Posted: August 5, 2020

Concussion. A word I don’t want to say for the rest of my life. But that’s just not the case, because I’m about to say “concussion” a whole lot in this story. I wouldn’t wish a concussion on my worst enemy… well maybe my WORST, worst enemy…

So how did I get my concussion? It was September 2019. Yes, September, as in nine months ago! I went to a theme park I’ve never been to with the intent of having a jolly ole time, but unfortunately it didn’t end up that way. After having a few snacks and riding some rides, my boyfriend Frank and I decided to go on this interesting looking roller coaster. It looked different, but I didn’t think much of it. I looked at the safety warnings, and they were no different than any other roller coaster I’ve been on.

We got on the roller coaster, strapped in, got the over the shoulders seat secured, and the ride began. The coaster started out normally and went up for the drop. It dropped, and immediately went directly back up and BOOM my head and neck thrash back causing my head to hit VERY hard against the headrest. I felt an immediate blow to my skull, with an intense sense of pain right away. I wanted to get off the ride immediately, but unfortunately this was only the beginning. The whiplash motion happened a few more times, each time my head slamming against the headrest. After the last drop, which was the highest drop of all, the roller coaster took a few rough upside-down turns, slamming my head even more, and at the last loop, we remained upside down for a few seconds. Fun, right?

So, the ride finally came to an end, and I got off and immediately felt like a huge bag of sh%t! I was nauseous, dizzy, and obviously in a ton of pain. I took a seat to rest for a while. I put ice cubes on my head, neck, and body to kind of wake myself up (I didn’t pass out, I just felt extreme fatigue like I wanted to go to sleep). It never occurred to me this could possibly be a concussion. I had never had a concussion before so it didn’t cross my mind that a roller coaster could cause a brain injury.

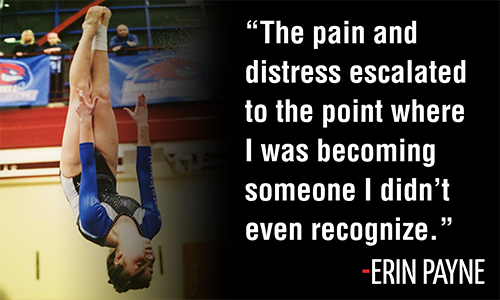

Frank took this picture moments after I hit my head:

This picture where I look sad, angry, and in pain is exactly how I was feeling. And yes, those are tears forming in my eyes. To be honest, I don’t remember much of the day after this. The next day, Frank and I had plans to fly out to LA to film a quick project. I woke up that morning feeling like absolute crap, but we stuck with our plans because I thought the pain would pass. On our ride to the airport, I felt extremely nauseous, like I was about to throw up. I honestly thought I was feeling this way because I ate junk food the day before, but looking back, I was clearly feeling nauseous because I had a brain injury.

Days went by, and I still had a horrible headache. Weeks passed, I still had a horrible headache. A month went by, and surprise, I still had a horrible headache. It wasn’t until my older brother, Dewey, told me I could possibly have a concussion. At this point, about a month after my head injury, it still never crossed my mind that I could even possibly have a concussion. When I think of suffering a concussion, I think of being in a car accident or being punched in the face or getting knocked out or being thrown off a Hell in a Cell… not riding a roller coaster. I’ve been riding the biggest, tallest, most intense roller coasters across the country since I was in first grade (yes, I was tall enough even at 6 years old). Over the past 20 years I’ve ridden hundreds, if not thousands, of roller coasters and I have never had any type of issue or injury.

Right after Dewey told me about the possibility of a concussion, I did a simple Google search and it turned out I had almost every single symptom of a concussion. I finally got an appointment to get my head checked out. Right away, the doctor confirmed it was a concussion and ordered physical therapy sessions and also ordered an X-ray of my neck because the doctor could feel my neck was very stiff. The X-ray came back that the cervical spine in my neck was curved backwards, most likely as a result of the whiplash of the roller coaster.

I can count on one hand how many times I’ve driven at night in the past nine months. And when I’m in the car at night, with someone else driving, I have to wear sunglasses and completely cover my face with a jacket, blanket, or hat. As far as sounds, it feels like I have the hearing of an owl (fun fact- owls can hear the heartbeat of the mouse 400m away). Well maybe my hearing isn’t that intense, but it is still super-dee-duper sensitive. From the vacuum, to the TV, to my little brother talking too loudly, to my dogs barking, sometimes it feels impossible to escape the sounds. So that’s why I have earplugs next to me at all times so I can just pop them in if the noises are too overwhelming.

The back of my head is still extremely sensitive to touch. Even when I’m trying to go to sleep, it hurts to put my head on the pillow, so I have to readjust a lot to find a way for my head to be comfortable. Also, every time I’ve been in the car, I have not let my head even touch the headrest, just in case we hit a bump or hit the brakes a little too hard. I just cannot risk my head even being slightly hit. I’m scarred from headrests, literally.

Aside from the obvious pain that comes with concussions, I’ve also been suffering mentally and emotionally. In simple terms, I’ve been a mess. Not a hot mess, not a cute mess, just a straight up MESS. Basically, every single one of my emotions has been heightened and amplified. I’ve been through periods of depression throughout this whole concussion journey. I’ve had mental breakdowns, meltdowns and panic attacks; some of which happened in public.

One of the very last times I was in public, before the pandemic, Frank and I went out to this nice restaurant for dinner. They sat us at a really nice table, but it was right under a bright light, so we had to move tables. We sat down again at a dimmer lit table and as we were looking at our menus, a big party sat down next to us. Right away they started taking pictures with flash! My mortal enemy! And by the fourth flash I internally started to freak out. I grabbed my stuff, told the waiter I have to leave (he was very confused) and I essentially ran out of the restaurant leaving Frank behind. And then I let it all out in the stairway (my tears). It really sucks because everywhere I go, I have to be on alert of bright lights and loud sounds, even at places like restaurants. This certainly wasn’t the first time I had to leave something because of lights, cameras, or loud noises. Do you know where it happened a lot? The Disney Cruise I just went on a few months ago.

I booked a Disney cruise back in October, one month after my concussion. After a little research, I found that most concussions last one to two months, tops! On average, concussion symptoms typically last only a few weeks. The cruise was booked for the end of February and I thought “There is NO way I could possibly still have concussion symptoms by then.” Boy was I wrong!

I was looking forward to this cruise so much! I’m a huge Disney fan, and I haven’t been on a Disney cruise since I was in middle school, so I was just really excited to feel happy for once… but it did not turn out that way. The morning of the cruise, I was feeling horrific; even worse than normal. Most likely due to a few restless nights before. Basically, sleep is the only thing that helps me, and if I don’t get enough sleep, it’s going to be a very, very bad day.

We get on the cruise, walk around for a little, eat some lunch, and all I want to do is lay down, even on this gorgeous cruise ship. I felt so horrible that I missed dinners, shows, and even the Pirates of the Caribbean dance party. I basically missed every fun activity on the cruise ship because my head could not tolerate the pain and I was internally miserable (despite what my Instagram looked like). Most of my Instagram pictures in the past nine months have either been throwback pictures or me just putting on a fake smile.

Here is what I actually looked like on the cruise:

It is a very scary thing how much pain a smile can hide. Not just in pictures, but in real life too. I put on a smile for other people when the last thing I wanted to do was smile. I just don’t like to be a downer or bring down the mood of others, especially while on vacation. I do feel bad for Frank because he missed out on all the fun activities of the cruise because he mostly stayed with me.

In the beginning of my concussion journey, I could barely talk or smile because I was in so much pain and it was honestly exhausting to put much energy into something as simple as grinning and speaking. Over time, I got better at talking and smiling, not because I was feeling better, but because I got better at hiding it. The average person would never suspect I was in so much pain underneath my smile.

So that’s how my concussion has been going. I’ve been trying several different treatments for my head, but nothing seems to actually help. I’ve tried physical therapy, acupuncture, electrotherapy, cupping, breathing exercises, extremely deep neck massages to help break up the pressure in my neck, flotation tanks, SOS manual therapy, herbal medicines, eating healthy, and taking supplements.

I’ve also been resting a ton; I was self-quarantining even before this pandemic, despite it looking like I’m living my best life on Instagram. I didn’t leave my house or wash my face for three weeks in January. That was where I was at, just no motivation for anything. I’ve cut down screen time on my phone and computer, I stopped emailing companies, which has made me lose a lot of work. I’ve cancelled fun plans and trips. I haven’t been able to work out in nine months because it makes me feel even worse. I’ve basically stopped life. And I’m sure a lot of you are feeling the same way right about now because of the current situation of our world. I want to continue to try out other treatments, even the most outlandish ones, but it’s been hard the last few months with places being shut down, and I don’t want to put myself (or my family) at risk if I were to go to clinics that are open. I’ve recently been trying to manage the pain with monthly migraine prevention injections. They hurt way worse than any other shot I’ve had, and I have to do the shot myself. Some days it helps, other days it doesn’t… at all.

There are a few reasons why my concussion symptoms are lasting so long. One doctor told me that I could have sustained multiple concussions, a cluster of concussions, while riding the roller coaster. Each time my head slammed on the headrest could’ve been a new concussion. Another reason could be because of the curve in my cervical spine being backwards, therefore putting extra pressure on my neck, not allowing enough circulation and blood flow to go to my brain. I have been trying out different ways and supplements to increase blood flow to see if anything helps.

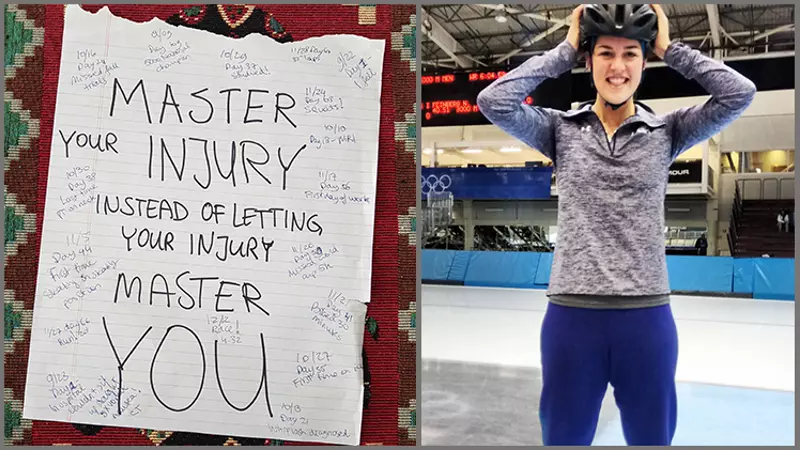

I recently spoke on the phone with Olympic Speed Skater, Carlijn Schoutens, who also suffered from Post-Concussion Syndrome for nearly a year. It was really nice to talk to someone who shared some of my exact struggles and knew exactly what I was going through. It definitely helps to speak to someone who has been in a similar position. I know what you’re probably thinking right now… “what about your dad?” While my dad has suffered many concussions throughout his wrestling career, he said none of his concussions ever lasted this long. It’s hard for him to give it advice other than just rest and take it easy, but he did connect me with Chris Nowinski, Ph.D. who is the CEO of Concussion Legacy Foundation, and he helped me find the correct clinics and doctors to go to.

Not only has this concussion affected my life, it’s affected my family and loved ones’ lives too. I can tell my family is super annoyed by me and my concussion. They say they have to live their life under Noelle’s rules… which is kind of true! Noelle’s rules include: no bright lights! If they turn on any lights, they have to let me know before so I can take cover and close my eyes, and same goes with turning off lights. No loud noises, so they need to keep their voices low, keep the TV low, and prevent my dogs from barking at all costs. Sometimes they have to help me take food out from the fridge because the fridge lights are way too bright for me.

I cannot wait until the day where I can be headache free and not force a smile and drive at night, and take pictures with the flash on, and just be happy. All these things I’ve taken for granted my whole life. I really cannot wait until all the pain is gone, because this is truly ruining my life.

Every day is different for me. Some days I’m OK, and some days I feel like I got hit by a train. Some days I feel completely defeated by my concussion, but I still have hope that there are better days ahead. And if you’re reading this and you are also suffering from a concussion or anything else going on in your life, just know that things will eventually get better, even if it takes a long time. You just have to stick with it and think positive thoughts, and not give up!

If you’re interested in being connected with a mentor like Noelle was with Carlijin, if you need help finding a doctor, or if you want to learn about evidence-based treatment options for your symptoms you can submit a request to the CLF HelpLine. A dedicated staff member will point you toward resources to help in your recovery.