Stephen is an award-winning, forward-thinking and progressive employment lawyer. He is a 2013 graduate of the University of Alberta Faculty of Law in Edmonton, AB. Stephen champions human rights, equality and justice and has focused his attention on being a brain injury advocate and agent of change. As a survivor of repeated head trauma, brain injury and ongoing post-concussion syndrome, Stephen’s goal is to facilitate increased awareness to these troubling and often misunderstood issues, particularly within the area of employment; one of the most fundamental aspects of life, and most concerning issues for those affected by concussion and post-concussion syndrome.

As I write this, I am feeling tired, beaten, worn out and fatigued – mentally, physically, and emotionally. My life’s journey has been a long and troubling battle with head injuries, depression, anxiety, exhaustion, substance abuse, self-loathing and mistreatment by my profession. 90% of the time, I can hardly function in my day-to-day life, as I deal with extreme migraine headaches, profound body pain, incapacitating fatigue, severe depression, sensitivity to noise and light, you name it – I can check all the boxes. I have problems with memory, impulse control, mood imbalance, cognition and executive functioning. I have been seen by every type of physician and medical professional there is; from neurologists, endocrinologists, psychiatrists, physiatrists, somnologists (i.e. sleep doctors), etc. Every answer has been the same: my brain has been irreparably injured by way of repeated blows to the head. I do not have cancer, a stroke, ALS, etc. I have a brain injury. A serious and likely progressive medical condition.

I’m no longer ashamed to admit that I have frequently contemplated and likely subconsciously attempted suicide on more than one occasion over the years. When nobody would be on the highway at 3 a.m., I would do this through driving recklessly at high rates of speed while very intoxicated (although, I am now four years sober) – hoping, just hoping that I would lose control, crash and have the pain instantly taken from me in a single fatality accident. I have screamed out for help for over seven years, more often than not being completely ignored, including by members of my own family and community. At times, I was told by my family to keep quiet and not reveal such private information, likely because it would have the practical effect of embarrassing them. In large part, I have kept quiet about my chronic pain and suffering, which is largely due to the stigmatization still unfortunately ascribed to those dealing with mental illness, whether occasioned by traumatic brain injuries (“TBIs”) or not. This is especially so in my profession as a lawyer, an archaic profession that still generally refers to these symptoms as “mental break-down” and will not hesitate to demonize you for such in what is brazen discrimination.

In opening-up and airing my story publicly, I am attempting to effect change and promote awareness of these troubling issues, particularly as they relate to survivors’ employment – concussion, TBI and Post-Concussion Syndrome (“PCS”) are very real, and society can no longer turn a blind eye to it. It is a crisis affecting athletes, first responders, law enforcement, military veterans and every-day people. I want to be heard and talking about my journey is a large part of the healing process. We can thank Hollywood for creating some minor and fleeting attention to the issue through, among other things, the 2015 film Concussion starring Will Smith; but there is still much more work and advocacy needed to be done, particularly on a day-to-day, grass-roots level. The level of general awareness and understanding of the intricacies involved in concussion, TBI and PCS is shockingly and concerningly minimal. While my story is seemingly more negative and dark in tone than others, it is not intended as such. It is intended to illustrate the real-life effects of this miserable and sinister condition with a view to fostering greater awareness in the community and among employers – principally so nobody else has to go through it. The ugly truth of concussion, TBI and PCS needs to be exposed, but I will do my best to illustrate the silver lining at the end. What follows is my raw and uncensored story.

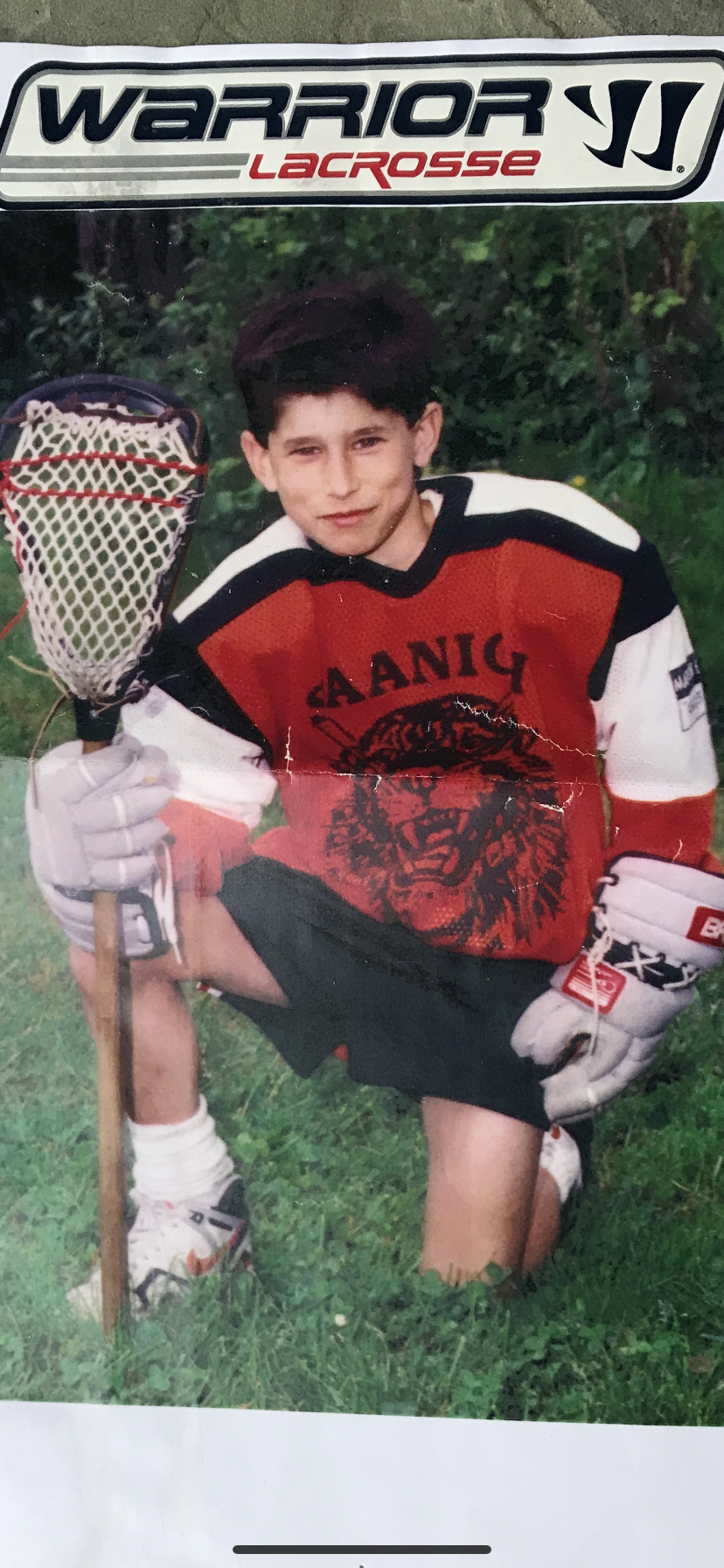

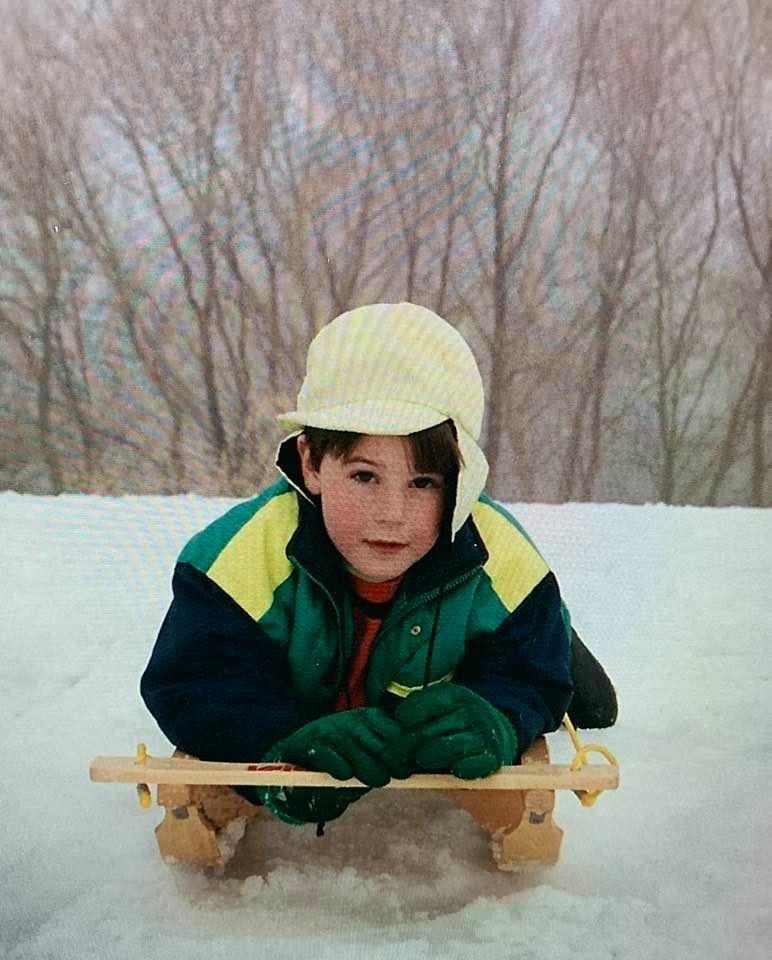

I was a happy and energetic child. Looking back, as a youngster, my passion for life and high-energy caused me to hit my head a lot, seemingly far more than other young boys at my age. The many scars all over my head remind me of all the fun (and trouble) I got into as a child. Whether it was throwing rocks with my cousins, running through hallways at school or playing sports with my friends, my head took the brunt of many inadvertent hits; 25+ years later, the many scars from sutures and lacerations to my head offer evidence of what was a rambunctious, happy and fun-filled childhood. Boys will be boys, right?! What we thought was a young boy’s zest for life ultimately laid the groundwork for what was to come.

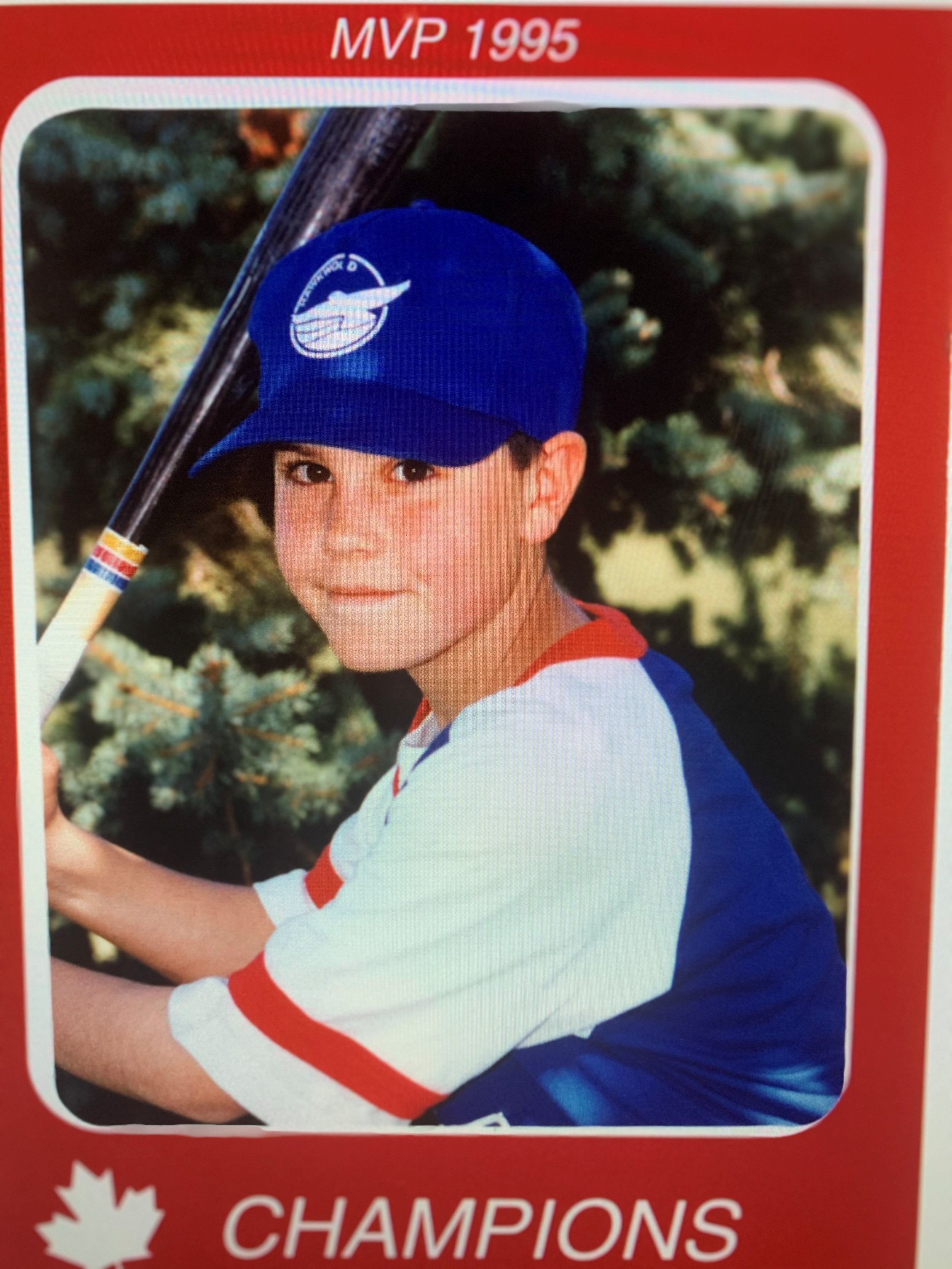

My love for sports began at an early age and it wasn’t too long before I was playing football and baseball at a high level. I was an athletic kid and was blessed with the natural skillset and physique to excel. I was big, tall and fast relative to the other kids, and had “good hands”. The gift of genetics blessed me with big and muscular legs, which enabled me to run fast. In football, I was a wide receiver and kick returner. I loved to run, and run fast. Dodging, tiptoeing around and outmaneuvering my foes on the field was awesome, and so was laying out to make that catch – “did he actually just grab that?!” was something I commonly heard. In baseball, I was a centre fielder. Here, too, my speed, hands and agility enabled me to make that diving catch on-the-run after tracking down a ball a hundred feet away that nobody else could catch-up to. And, man – did I ever have a notorious cannon for an arm, gunning out my competitors at home plate from deep in centre field, without so much as a single hop. After a while, other players just stopped running and testing me, knowing I would get to that ball. I was also a constant threat on the base paths, quite literally turning what would otherwise be a single into a triple at almost every opportunity and I don’t think I ever failed to steal second and third base, more often than not leading with my head.

Unfortunately, my on-field skills and passion to do the unthinkable caused me to time, and time again, hit my head. Whether it was taking the huge hit to dive into the end zone headfirst, laying out to make a catch that I knew would hurt with an inevitable helmet on helmet hit, running into an outfield wall at full speed to make the unimaginable grab or taking a knee to the face while sliding into second to advance the runner, my head (my poor head) was repeatedly battered. As an adolescent and young adult, I still didn’t think about the consequences of what I was doing; at that time in the late 1990s and early 2000s, neither did my coaches. I recall one specific instance at high school football practice where I took a vicious helmet on helmet hit, waking up after a few seconds covered in my own snot. Dazed, confused and disoriented, I got up, wiped off my face and got right back out there with my coach’s blessing. What we all thought was a normal football play was no doubt a concussion, one of hundreds of undocumented TBI’s I have likely sustained. We just shrugged these things off; it was all part of the game, something that would happen again and again, that my parents didn’t even know about. In the end, I was always that guy, unafraid to dive head-first to come up with the spectacular. People loved me for it.

Around the age of 20, I gave up on competitive athletics after having reached the college level to refocus on my academics. Although I had exited the world of competitive sport, and as I now know it, much damage had been done that was carried forward with me into the next chapter of my life.

I have always detested bullies and rude, inconsiderate people – I continue to dislike them to this day. As a bigger-than-average teenager and young man, my strong passion for justice and helping others also contributed to my taking on what was in a sense a “protector” role, whether on or off the field. I am 6’ 2” and 240 pounds, but a total softie on the inside (the real me). Unfortunately, I often found myself involved in physical altercations and skirmishes that had initially involved others being mistreated in some sense and ended up with my coming to their rescue or defence more frequently than I probably should have. I can’t even begin to count or remotely ascertain how many punches I had needlessly taken to the head over the years in this regard – here, too, my parents were largely unaware. All I have left are the physical scars to show for them, and the internal damage to my brain tissue. I recall one specific instance when I stepped in to intervene in a situation involving a young woman who was being sexually harassed by a group of men at a night club. I was ultimately beaten, punched and kicked repeatedly by four to five guys, but by doing so, I saved a young woman from being harassed, degraded and humiliated, and she was profusely thankful. I would do it again in a second.

Good intentions aside, I believe the increased frequency of these instances throughout my 20s can be traced back to behavioural issues associated with physical changes in my brain that were attributable to all of the recurring head injuries. I struggled to control my impulses and had less inhibitions, at times when I should have been more controlled. I have no doubt that this was because of the head injuries. Emotional regulation and impulse control problems are sure signs of this and there was no other likely cause for the changes. Contrary to what I was being told, I was not simply looking for attention. Nor was I just a bad guy who liked to fight. I was a young man with a brain injury in need of help.

It was around this time that I first began to notice signs of depression. At 16 and 17 years of age, nobody really knew what was wrong. I saw my family doctor and was given a standard antidepressant to help with, what I was told, was normal adolescent imbalance. The medications helped for a little while but it wasn’t long before I discontinued using them entirely; cold turkey. In my view, and together with the behavioural issues, aggression (however well intended) and impulse control issues, these were the subtle signs of something more sinister beginning to take hold. The subtle indicators of TBI and PCS were easy to miss and mischaracterize as a common teenage imbalance, and I blame nobody – but I now know this is when the snowball effect began. Serious changes were taking place inside my brain… and in the early 2000s, who really knew?

I was always a smart kid. I consistently scored well on achievement exams and intelligence was never in question; every teacher knew I had some kind of gift for articulate communication and advocacy. What was in question was my motivation and effort. After a while, I just stopped trying. My parents were mad at me and sought to discipline me for it and, so, too, did my teachers and school administrators – I didn’t even care. Keeping a kid in detention or suspending him for not trying hard enough obviously was not the answer. That was entirely misplaced. Again, looking back, I now know this is when the snowball effect of concussion and TBI took root in my brain; everything pointed in that direction. In time, I acceded to the demands of my family and requests of my teachers to start trying in school. I did just that, ultimately graduating magna cum laude from a national university with my degree, achieving a near perfect GPA.

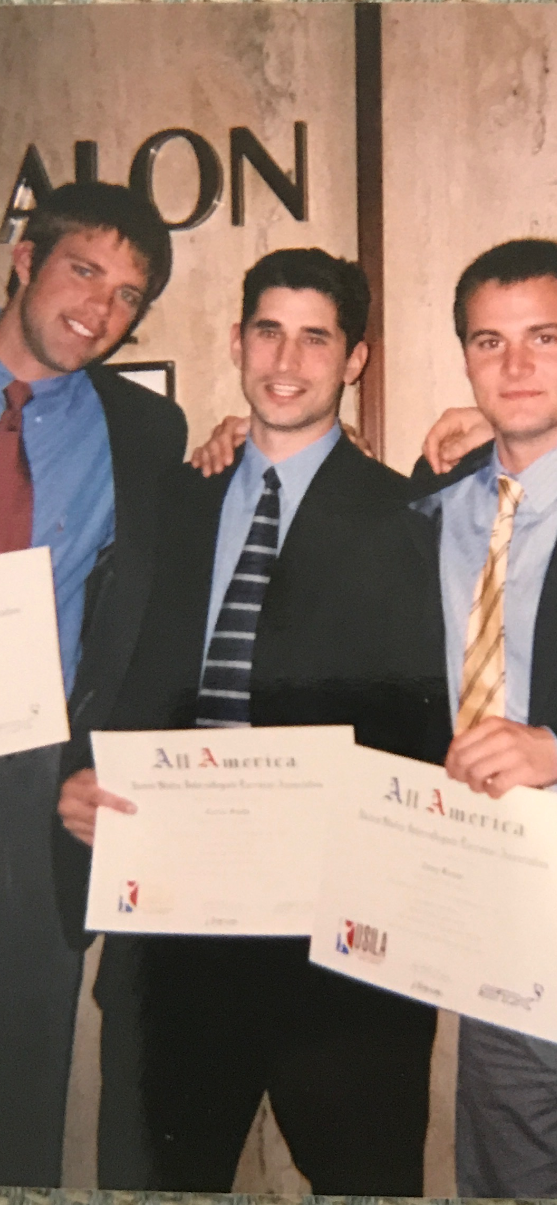

However, my problems continued. Impulsive behaviour, irritability, mood imbalance, anger, depression – the list goes on. I was assessed, and assessed again. “No, you’re not bipolar” and “no, this is not a personality disorder” is what I uniformly heard from doctors. Despite these ongoing struggles, my passion for justice and helping others continued. I would not be deterred. I eventually landed at a top Canadian law school where I again excelled academically. I was well-known by my peers and law school faculty alike for skilled communication, articulate advocacy and a tenacious commitment to fighting for what’s right. “He is a bright, ambitious and articulate person, and he is certain to become a distinguished graduate of any law school he attends” is what one law school professor (now a judge) said of me. My commitment to excellence and proven achievement led to me being recruited by almost every major national law firm in Canada. Given my ongoing symptoms, it was not always easy but I managed. This all changed during what was my final semester of law school – only one month away from law school graduation.

In March 2013, I attended a law school mixer at a local bar. It was a well-attended event by law and medical students and by all accounts, a fun night. That is, until the end of the night when a group of unidentified men (neither law nor medical students) attended the private event and were removed for harassing a group of female law students. I was alerted to this by the female law students and exchanged words with this group of men. The group of unidentified men were successfully removed from the premises. As we were exiting the establishment later in the evening, I was attacked from behind and thrown into a cement wall. I have no recollection of this and my understanding is based entirely on what I was told by witnesses. I was knocked unconscious and awoke disoriented in a pool of blood with a severe laceration to my head. I was trying to stand-up and move but my arms and legs were not responding. I was scooped-up off of the ground by the establishment’s staff and immediately taken to a hospital. My head was stitched-up and a CT scan revealed no skull fracture or internal bleeding. Still disoriented, I was discharged and sent home alone. Since that time almost eight years ago, I have never been the same.

In the weeks and months that followed, I began drinking heavily. On the advice of my physicians, my start-date with a large national law firm where I’d be completing my articles (i.e. lawyer licensing process) as a Student-at-Law was delayed because of how I was feeling. I was scheduled to start in June 2013 and my start had to be rescheduled to August 2013. This instantly created tension with my new law firm, who looked at me and because I appeared to be fine on the surface, didn’t believe a single word I was saying – even with the medical confirmation in hand. “Concussion?”, “didn’t you recover from that bump on your head in April?”, they would ask. They just didn’t care to understand. Nevertheless, I was expected to work 60-80 hour work weeks, be “on call” at all hours and make myself available on a moment’s notice. My medical condition didn’t supersede this “rite of passage” or otherwise justify any accommodation in what is the “old boys’ club” of the archaic legal profession. It wasn’t long before I couldn’t keep-up with such rigorous demands. In a profession like law where your worth is determined solely on the basis of how many hours you bill, and how much revenue you generate for the firm, I was cast aside and alienated from my cohorts. I was placed in a small office in an entirely different building location and essentially left to rot in silence. Senior members of the firm had been circulating an email about me with funny memes attached, poking fun at me for being a “drunk”. This was something that had been happening for months, unbeknownst to me until another lawyer drew it to my attention. These were people responsible for my legal training, people I trusted. It was unconscionable.

The firm’s Student Committee told me that I wasn’t liked by the Partners and therefore would not be welcomed back upon the conclusion of my 12-month articles. According to the Partners, I was not permitted to refuse requests for assistance at 9 p.m. on a Friday evening, or at 7 a.m. on a Saturday morning, regardless of how I was feeling medically. To do so made me a non-conforming, “wrong fit” for the firm. In reality, I know I was cast aside because the firm didn’t see enough opportunity for revenue generation with their investment in me because of my PCS and restricted working capacity relative to others, which was only being made worse by the absurd constraints placed upon me. And I know this because I received several very strong references from senior and well-respected Partners of the firm, despite what the Student Committee was saying to me. I was shattered. Everything I had worked so hard for was gone, just like that, and all because of PCS, a medical condition that they doubted and did not recognize. Had my medical condition been cancer, or something else the firm could have capitalized on from a public relations perspective, I’m certain the treatment received from my firm would have been different. But concussion and PCS? Nah, there’s no goodwill or marketing opportunity in that, they thought. I was just dead weight and some kid dealing with depression to them. That’s just plain wrong, any way you look at it.

I moved to a new employer after being called to the bar in September 2014. I still had problematic symptoms associated with PCS in connection with the March 2013 TBI, but the change in environment was positive. I had more flexibility in my work schedule, more supports and an increased work-life balance. I was starting to feel better. All of this progression came to a screeching halt only a few short months later, when I was involved in a serious car accident in November 2014. On my way to the gym one night, completely sober but extremely fatigued, I went through a red light at an intersection and collided head-on with another vehicle at a reasonably high rate of speed. I am ashamed, and it’s not something I generally talk about, but it appears as though I was at fault. I do not remember the car accident and my understanding of it is based only on the recollections of witnesses and dashcam video footage from the other driver. That poor driver – I have much guilt and shame about it. Fortunately, the other driver was generally okay but my heart still aches. As for me, yep – another serious concussion, only 17-months after the last serious head injury, and just as I was starting to feel somewhat well again. My vehicle was a total write off, my head slamming violently from left to right, front and back. I finally came to a stop some distance away, completely turned around and on a sidewalk. My PCS had been causing me to feel very fatigued, but I pushed myself to go to the gym that evening after work, around 7 p.m. – I shouldn’t have done this, it was a mistake. Disoriented and confused, I was pulled out of the vehicle by a concerned passerby. PCS had come back to bite me again.

Based upon the previous mistreatment of me, I wouldn’t let myself fall victim to that discrimination again. I immediately tried returning to work after a couple of days, but it wasn’t working. I couldn’t think straight or concentrate and was overwhelmed with migraine headaches – I was fumbling words, unfocused and beyond exhausted. I was mad at the world… man, was I mad. I started drinking excessively the night after the accident to numb the pain, but it wasn’t working. I went and saw my doctor who immediately recommended time off from work. Given my longstanding history with head injuries, I was now worried about my future, my employment prospects and my wellbeing. I had almost $100,000 in student debt to pay off from law school, I couldn’t just stop working, right? I had fallen into an even deeper depression, and my love affair with alcohol blossomed into a full-blown addiction. Over the next three months, I went through an occupational rehabilitation program, designed to help me heal and return to work. That helped only minimally and after three months of short-term disability, I was feeling pressure from work. I returned to work on a graduated basis in April 2015, starting with half days. My father was urging me to get back to work as quickly as I could – to him, my employment prospects were bleaker the longer I was away, injury or not.

My superior thought I was abusing the system and didn’t believe I had a bona fide medical condition. He would make public comments like “I mean, it was just a little bump on the head, right?”, “are you enjoying those half workdays?”, etc. It was extremely uncomfortable – talking to Human Resources about it resolved nothing. It’s like he was deliberately trying to push my buttons, knowing I was recovering from a serious head injury. At one point, this guy even engaged me in a full-blown shouting match in my office, where he explicitly questioned my aptitude.

In the end, as soon as my job protected medical leave concluded, I was terminated immediately in September 2015. By this time, my PCS was in overdrive. I was still labouring from the effects of the November 2014 car crash when, once again, my employment was stolen from me in what we can reasonably infer was because of my medical state.

Fast forward to 2017 – the employment law firm I had retained in 2015 to sue my former employer for wrongful dismissal and discrimination subsequently hired me as its senior employment law associate after it was impressed with my knowledge and passion for employment law. Obviously, having been my lawyers, they were intimately familiar with my medical condition and PCS. In fact, we had successfully settled the case against my former employer on this basis. Knowing of my PCS, the firm had agreed, time and time again, to provide me with short-term disability benefits in the foreseeable event that my PCS ever required me to take another medical leave – a promise that was never honoured. By September 2017, I had already been to a residential inpatient treatment centre for substance abuse after an unsuccessful attempt to drink myself to death on December 31, 2016. Feeling better in my newfound sobriety, I had now been diagnosed by my endocrinologist with an irreparable injury to my pituitary gland. According to my endocrinologist, my brain had been so badly battered and tossed around over the years, all the blunt force trauma caused my pituitary gland to stop functioning. Because of this, the combined effect of my PCS, demanding working hours and associated stress as a busy lawyer, and my body’s lack of naturally produced growth hormone (not in the sense of “body builders”, but that which is necessary for basic bodily functioning) caused me to tank and run right into the ground. I had to take another medical leave of absence as the cumulative effect of all of this had caused me to become completely burned out – I would now be starting a new medication. This time, however, I would have to do so on an unpaid basis as my employment law employer reneged on its promise to provide short-term disability coverage – the irony that a group of employment lawyers would so severely marginalize its employees. In any event, I didn’t previously know that repeated head trauma could damage the pituitary gland and cause it to stop working, resulting in a growth hormone deficiency and making the effects of PCS even worse. I am very thankful for the skill, care and attention to detail I received from my endocrinology team in Calgary.

After generating hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue for the two owners of my law firm, I was left with nothing – no support at all. I resigned my employment, started my new medication and tried to rehabilitate myself. I was alone and completely cut off from the world, having then only recently ended a long-term relationship in large part, due to problems associated with my PCS. With no income and no insurance (and not even the basic statutory minimum entitlements all employees are entitled to by law in Alberta), I started to default on everything and could not afford to live. But for the emergency financial assistance from my family, I would have been homeless and unable to provide for myself. Once again, suicide was looking like a really good option and I came close to taking the next step, had it not been for some good friends in my circle of sobriety. My credit rating dropped by over 300 points from what was an unblemished and long credit history because of this, and it has never fully recovered. To this day, I still cannot obtain even the most basic financing or credit.

Ten months of unpaid medical leave, being ignored by my professional association with my genuine concerns of mistreatment by my law firm employer, multiple credit defaults, near bankruptcy and an obliterated credit rating later, I had to start earning an income. By this time, I had met my now spouse, and love of my life, who understood me and gave me the support and motivation I needed to get back out there. I had built-up a strong reputation for being a client-focused lawyer and employee advocate and had developed a loyal client base. As a justice oriented, relatable and down-to-earth guy, I resonated with the public. I took it upon myself to start my own employment law firm, with a particular emphasis on assisting employees only – a large undertaking for anybody let alone somebody with serious PCS and a pituitary gland injury, but I was ambitious. From the get-go I faced an uphill battle with my professional association.

The professional association requested sensitive medical documentation and subjected me to questionings, assessments and the like, impliedly assuming I was unfit to practice law because of my PCS and pituitary gland injury, a medical condition it didn’t understand, and did not want to understand. It was clear that this archaic and outdated legal profession was incorrectly referring to PCS as a “mental break-down” (as if it were still the 1970s) and stigmatized me because of it. I really do hate that term and think its use is reflective of a complete unwillingness to understand what PCS really is; a brain injury. I was subjected to a clear double-standard throughout the administrative approval process and felt completely marginalized and discriminated against. By this time, I had also just found out that my spouse and I were pregnant with our first child – I knew I had to act fast in creating something to provide for them, not knowing exactly what the future had in store for my health. That was of real concern.

Over the next 2.5 years, between 2018 and 2020, I was relentlessly targeted, harassed and discriminated against by my profession and a select handful of rogue people in the professional association in particular. This included the time my spouse and I were in the NICU with our son who was clinging to life. It just never stopped. I spoke out against my mistreatment by the privileged few who run Alberta’s legal profession, expressed that the mistreatment of me was making my PCS worse and things only intensified because of it. The professional association and my legal profession cast me aside and wrote me off as being “crazy” or a “bad apple”, however misplaced that actually was. These folks were referring to medical documentation from my comprehensive team of doctors specialized in concussion and brain injury as “insufficient”. This was beyond disheartening. Not only was there never a single accommodation made, the professional association took it a step further and engaged in a deliberate scheme to exacerbate my PCS and pituitary injury and run my health right into the ground. My human rights were not only disregarded, they were brazenly violated. In the end, and after graduating from law school at the top of my class, my career, livelihood and ability to provide for my young family has been stolen from me – not because I did anything wrong, but because I have a brain injury that was unrecognized and laughed at. The successful business I created was egregiously taken from me in bad faith by a group of bullies who didn’t believe PCS was a legitimate medical condition.

As a result of the 2+ year campaign of mistreatment and discrimination, my PCS has significantly worsened. At times, it is difficult to function in even the most basic of ways. Among other things, I am angry and react impulsively. I am a lightning rod for angry outbursts, for which I have been prescribed an anti-seizure medication to help stabilize it; however, it has zombielike side effects. I do not want to live that way. Of concern, I now have numerous brain lesions in the frontal lobes of my brain that were not previously present. Of course, my physicians reasonably infer this is a progression of my brain injury, due to the extreme and sustained stress I have been labouring under over the past 2+ years which has irreparably aggravated my condition. This all could have been prevented if PCS and its debilitating effects had been understood and recognized by the professional association. I now believe I am suffering from the deleterious effects of CTE, and that is a very scary thought. Not only was my career taken, what was left of my health has been stolen from my family, spouse and children. I’m nevertheless proud to have pledged my brain to UNITE Brain Bank (formerly VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank) to help further the research into concussion and CTE, once my time is up.

I do not know what the future has in store for me. I do not know if I will ever again be able to provide for my family (we also just welcomed a second child amidst this chaos), something I worked so hard to do despite my PCS. I do know that I want to be an agent of change. My PCS aside, I have a gift for communication and leadership – that has never wavered. Perhaps my calling in life is now to increase awareness of the troubling and sinister effects of concussion, TBI and PCS. If nothing else, to ensure no other individual afflicted with these conditions is so brazenly harmed by a professional association (or employer) that fails to recognize PCS and TBI as a valid medical condition. I will be that advocate for change.

Since going public with my story, I have received a lot of support… I guess my point is, don’t let anyone tell you to be quiet – silence helps no one. Talk about your problems and don’t be afraid or ashamed like I was, for far too long. We all lose when these things aren’t talked about. The silver lining in all of this? People are starting to understand my story and what it’s been like – those misperceptions of PCS and brain injury are changing in real time. The positive energy associated with that validation and support from the public is immeasurable. Remember, we aren’t helped unless we ask for it. PCS is all too real. It’s time society recognized it in a manner no different than cancer – let’s change that perception by working together to foster understanding, empathy and awareness. It’s never too late. We’re in this together.