Posted: June 9, 2020

Episode 1: Hello!

Episode 2: Mindset

Episode 3: Noise & Light Sensitivity

Episode 4: Staying Social

Episode 5: Coping with Loss

Episode 6: Sleep Issues

Episode 7: Exercise

Episode 8: Vision

Posted: June 9, 2020

Episode 1: Hello!

Episode 2: Mindset

Episode 3: Noise & Light Sensitivity

Episode 4: Staying Social

Episode 5: Coping with Loss

Episode 6: Sleep Issues

Episode 7: Exercise

Episode 8: Vision

Posted: May 11, 2020

Alan Blyweiss started boxing in 1976 as a seven-year-old in the Baltimore/D.C. area. He was 88-12 as an amateur. His amateur career included a fight against former heavyweight champ Tommy Morrison to a four-round loss that turned into a blood bath. Growing up where he did, he was able to spar up-and-comers like Hasim Rahman, Riddick Bowe, and Mike Tyson. At 20-years-old, he was told he shouldn’t box anymore due to a spinal disc fusion. His professional career was over after just two fights. Nicknamed “The Rock,” Blyweiss became a sparring partner for some of the biggest names in boxing like Vincent Bolware, Lennox Lewis, Terry Ray, and Larry Holmes. Without much of an education, Blyweiss felt his only means were to be the punching bags for some of the most powerful punchers in the world.

A life in boxing left a toll on Blyweiss’ body and brain. He has had his spine caged, complete elbow reconstruction on his left arm, Tommy John on his right elbow, numerous hand surgeries, broken noses, and procedures to remove cartilage. He also sustained numerous concussions and blackouts in sparring sessions.

Blyweiss felt for a long time that something was wrong with his brain. He exhibited behaviors and personality changes that alarmed his wife and children. He lost control of his inhibitions, suffered from confusion, had bouts of rage, and severely lowered executive functioning abilities. Doctor after doctor couldn’t give him an answer for his issues until a 2017 visit to Johns Hopkins University. There, doctors told Alan they suspect he lives with what was used to be called “punch drunk” syndrome, and what we now know as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Living with suspected CTE has placed a tremendous burden on Blyweiss’ family. His wife had previous experience as a caregiver for dementia patients and now supports Blyweiss in his daily bout against the symptoms of the degenerative brain disease. Despite everything, Blyweiss’ fighting instinct still persists. To combat his suspected CTE, Blyweiss turned to poetry.

He writes whenever inspiration strikes with the purpose of compiling a set of poems to share with other patients and families affected by CTE.

“There is no schedule with my disease,” Blyweiss said. “Every day is a new adventure. But I’ll keep on trying and never give up.”

See below for a collection of Alan Blyweiss’ many poems. You can connect with him at [email protected].

CTE Warriors

Man hands hurt so bad from all the years of fighting, have to get through it so I can keep writing.

This disease that has no clock, not knowing when to tick or to tock.

We can not express our pain or feelings through a normal voice, our bad language comes out it was not our choice.

Our paranoia and depression can get very insane, to be sitting around hearing people calling our name.

I will be using my time to continue to rhyme, because this disease will rob us of time.

But if you don’t like something you hear, just remember your not in the shoes that we wear and we really don’t care.

These words our for my brothers and sisters fighting this disease, because if you’re the patient or the caregivers this will drop us to our knees.

But for the time I can still create a voice for us, then it will be me to steer this bus.

So if you read these poems and it helps in some small way than I did something to help CTE warriors today.

The Rock

I once was The Rock, our family power. That was before my brain began to turn sour.

I was a husband and dad, that made it all great. Now every day I have to start with a clean slate.

The things I say and the things I do, often to get a reaction from you….

I go for the jugular, knock you out at the knees, the words that I say only come from CTE.

Now I can’t make decisions or take care of the money, the things happening so quick it’s not even funny.

I put my words down, while I can understand, these words come from my brain, right into my hand.

My hands now express the thoughts and feelings we all go through, where this will lead us, we haven’t a clue.

This disease has no cure, but one thing I can say for sure, with the things that we go through in a day, and still can’t find our way.

To be caught between the stage truth or fiction, causes my brain causes so much friction. So for my warriors without a voice- keep battling the demon like you have no choice.

We may not win this fight, but I’m fighting for the future CTE-ers that just might.

Don’t Give Up On Us

Please don’t give up on us for we know not what we say, please don’t give up, we will forget by the end of the day.

Please don’t give up on us, we know not what we do, please don’t give up , we are just as scared too.

Please don’t give up on us, are care is so tough, please don’t give up, no matter how rough.

Please don’t give up on us, CTE is a disease, please don’t give up, till the beast is on its knees.

My CTE Day

I have a few ideas what I’d like to get done for the day, give it 20 minutes and I forget it anyway.

Pressure in the eyeballs feeling like they want to pop, nothing can help nothing can make it stop.

Then the ocean sounds I have in one ear, the buzz in the other sounds so clear.

I get mean in my mind when I’m in noisy places, wanted to make the noise stop by smashing people’s faces.

Then the paranoias that I go through in a night, hearing the voices then throwing punches like I’m in a fight.

My wife has to wake me because I’m punching my face, I see her fear and I’m not in the right place. I can’t say words nothing coming out the fear so deep but I cannot shout.

Caring for us

Caring for us is challenging, stressful and comes with no reward. It’s our actions and words that strike at your chord.

We behave and believe things that we never have before, our feelings are slipping, our tears are no more, being depressed feeling like we’re under the floor

Our caregivers need a break, but nobody wants to help, can’t find caregivers who understand CTE on Yelp. Not a friend nor a family member, nobody in sight. To get anybody to help is always a fight

We are so mean and hurtful like a devil towards you, but if other people were around, they would think it’s crazy, has to be you! But what they don’t know behind a closed door, we treat you worse because we love you more

It’s our caretakers that take such a strained assault , but to live like we do is nobody’s fault , so don’t be mad at we say or don’t do, because it’s the disease that’s stopped loving you.

If

If I am trying to do something you don’t understand, don’t try to stop me lend me a hand.

If I’m speaking and have some troubles, please don’t correct me it just bursts my bubbles.

Please don’t tell me how great I look. If you only knew the pain I’m in, I could write a book.

If I just blast out with a very inappropriate comment, just shake it off and live in the moment.

If I’m looking confused, there’s nothing you can do. But when I am amused, there is no worry of a fuse.

So being stuck between understanding my fate at one minute of the day, then in the next seconds I can’t remember what to say.

Now as I really am seeing the reactions from my wife and see her fear, it’s only making one thing clear, that if I don’t fight harder my ending is near.

Posted: April 6, 2020

At a time when social distancing and periods of isolation have become a widespread obstacle in the daily life of so many, Gracie Hussey of Memphis, TN is an expert on how to cope.

Gracie sustained her first concussion when she was just 8 years old and went on to suffer several additional concussions throughout her competitive youth soccer career. As she transitioned from middle school to high school, Gracie attempted to hide and fight through worsening Post-Concussion Syndrome symptoms. She suffered from headaches, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to smell, memory issues, and vision difficulties that interfered with her schoolwork and daily life. Eventually, Gracie’s symptoms became so severe she was forced to homeschool for a semester in 10th grade.

Now a college student at the University of Alabama, Gracie was told not to return to campus after spring break to help stop the spread of Coronavirus. For CLF’s webinar, Managing PCS in the Time of Coronavirus, Gracie shared her perspective on living through new social distancing measures and how the experience is similar to periods of inactivity and isolation she dealt with when her PCS symptoms were at their worst. One of the best strategies, Gracie says, is keeping a routine and taking breaks:

“Staying active and trying to keep my routine as normal as possible, even though I’m not allowed to go anywhere besides walking around my neighborhood and working out, has honestly been my savior because I haven’t gotten into the cycle of just lying in a dark room because my head hurts.”

Like so many forced to stay home from school or work, Gracie was concerned the PCS symptoms she’d worked to keep in check would make a comeback. The knowledge that she has conquered her symptoms through discipline, routine, and exercise countless times in the past helps Gracie remain hopeful.

Gracie has been an advocate for concussion safety with the Concussion Legacy Foundation since 2015. Below, Gracie shares her story for the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s Safer Soccer campaign.

Posted: January 21, 2020

“Before the headaches and concussions, he was very much an extrovert, he always had a group of people around him and just loved life and had a lot of fun.”

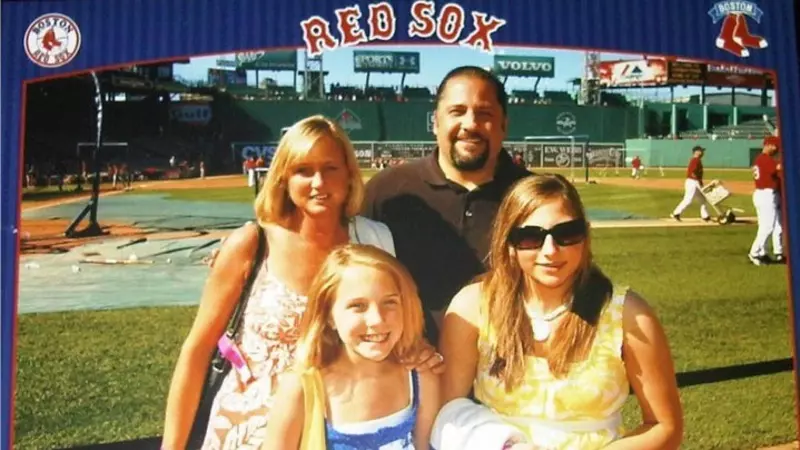

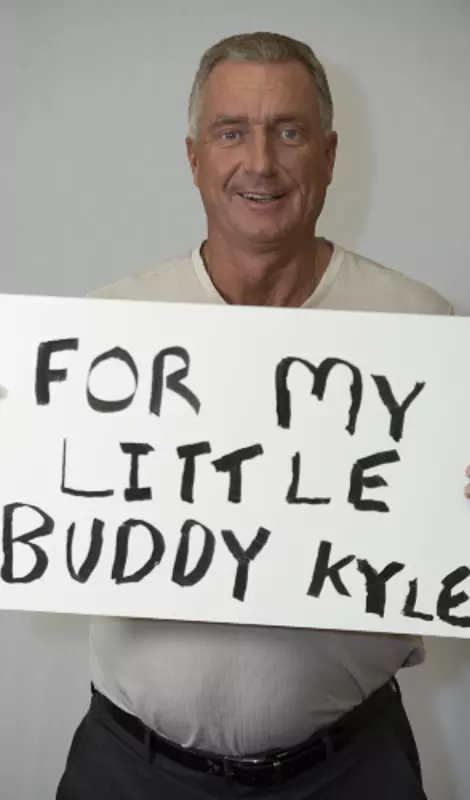

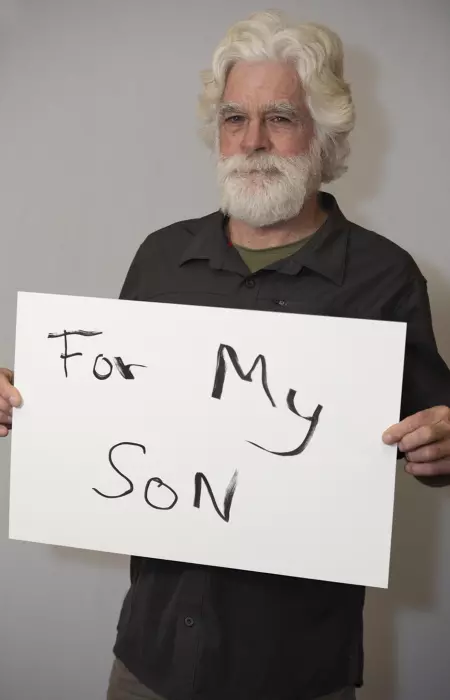

Mike Raarup says concussions changed his son Kyle’s personality. He became impulsive, and struggled with drastic, volatile mood swings. Kyle was a gifted hockey, football and baseball player in Minnesota. Concussions forced him to quit sports in 8th grade – and he was later diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). Treatments helped Kyle graduate high school and attend college, but he still suffered from anxiety, depression and memory loss. He took his own life at age 20 in November 2015.

Kyle’s brain was later studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed with him Stage 1 (of 4) CTE. Mike is proud to have donated his son’s brain to research and supports our cause in his honor. It’s his “Why CLF”.

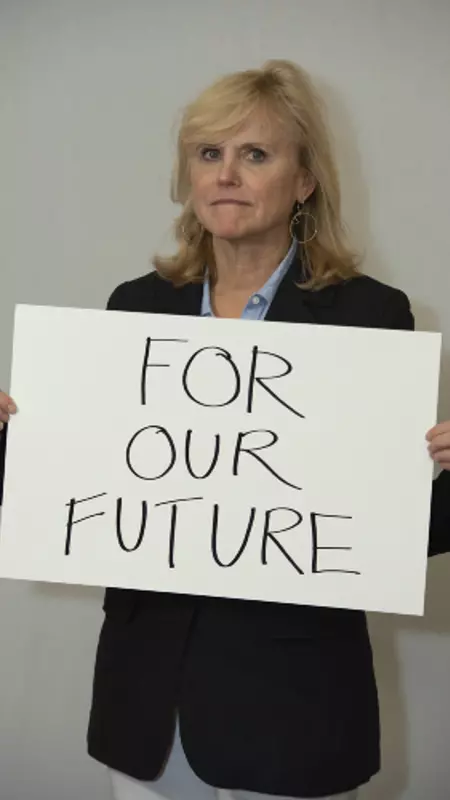

Dr. Ann McKee is leading the global effort to find a cure for CTE with her groundbreaking research. When we asked her why she persists in this work, her answer was simple.

Dr. McKee is the Chief of Neuropathology at the VA Boston Healthcare System and Director of the Boston University CTE Center and the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. In 2018, she was named one of TIME Magazine’s 100 most influential people. Dr. McKee’s work has revolutionized the world’s understanding of CTE and changed the way we think about head trauma in sports and the military. Our future is brighter because of her work.

“He taught all of us life lessons, differently, yet all the same principles. He was our coach in many ways and was very much our hero.”

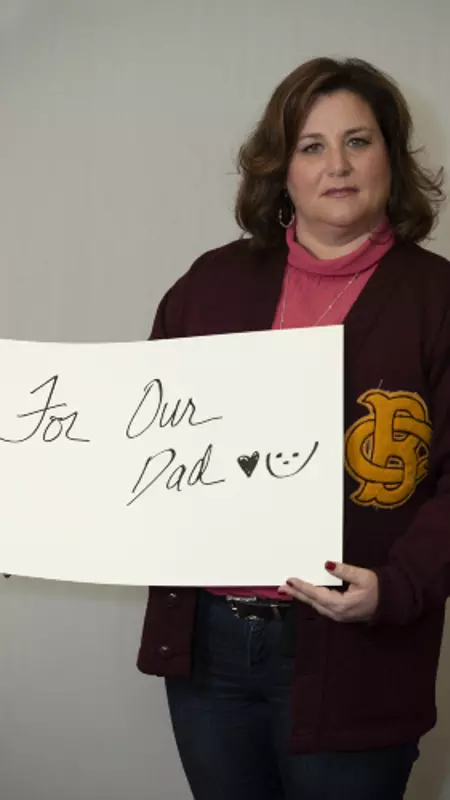

Julé Frechette’s #WhyCLF is for her father John Frechette, who she calls the warmest, kindest, most giving person and best dad to her and her two siblings. John was an offensive and defensive tackle for Boston College before being drafted in 1965 by the Boston Patriots where he played for a season. Frechette also spent a year with the Green Bay Packers playing for legendary coach Vince Lombardi. After a shoulder injury in 1967 ended his football career, he went on to have a successful business career working in labor relations. Signs of memory issues and mood swings began in his mid-50’s and continued to progress. Julé says as her father’s disease progressed, his sadness, frustration and inability to think clearly became more profound and caused him to withdraw and lose his “life of the party” personality. Frechette was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease in his late 60’s and died in 2014 at age 71. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

“The differences came very strongly and very loudly after the last time he played football.”

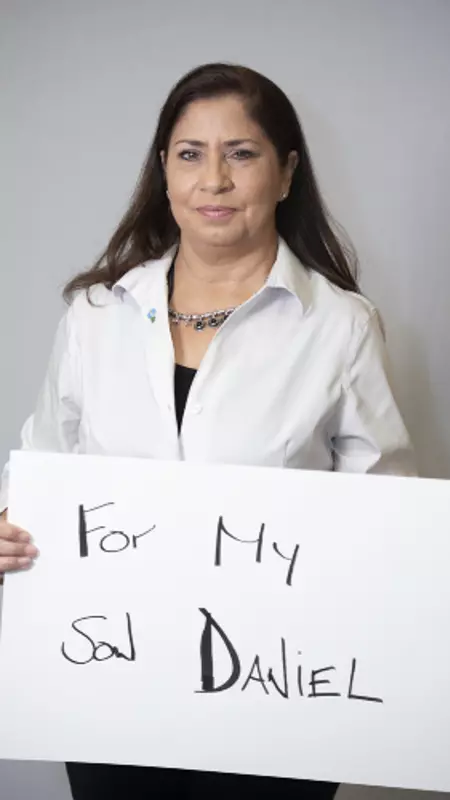

Diana Brett’s son Daniel stopped playing football after a concussion during a high school practice his freshman season. Then she learned he suffered nearly a dozen of concussions before that – and hid his symptoms so he could keep playing. Daniel was diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) and struggled with pain for the next 19 months of his life. In May 2011 he died by suicide at age 16.

Diana is passionate about educating all athletes to speak up about their concussions. She’s also empowering parents to be advocates for their children’s health so they know what to look out for when it comes to concussions. It’s her #WhyCLF.

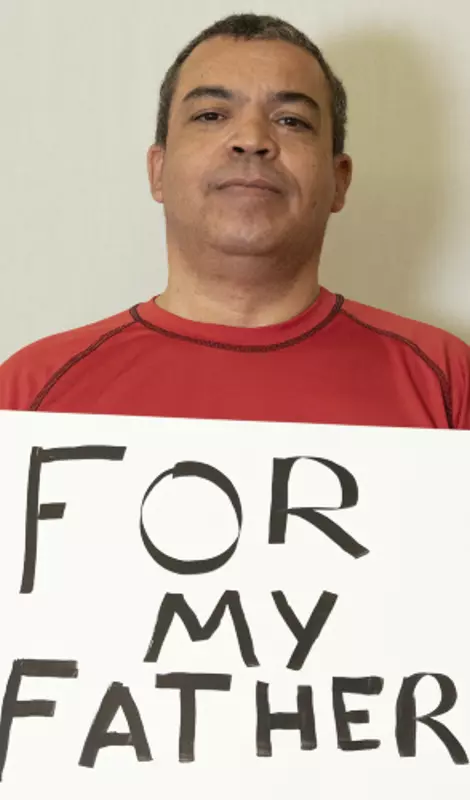

Payton Mincey’s #WhyCLF is for her dad Daniel Brabham.

Daniel was an Air Force veteran, teacher, family man and an all-conference linebacker and fullback at the University of Arkansas before spending six seasons in the NFL with the Houston Oilers and Cincinnati Bengals. Brabham was a lifelong crusader for change. He fought to ban smoking in the workplace in Louisiana and founded the Louisiana Fisherman’s Forum. After his death in 2011 at age 69, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with CTE.

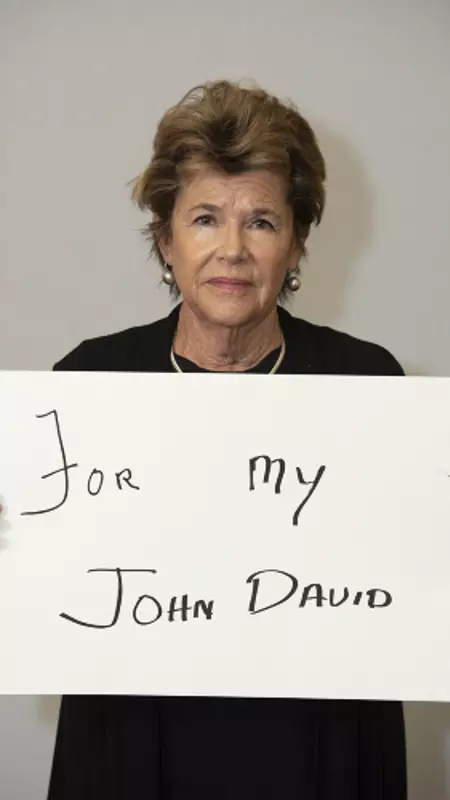

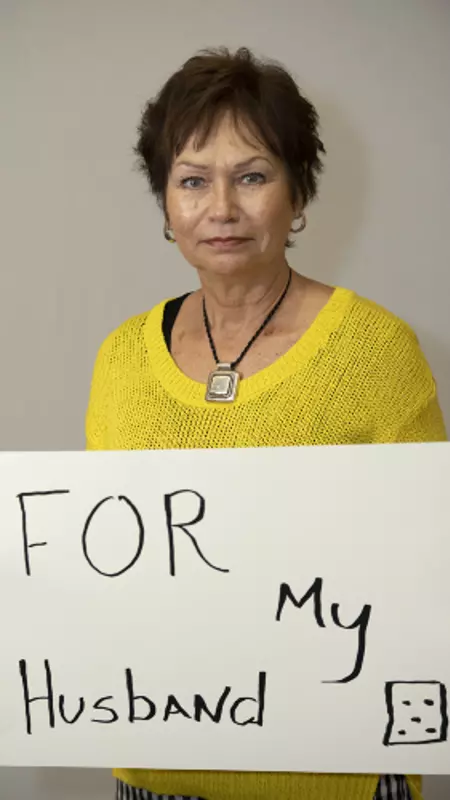

Tough, kind, and larger than life. An All-American football player for Boston College who spent three seasons in the NFL – Pat Frechette’s #WhyCLF is for her husband John David Frechette.

John was an offensive and defensive tackle who was drafted by the Boston Patriots in 1965. A shoulder injury ended his NFL career early, and he transitioned to life as a father of three working in labor relations. In his late 40’s, John started showing signs of depression, memory loss, and mood swings. In 2011 he was officially diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. He died three years later at age 71. The Frechette family says they donated John’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to learn more about how to make the game John loved safer. Researchers at the Brain Bank diagnosed Frechette with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

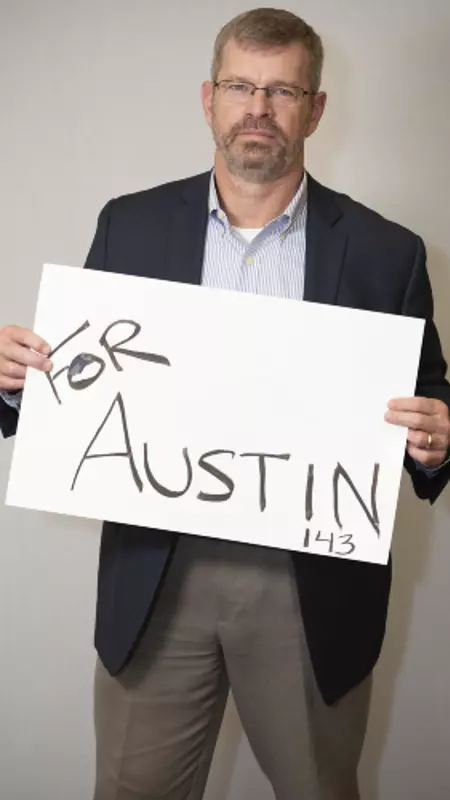

“Everybody loved Austin. He had such an energetic personality and was able to make friends wherever he went.”

Michelle Trenum’s #WhyCLF is for her son Austin. Austin Trenum was a star student and athlete who played football and lacrosse at Brentsville District High School in Virginia. Austin suffered his first diagnosed concussion during his junior football season. A year later in September 2010, he suffered his second diagnosed concussion during a game. Austin took his own life 43 hours later. He was 17 years old. Michelle and her husband Gil donated Austin’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to help advance research about the link between concussions and suicide. They now honor Austin’s legacy by supporting other families who have lost a child to suicide after concussion.

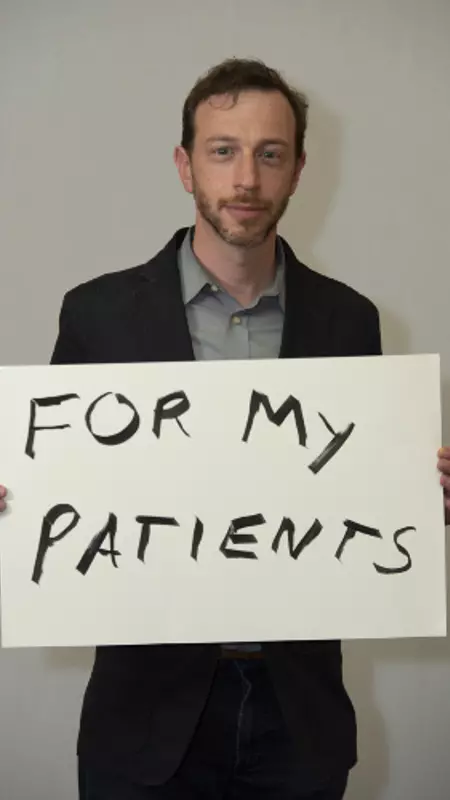

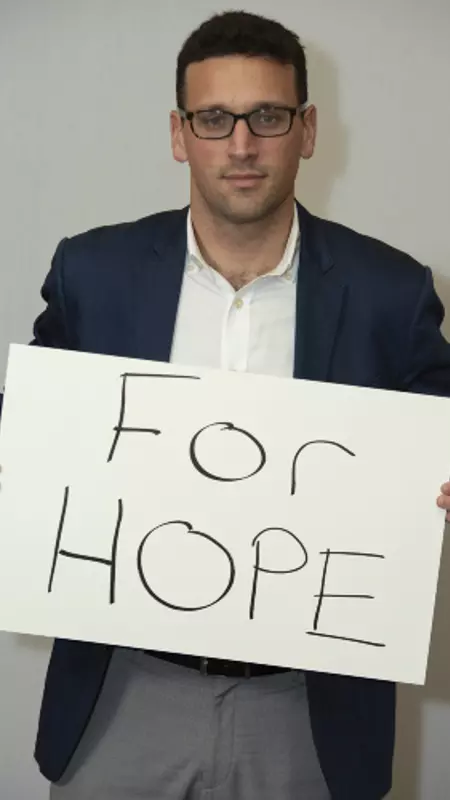

Why is Dr. Jesse Mez so passionate about his work? For his patients.

Dr. Mez is an important member of both the BU CTE Center and BU Alzheimer’s Disease Center research teams. He’s also an Assistant Professor of Neurology at Boston University School of Medicine. Dr. Mez is part of the team that interviews family members and caregivers of Legacy Donors to learn more about their lives and the symptoms they struggled with. His research is helping identify possible risk factors for CTE. Dr. Mez was the lead author on an October 2019 study that found the odds of developing CTE increase 30% for each year of tackle football played.

Quiet, deep, and strong – Joslyn Aitken remembers her son Devin Hands for his caring heart. He’s her #WhyCLF.

Devin grew up in Laguna Beach, CA where he excelled in every sport he played. He started tackle football at age 12 and cherished the “Tough as Nails” award he received for taking so many big hits. Devin loved the outdoors and worked hard to earn the prestigious Eagle Scout rank. Beginning around age 17, Devin struggled with headaches and mood swings. He died of a brain hemorrhage from a fall in 2013 at age 22. Joslyn donated his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to help advance research about concussions.

“My favorite thing about him was his gentleness. They called him a Minnesota Monster on the football field, but he had a second side, a soft side, that I loved.”

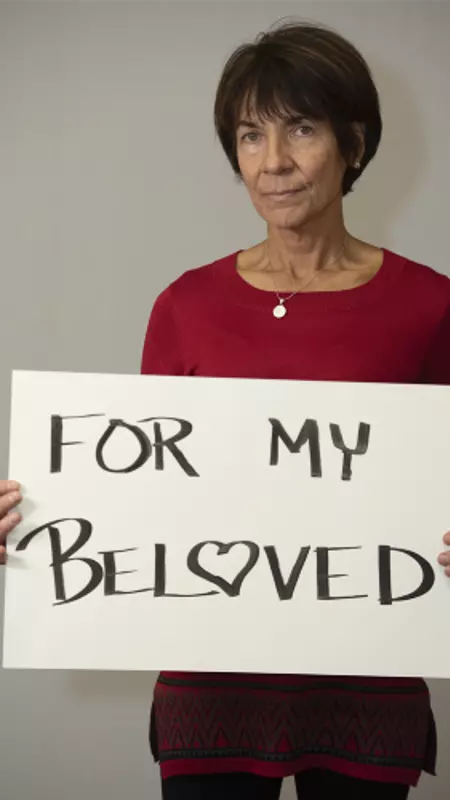

Carolyn Lens says her #WhyCLF is for her sweetheart, her husband of 25 years, Greg Lens.

Greg Lens was a star defensive tackle at Trinity University before being drafted into the NFL in 1971. He played two seasons for the Atlanta Falcons. Lens also served in the U.S. Army, and went on to be a high school teacher and coach in Texas, a job his family said meant so much to him. Near the last decade of his life, Carolyn says she started to notice changes in Greg. He forgot directions to places he’d traveled to hundreds of times. He struggled to tell time. Then the paranoia set in – and Greg battled bouts of aggression and rage. Unable to stay at home, Greg moved in and out of several care facilities during the last years of his life. He died from pneumonia in 2009 at age 64.

Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed Lens with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

Our co-founder and CEO Christopher Nowinski, Ph.D has endless answers for #WhyCLF.

Nowinski was a two-time All-Ivy defensive tackle for Harvard before wrestling in the WWE. His WWE career was cut short after a kick to the head led to Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). Nowinski recognized the desperate need for athletes to understand the serious consequences of concussion, and teamed up with his physician Dr. Robert Cantu to co-found CLF. He’s also a co-founder of the Boston University CTE Center and is driving us toward achieving our vision of a world without CTE and concussion safety without compromise.

Daniel was an all-conference linebacker and fullback at the University of Arkansas before spending six seasons in the NFL with the Houston Oilers and Cincinnati Bengals. Brabham also served in the US Air Force Reserves and was a high school chemistry and math teacher. A lifelong change agent, Daniel fought to ban smoking in the workplace in Louisiana and founded the Louisiana Fisherman’s Forum. After his death in 2011 at age 69, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with CTE.

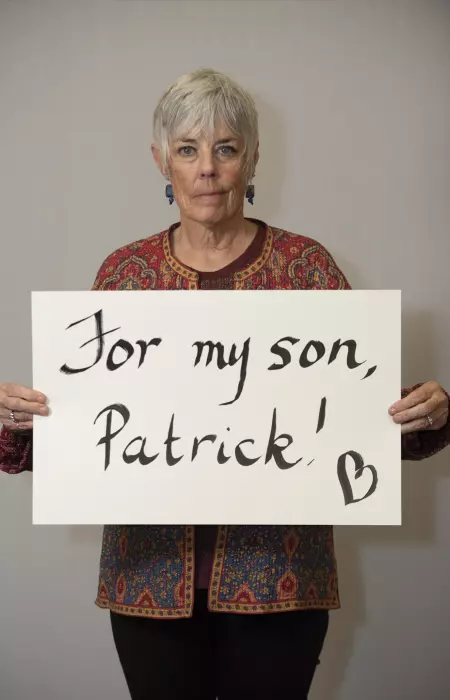

Patrick Grange loved soccer. Everything about it. His mom Michele says he was a natural athlete who was coordinated even as a toddler. He started heading soccer balls for hours on end when he was three years old. A star athlete in high school, Pat continued his soccer career in college playing for the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of New Mexico. He also took his talents to a semi-pro team in Chicago. Michele says he suffered several concussions throughout his career. Then at age 28, he felt weak and knew something was wrong. He was diagnosed with ALS shortly after. Patrick Grange passed away 17 months later. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed Pat as the first former soccer player with #CTE.

Michelle says Pat was a humble, quiet kid, who courageously went public with his ALS diagnosis to help raise awareness for the disease. Now Michelle and her husband Mike honor Pat by sharing his story and advocating to remove repetitive head trauma from youth sports. It’s Michelle’s powerful #WhyCLF.

“He brought smiles to everybody’s faces and was a real inspirational guy who never met a stranger. Just an overall great dad.”

Sarah Naylor’s #WhyCLF is for her father Greg Lens. Lens was a star defensive tackle at Trinity University before being drafted into the NFL in 1971, where he played two seasons for the Atlanta Falcons. Lens also served in the U.S. Army, and went on to be a high school teacher and coach in Texas. Sarah says she first started noticing changes in his behavior when she would come home for breaks in college. He became forgetful and more reserved. Then the mood swings kicked in. By the last year of his life, Sarah recalls him as “the shell of emptiness.” Greg Lens died from pneumonia in 2009 at age 64 and was later diagnosed with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

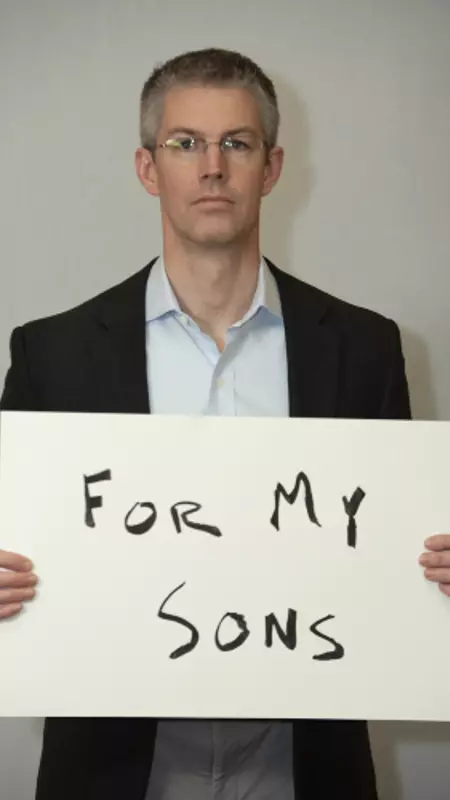

Dr. Thor Stein is dedicated to his work researching CTE so his sons will have a safer future.

Dr. Stein is a neuropathologist at the VA Boston Healthcare System and assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine. He is a part of the Neuropathology Core of the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where he analyzes the brain tissue of CLF Legacy Donors. The work of Dr. Stein and his colleagues is essential to what we do at CLF. Each new diagnosis furthers our understanding of concussion, CTE, and the effects of neurodegenerative brain diseases.

Scott Gilchrist’s #WhyCLF is for his dad Carlton Chester “Cookie” Gilchrist, who started experiencing behavioral symptoms around age 35. Cookie was known for his power and speed as a record-setting running back in the Canadian Football League and American Football League. Gilchrist won two AFL MVP awards playing for the Buffalo Bills in the 1960’s. After his football playing days ended, Cookie turned to a career in business. At home, Scott says the simplest things could make his father upset. He struggled with paranoia, impulse control, and became very reclusive. In the last year of his life he struggled with severe memory, judgement and problem-solving difficulties. He died in January 2011 at age 75. VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank researchers later diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

Scott says now that he has a better understanding of the disease, he has more respect and compassion for what his dad was going through, especially at such a young age.

“Dice was a man who believed that everyone he met held the potential to be his friend.”

Elizabeth Allardice’s #WhyCLF is in memory of her late husband Robert” Dice” Allardice.

Born in 1947, Dice was a football player, wrestler, and boxer at West Point – The US Military Academy. In just one week playing at West Point, Dice suffered three concussions and week later, a broken neck. In 2006, Dice began showing bizarre behavior and struggled with cognitive issues. Those issues progressed over the next eight years before his death in November 2014. He was later diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

Michael Alosco, Ph.D. works to provide hope for those who may be living with CTE.

Dr. Alosco is a neuropsychologist and Assistant Professor of Neurology at the BU School of Medicine, where he also serves as the Co-Director of the BU Alzheimer’s Disease Center Clinical Core. His career has been devoted to investigating the risk factors and biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases like CTE and Alzheimer’s, to help find ways to treat and eventually cure them. He works with the clinical research team at the Boston University CTE Center to learn from Legacy Donor families about their loved one’s history of head trauma, and the symptoms they experienced. This clinical report is presented alongside the pathological findings when the researchers inform families whether or not their loved one had CTE or any other abnormalities in their brain.

Patty Pae was one of the caretakers for her father as he struggled with the debilitating symptoms of CTE for nearly the last decade of his life. The pain and suffering she saw him endure sparked her drive to help others experiencing the same with a loved one. It’s her #WhyCLF.

Patty’s father Dick Proebstle was a quarterback for Michigan State University’s football team in the 1960’s. Concussion-related issues forced him to stop playing after his junior year season. Proebstle went on to have a career in business before symptoms of CTE took over. In the last 20 years of his life he battled aggression, depression, paranoia, anxiety, along with failing executive functioning and speech. He died in 2012 at age 69. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed him with CTE.

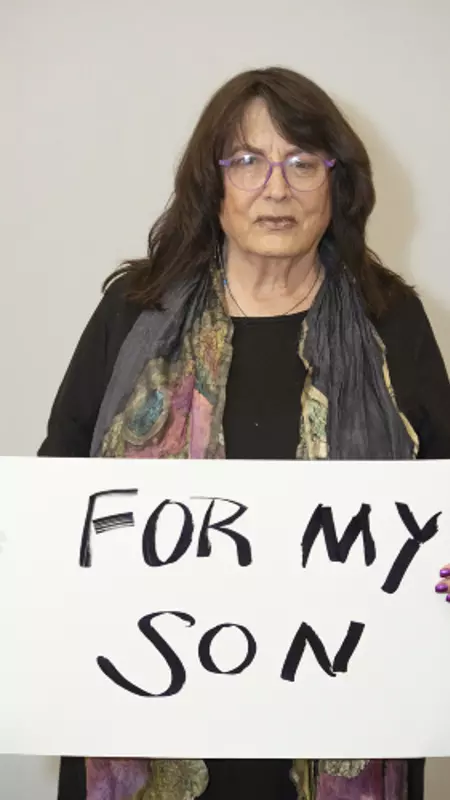

Beth Raarup’s #WhyCLF is for her son Kyle – who she saw struggle with mood swings and depression after a series of concussions at a young age. Kyle Raarup was a sports fanatic who loved playing hockey, football and baseball. Beth says Kyle was a happy kid who was always full of energy, before concussions forced him to quit sports in 8th grade. He was later diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). Treatments helped Kyle graduate high school and attend college, but he continued to suffer from anxiety, depression and memory loss. Kyle took his own life in November 2015 at age 20. His brain was later studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed with him Stage 1 (of 4) CTE.

After Kyle passed away Beth and her husband Mike discovered Kyle liked to use the phrase ELE, or Everybody Loves Everybody, to promote a message of kindness. They say they are proud to honor his legacy of helping others by raising awareness about concussions and CTE.

Mary Hawkins’ #WhyCLF is for her late husband Ross “Rip” Hawkins.

Rip was drafted in the second round of the 1961 NFL Draft by the inaugural Minnesota Vikings team. After making the 1963 Pro Bowl, he retired from football in 1965 to pursue a law degree. He served the Assistant District Attorney for Fulton County, GA and coached high school football in Colorado and Wyoming. He retired to ranch in Wyoming and later became the Wyoming Department of Transportation commissioner and a local municipal judge. Late in life, Rip presented symptoms of Lewy Body Dementia. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE after his death in 2015 at age 76.

“When he was 28 something went wrong. He came to me and said, you know what, I have no power in me. I can’t run, I can’t push off from my feet, I have no power. I’m weak.”

Mike Grange’s son Patrick was diagnosed with ALS at age 28 and passed away 17 months later. Patrick Grange loved the game of soccer. He started heading balls at age three and suffered several concussions during his successful playing career at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of New Mexico, and for a semi-pro team in Chicago. During the last year of his life, Pat courageously went public with his diagnosis to help raise awareness for ALS.

After his death, the Grange family donated Pat’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. He later became the first former soccer player to be diagnosed with #CTE. When you ask Mike Grange #WhyCLF, he says to honor Pat. Mike now advocates to make youth sports safer, so other kids don’t endure repetitive head trauma.

“Jeff was an amazing man. When he walked into a room people would stop and stare. He had an infectious laugh, and was just one of the most kind, loving men I had ever met.”

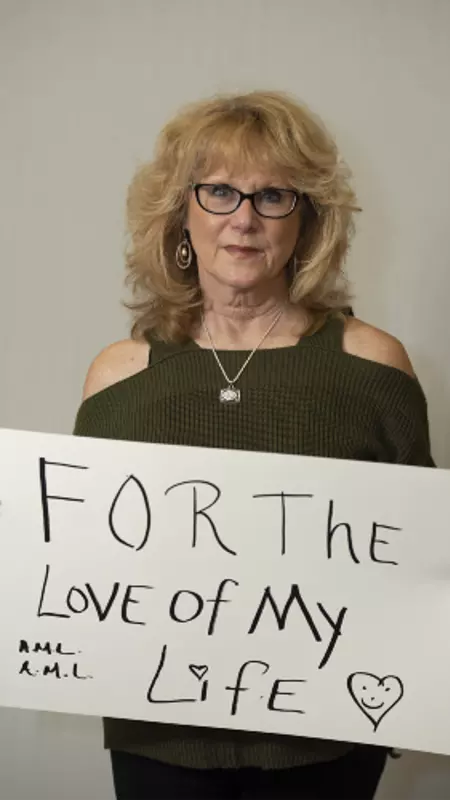

Brandi Winans’ #WhyCLF is for the love of her life, her late husband Jeff Winans.

Jeff was a star athlete growing up in Turlock, California and accomplished his dream of earning a scholarship to play football at the University of Southern California. Jeff won a national championship for the Trojans in 1973 and went on to play six seasons in the NFL. After football, Jeff became a champion for several local causes in Tampa Bay. But headaches, depression, emotional, and cognitive issues affected his decision making, temper, and memory before his death in December 2012. He was later diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

Gil Trenum is dedicated to our cause for his late son Austin Trenum. It’s his #WhyCLF.

Austin played linebacker and fullback as a senior on the Brentsville District High School varsity football team in Virginia. He was a star student who was beloved by his classmates for his vibrant personality. Austin suffered his second diagnosed concussion during a football game in September 2010. He took his life 43 hours later. He was 17 years old. Gil and his wife Michelle donated Austin’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to help advance research about the link between concussions and suicide. They now honor Austin’s legacy by supporting other families who have lost a child to suicide after concussion.

Lisa McHale became our Director of Legacy Family Relations after her husband, former NFL lineman Tom McHale, died tragically of an accidental drug overdose in 2008. Tom later became one of the first former football players to be diagnosed with CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. In her role, Lisa is the liaison between brain donor families and the research teams, guiding families through every step of the donation and diagnosis process.

Lisa’s #WhyCLF is for Tom and the incredible role he played in helping the world understand the long-term effects of repetitive head trauma.

Posted: November 19, 2019

I grew up around the game of football. I was born on Super Bowl Sunday in 1973. My father was a high school football coach in Michigan and the game was a major component of my life from an early age; it was a part of my identity. There are pictures of me as a baby with a football helmet on my head and a football in my lap. As I grew up, I played pickup games of “touch” football in the streets with friends and tackle football in the parks (no pads). Starting in 6th grade through 8th grade we were able to sign up and play organized flag football. At that time, there was not a tackle football program in my hometown for kids younger than high school age. I was a locker room rat and a fixture at high school football practices and games from the second grade on. My story is a bit different from most of those you will find if you do an internet search on football and CTE. I did not play tackle football until freshman year of high school. I was not involved in any organized tackle football program in my early youth, as so many former players were. In retrospect, I feel fortunate to have been limited in my exposure to tackle football in my youth.

I was afforded the insider view of high school football in southwestern Michigan because of my dad’s position as a coach. All I ever wanted to do was play football no matter the weather conditions or time of year. Growing up I felt football was my destiny, what I was meant to do, who I was meant to be. To say I loved the game of football would be an understatement. I dreamed of the day I would play high school football for my dad’s team, of the day I would sign a letter of intent to play in college, of the day I would play football in college and of the days I would be drafted and start my career in the NFL. That is a dream many young men have. As we all come to understand, dreams like that don’t always come to pass for a variety of reasons.

The majority of the head trauma I experienced came from playing football during high school and college. I was a starter on both offense and defense throughout high school. Most of the colleges who showed interest in me were Division II schools. It had been my dream to play Division I college football. I was honored the coaching staff at Central Michigan University saw enough in me that they believed I may be able to play at the Division I level. I went to Central Michigan in 1991 as a preferred walk-on, meaning I was not given an athletic scholarship to play football. I would be paying for tuition, room/board and books like any other student on campus, but I saw this as opportunity to achieve one of my life’s dreams and hoped I could earn a scholarship.

I played safety and spent my first year as a redshirt on the defensive scout team. My goal was to play as much in practice as possible. While I was not as fast as many of my teammates in the defensive secondary I was—to paraphrase several of my former coaches—a “hitter.” Hitting in football always came easy for me. I was taught from an early age to see what you hit, to put your nose on what you hit. If you do that, the risk of neck injuries by compression is lessened. That was always my thought process, see what you hit and go and hit that person as hard as you possibly can. This mentality served me well throughout college and in my development as a player. I started to get playing time in games during my redshirt sophomore year which continued during my redshirt junior year.

I became a special-teams player and saw some game action in the secondary, but it was typically end of game play. My special-teams play included kick off, punt and punt return teams. I’m outlining this because I believe there may be someone out there who can relate to my story. I may not have started for my college team, but my passion in college was the game. I was involved in every practice in the fall and spring with that team. I hit every day we practiced with helmets and shells, with some exceptions due to regulations.

Throughout my high school and college playing careers I had my “bell rung” on multiple occasions. I know now these were likely concussions of varying degrees. This never stopped me from continuing to practice and/or play the game I loved. Toughness and determination were attributes which allowed me to push through. The way I tackled, essentially leading with my face (not the crown of my head) resulted in multiple sub-concussive impacts each practice. This lasted from August until November for 8 years. This also included practices in the months of March and April for three years while I was in college. My football career ended in 1994. I did not play professionally, nor was I involved in any semi-pro or amateur leagues. I have had no trauma to my head in the years since I finished playing.

After college, my life seemed to move along well. I met and married my former wife while at CMU. The best men in my wedding were my fellow teammates, my best friends. The university welcomed me back in 1997 as a graduate assistant coach working with the football team. I was engaged to be married on the campus of CMU. You see, many milestone events and lifelong relationships are the result of making the decision to play football at CMU. This is part of the complicated relationship I have with the game. Afterwards, life moved along like it does for the majority of former college football players—without football.

As is the case with many things, I was not the person who first noticed changes to my personality. It was my wife at the time who saw subtle changes in me become more noticeable and not so subtle.

These included the following:

These symptoms slowly became part of my personality. My wife at the time raised her concerns to me in the fall of 2016. This was shortly after our second separation. Some of the reasons for the separation were my aggressive, angry, erratic behavior, irritability and mood swings. She told me she was afraid I was showing signs of CTE. I will admit that at first, I didn’t buy into what she was telling me.

I balked at her suggestion for a couple of months and thought the symptom patterns she pointed to were coincidental. But something happened as I sat alone at night with my thoughts. I noticed some things I had attributed to coincidence may not be at all. I was not able to always understand people when they were talking to me—I could hear their voice but not understand any of their words. At times, when speaking, I was unable to find the words I wanted to use. I was angry more often about insignificant things and I noticed big mood swings. There were times I had to leave and try and get in a quiet environment because any sounds, even a whisper, felt like a pick into my brain. I remembered I had been having problems with dropping items out of my left hand, and my left hand would show signs of tremors at various times. These symptoms became a part of who I was so gradually that it was hard for me to notice. I had been coping with them and living with them, but in retrospect these symptoms became my new normal over the previous 4-5 years.

At first, I didn’t believe my wife. Then, I didn’t believe myself. I thought it was all in my head. But educating myself on CTE, current research, and stories from others experiencing similar symptoms has helped me understand that what I am experiencing may not be coincidence. CTE is real, there is ample evidence to back it up, and it may be the cause of my symptoms. I am constantly looking at the research and my symptoms to remind myself that what I am going through is legitimate and what other people are going through is legitimate and there is support out there.

As I stated earlier, many of the best things in my life were the result of making the decision to play football at CMU. The game of football has always been a part of who I am. That is why I now have such a complicated relationship with the game I grew up loving. I don’t know how prevalent CTE is among former players, that is not my role in this story. I simply know these symptoms, which are consistent with those of CTE, are my reality.

Imagine blinding pain and the feeling that an ice pick is being driven into your brain, and the cause is your friend at the front of the church speaking in a “normal” tone. The pain in your head is so bad you can’t understand the words and must excuse yourself and leave the service. You become aware of intermittent tremors in your left hand; a type of feedback you’d never experienced before. You observe difficulty with fine motor skills, such as picking things up with that hand, and create rationalizations as you drop things out of the same hand (something you have never done) while not truly understanding the underlying reason.

Now imagine irritability. Not just normal grumpiness, but explosive anger at people you love, strangers, and situations in general. It doesn’t occur in dramatic situations where a lot of emotion may reasonably be expected, they are normal, everyday life situations.

Imagine stuttering and stammering, being unable to find the appropriate words when speaking. You feel frustrated by speech and communication, once a cornerstone of your personality, and watch it erode to something that is no longer a strength. Add forgetfulness—not being able to recall what you were speaking about and details about recent interactions. Wondering whether you performed a task you were going to do or if you still need to do it.

Any one of these symptoms may not mean a lot standing on their own. They are symptoms millions of people encounter as they move through the various phases of life. When these symptoms are experienced together or with a multitude of other symptoms, as happened to me, it may be evidence of a bigger issue. I was left angry, confused and numb. I couldn’t comprehend what was happening to me, I wasn’t able to put the pieces together. I needed help and after that I needed hope, which is why I am sharing my experiences. If I can be that hope for someone else, it is worth being vulnerable.

Once I accepted what I was experiencing was tangible and real, the next task was finding treatment. This task loomed large and initially seemed quite daunting. I was fortunate that I was referred to a doctor by my wife at the time who wanted to treat me and help. Currently there is no cure for CTE. It is classified as a neurodegenerative disease. Physicians are able to treat various symptoms to slow their progression, but not the underlying disease. I have searched and tried various treatments that have provided various levels of relief from the symptoms.

These include meditation, physical activity, a diet high in plant-based nutrition (my diet does include some meat), neurofeedback, infrared laser treatments and putting a safety net in place. The treatments seem to vary in their efficacy. I have not been able to figure out the reason for this, but I will continue to study, track, and educate myself on what works for me.

The point I want to make is that there is help out there. Even if it is just treating your symptoms. There is help available from caring physicians and support groups who want to help you manage your condition. Keep looking for those special folks who embrace this challenge and are not cowed by it.

This path seemed solitary for much of the first year. I felt it was a journey I would need to take alone. I could not have been more wrong. When I was a player I thrived in the atmosphere of the team, the comradery of the team. This fight for myself and the thousands out there like me has to be done the same way. We have to be there for each other, even if that is all we have. I have embraced this attitude and feel fortunate to have people in my life who want to understand and are willing to travel this journey to provide support.

The week my then wife approached me with her concerns regarding my symptoms, Rashaan Salaam, former Heisman Trophy winner from the University of Colorado, died by suicide on a park bench in Boulder, Colorado. The news affected me deeply. It happened approximately 40 miles from where I was living at the time. I did not know Rashaan, though we were playing college football in the same era and living in the Denver, CO area. I do not know what was going on in his life or what events led him to make the choice he made. We do not know if he had CTE (Rashaan’s brain was not studied because of religious reasons) but it was reported family and friends said he displayed symptoms of CTE. I am not able to speak to his experience firsthand, but I do know that when what you are experiencing is validated by people in your life there is a peace in feeling like someone understands what you are going through. I hope that whatever else was happening in his life, he found that peace.

That thought continued to play in my mind as I decided whether to write this story down. I was initially reluctant to tell it. There are only a very small number of people who know what I am experiencing. I have been very private about it for many reasons, including not wanting to worry family members or think of what the future may look like with them. One of my biggest fears was that I was somehow letting down my former teammates and coaches, including my late father. I was afraid they may see me sharing my story as an attack on them, our team, our family and the game we all loved so much. This is in no way an attack, but rather a call for us to support each other.

My life has changed over the last several years since I started to recognize the symptoms that have become a part of my life. I am no longer married and there are times when things are a struggle, when treatments don’t seem to be working and I just want my old self back. These are the times that I have to force myself to lean on those close to me. It is in those times that I make sure I fall back on my faith in God, my beliefs, and the support and safety net of loved ones I have put in place. I will tell you that my life is better than it has been in recent years because I have made the decision to live mindfully, daily. I am blessed that I am able to fight. I am blessed because there are people in my life who try to understand what is going on and are there for me.

The growing knowledge about CTE and the experience of others gives me a sense of peace. I don’t have to question whether what I am experiencing is quantifiable to fight it. I will tell you these symptoms, be they CTE or something else, will be battled until the very end, whenever that may be. I am not defeated but instead facing this challenge head on. A wise man once told me that you shouldn’t be afraid of a diagnosis, what a diagnosis allows you to do is to make a plan to effectively treat and fight the cause of that diagnosis.

There are times of loneliness and that is when we need our family, friends and brothers. Though we may not have played for the same team in the past, we are on the same team now. We need to be there for each other, to support each other and to help each other in these battles. The fight against TBI, CTE and those symptoms consistent with CTE has gotten much larger than my privacy and any fear I may have had of being negatively labeled.

Maybe you love someone who is going through similar experiences. My hope is that my story provides some level of insight. Maybe you are the one experiencing similar symptoms, that you are feeling lost, confused, angry and defeated. If so, please know that you are not alone and there is help. These symptoms do not define you. They are not the end of your story. They are simply one more part of your journey, a journey that does not have to be taken alone. If there is one person out there in this world who sees and relates to my experience it has been a worthy cause.

Posted: February 1, 2021

My husband and I celebrated our 46th anniversary on June 1st, 2019. It was a celebration filled with many memories of our lives together that, sadly, only one of us can grasp.

My husband Steve suffers from what doctors tell us is a probable diagnosis of the degenerative brain disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). When we were married 46 years ago, we began our lives together as minister and wife. We pastored churches in Maine, New York, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania until he retired in 2016. At that time, we had no idea what was causing his myriad of debilitating and bizarre symptoms.

Steve grew up not far from New York City and was heavily involved in sports. He found solace in competition as an outlet where he could excel and receive the recognition he longed for. He was a gifted gymnast and played baseball and basketball; but his greatest love was football. He started playing his freshman year of high school and continued all four years in positions for which he was totally unqualified. He was 5’9″ and barely reached 140 pounds. Nonetheless, he played everything from lineman to quarterback with the drive of a professional athlete at the top of his game. During that time, he had five concussions bad enough to take him out of games.

He may have suffered several others that went undiagnosed because he played through them. We’ll never know. What we do know is that Steve never missed a single game in those four years, playing for a team that only lost once during his career. Looking back, we realize that means Steve took thousands of potentially damaging hits to the head during his high school career, including one that even broke his helmet in a game. It wasn’t until years later we discovered, from tests showing evidence of trauma, he must have fractured his skull from the hit.

Steve was offered an athletic scholarship to play football at a small college but, in a decision that seems more like a miracle now, he opted to train for ministry at a bible college instead. It was there where Steve and I met back in 1971. After college, we settled in upstate New York so he could continue his career as a pastor. Steve missed playing sports, though, and decided to try out for a semi-pro football team near Albany. He made the team, but my gut told me it was a bad decision, and I pushed back. At the time I didn’t know much about brain trauma, but now I’m incredibly thankful I put my foot down.

Throughout our marriage Steve sustained 15 more concussions that we could document, most of which were caused by recreational basketball. One was from a bad fall down the stairs, another happened during a car accident, and one of the most severe was when he took a line-drive softball to the temple. It seemed to become easier and easier for him to get a concussion even with a relatively light hit. The very last one occurred when he hit his head on the bottom of a table and lost consciousness.

Steve’s present condition did not come on quickly but was more of a slow decline with so many symptoms that did not seem related at the time. He has been treated for depression since 1996 and probably should have started that treatment sooner. He began having migraines around that time. He began drinking regularly and showed other signs of poor judgment and became very impulsive. He would occasionally have memory blackouts where he couldn’t recall where he had been or what he had done. We didn’t mention any of these symptoms to our doctor, though, because they weren’t happening on a regular basis.

In 2000 we moved to Pennsylvania. Steve’s drinking and blackouts became more frequent. We left ministry entirely after he spent a week in a psychiatric hospital followed by a 14-day stay in a rehab facility.

No longer a pastor, Steve struggled to find a place of employment. He found work with the county human service department as a caseworker and then with the probation department as a juvenile probation officer. In 2009 we took up church ministry again and kept at it until 2016 when he finally decided he could no longer manage the responsibility. There were times when Steve would go blank in the pulpit and forget what he was supposed to say and do.

During that time, he also started studying to get a master’s degree in counseling and planned to open a practice after he retired. He had to give that up just short of graduating because the cognitive demands of the studies became too much to handle. He later received a counseling certificate in the hopes of gaining traction again.

In 2016, we moved to our current home to be near our daughter and family. Steve picked up part-time work as a drug counselor. Ordinarily this would have been a good fit if he had been healthy in body and mind, but it instead became an opportunity for him to become involved in drugs himself. His use of crack cocaine and heroin went on for about six weeks. He nearly died before I tracked down what was going on. By then I knew our world was falling apart and he had totally lost control.

What followed was two stays in a residential rehab center and one suicide attempt. We made a trip back to the neurologist who was treating him for migraines. He did more testing and finally came out with the probable diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). I was floored. For one thing, I had no idea exactly what it meant regarding a prognosis. Could CTE be treated or cured? As we talked to the doctor it became clear it was most likely the root of Steve’s problems for years, but we didn’t realize it.

This doctor was the first to ask us to write down Steve’s concussion history, dating all the way back to high school. It was like the light came on in a very dark room and we could see the pieces come together.

The doctor then put together a drug regimen to treat Steve’s various symptoms, especially the depression. We also went to a psychiatrist who was able to tweak the drugs a little more and address the hallucinations and insomnia. Steve is also diabetic, has high blood pressure, and restless leg syndrome. We are blessed to have a general practitioner who has treated Steve for years for the more common issues but was quick to educate himself about CTE to support the specialist’s directions.

It was around this time I had to face what Steve’s illness had done to our finances. There were loans and lines of credit I wasn’t aware of and the credit cards were maxed out. Then I discovered he had been selling the few valuable things we owned. I got him to sign a power of attorney over to me so I could deal with the finances without his input. It was quickly apparent that bankruptcy was the only way to save the house and get rid of the debt.

Even with good insurance the medical bills started piling up. That was when I went to the Office of Aging here in Pennsylvania and sought help. Since we are both on social security and I only work part-time, we easily qualified for Medicaid. I had to swallow my pride and accept any assistance that was available. Thanks to this assistance, we now have a nursing aide who will stay with Steve while I work to ease the burden on family members who are assisting as well.

Dealing with this disease is a daily journey and I’ve learned each day will be different. He may feel like going for a walk one day, but the next he will barely move or speak. At any given time, he may lose speech, sight, leg function, memory, voice, or appetite. He may forget where he is, forget a person, forget the day of the week, the time, or who has died in his past. He becomes belligerent but not violent and lacks emotion but is still suicidal. The most difficult part is coping with the brief moments of normalcy, where Steve is coherent and can understand he is ill and knows he will only get worse. It’s a constant battle of one step forward and three steps back.

We are both sustained by a circle of faithful friends and our faith in a God who still cares and watches over us. We will continue to move forward and deal with each day as it presents.

We know there are many other families struggling to care for a loved one with possible CTE. We’re praying for them to receive God’s grace to sustain them during difficult times.

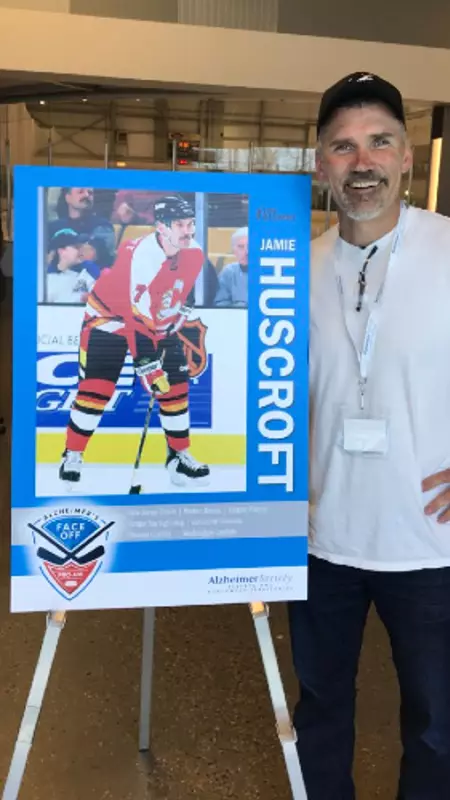

Posted: October 25, 2019

That included hiding every injury that he could for fear of losing his job. Huscroft estimates he suffered at least 14 concussions through his career. In 2001, after several concussions compounded to the point that he could no longer hide the symptoms, he had to walk away.

Huscroft now works as a director of facilities for a nonprofit hockey association in Washington. He’s surrounded by the game he loves and enjoys giving back to the hockey community. He is working hard to make sure the old culture of unnecessary hits and hiding hockey injuries is a thing of the past. To that end, Huscroft brought the Team Up Against Concussions education program to coaches and athletes at Sno-King Ice Sports as part of USA Hockey’s Team Up Against Concussions Week.

In the interview below, Huscroft talks about his love for the game, how concussions impacted his career, and the importance of sharing the Team Up Against Concussions message.

Playing professional hockey was never on the forefront of my mind growing up. I came from a small town in British Columbia and everybody played hockey. If there were 15 boys in the class, 14 of them played hockey. On weekends we all gathered around and watched Hockey Night in Canada. It was just something we did for fun. I never thought it would take me anywhere.

When I finally did start playing more seriously in junior hockey, I loved the culture, the players, the coaching. It really taught me hard work. If you had even an inclination or a thought of moving on to the next level, you had to work hard. That attitude continued on throughout my career. When I got drafted into the NHL the reality was that a mistake could cost you everything. Especially if you were someone with my talent. I didn’t have much talent. I worked hard and I was tough, but I lived on that fringe every day where I woke up every day not knowing how long I’d have a job.

That experience really helped me in the second phase of my life and career. It prepared me for all kinds of things. I work for a nonprofit hockey association and I have for the past 15 years. I’m surrounded by kids and people who want to be at the rink every day. It’s great. Every day I wake up and thank the good Lord that he gave me the chance to play in the best league in the world for quite some time.

Back in the day, most of us didn’t want to take a game off. I remember Kenny Daneyko who was the fiercest warrior I’ve ever played with or against in the NHL. There were times that his teeth got taken out, his finger was broken, or his foot got broken with a slapshot or something and I’d say to him, “Kenny – why don’t you take a couple games off and let me play?” I was the 7th defensemen and could have filled in. He said to me, “Husky, if I let you play, I may never get in the lineup again.” And I’d say, “Yea you will, you’re Kenny Daneyko!” But things like that made me feel like it didn’t matter what happened—you couldn’t sit out a game.

I wound up with at least 14 concussions. There were times that I’d take a big check and I’d get knocked out, but I’d be able to get right up. If anyone asked what happened, I’d tell them my knee went out or my shoulder was hurt but I would never let them know that I got knocked out. Unless it was blatantly obvious, because if I got known for having a glass-jaw or not being able to take a hit then by golly I wouldn’t have a job the next contract.

I was in Vancouver when I was probably close to 30-years-old. I played three exhibition games in a row and I got knocked out three times in a row over the course of a week. That was the beginning of the end for me. There is nothing you can do to hide the injury at that point. I think the hits were from a fight, an elbow, and a simple hit to the boards. It buckled my knees every time, but I got right up because that was my job. I knew that if I said I got a concussion, I could be out for months and I wouldn’t be sure if I was coming back to a contract or not. So out of pure stupidity I didn’t speak up.

I look back and I think “why did I do that?” But that was your life when you were in the thick of a career. That’s all you knew. You just said, “I’m a warrior. I’ll get around it and persevere.” Well, that didn’t happen, and my symptoms stuck with me. A year after that I took a simple body check in an AHL game and I never recovered. I was out of the game, and it kept me out.

I had deep, dark symptoms. The whole bit. But I was one of the ones who came out of it. I had a good support system. I rebounded and I luckily got a job in business where I was exercising my brain and working out physically on my own. I rebounded and I’m very fortunate.

No matter where you are and what you’re doing, if you’re playing sports concussions are a possibility. It all stems at the top with your team manager or coach. With Team Up, it’s vitally and critically important that we all get the coaches and managers and players to spread that message that teammates have a responsibility to look out for each other when it comes to concussions. It is so important that we recognize concussions on the ice or on the bench. To do that we get need to teach players the Team Up message in the locker room, on the team bus, and on the ice.

You can’t tough out a concussion. I think coaches all know about it, and I think USA hockey and Hockey Canada have done a lot to educate all these coaches throughout the Level 1-5 courses that athletes can’t tough out concussions. We know to respect concussions, and the challenge is to respond accordingly. The awareness is 100-fold now compared to when I was a kid.

In my day, in the 80s, we knew what concussions were, but we didn’t change our behavior much. Now that we all know and respect concussions, we know that you have to be really careful. Sports, especially hockey, has done a great job taking steps to protect our youth. There is no hitting until you get to the 13-year-old level. Even then the hitting is at the top tiers. Very few hockey players will ever go on to experience the full-contact game. Kudos to USA Hockey and the NHL for adapting, bringing this issue to the forefront, and protecting our youth.

Across the board leagues are taking unnecessary hitting out of the game. I oversee about 700 athletes in our adult league right now and I’m on the discipline committee. We do not accept hitting. If you take a run at somebody and hit them and knock them over, that’s it – you’re suspended. And if you do it a couple of times, we kick you right out of the league. And youth they’re doing the same thing. Kudos to all the people that are advancing this culture change.

Posted: October 4, 2019

“If I woke up this morning, I’m winning.” Rap lyrics from 2 Chainz that really hit home. Not only do I strive to live each day with a grateful heart, but as someone with epilepsy I go to bed each night knowing I may have multiple seizures in my sleep, if I wake up the next morning, it is truly a blessing.

That’s how I’ve learned to see my life with epilepsy – as a blessing. Every day I choose to focus on what I can do, instead of what I can’t. If you’re out there living with epilepsy, living with seizures in any way, I hope I can inspire you to do the same.

I’ve had an eight-year journey with epilepsy. I developed it in my early 20’s during my football career. I detail my concussion history and the beginning of my experience with seizures and how it impacted my relationships in the piece, “How Football Changed my Life.” It’s been a long road, with some serious lows, but living with epilepsy has taught me so much. It’s taught me that greatness isn’t reaching every goal in life, greatness is the maximum effort you’re able to give – win, lose or draw. Not everyone will beat epilepsy, but I want us all to find greatness in the fight, in knowing we’re trying.

I try to live with an EPIC mindset, and I want to encourage you to do the same. EPIC stands for epilepsy, pride, inspiration and courage. Epilepsy looks different for each of the 40 million people in the world who suffer from it. It’s a chronic neurological disorder that produces brief disturbances in the normal electrical functions of the brain, causing recurrent seizures. Some people are born with it. Others develop it later in life from a brain injury, brain tumor, stroke or other reasons. Some have grand mal seizures, others don’t. Along with seizures, many have debilitating headaches, nausea, memory loss and fatigue.

No matter what your experience with epilepsy looks like, I want you to know people are capable of loving you, and people are capable of understanding what you’re going through. It’s easy to put walls up, but sometimes we have to let our guard down and figure out a way to get through to society, so they see beyond our seizures and realize we’re humans too. We have bills, stress, trials and daily obstacles we face just like anybody else, yet we get looked at like we’re lazy bums. Trust me, I want to go to work, but I don’t want to have a seizure and put somebody in harm’s way. Many of us are unable to work with our conditions, but we still have to find a way to provide and live in a world where money is key in everything you do or want to be.

Imagine, out of nowhere, your body jerking violently out of your control. Or you lose the ability to control your speech. Sometimes you go completely blank, as if you’re stuck in space for a short period of time. A seizure can hit at any moment, at any time. The very noticeable symptoms are hard to hide. We need to spread more cultural awareness of seizures, so people can understand what we’re going through and realize in those scary moments, we need someone to help us, not make fun of us. It’s easy to be embarrassed, but I want to be part of a movement where we erase the shame and realize the epilepsy is not our fault. We didn’t ask for this, but it’s our reality and we have to find the strength to get through it.

I won’t accept epilepsy beating me down or getting in my way of bettering myself. It’s all about going out there and just trying every day. Being misunderstood in society can cause a lot of pain. I walk around looking like a “normal” person. People say I don’t look like I have seizures, I look athletic. While that can be hard to hear, I have to accept that some people will listen when I try to explain my condition and others won’t. The epilepsy community needs to be there to support each other and offer that understanding. We are in a unique position and what we’re going through completely changes lives.

Epilepsy is a monster. It’s so humbling and eye opening to try and understand something you’ve never seen. I’ve never seen someone have a grand mal seizure. It’s amazing when you have people around you who can recognize it and take care of you. I have friends who tell me they caught me before I fell and laid me down because they knew what was going on. It’s scary to lose all control of your body and mind during a seizure, but I’ve learned how to have enough pride to accept help. Let’s all have enough pride to get up every day with epilepsy and try our hardest, but not the sort of false pride where we don’t let people in. It’s easy to push people away because you’re caught up in yourself and your own struggles, but when somebody is there for you, don’t misconstrue it. Try to remind yourself they’re facing struggles as well and you must be there for them too. Let’s have enough pride to be honest about what we’re going through. I want to be able to admit to my wife that I don’t remember things that happened at our wedding. It’s frustrating not to remember, but I have enough pride not to lie, and to own my illness and its symptoms. You must have enough pride to look past people’s opinions about your injury. If you let the negativity bother you, you can lose yourself. Instead, let’s work together to educate people on what to do when they see someone having a seizure.

Posted: September 10, 2019

The University of Northern Iowa junior and her teammates have a unique understanding of the value of concussion safety. Current UNI women’s rugby head coach Meghan Flanigan makes it a priority to educate her athletes on brain trauma and concussions, to honor the program’s former longtime coach Steve Murra. Murra passed away in 2016 and was later diagnosed by researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank with Stage II CTE.

Murra’s passing started a lasting conversation about concussions and brain trauma within the eastern Iowa community. Flanigan, who played for Murra, says the team aims to continue his legacy by doing more than just playing excellent rugby. Many athletes on the team pledged to donate their brains for research at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank and have delivered the Team Up Speak Up Speech each year since 2016.

After learning about Murra’s passing when she joined the team her freshman year, Kleyer worked to gain a stronger understanding of concussions and CTE.

“In high school I didn’t really think concussions were a big deal,” Kleyer said. “Knowing the signs and symptoms of a concussion definitely has opened my eyes to seeing what I need to do to take care of my body.”

During a 2018 all-star rugby game, Kleyer put her knowledge into practice. She noticed her teammate took a hard hit to the head. When asked if she felt alright, Kleyer’s teammate was quick to say she was fine, but Kleyer kept a watchful eye on her friend as they continued the match. A few plays later, her teammate took another bad hit.

“I could definitely tell right away something was up and she wasn’t doing OK,” Kleyer said.

She noticed her teammate was getting up much slower than usual.

“Our ‘thing’ as a team is to push each other if we are ever winded,” Kleyer said. “We’ll say, ‘get up! You’re OK!’”

In this situation, though, she could tell her teammate was suffering from something more serious than fatigue. Kleyer told fellow teammates to help her injured friend as she brought the situation to Coach Flanigan’s attention.

“I was talking to some other coaches trying to form a game plan when I heard the ref’s whistle blow,” Flanigan said. “I heard Kleyer screaming my name and saw her talking to the refs.”

The injured player was brought off the field and evaluated. Doctors eventually diagnosed her with a concussion. Kleyer made sure to check up on her daily during her recovery as she sat out from classes and practice.

The best teammates, like Kleyer, care more about the health and wellbeing of their teammates than they do about winning or losing. If it weren’t for Kleyer’s leadership, her teammate could’ve continued to play and risked developing serious health consequences like Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS), or even Second Impact Syndrome (SIS), a rare condition that is often fatal when it occurs.

By working with the team’s Athletic Trainer and following their return to play protocol, Kleyer’s teammate was able to take the field again later that season.

“Had we not been proactive in saying something she could’ve been out a lot longer,” Kleyer said. “She was able to continue playing later on…that gave me happiness.”

Coach Flanigan says all her players take concussions very seriously, but especially Kleyer.

“Every year she is one of the first to inform the girls what a concussion is,” Flanigan said. “What we can do as a team, what to look for.”

Coach Flanigan wasn’t surprised it was Kleyer who stopped the game to get her teammate help, describing Kleyer as having a “natural ability to lead people on and off the field.”

Watch the University of Northern Iowa Women’s rugby team give the Team Up Against Concussions Speech:

Two of Kleyer’s own personal role models, Alev Kelter and Kate Zackary, are members of USA Rugby Women’s Eagles Sevens team. The Concussion Legacy Foundation is proud to partner with USA Rugby for the first ever USA Rugby Team Up Speak Up Week Sept. 8- 14, 2019. Members of the USA Rugby community can pledge to participate and learn more here.

Teams from every sport can participate in Team Up Against Concussions. Get started here.

Posted: June 13, 2019

As time went on, my headaches became rather unbearable and I could no longer tolerate gymnastics. So, 10 days after the initial incident, we went to the emergency room where it was confirmed that I did indeed have a concussion and could be at risk of developing Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). At that point we knew something more serious was going on than we thought and took all precautions.

With my headaches persisting and new sensitivities to light, sound, temperature and motion, I spent the next couple of months sleeping a lot, staying up in my room, and isolating myself from the outside world. I wasn’t quite sure what was going on, or what to do. We started to search for more doctors who could give us advice or guidance on treatments, as well as more information about concussions and PCS. Much of the time we got conflicting information and opposing advice. I started to realize not many people knew exactly what was going on in my brain, or what was causing my continued head and neck pain.

I had to miss starting high school for the first month, which is when you form most of your new friendships. I had a short period of time after seeing an acupuncturist when I felt better and returned to school, but the headaches soon returned. A few months after that, we were referred to a pain clinic as my headaches continued and I was medically deteriorating. We were hoping for a miracle.

The pain rehab program ended up doing much more harm than good because they did not understand PCS. The theory behind this program is to push through your pain, but it pushed me so far above my threshold that it ended up leaving me in a very bad place for a very long time. I had trouble just walking around school and got winded going up and down stairs. I spent most of the time at school in the nurses or guidance offices.

I was pushed not to leave school early, would only be allowed short breaks, and was strongly encouraged to take a computer technology class even when screen time was so difficult for me. As an athlete, I was used to being in the gym for many hours several days a week and learning to push through fears and pain on a regular basis. I could not understand why this recovery was so hard for me.

On the advice of the pain rehab program, I even went on a cross country flight to Hawaii as a “therapeutic” getaway. Neither I nor my family felt comfortable with the idea, but we tried anyway. With all the stimulation, decreased oxygen levels on the plane, crowds, loud noises, and lengthy plane ride it proved to be so far over my activity threshold that it sent me into a downward spiral that took me over a year to get out of. It was traumatic and not enjoyable at all. While there, my pain got so unbearable, that for the first time I felt truly hopeless and like I could no longer live this way.

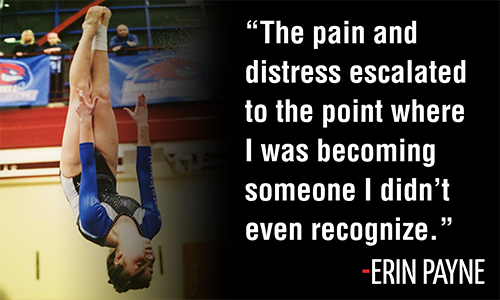

I spent the next several months in and out of school, with my pain still worsening. I tried several different medications, many of which had scary side effects that were even worse than my symptoms. We investigated a multitude of treatments and everything under the sun to try and get some relief, even post-traumatic stress therapies. Car rides made me sick, but staying home was isolating. There were times when I would scream out loud for help due to the pain and other times I would go into my basement and scream into a pillow. I would refuse to go near a TV or sounds, even music or people talking. I would refuse to leave the house. The pain and distress escalated to the point where I was becoming someone I didn’t even recognize.

I could not accept what was happening to me. I felt like no one could help me, none of the treatments were working, and every doctor would say to “give it time,” but I felt like I could barely make it through each day. It was an everyday battle fighting negative thoughts and trying to stay positive. I was angry and irritable at times, and for a while, I could not see a future for myself.

The more I went to school, the worse my headaches got. After a while it got to the point where I was present at school, but not participating. That’s when we decided I should stop going, and I ended up leaving my freshman year and completing the work at home in small doses over the summer. I missed out on the entire high school experience. My friends from home and the gym started to forget about me and my coach didn’t understand how my recovery could possibly be taking so long.

One night, I believe I got a gift from God. My mom and I were researching when we stumbled across the Concussion Legacy Foundation website, where we found stories of kids just like me. Before then, I had no idea that a concussion could last so long or be so severe. I was insistent that it couldn’t “just” be a concussion, and something more serious had to be going on.

The website had so much valuable information and we learned so much about what was happening to me, and that it was normal. It gave me a burst of hope. That’s also when we found Dr. Cantu. Thanks to Dr. Cantu, I was diagnosed with “dysautonomia,” a common PCS symptom that went unnoticed by several doctors. It helped to explain a lot of mysterious symptoms.

Dysautonomia is a term that describes what happens when your autonomic nervous system becomes dysregulated. This affected my heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature control and explained why I was having so much trouble with any physical activity. It also gave me flushing and burning of my face and hot and cold spells.

I had to be put on a Beta Blocker to control my blood pressure and use ice packs on my head, cheeks and even sometimes my feet to keep me cool! Since your brain controls all of your body functions, really anything can be affected by a concussion. I have also had issues with my endocrine system which controls hormones. My cortisol levels increased due to stress, which can contribute to weight gain and make other symptoms worse.

The truth about PCS is that there aren’t enough doctors, clinicians, coaches or parents that fully understand it. After discovering the Concussion Legacy Foundation website, Dr. Cantu, and the Headache Clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital, we could finally start the recovery process appropriately.

During this process I have celebrated 2 birthdays, missed most of freshman year and all of sophomore year. I have seen over 45 different doctors/ medical personnel, including four acupuncturists, six PT’s, five neurologists, one neurosurgeon, one hypnotist, five psychologists, one psychiatrist, four orthopedists, two cardiologists, one endocrinologist, one craniosacral therapist, four massage therapists, three pediatricians, three chiropractors, and two vision therapists. This does not include medical personnel from a few hospital stays! I have received nearly 200 various painful injections (not including acupuncture which does not hurt!) to my forehead, head, temples, neck, shoulders, and the bridge of my nose.

And finally, the good news. About a year after my injury, my headaches started to get less severe. It appeared the treatments were helping. That was my turning point. And then, a few months later, what really pushed me over the edge in my recovery was when I began seeing a Manual Physical Therapist. He was able to feel things that do not appear on any MRI. He was able to gently correct a misalignment of my skull and neck joints that no one else had discovered. I am now a year and a half post injury and feeling better every day. I still have a long road ahead to achieve full recovery and return to school and sports, but I can finally see the finish line and I want others to know that it can happen for them too!

My best advice for anyone going through this is to keep trying until you find something that works for you, never give up hope, and always trust and follow your instincts. You may need to stretch out of your comfort zone but don’t push yourself too hard. Seeking out others who know what you are experiencing is important. Whatever your faith is, don’t stop believing, even if you have moments of doubt. I received over 100 cards, letters and gifts from family, friends and a nation-wide prayer group which was a big comfort. PCS can be overcome and now my focus is on helping as many other people as possible.