Raymond Davies

Hector Ortiz

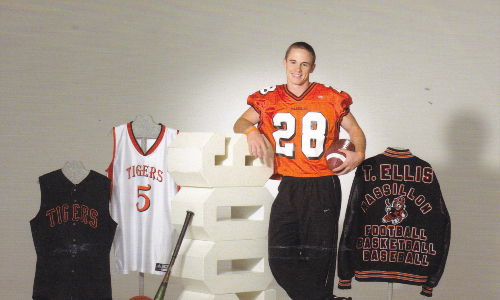

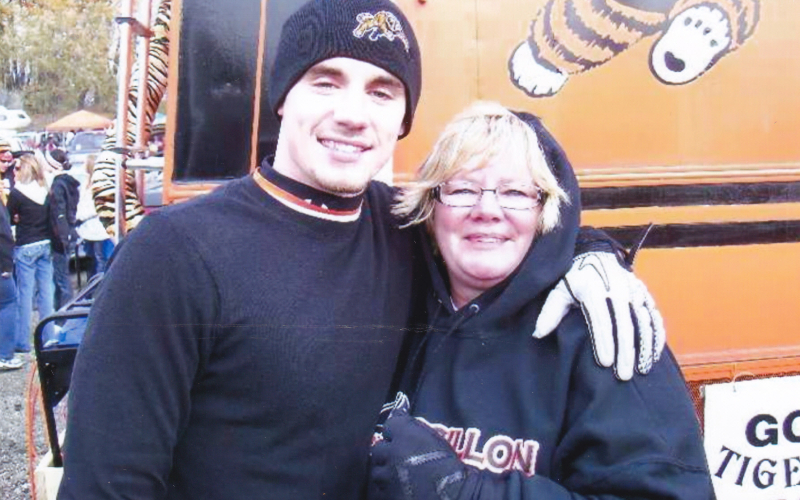

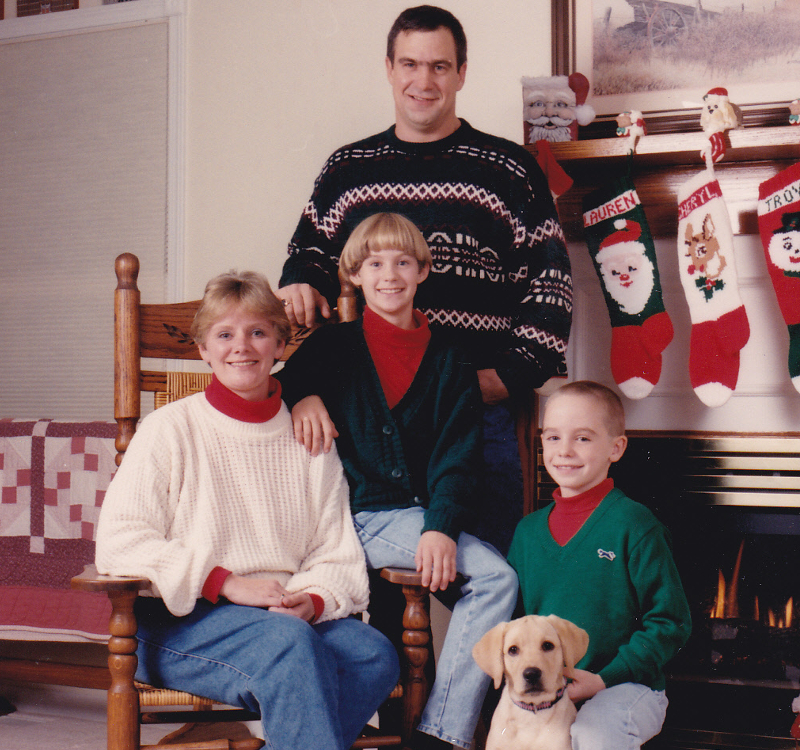

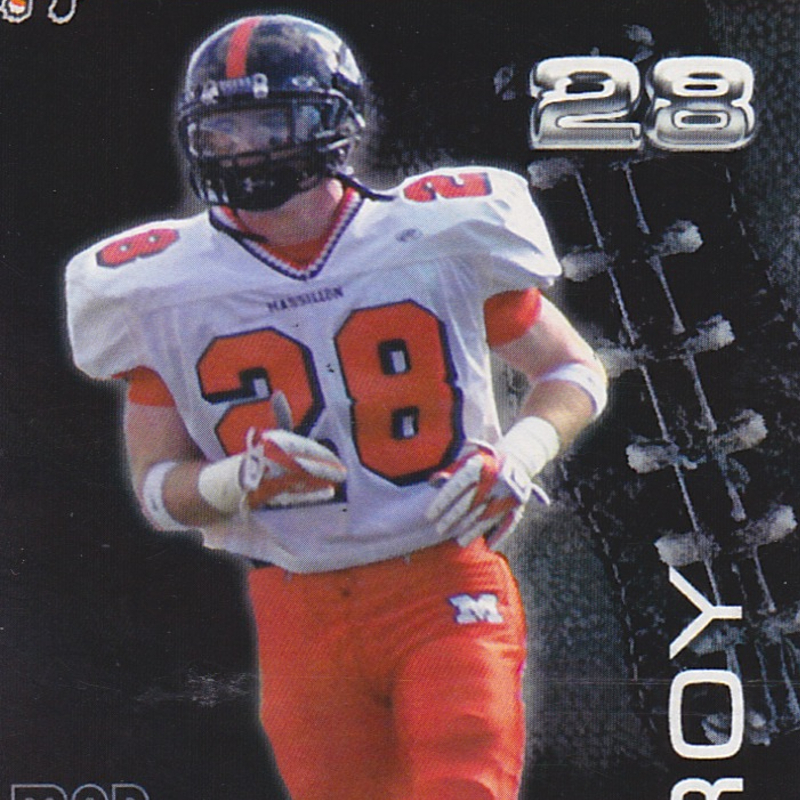

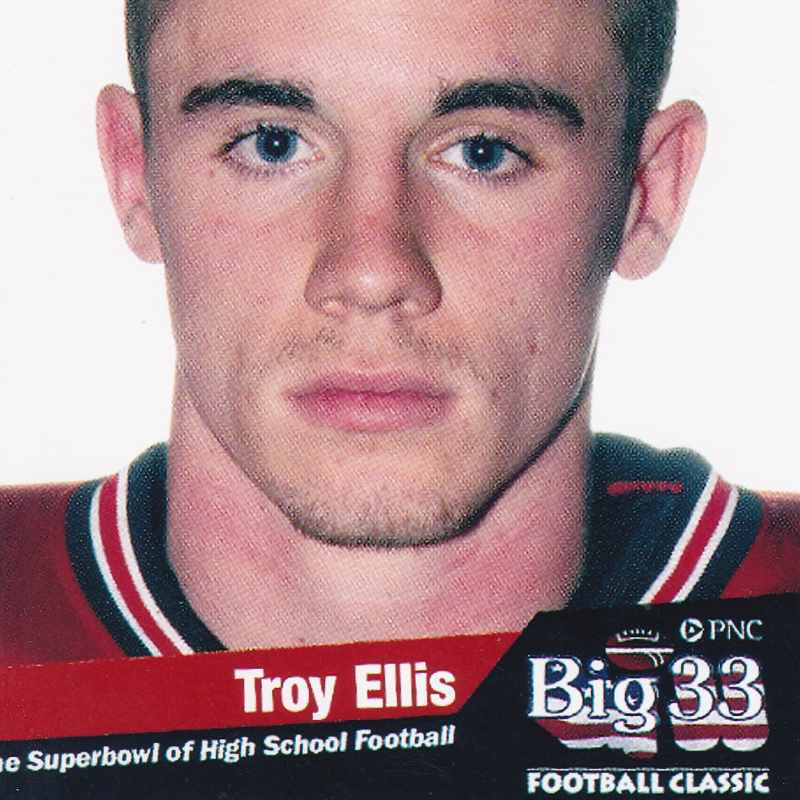

Troy Ellis

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Troy Ellis had a big presence and an infectious personality. He was very handsome and charismatic. The boy could dance too, and he was the life of the party. He was often told how much he looked like Channing Tatum. Troy thought he could play Channing’s younger brother in a movie. He would say, “If I was given a dollar for every time someone told me I looked like Channing, I’d be a millionaire.” He was fun, energetic, lovable, and loved by many. He recited lines from movies on a regular basis, especially from the movie Forrest Gump, which always produced lots of laughs.

Troy Boy was a natural athlete, showing his abilities very early on in his life. He couldn’t even walk yet but was always reaching for a ball of some sort. When he was two years old, he received a baseball and glove as gifts. He slept with them and called it his “glub.” His older sister, Lauren, was also very athletic. I knew, as well as their father, that we were going to spend a great deal of our lives watching them play sports. They were talented and eager to compete. They made each other better and there were fights along the way. Both were voted “Most Athletic” by their peers in high school. His sister was his hero. Troy was Lauren’s best person and stood up for her when she was married.

Troy played soccer, basketball, baseball, and of course, football, which he started in the fifth grade. He played for the storied Massillon Tigers in Massillon, Ohio. Football is close to godliness in Massillon. Troy loved the game. You are somebody when you are a Massillon Tiger. Little kids looked up to him and wanted his autograph. He was a three-year starter and never missed a game, playing cornerback, wide receiver, and punt returner. He was second team All-Ohio his senior year and was on the All-Stark County Team. He played in the Big 33 game in Hershey, Pennsylvania in 2006. He was a one-man highlight reel his senior year against Cincinnati Elder at the Cincinnati Bengals stadium. He had five interceptions in this one game (a record for the Massillon Tigers) while also recovering a fumble and returning it for a touchdown. He was named the game’s MVP.

Troy was known as a hard hitter and received the Bob Cummings Hardnose Award his senior year as voted on by members of the Massillon Tiger Booster Club. Former NFL player Chris Spielman also won the same award in the past. Troy received many accolades in the sports he played and he earned them all.

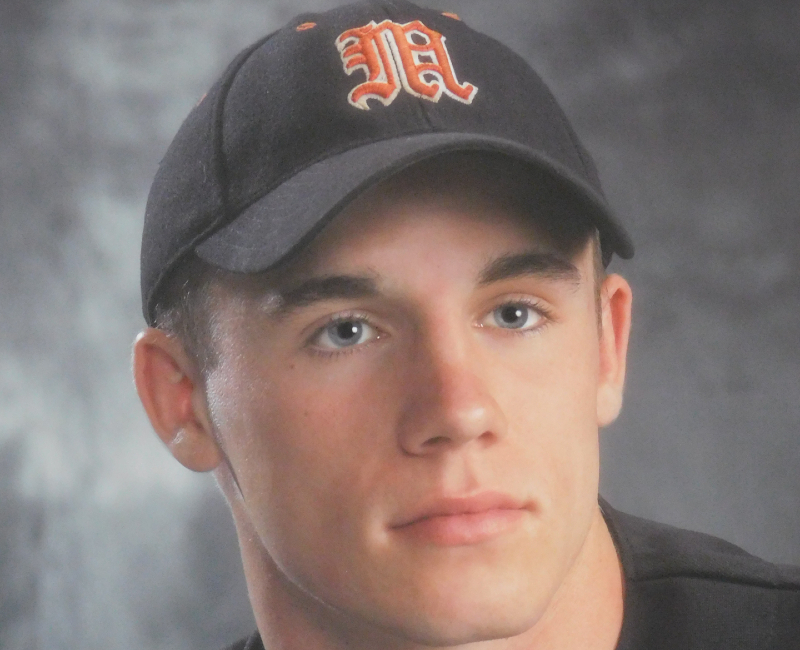

As his mother, I always thought baseball was Troy’s best sport. He was a four-year varsity starter in high school, the first at Massillon since 1975. He played second base and then shortstop. He played for the Stark County Stars in summer ball. A local reporter said, “Troy is the epitome of a leadoff hitter.” He went on to play shortstop at a junior college, Olney Central College in Illinois, for two years. While at Olney, he played a game at Busch Stadium. He also played Class A ball in Kentucky and played for the Canton Terriers.

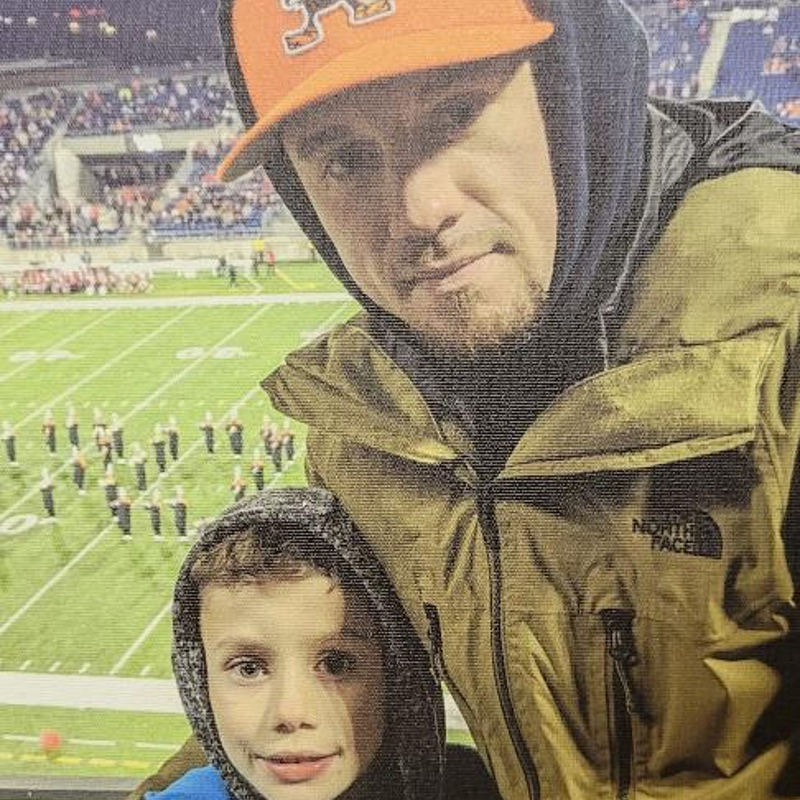

Troy had a son, Ashton, who was 10 at the time of Troy’s death. Troy and Ashton’s mother were no longer together, but he would get Ashton nearly every weekend. He enjoyed teaching him about baseball, football, and basketball. He installed a basketball hoop in his basement for Ashton. They would go fishing, golfing, roller skating, and played laser tag. He also shared his love of music and dancing with his son. Several years ago, Troy bought Ashton a pair of LeBron’s shoes in a large size that he has yet to grow into.

Troy was employed as a third generation plumber and pipefitter out of Local 94 in Canton, Ohio. His coworkers loved working with him. He also helped coach a middle school girls’ basketball team and was often known to lend a helping hand to others.

Troy had multiple head traumas from a young age. He fell out of a wagon and hit the back of his head on the cement floor. He fell off the side of the basement steps. He rode his bike down the deck steps. The front wheel came off of his bike and he fell face first into the sidewalk. The worst head injury was when he fell out of a tree at age eight and had a brain bleed. That was the worst day of my life, until the day he died. He was in the ICU for three days and in the hospital for a week. In time, he recovered and was cleared to continue playing sports. Additionally, he took a nasty pitch to the left side of his face while playing college baseball.

I would say around 2014 is when we started noticing changes in Troy’s behavior. He was very forgetful, erratic, angry, and engaged in risky and impulsive behavior. He started to struggle with life in general, including with money and getting in trouble with the law. He had relationship issues with family members, friends, and with women. In hindsight, I don’t think he was capable of settling down due to the CTE. I was so worried about him all the time. By 2020, the only thing predictable about Troy was his unpredictability.

In the early morning hours of December 26, 2021, Troy was believed to be the person who started a fire at his girlfriend’s home. The house was destroyed but fortunately no one was home at the time. Several hours later I received a call to go check on him. I did and he was distraught like I had never seen him before. He would not let me in the house. Shortly thereafter, he shot himself in the chest. As he was being loaded into the ambulance, he told me he was sorry. I could not see where he had been wounded but asked him if he was OK. He said, “I’m gone.” He told the paramedic to tell me he was sorry, that he loved me and this wasn’t my fault. He made the paramedic promise to tell me. Troy died three hours later. We did not get a chance to see or talk to him again.

The Massillon Tiger Community honored him after his death. Bracelets were made and sold with his football number on them and engraved “#28 Forever T.E.” Baseball hats were made with his number, as well as jerseys with a picture of Troy on the inside of the back of the neck. This way, Troy could “have their back.” Family members started a crowdfunding and all of the funds are being held for his son. The person at the mall who made the hats said, “We have made so many of these hats in memory of Troy Ellis. He must have been someone very special.”

I need to emphasize that I am not attempting to glorify Massillon Tiger football. I’m simply telling a true story about my son and his history of being a Tiger. Massillon football fans tend to over glorify their players. The kids are put on a pedestal and it’s just too much at times. The players in this program are more revered than those at most college programs. Many players have gone on to college and it has been a big letdown for them. I look at football through a totally different lens now.

After Troy’s death, his brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 1 (of 4) CTE. Had I known more about CTE, I would never have allowed him to play football. I have learned so much more about CTE and the devastating consequences it brings. I would never advise anyone to play football, or any sport suspected of causing CTE. His glory days turned into his gory days because of CTE. Simply put, the glory days were not worth it. I strongly urge parents to do their own research into CTE and make wise choices for their children, including supporting CLF’s Stop Hitting Kids in the Head. I certainly wish that I had. It’s too late for me now.

Troy said to me, later in life, “Football is a violent game, played by violent men.” After he passed, we were told that Troy had shared with others that he had “demons in his head and he was scared for himself.” He also said there was something wrong between his ears. He never shared that information with us.

We are all devastated and continue to carry a heavy load of grief, and the guilt that comes along when a loved one takes their own life. We love and miss him constantly.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Ryan Freel

John Hacker

We fell in love with John at first sight on March 25, 1980, and that will always be. We thought we had the perfect family and the perfect life.

We lost our beautiful, gifted son tragically 39 years later leaving us to somehow piece together an inexplicable puzzle. We never dreamed CTE would be our story, but we are grateful to the UNITE Brain Bank team for their knowledge and compassion as we travel this path. They have given us some answers to our questions we believed had no answers.

Our son John was a joy from the beginning. He wore a mischievous grin and twinkle in his eye that earned him lots of love and many friends.

From a very early age, he excelled in music and sports. He played violin and piano for us and he passionately played anything with a ball and friends for himself. That passion and intensity never changed with the many teams for which he played.

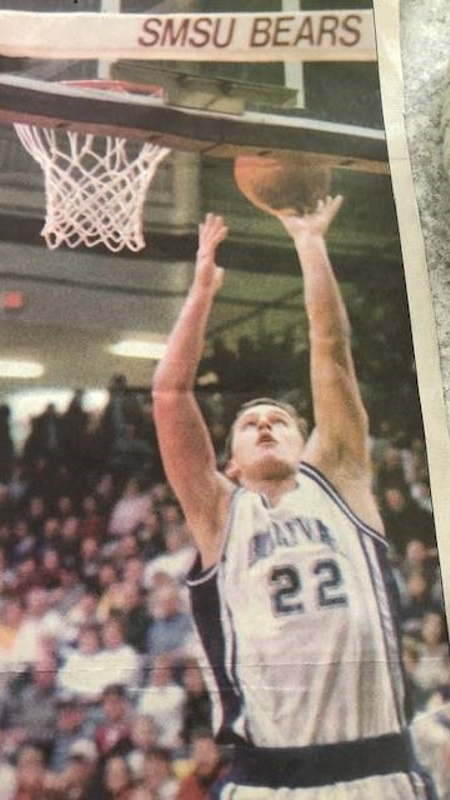

John played sports year-round, both at school and with travel teams. He always played at full speed whether it was practice or for a championship. We filled our summers with many trips, awards, and friendships. He also loved to run, and he was fast, holding the record in Missouri in the 50 and 100-yard Hershey Meet. The performance won him a chaperoned spot to compete nationally where he placed third two years in a row.

John loved varsity sports and was named captain of his baseball, basketball, and football teams his senior year in high school. He was recruited for college programs in each sport. He was plagued by injuries throughout his athletic career breaking both feet his senior year and, of course, numerous head injuries. Because of his history of injuries, he decided to play D1 baseball at Missouri State rather than the riskier offer of football at MU. We applauded that decision and felt a sense of relief as we hoped for a more injury free future.

John also did well academically. He had been placed in gifted education in elementary which he did not particularly enjoy. He was glad to rejoin his friends as soon as we allowed him to drop out of the program in middle school. He made high honor roll every quarter throughout his academic career and was named All-State Academic and Scholar Athletic Award in high school. He also loved to sing and was in honor choir and earned state vocal music honors. He was named Bolivar High School Outstanding Bass. His life looked so bright.

John dropped out of MSU baseball his sophomore year for a variety of reasons including another injury. He also had a tentative plan to attend law school and knew he needed to buckle down. He was accepted as a student at the Creighton University School of Law and graduated from there 3 years later. He enjoyed both his undergrad and law school experience, again making many friends that valued him for his kindness and sense of humor. He continued to maintain these friendships until his death. John never left a friend behind and they came by the hundreds to his memorial service; friends from his youth sports, high school athletics, college players and many of his fellow attorneys. He was beloved by everyone.

I’m not sure when we began to notice John changing. I do remember he came home from law school unexpectedly, citing depression. We did not take it as seriously as we should have. We cheered him up and sent him back. It was just so hard to believe that a guy that seemingly had everything was depressed. Our hindsight is clear. It was the beginning of traces that we would much later attribute to CTE.

John graduated from Creighton Law School and passed the bar exam on the first try and was hired by a well-known firm that he had interned with in college. Eventually, he started his own practice and married a lovely girl. Together they had two children that were the center of their lives. His family meant the world to him and they were loved and adored. Most days looked good from our perspective, but we now know John was very adept at hiding symptoms. He was not one to draw attention to himself and he did not want us to worry. We did begin to see signs of a struggle as his health declined. We sought a variety of medical help with no definitive answers.

John was well known and respected in the legal field and was honored to receive the Equal Access to Justice Award. It was evidence he believed all people deserve legal representation, and he took many cases with little or no fee. While representing such a case two years prior to his death, John suffered a seizure while in court and was hospitalized for several days. The seizure was the turning point in all of our lives. We began to seek answers in earnest. John suspected he could be experiencing symptoms of CTE. When he told us, we wanted it to be anything else, knowing the prognosis. CTE can only be diagnosed postmortem so at this point we didn’t have answers, but the possibility was frightening.

The following years were filled with both good and bad times. The bad days became more frequent as time took its toll. John somehow managed to continue with his law practice, coach Jack and Annie’s teams, and hang out with friends although we were all very worried. He was hospitalized several times, again never with any real answers or help.

The second week in November 2019 John disappeared after a visit to our lake home. He had not been well and came to our house for a few days of peace and quiet. He was depressed, somewhat confused, and had a severe headache. As the week passed, he felt better and planned on coaching Jack’s game on Saturday morning. When we woke up that morning, John was gone. He was reported missing and after an exhaustive 4-day search, he was found in shallow water, lakeside. We do not know exactly what happened that night. We did not see any cause for alarm. We will always think it was another seizure. Maybe not.

After John’s death, we sought the help of the Concussion Legacy Foundation because of John’s sports related concussions and his own opinion that something was terribly wrong in his head. We needed definitive answers and had nowhere to turn so we decided to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank where researchers diagnosed Stage I CTE. With the encouragement and support of CLF, we have spoken out on our local tv channel as well as our newspaper in an effort to arm other parents with the information of the danger of playing contact sports at an early age. We believe this is what John would have wanted. If only we had this information sooner, we would have made very different decisions.

We will forever miss and love our beautiful son who we believe suffered and died because of early participation and injuries suffered in contact sports. His life was a blessing. His death destroyed us.

John was diagnosed with CTE even though he stopped playing contact sports after high school. In hindsight, John suffered a lot of head trauma while he was in high school and before that could have been avoided. The very first play of junior high football in seventh grade he was knocked unconscious on the field.

Knowing what we do now, we wouldn’t have taken the risk. We want other parents to understand that letting children play contacts sports is exactly that, a risk.

The Flag Football Under 14 campaign is the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s awareness and education program designed to help parents make informed decisions about youth tackle football. The Concussion Legacy Foundation strongly recommends that parents wait until age 14 to enrolling children in tackle football. Learn why.

Zach Hoffpauir

On Saturday, May 30, 2020, hundreds gathered at Christ’s Church of the Valley in Peoria, Arizona, to celebrate the life of Zach Hoffpauir. Two weeks earlier, Hoffpauir passed away from an accidental overdose at age 26.

The speakers who eulogized Zach had all coached him, played football or baseball with him, or grown up with him. Several themes emerged from their tearful tributes.

One – Zach Hoffpauir was unwaveringly committed to his faith and to his family.

Two – Zach Hoffpauir danced well and danced often.

Three – Zach Hoffpauir accomplished a great deal, but what he did was not who he was.

He was the uniter in his family and in his locker rooms. He was the friend who picked up the phone. He was the player who both took coaching and pushed his coaches to get better. He was everything to everybody.

But as much of a light as he was for others, Zach Hoffpauir struggled to find his way out of his own darkness.

“Sometimes he had so much love for other people,” said Christian McCaffery, Zach’s Stanford football teammate at the celebration of life. “That he didn’t have enough love for himself.”

THE NATURAL

Whatever Zach Hoffpauir touched, he excelled in. His father remembers him first catching a ball when he was nine months old, dribbling a basketball by two, and catching his first fish on a fly rod when he was four.

“At his first soccer game, Zach played like a man among kids,” said Doug Hoffpauir. “He was a natural at just about any sport he played.”

Zach grew up in Peoria, Arizona, receiving a private, Christian education. After eighth grade, he decided he wanted to attend public school and went to Peoria’s Centennial High School.

Prior to high school, Zach played one year of eight-on-eight tackle football. He quickly made a name for himself on the Centennial freshman football team. As the calendar turned his freshman year, Hoffpauir went on to start at point guard on the school’s basketball team and nearly hit .400 on the baseball team.

Despite being an athletic supernova, Zach remained remarkably humble. At Zach’s celebration of life, Stanford administrator Ron Lynn described Zach as “a young man with an old soul.” Centennial High’s football coach Richard Taylor added a similar sentiment.

“I had a teacher come up and tell me once,” said Taylor. “That speaking to Zach was like speaking to an adult.”

In a practice his sophomore year, Taylor saw Zach take a hit so big his helmet rotated 90 degrees across his face. Football was still relatively new to Zach, so Taylor worried the hit would scare Zach away from the sport. Instead, Zach found his favorite part of football.

“This is fun,” Zach told Taylor once his helmet was on straight.

Zach gave up basketball to focus on football and baseball. He excelled in both and became one of the best athletes in Centennial history. Zach decided to attend Stanford University, where he would continue football and baseball.

CARDINAL

Athletically, Zach’s freshman year in Palo Alto was not as prolific as his freshman year at Centennial. He played primarily on special teams in football and struggled mightily in baseball. The statistical production wasn’t there yet, but Zach Hoffpauir didn’t need to produce on the field to make an impact on his teams.

“He was just a light,” said Tyler Thorne, Zach’s Stanford baseball teammate, at his memorial service. “He had a unique ability to understand people from all walks of life.”

Hoffpauir’s freshman slump was a blip in an otherwise decorated career in Palo Alto. His junior year, Hoffpauir earned All-Pac-12 honorable mention as a safety in football and as a right fielder in baseball.

His athletic talent and intense loyalty were both on display in a chippy series against rival Cal in April 2015. Zach went 6-12 with three home runs in the series, including an infamous post-homer stare down with a Cal pitcher who had been taunting Stanford.

“Don’t mess with his friends, don’t mess with his family,” said Lynn. “Because if he had to, he would challenge you and he would step up and say, ‘This is not right.’”

At Zach’s memorial service, Stanford football coach David Shaw reflected on Zach’s willingness to speak up to the Stanford coaching staff when he thought change was necessary.

“He challenged me,” said Shaw. “He made me better.”

After the Arizona Diamondbacks selected him in the 22nd round of the 2015 MLB Draft, Hoffpauir took a year off from football to spend a season playing minor league baseball. He then returned to Palo Alto for a fifth-year senior season in 2016.

“LOUD AND PASSIONATE”

At his memorial, Zach’s pastor said, “Everything Zach did was loud and it was passionate.”

His playing style for Stanford football was no exception.

In a September 2019 interview on “Untold,” a podcast hosted by fellow former Pac-12 safety Jordan Simone, Zach estimated he had five or six “on the record” concussions, and that at least two of them came in the 2016 season.

In four seasons at Stanford, Zach amassed 102 total tackles. He made 137 more in high school and was in on hundreds of others playing running back and wide receiver. As he did with all things, Zach put his all into every hit.

“Zach was the hardest hitter, most aggressive player I ever played against,” said McCaffery at the memorial.

The totality of the damage brought Zach’s football career to an end. He had to medically retire due to concussions prior to Stanford’s bowl game in 2016.

“It was a stripping of identity for me,” said Zach about the retirement on the 2019 podcast.

“THERE IS SOMETHING WRONG WITH MY HEAD”

For most his life, Zach Hoffpauir was guided forward by sports. The next play, the next at-bat, the next game, the next sport, the next season. Once college was over, Zach struggled with the lack of a “next.”

“After Stanford and the finality of not being able to play beyond college, he struggled with what to do in life,” said Doug Hoffpauir.

The loss of identity was hard enough, but Zach also endured his parents’ divorce, his grandmother’s lung cancer diagnosis, and a breakup in short succession after he left Stanford.

Zach moved in with Doug during this time. Normally, Doug says Zach would be able to rebound quickly from things. But this time, Zach entered a deep funk.

He had trouble sleeping as his mind raced at night. His mood changed. He had a shorter fuse and he snapped at friends and family more quickly. The mini explosions were always followed by apologies. Doug could tell he was cognizant of and upset by his mood changes.

Doug remembers his son saying to him that, “there is something wrong with my head. I don’t want to act and feel this way. I just want to feel normal.”

“I walked through his darkest days right by his side,” said Doug. “I felt helpless because I wanted to fix things for Zach, but I did not know what was really wrong.”

Zach’s physical and mental health were failing him. On top of the depression and anxiety, he was diagnosed with Lyme Disease in 2019, which weakened his immune system. He also contracted Valley Fever and meningitis.

On “Untold,” Zach shared how deep his emotional pain went. He detailed how in spring 2019 he attempted to take his life by overdosing on Xanax and Benadryl.

Surviving the attempt led Zach to realize he needed help. He couldn’t fight this alone.

HEALING

After the attempt on his life, Zach slowly found his footing with a combination of medication, therapy, and self-reflection.

The neurologist who diagnosed Zach with Lyme Disease prescribed him medication to help him stay balanced.

Zach also began seeing mental health professionals. On “Untold”, Zach shared how a psychologist helped him learn how his sense of self-worth had plummeted after Stanford because he felt he was no longer living up to external expectations.

“We, as his family, believed that he could do whatever he wanted in life,” said Doug. “We were celebrating his accomplishments not knowing that it caused a lot of pressure for him to perform.”

He also shared how he increased his emotional literacy and was able to name the emotions he was feeling rather than bury them.

“People always thought I was the happiest guy,” Hoffpauir said on “Untold”. “Inside I was so miserable. But I would fake it.”

Gratitude became an important part of Zach’s healing process. He began writing whenever he felt anxious, listing whatever he felt grateful for in that moment to ground him.

Zach also started coaching back at Centennial High. His same ability to connect with people that made him such an outstanding teammate made him an instant fit in coaching. So, when Ed McCaffery, the former NFL player and Christian’s father, took the head coaching position for the University of Northern Colorado in February 2020, Christian recommended his father add Zach to the coaching staff. Zach took the job as a defensive backs coach at NCU.

“He was a young, intelligent coach with limitless potential,” wrote Ed McCaffery in a Facebook post after Zach’s death.

MAY 15, 2020

The night of May 14, 2020, Zach Hoffpauir and Shaw spoke on the phone for several hours. With Zach preparing for his first season at NCU, he spoke with Shaw about the craft. He told Shaw how he had identified the most important quality in any great coach was not discipline, communication, or any tactical trait. It was compassion, Zach said.

Zach Hoffpauir did not wake up the next morning. He died of fentanyl toxicity. According to his mother, he took a Percocet to help him fall asleep and did not know the pill was laced with fentanyl.

His death sent shockwaves into the Peoria, Stanford, and broader football community. Following Zach’s death, Doug was contacted about donating Zach’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank for CTE research.

“My family wanted answers to help us process the loss of Zach,” said Doug. “We also knew that this research could help others, and that is exactly what Zach would want.”

Months later, Brain Bank researchers informed the Hoffpauirs that Zach had Stage 2 (of 4) CTE. He had multiple lesions on the frontal and temporal lobes of his brain.

“Just imagine what Zach’s parents are going through,” said Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the UNITE Brain Bank, in a 2021 documentary from Sports360AZ about Zach’s life. “This beautiful, talented, incredibly intelligent young man dying at 26 with the ravages of this disease in his brain.”

The diagnosis helps explain why Zach’s mood and behavior changed so much once he left college.

“The results provided closure,” said Doug. “Now we better understand why Zach struggled so much during the last few years of his life.”

“HE’D BE IN YOUR HEART”

On stage at Christ’s Church of the Valley after Zach’s death, Tyler Thorne urged those in attendance to live as Zach did – to be completely present for the needs of others.

“It’s hard to find people who when you’re around them and they’re truly present,” said Thorne. “He’d be in your heart.”

Zach’s cousin, J.D. Cavness, expressed the same feeling in his eulogy.

“He stood for caring for others,” said Cavness. “No matter where they came from, no matter their circumstances.”

Zach Hoffpauir’s legacy undoubtedly lives on in the example he set for how to treat others.

Zach also set an important precedent by talking about his own struggles with mental health and encouraging others to seek help in their darkest hours. In the closing moments of his “Untold” interview, Zach spoke about the power of vulnerability and opening up to others about what you’re going through.

“We are more similar than we are different,” said Zach. “And we connect in weaknesses.”

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms or possible CTE? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.