive soccer at a regional level for the majority of my childhood and teenage life. I also played basketball. In saying that, sports have always been a big part of my life. I’ve had a long history of concussions and I always found that it was easy for me to bounce back. From falling backwards into a wall, to hitting my head on the sidewalk, to falling on my head from being on someone’s shoulders at a music festival and ending up in the ambulance, I thought I knew what a concussion was…

My last concussion happened on February 21st, 2019. After accompanying students to our weekly ski trip, I reached underneath the coach bus to get the equipment out and that’s when my head collided with the coach bus compartment door. At first I told people exactly what happened, that I stood up really quickly and that the top of my head crashed into the bottom of the coach bus door which was open and perpendicular to the ground, but after being ridiculed and laughed at by people close to me, I started to change the story to avoid humiliation. I would say that the door simply closed on my head. This way, people understood the extent of my injury and I saved myself the trouble of having to explain what happened when I was already feeling beaten down mentally. It became an automatism and a form of protection for me. The doubts and comments were so hurtful and painful. If you break your leg, it doesn’t matter how you fall but people doubt your head injury by the way you hit your head. It’s sad that I had to tell a semblance of the story to reflect what I knew society would understand and accept. I was sick of being misunderstood, of having to explain myself and being doubted. If you’re reading this article and I told you this semblance of the story, I’m sorry. It was never my intention to deceive you but to protect myself.

After the incident, I went home and immediately went to bed. As soon as my head hit the pillow, the room started to spin and I wanted to throw up. I didn’t lose consciousness or vomit so I went to bed and hoped it would all go away in the morning. The next day, I went to work and I remember being in a fog all day but I couldn’t really put my finger on how I was feeling. I also remember telling a few people what had happened the night before but I wasn’t taking the situation seriously.. After my full day of teaching, I took the airplane to Toronto for a teacher convention. It took a few days for my symptoms to fully set in but I remember having a crushing headache, the room continued to spin, I was more sensitive to light and sound and I was still in a fog. I fought through the whole weekend, trying to convince myself that I was okay. I would take any chance I could, to go into my hotel room to rest. I remember crying. Looking back, I felt that I ultimately let myself down by pushing through the pain and ignoring it…which lead into my next journal entry:

February 27th, 2019

Je me sens tellement stupide! J’aurais pas dû aller à Toronto. J’ai empiré les choses je le sais. Je le regrette tellement. Je me sens comme de la *** et ma tête va exploser et je peux pas penser clairement. J’ai peur parce que je sais pas ce qui se passe. Je me suis jamais sentie comme ça mais tout va être correct. Je vais me reposer cette semaine et je vais être correcte la semaine prochaine.

Translation to English:

I feel so stupid! I shouldn’t have gone to Toronto. I made everything 100 times worse… Major regrets! I feel like **** and my head feels like it’s going to explode and I can’t think straight and I’m scared. I don’t really know what’s going on but it’s going to be okay. I’ll stay home for a week, rest and be good to go by next week!

After having to leave work the following Monday to go see my family physician, my doctor had advised me to stay home for two weeks but as a new teacher at my school, I felt like I had something to prove so I only stayed home for a week. I had a constant headache, my vision became blurry anytime I left my condo, I saw grey cloud particles everywhere, I couldn’t walk for more than 10 minutes, I couldn’t read, couldn’t watch T.V, being in any store made me dizzy and I couldn’t prepare my own food. Taking a shower or brushing my hair felt like the hardest thing in the world. I was completely exhausted. All. The. Time. I sat in my room for more than two days and I spent most of that week off sleeping. After that week, I went back to work. I taught for a week and a half and I was barely surviving my days. Everyday I would have pounding headaches, the pressure in my head was unbearable, I was dizzy and lightheaded, I was still seeing clouds of grey dust in the sky. I spent my prep period in my classroom, lights off, door closed, crying. I would leave work during my lunch hour to go home and sleep (luckily my work was 30 seconds away from my condo). After work, I would go home and take a nap because I couldn’t continue my days. It was awful and I want to apologize to my past self for putting myself through that pain and not putting ME first.

March 6th

Je suis dans ma classe les lumières fermées et je capote. Mon cerveau est enflé et je me sens comme s’il va exploser à l’intérieur de ma tête. Je me sens comme mon front est enflé et comme s’il dépasse de ma tête. Je suis étourdie je me sens comme si je vais tomber dans les pommes. J’ai plein d’anxiété et j’ai peur d’avouer comment je me sens. Je pense ce qui me fait le plus peur c’est d’avouer à moi même et d’être honnête que je ne suis pas OK!

Translation to English:

I’m in my classroom right now with the lights shut and I’m freaking out. My brain feels so swollen and it feels like it’s going to explode inside my head. My forehead is swollen and it feels like it’s sticking out of my head. I’m dizzy and I feel like I’m going to pass out. I’m so anxious and I’m scared to admit how I feel. I think what scares me the most is admitting to myself that I’m not okay.

March break finally came around! As a teacher, the excitement of having a week off to rest my brain and recover was so real. I tried to get out of the house to go shopping with my boyfriend at the time, but had to sit down and take breaks when walking in the mall because I felt like I was going to pass out on the floor or that my head would explode. This was the most frustrating thing. On the way back, I couldn’t drive, I had to shut my eyes for the whole ride. I could not understand what was happening with my body. At the time my best friend was visiting from China so at one point I tried to go out and have a few celebratory drinks with her. Once again, I pushed it and didn’t allow myself to rest. Eventually I had to cancel my plans because the symptoms had gotten to be too much and for some people it was hard for them to understand. They had seen me out the night before so they thought I was faking. I finally dragged myself out of my condo to go to an Alpaca farm and this was the highlight of my week.

March 16th

Aujourd’hui j’ai été à une ferme d’Alpagas. Ces petites bêtes étaient tellement cute et j’étais vraiment heureuse d’être là. Même si je ne peux pas aller nul part, même si je dois annuler sur les party de filles, de familles, je suis reconnaissante pour ce petit moment de bonheur.

Translation to English:

Alpaca farm today!!! These little creatures made me so happy! Even though I can’t go anywhere and I have to bail on all the parties, girl nights, family events, this was the best moment I’ve had in a long time and I am grateful for this little moment of happiness.

At the end of my March break, I started to accept just how badly injured I was. Things were not getting better. As a matter of fact, things were getting worse. I couldn’t stop crying and I couldn’t control my emotions. On top of feeling like this, comments from people telling me to stay positive or to suck it up just made it worse. On the last day of my break, I decided to seek out professional help because I knew I couldn’t go back to work the next day. I called my mom crying and asked her to drive me to the walk-in clinic because I couldn’t drive anymore. Evidently, all the clinics were closed due to it being a Sunday afternoon. I begged the secretary at Apple Tree clinic on Montreal Road to get me in.. I was desperate. After driving around Ottawa to several closed clinics, my mother and I decided to go to the ER.

March 17th

Well on the one hand I completely embarrassed myself today but on the other hand I’m happy I found a doctor that can help me. I showed up to the ER crying and I couldn’t even explain to the nurse how I was feeling. In tears, the only thing that came out of my mouth is “my head”. The nurse looked at me and mumbled… “Okay I’ll just write down mental health.” “No! It’s my head, I hit it. I have a concussion and I’m not okay”.

The doctor gave me two weeks off and told me to stay in the dark for 48 hours. So that’s exactly what I did. All I wanted at this point was to get better, so I committed to following my doctor’s orders. I didn’t leave my room for 48 hours (with bathroom breaks being the exception). I was extremely disciplined. I didn’t check my phone for messages, didn’t answer calls or emails. I didn’t know what was going on. I ended up sleeping for the majority of the time and this is when my thoughts became overwhelming, dark, negative and scary.

March 29th, 2019

I feel so pathetic right now. I feel like I’m trapped inside my body and that this is a sick joke. I feel so depressed and my doctor gave me anti depression medication but I feel misunderstood and people just think that I’m sad. No, like I am depressed man! Today I had to call mom because I was having an anxiety attack and I couldn’t stop crying. Thank god she came over. She did my laundry, made me tea and chilled with me in bed until I stopped crying. I felt like a child stuck inside my adult body. On top of everything, my relationship sucks! The arguments are not good. He’s not understanding that I need a special type of attention to heal. He wants to help but he’s not giving me what I need. I don’t even know what I need. All I know is that I just want him to talk to me on the phone and to come see me. Maybe I’m concussed and not thinking straight. Send help!!

After two weeks off work, I went back. That’s when I really realized the extent and severity of my concussion. On my first day back, I remember completely blanking out in front of my grade 8 students while teaching. I wasn’t just stumbling on words but I was losing my entire train of thought. I couldn’t remember my username or password that I normally enter about 5 times per day (minimum). On top of that, my headache was debilitating, the pressure on the top of my head was excruciating, those grey clouds were back, and I couldn’t focus or walk straight. That’s when my coworker recommended me to go see a man named Asef Rhaman, a specialized concussion physiotherapist at ProPhysio & Sports Medicine Center in Ottawa. I remember the first time I met with Asef I completely broke down. Finally I was able to see someone that was an expert in concussions. He reassured me that everything I was experiencing was real, that I was really injured and that it was going to get better. He put me off work for a month. That was when my healing truly started. I saw Asef and his team 3 times per week for 4 months. I cried so much each time I went to the clinic that there was an ongoing joke going that they would start billing workers compensation for tissue fees. Asef was a blessing. He helped me understand exactly what was happening with my brain and helped me to come to a place where what I was going through was validated.

April 7th, 2019

I slept at mom and pop’s house because I feel so misunderstood by everyone and I don’t know what to do. I feel so out of it this morning. I feel like I have a really bad hangover and like I haven’t slept for days. I’m completely lost, I’m so sad, I’m unmotivated, and I can’t think straight! I don’t want to do today and I don’t want to live anymore. I just want to give up because I feel horrible and nothing is going right! It sounds dramatic but my brain isn’t okay. I’m not okay! I don’t have the energy to do this anymore. I’m depressed and I feel so misunderstood. I feel like my personality completely changed and the joy I have for life is gone. I can’t even take care of myself and empty the dishwasher without wanting to pass out. I’m always in pain.

During the month of April, I decided to be proactive in my recovery and I tried everything. I wanted to get better. As I was learning more about concussions, I realized to what extent I was injured. I knew that I needed way more help than a doctor could provide. I was desperate to find the help and the answers I needed. I had an amazing team of people helping me. I saw Asef 3 times a week, my family doctor, a sports concussion specialist, a neurologist, I tried acupuncture, saw a naturopath, I would regularly go see my psychologist, I even tried Reiki treatments and craniosacral massage therapy. Meetings and appointments had become my life. That’s why when people assumed I didn’t want to get better, it really upset me because no one knew the steps I was taking to heal and to get better.

April 21st, 2019

Why am I not getting better? I’m doing everything right! I’m resting, I don’t go out except for my appointments, I eat well, I drink my water, I take my supplements. I’m starting to feel really hopeless and I’m scared that I wont get any better. Someone save me from myself. I’m sick and tired of not feeling like myself. I want Steph back. I want my life back. It’s been 2 months but I feel like I’ve been dead inside for 2 years. I want to laugh again and really mean it. I want to be able to go outside and take a walk for 15 minutes, I want to be able to go to the store and buy my own groceries. I feel like I’m trapped in my body and like my personality completely changed. I feel so alone and empty. I’m so thankful for my physio team, for my family and friends that understand me. I’m thankful for my brother and his girlfriend that allow me to go over, to nap in their bed when I need a break. I’m thankful for Peanut that cuddled me in their bed when I was napping and crying. I am so grateful for my FaceTime calls with my brother and Peanut.

The hardest part of my recovery was how much it affected each of my relationships. Between spending my energy defending myself and justifying how I felt to people very close to me and fighting with my boyfriend at the time, I learned just how much your relationships can affect your health. The emotional stress caused my symptoms to flare up to the point of my skull feeling like it was going to split open. I am aware that concussions not only affect the victim, but everyone else around. Concussions cause strains on relationships and your change in personality can be really difficult to deal with. For me, my emotional symptoms were crying. Lots and lots of crying. The lack of presence from certain people pushed me to be more independent, and that’s okay. The emotional side of recovery is the most important. Surround yourself with people who help you, believe you and in you. For me, my family and some of my best friends helped me get through my dark times. Going through a breakup and being concussed, I thought it would put me on the floor. I was sad at first, but then I started to heal and this goes to show just how much your emotions can hinder your recovery.

April 28th, 2019

Break up with my bf. I’ve been crying so much for the past months so what’s a little more crying… after the breakup, I felt like some of the pressure in my head disappeared. When I got to church for Andy’s baptism, I cried so much in the parking lot. I was so heartbroken and at the end of my rope. I saw pop and Katia in the parking lot and they just gave me a hug before walking into the baptism. I see this as a symbolism for a new chapter, to heal my heart and my head. I’m so heartbroken, my head feels broken. I don’t ever want to feel like this anymore.

May 8th

Today I woke up angry for being judged and doubted about my return to work. I hate how people don’t believe me and how people don’t trust in my judgement. ENOUGH! I forgive myself for having been a people pleaser my whole life and putting myself last.

I finished the school year with a progressive return to work and only doing administrative work. At first I felt supid, like I was milking my injury but I realized this was in my head (literally). I had a lot of support from my family and my coworkers. Some people will never understand, but it’s not my job to help them get there.

July 15th, 2019

Ok ça fait longtemps que je n’ai pas écrit dans mon journal mais je commence vraiment à prendre connaissance de l’amour de Dieu et de l’univers pour nous, les humains sur la terre. Je commence à me sentir mieux et comme une personne totalement différente. J’ai vraiment amélioré mon mindset et j’en suis fière.

Translation to English:

I haven’t journaled in awhile but I am really starting to understand God and the Universe’s love for us. I’m finally feeling better and I feel like a totally different person. I’ve improved my mindset and I am so proud.

When July came around, I decided to continue to take the necessary steps in order to fully heal. In more ways than only my concussion. In doing that, I decided to leave my hometown of Ottawa to move to another part of the country, that is known for it’s more relaxed lifestyle and laid back attitude. I knew this was exactly what my head needed in order to heal. I knew in my heart that this recovery process was going to be a long one. I was better, yes but I still had more healing to do. A part of me still fears I won’t ever be the same again but this is something I’m learning how to walk through. I don’t know if it’s became a part of my identity; my brain doesn’t work. My attention span isn’t what it used to be. Visually, I still have trouble focusing. I deal with headaches every time I go out in public, when I am surrounded by other people, my brain can’t filter the background noises and all my symptoms come back. The dizziness, nausea, seeing clouds, feeling light headed, light and noise sensitivity and emotional control linked to anxiety are all part of my daily life now. What helps me get through my days is pacing myself, listening to my body and to take a break when I need one. I am still mourning the person I was before my TBI but I am also celebrating a transformation into the person I am meant to be.

When I first moved to Halifax, I started a teaching job and I was teaching grade 1. Within the first month, I suffered from terrible headaches, dizziness, loss of memory and not feeling like myself. I found myself needing to go to bed early, I had difficulty concentrating. I couldn’t eat or have lunch with my coworkers because my head would be too much. Every lunch break, I would sit in my classroom, shut the lights off and focus on my breathing for 30 minutes. Then, I would go out if possible and go for a walk. This kept me going and if I wouldnt follow through with this during my lunch break, I would suffer for the rest of the day, night and week. I pushed it for 2 months until I wasn’t able to function anymore. My symptoms progressively started to worsen until I crashed…again. Eventually I took some time off, tried to go back in the classroom part time and do half days, but the stress of the job and the multitasking was too much for my brain. I decided to leave the classroom and teach in an environment that was more calm and that would allow me to heal.

Going through life and living with PCS is not an easy thing to do. You constantly plan your days and anticipate how your brain will be affected by different settings. What I’ve learned throughout my healing journey is that you are responsible for your healing, and no one will take the initiative to get better like you will. In addition, it is crucial that you reduce your stress levels. I can’t stress this enough… Stress will worsen your symptoms. It’s important to also find people who understand, believe you and support you. I have found my people and I am holding on to everyone that supports me and that is there for me. I love you guys so much (you know who you are). Lastly, the basic human needs are crucial to the functioning of the brain; things such as exercising, sleeping, eating well and drinking water will help you to get through your days. Lastly, it is okay if you need medication to go through your days. If your anxiety or depression is affecting your day to day functioning, please seek help. We are not made to be struggling like this. I take medication for my mental health and I’ve accepted that medication is not equivalent to being weak.

Here are some lessons and takeaways from my experience:

- Setbacks are the most frustrating and discouraging thing but know that they are part of the process and that healing isn’t linear.

- Appreciate the little things

- Be kind. Be kind to others. Be kind to animals. Be kind to yourself.

- Face challenges with adversity

- No job, no sport, no one and nothing is worth your health. Take care of yourself first and you will be able to take care of others

- Healing looks different for everyone

- Know that there is Hope

- Please trust yourself. Only you know how you feel and only you know what you need in order to heal and get back to the person you were before your injury

My life is completely different than it was a year ago and I owe it all to my concussion. Even though it was painful and I still struggle daily with it, my concussion is the best thing that’s ever happened to me. It helped me to completely shift my perspective on life and to focus on the important things. I’ve learned to appreciate life in the moment and to have compassion for myself and others. I used to view slowing down and being sick as a weakness. In the healing process, people have been so kind to me. In a way that has overwhelmed me. My family, my friends, my colleagues and even acquaintances. I have trained my mind to see the good in every situation and to let go of people who don’t lift you up. I’ve learned to listen to my body and to accept the fact that my physical and mental capacity isn’t the same as it was before, and that’s okay. I’ve learned to enjoy every moment fully and trust that things will get better. There is beauty in simplicity and mindfulness. Lastly, I’ve learned that you have good days and bad days but remember, a flower doesn’t grow without rain. Healing isn’t linear and setbacks are part of the process.

My last piece of advice to you. Find yourself a good support system. That is what is going to keep your hope and your faith alive. When I moved to Nova Scotia, I cultivated the relationships that helped me, encouraged me and supported me up to date. My parents, brother, cousins, aunts and uncles in Ottawa as well as my lovely friends, you guys have a special place in my heart and I am lucky to have such special people in my life. In Halifax, I was blessed to have the support of my uncle and my aunt. They took me in like their own daughter. I couldn’t have done it without their help and for that, I am so grateful. Furthermore, in my search for community, I have come across such wonderful and kind people. From new friendships and coworkers, to a wonderful church community that has given me hope. Thank you Pastor Mike and Nova Church. My relationships have allowed me to walk through my healing process feeling loved and encouraged. Lastly, after a few visits to different concussion specialists and physiotherapists in Halifax, I recently met with Dr. Rebecca Wynn, a chiropractor. As soon as we started talking, a wave of hope filled up my whole entire body. She explained to me what was happening in a way that no one else has. She ran a few tests on me and immediately noticed a problem with my left eye. She also covered different aspects of a concussion. I can’t wait to start my treatment with her!

In conclusion, don’t sweat the small stuff and never give up on yourself. I promise that you will see yourself transform from victim to victor. On lâche pas!

Stéphanie Ranger