Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

I would never, in a million years, have thought a decade of repetitive head impacts could cause a neurodegenerative disease in a 32-year-old female. Trust me, if it wasn’t personally happening to me, I wouldn’t believe it. But it is, and my brain is dying before my very eyes. It is heartbreaking for my husband Andrew to witness. I am lucky to have his unconditional love, his understanding, and his unwavering support.

I share all of this publicly with complete transparency for the sake of CTE awareness, so when I am diagnosed with CTE postmortem, these words will be here to provide an account of what it’s like to live with this disease, in hopes we can prevent it. If I can’t turn my suffering into something meaningful — into something positive — then what is the point? My only wish in life is to alleviate the suffering of others, and I hope that my attempts to shed light on this horrendous disease will help to do just that.

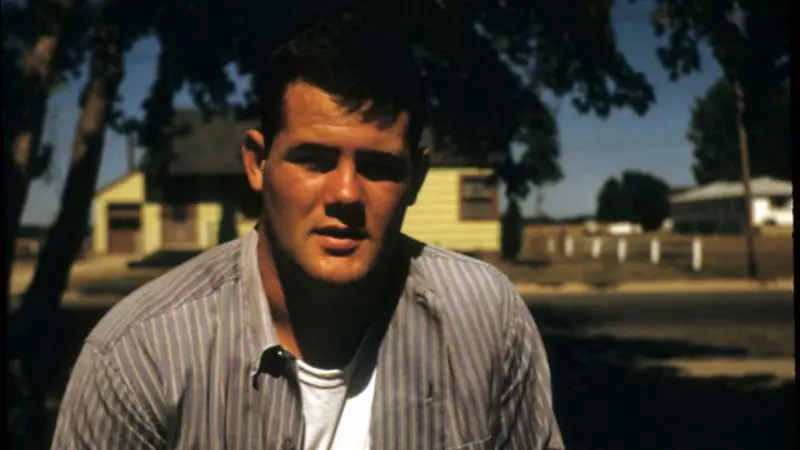

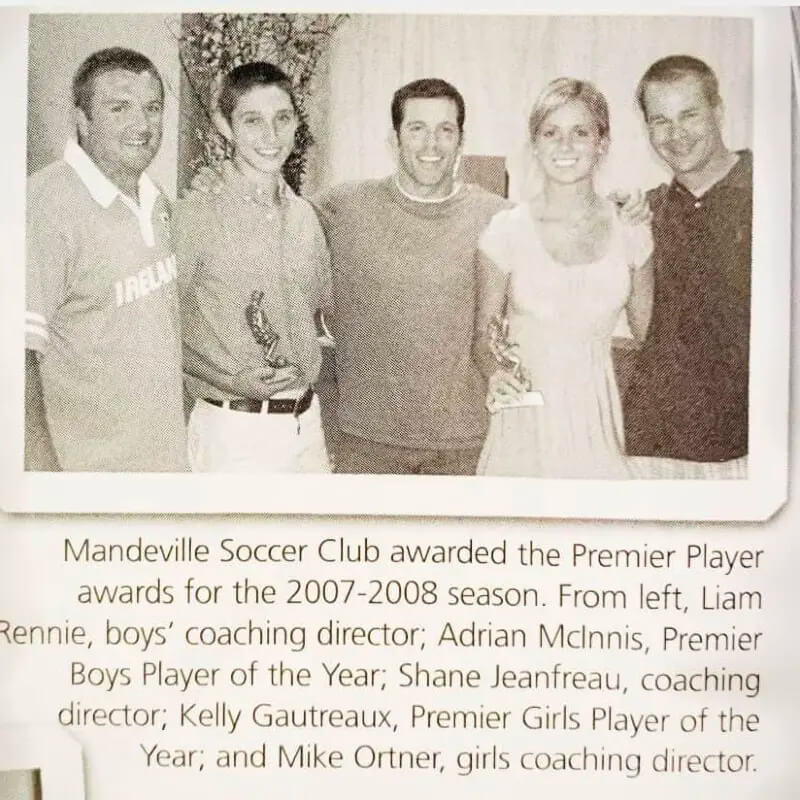

I started playing soccer and heading the ball at 6 years old. By the time I was 9, I already knew what I wanted to be when I grew up: a professional soccer player and a doctor. As I got older, my passion for soccer and my love for science only grew. Like most athletes, I was extremely competitive, driven, and goal-oriented. I was also willing to play through anything. My pain tolerance was through the roof, and I had an innate desire to excel at everything. I once somehow played half of a game with a broken collarbone because I didn’t want to sit out. By halftime, I walked off the field and finally went to the ER.

Between playing soccer for a club, my school, and the US Youth Soccer Olympic Development Program, I was involved in the sport practically year-round from age 8 to 18. I earned a scholarship offer to play at Louisiana State University, which I officially signed as a high school senior. I lettered my freshman year but only got playing time in seven games my true freshman season. This was not enough for me. After the season concluded, I wanted to transfer to another D1 school where I could make an immediate impact on the field. I went on official visits to Appalachian State and College of Charleston, accepting an offer from the latter. It was truly the perfect-sized program for me, and I was able to secure a starting spot as a center midfielder in the fall of 2010, my sophomore year. But after playing through a series of concussions that season, I was never cleared to play soccer again.

My first diagnosed concussion was not until I was 19 years old. I have no idea how many undiagnosed concussions I sustained over the years. My parents can remember tournaments where I took significant hits, but I always eventually got up and kept playing. We never thought anything of these hits, and we definitely didn’t realize something as seemingly minor as heading a soccer ball could have any long-term neurological consequences.

In hindsight, the first sign something was wrong with my brain was the excessive, inappropriate weeping — and my inability to stop it. I had no clue this was a concussion symptom. No one ever told me, so how could I have known? At the time, most doctors didn’t think the two were related.

I couldn’t lie this time and say I felt OK enough to play. I couldn’t even get a word out between the profuse sobbing. So, I was finally forced to sit out, officially in concussion protocol. No school, no contact, no running, strict rest. Being a stubborn athlete, I was secretly running and training the entire time. In my defense, I didn’t know there would be a cumulative effect to my brain and that the symptoms could or would be permanent. I thought the pain of pushing through these concussions would be fleeting. I certainly didn’t realize it could mean my symptoms would be persistent. I also didn’t realize the number of repetitive impacts I was taking would put me at risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease.

I also suffered from cognitive deficits, making it nearly impossible for me to finish my undergraduate degree. It took the next six years to finish my last four remaining academic semesters. Before my concussions, school was always easy for me. I was a pre-med biology major with a 4.0 GPA. After my concussions, simply sitting through a three-hour science lab was absolute torture. I could not function like before and had to drastically reduce my course load. I swapped out medical school for a more realistic goal of becoming a nurse practitioner. Still, I was determined to fully recover, get my old brain back, and live life on my own terms.

Along with the cognitive deficits and crying spells came the suicidal depression. It’s worth noting that prior to my concussions, I did not even believe in mental illness. I thought depression was circumstantial and people who claimed to suffer from it were simply making excuses. In a matter of months, I went from not even believing in mental illness to experiencing depression so severe I was barely clinging to life.

To this day, the suicidal depression remains the most difficult for me. I am fortunate antidepressants work for me, because I don’t think I could survive otherwise. Admitting this doesn’t make me weak; it makes me honest about the damage to my brain. I attempted suicide twice in my early 20s, when I was still drinking alcohol. I quickly learned alcohol and my brain do not mix well anymore.

It wasn’t just the suicidality that worsened, but also the rage. By my mid-20s, fits of rage started popping up more and more. I had been dealing with suicidality and other post-concussion symptoms for about five years when the rage began. I also became increasingly sensitive to alcohol, and one beer actually made me attack and bite another person like a wild animal when I was 27. I have not touched alcohol since. These rage episodes are scary enough when I am sober; adding alcohol to the mix is like throwing gasoline on a fire.

I’m not sure when it became evident to my family and I that this was not just PCS anymore, but something much more serious. These events over the years made it obvious my brain was getting worse, and we might be looking at a whole different beast: probable CTE. One thing you must know about my story is I always assumed I would make a full recovery from my college soccer concussions. I wasn’t resigning myself to the fact that I probably have CTE and giving up. Three months of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, countless neurorehabilitation stints — vestibular rehab, cognitive therapy, you name it. I tried everything in the books for a decade.

While working towards my goal of becoming a psychiatric mental health nurse, I took a job in the behavioral healthcare field after earning my degree in 2016. Then, only six months in, I was assaulted by a patient. I have no memory of the event, but I was jumped and tackled to the floor, dragged across the floor by my hair, and kicked and punched repeatedly in the head. This, after sustaining a serious concussion (again, on the job due to a patient assault) three weeks prior. Both of these incidents were devastating. I had just moved to Nashville and worked so hard to bounce back from my career-ending concussions sustained during college soccer. Years of post-concussion symptoms meant spending most days confined to a dark room battling suicidal ideation, debilitating migraines, extreme sensitivity to noise and light, and disabling cognitive deficits. But I persevered and completed my degree, got engaged, and planned to enroll in Vanderbilt’s accelerated BSN program.

Unfortunately, the concussions I sustained while working in behavioral healthcare made my symptoms worse. I can no longer hold down a job at all. But here’s the thing — my brain was already worsening before these concussions. My fine motor skills were deteriorating and the cognitive deficits I dealt with were not getting better. My suicidal depression also kept getting worse, requiring higher doses of the antidepressant that works for me. The concussions from work were simply the final straw.

Please take concussions and CTE prevention seriously. The scariest part about having probable CTE is neurobehavioral dysregulation. It leads to violent behavior with no basis in reality. I’m not sure if there is anything more terrifying than witnessing yourself fly off the handle, screaming at the top of your lungs, physically violent, filled with rage and suicidality, all while being completely unable to regulate it. This disease makes one a monster at times. Andrew has learned to spot the signs — the dead look in my eyes, the irrational anger, the terror. It is partially traumatizing for him to see me in these states, but I am grateful to have someone that loves me through this disease and can see and appreciate when the real “Kelly” is present.

As my probable CTE progresses, I also have days where I am not “here” mentally. Andrew says he can tell whenever I’m absent. “It’s like you’re not really there; you’re not behind your eyes. You’re completely gone,” he says to me through tears. “I just miss my Kelly, that’s all.” He is right. I am cold, empty. My expression is flat. The life behind my voice is gone. I can’t even think. I feel like the walking dead. I have no idea where I’ve gone. All I know is that I’m not here.

These types of days, filled with vacant eyes and blank stares, are popping up more frequently. I am sad for my husband and how he has to witness my mind and personality deteriorate in front of him. I don’t think this is how he pictured our 30s. He has to cope with little losses of me on a daily basis. Degenerative brain diseases like CTE are devastating for the entire family. I am not ready and don’t want to fade away, but I will try to embrace this next chapter with grace and dignity as I hold on to myself with all I can.

For the past 13 years, what I originally viewed as a journey of recovery has gradually shifted to one of acceptance. I have found the most solace and comfort by being brutally honest about my situation and accepting my brain and this disease for what it is.

Fortunately, there are some treatments that have helped. Medical marijuana specifically has improved my quality of life tremendously these past three years. It keeps me present when I appear to have that lifeless look in my eyes. It also helps with sensory overload, fits of rage, and my suicidal depression. I’ve also found a medication which regulates my behavior. It not only prevents the random inappropriate weeping, but has eliminated so much of my anger episodes. Last but not least, the antidepressant sertraline has been a lifesaver.

In addition to neurobehavioral medication, I lean heavily on my support system. My family fully supports me and understands CTE. They have been with me on this journey every step of the way. I am forever grateful for these amazing human beings whose love has often been the catalyst and motivator for me to hold on and endure. I’ve learned over the years that support can come in many forms. My dogs often help me get out of bed on days where I do not have the strength or willpower to do so myself. I have found myself reaching out to the Concussion Legacy Foundation through their CLF HelpLine (thanks guys!) more times than I can count over the past 13 years. Please know that you are never, ever alone.

It’s important to know even if all your support systems seem to fail, you are stronger than you realize. If I can survive this, so can you. I know it can feel overwhelming when the darkness hits. I know it’s impossible to feel even a sliver of hope things will ever get better. You need to remember the only constant is change; that these feelings will pass, and that you will be reminded again life is worth living. I have been at rock bottom a million times, my brain yearning for death by my own hand, but I have learned to find the light in the darkest recesses of my mind. And if there is no light to be found, I tell myself my brain is playing tricks on me, and that to give in to the suicidal depression would mean CTE wins. I am competitive and will never let CTE win. So, I press on, and so will you! Just remember, never stop reaching out to others when you are depressed. None of us can get through it alone.

The thought of potentially alleviating at least one person’s suffering by donating my brain to CLF to support CTE research is what keeps me going and makes all this suffering worth enduring. I can’t think of a better legacy than to help contribute to research so no other athlete or veteran has to deal with what I and so many others have experienced.

Finally, my heart goes out to all those who suffered from CTE and ultimately took their own lives. I know how hard it is to have absolutely no control over the torture your own mind is inflicting on you. I know how hard it is to choose life when your brain is telling you to choose death. Rest In Peace. Your legacies live on.