Posted: May 25, 2018

My story

On December 15, 2015, I hit my head on the granite counter top while picking up my homework off the kitchen floor. There was an immediate onset of headaches. After a couple of days visiting the school nurse, it was determined I may have a concussion and should see my doctor. What started out as a likely concussion escalated over time to much more. Eventually, I would end up seeing some of the best doctors the world has to offer at both The Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center and Boston Children’s Hospital.

My health significantly deteriorated between December 2015 and March 2016 with no real known explanation other than the concussion. School, work, and activities were stripped away, school days were reduced, and homework was no longer an option, yet my health continued to worsen. Following a visit to my Ophthalmologist at the end of March 2016, he found significant swelling of the optic nerve and fluid-filled optic discs, further launching a myriad of testing. It wasn’t until early April 2016 when my growing medical team found a blood clot at the base of my sagittal sinus vein. To quote one of my physicians, “it was the perfect storm”: a concussion, high intracranial pressure and a blood clot.” Said another way, “it’s complicated”, a term that I have become all too familiar with. I was hospitalized in April 2016 to address the blot clot and pain management. I did not attend school from April – June, missing out on my last year of elementary school and all the fun activities that went along with it. During this time, I remained in significant pain. In addition, I lost my balance forcing me to walk with a cane, spent many hours enduring tests and sitting in doctor offices, attended physical therapy several times a week, participated in alternative treatment options, was tutored to get caught up on missed academics and somehow managed to get through each day, using the mailbox of cards and acts of kindness from friends and strangers as my beacon of hope. Not to mention, I did try to enjoy a daily dose of the Ellen DeGeneres show, along with my sisters, to make me laugh. It usually worked. “Hope” was, and is, a word we use daily. I received fantastic news at the end of August 2016 when the blood clot had dissipated, my balance returned and I was able to return to school as a proud middle-schooler in September 2016.

Although the blood clot cleared, there are lingering medical issues that remain, with the most prevalent long-term side effect of a constant headache and chronic fatigue resulting from high intracranial hypertension and post concussive syndrome. Neither can be seen to the eye, but are part of the hidden illness that have never gone away.

After meeting with many doctors at The Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center and The Brain Injury Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, I was encouraged to get involved with something that would help replace what I have lost in terms of my participation in activities I once loved, e.g. contact sports and related activities, and to help with the associated psychological impact. After one of my many physicians had learned of my 2016 philanthropy efforts of donating my birthday money in the form of gift cards to the Hematology Clinic at Tufts, I was encouraged to move forward with the Mighty Meredith Project. Therefore, after months of discussing the purpose and potential charitable offerings, together with my parents, we decided on the following mission for the Mighty Meredith Project:

• Bring education and awareness to having a Traumatic Brain Injury as an adolescent, with specific attention on their hidden impact – both physical and psychological.

• An avenue to give back to the medical community involved in my care, both past and present and support TBI research.

• Promote kindness, especially to those who may have a “hidden injury or illness.”

Presently, my recovery is slow and sometimes stymied by complications from the TBI. While I am able to attend school and participate in activities such as Student Council and re-defining my new “normal” through the world of dance, philanthropy and the advent of the Mighty Meredith Project; some things will always remain off limits and my life has been forever altered with one hit of the head. The hope for the Mighty Meredith Project is to bring a bit of hope, joy and education to as many people as we can and to let traumatic brain injury suffers there is a network of us willing to help at any time.

Interview with Mighty Meredith

If there’s one thing you’d want everyone with TBI to know, what would it be?

You’re not alone.

You had to adjust to a “new normal.” What are some of the adjustments you have had to make?

I used to play lots of sports but I can no longer play any sports for the rest of my life. I can’t ski, I can’t sled. I can only dance. And that was a big one because I used to play soccer, basketball, lacrosse, everything. And now it’s just dance.

Concussions are an “Invisible injury.” Was that one of the most difficult things about it?

Yeah. It was one of the most difficult things because I would go to school and do my homework but people only saw me at school, they didn’t see me go home, go to bed, cry because of the pain. I would go to school and seem fine. Also, living with a headache constantly was hard. People would usually think, ‘a concussion! Big whoop.’ Not really- it is a lot more than that. I have lost a couple friends from this, because they thought I was lying or exaggerating for attention.

What was most important to you when you started the Mighty Meredith project?

I love being kind. I love seeing people smile when I do something nice for them. That was a big part of it. Another part of it was raising awareness for traumatic brain injuries.

What is your main goal with the Mighty Meredith Project?

I think I want everyone to understand what it is like. I don’t want them to have to go through it but I want everyone to understand what it is like to live with a hidden illness. I want everyone to be kind to one another because you never know what is going on behind the scenes.

Are there any short-term goals for Mighty Meredith project? What do you have planned this summer?

We did a bake sale last year. We are doing another one this year. What I, personally, really want to do… when I was sick… I would watch Ellen every day, and I have always wanted to be on the Ellen Show.

How does it feel, knowing that you are other people’s strength as Mighty Meredith?

It is nerve wracking, but it is also feels really good. When I was sick, I didn’t really have anyone I could look up to who’d been through this. I was just kinda figuring it out by myself. If I did have someone, I think it would be a lot easier. Now that people can see me and see that they are not alone and that they have someone that knows what they are going through. It’s good.

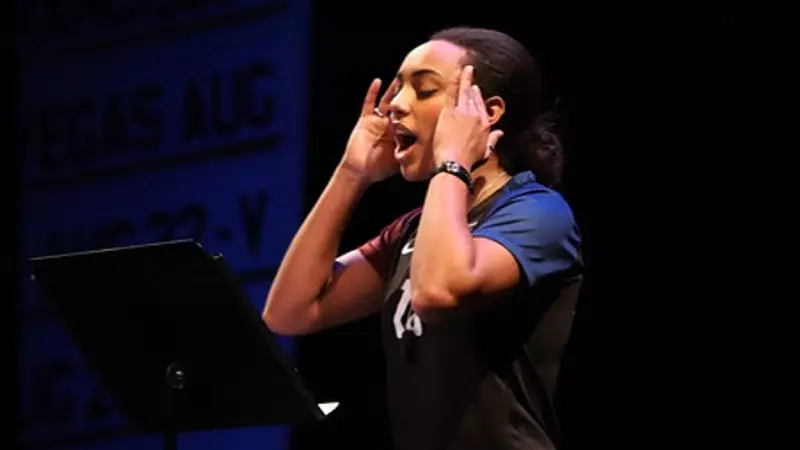

Was there one specific talk that made you step back and realize, whoa this is something?

I have done a couple. Some with local Daisy-Brownie troops, one with the student council at the high school. But there was one, at a local gym in town, after the fundraiser was over, I stood up and spoke and everyone started to cry. And I realized then, that this is big and this is what I want to do. It’s cool.

What was it like to meet Chris Nowinski and the CLF staff?

I have wanted to meet Chris Nowinski ever since I heard about the CLF and what he was doing to help others with TBI’s and raising awareness of concussions. I thought our scheduled meeting would just be involving Chris, my mother and I. I then turned the corner and it was like I was a celebrity walking the red carpet. The entire staff of the CLF was right in front of me. My heart was pounding with joy and my mouth hurt from smiling so much. The fact that the entire team took time out of their busy day to meet with me made me feel overwhelmed with love. That was the best day ever! Thank you to all the CLF staff for meeting with me, and to Chris for making me, a girl who once struggled with finding her new normal, feel like I was a part of something big.