Jack Heidbrink

Terry Henigan

Glen Ray Hines

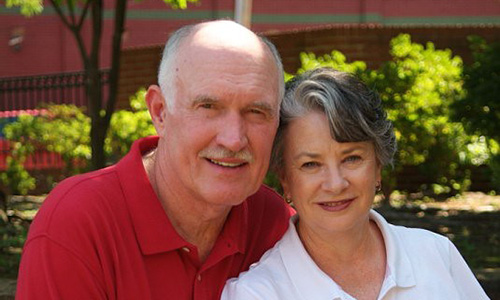

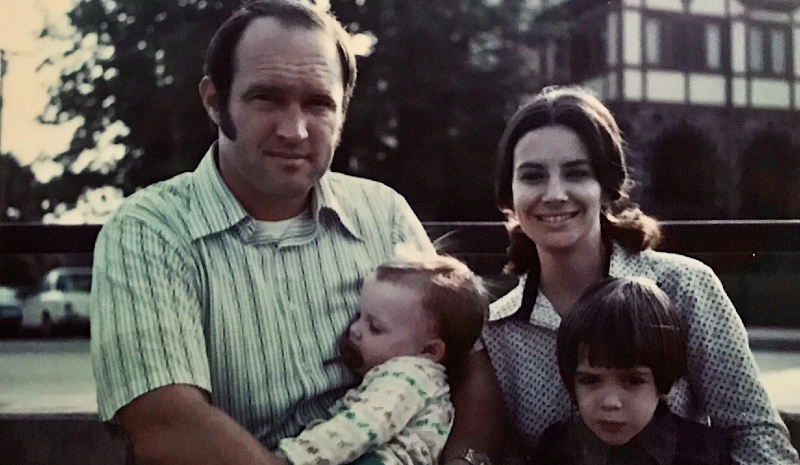

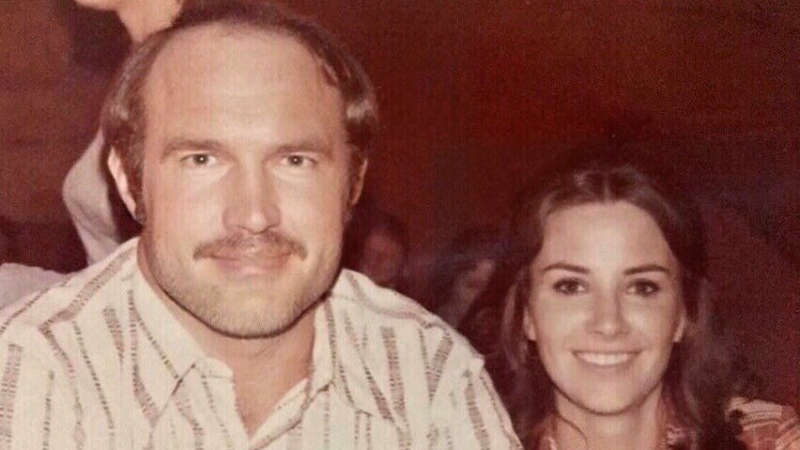

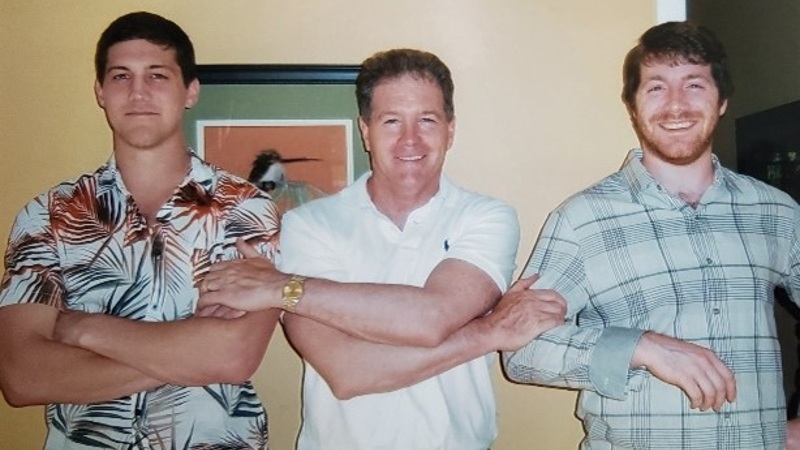

My father Glen Ray Hines was born October 26, 1943, in El Dorado, Arkansas. He graduated from El Dorado High School in 1961, and attended the University of Arkansas from 1961-1965. He and his family lived primarily in the Houston, Texas area, where myself, my brother Wes and sister Sheila were born, before he and our mother moved to the northwest Arkansas area.

Above all things in his life, Dad loved his wife, children, and grandchildren. He met our mother Jody, his high school sweetheart, in their teens and they married in 1965. Dad was first and foremost a family man. He took an avid interest in his children’s education and extracurricular activities, but the event he was most proud of in our lives was our individual acceptance of Jesus Christ as our personal Lord and Savior.

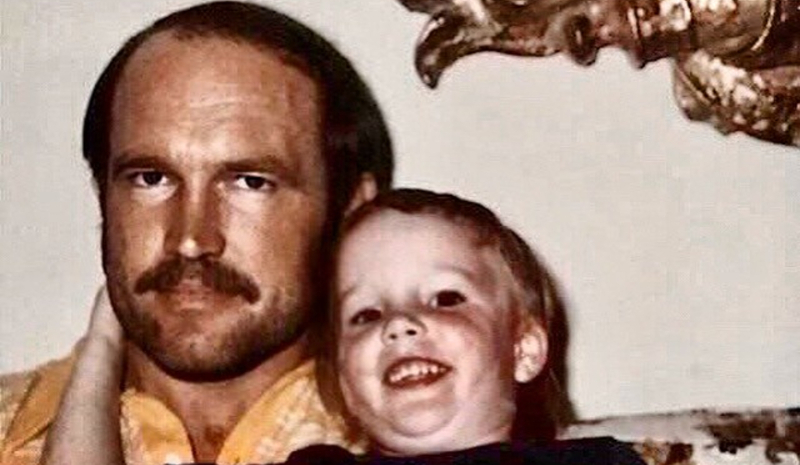

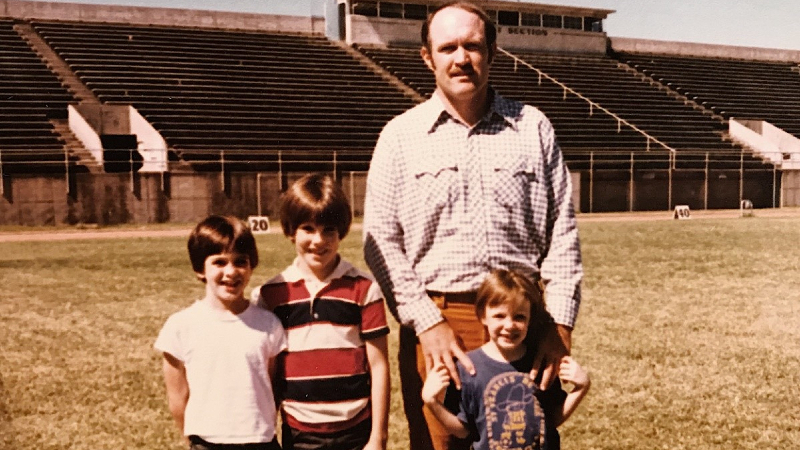

I’ve often told people that Dad was a big man, but he cast a very small shadow. He was a quiet man who preferred action over words. The most humble man his children ever knew, he would much rather speak with you about the latest accomplishments of his children or grandchildren than anything he had accomplished himself. I’ve never known another man to spend more time, quality and quantity, with his children. During our formative years, he was completely and totally invested in everything in our lives, and if you asked him, he – in a rare moment of being prideful – would tell you this investment paid off. After his children were grown with families of their own, he took a keen interest in his grandchildren’s lives, always asking about their education and activities, and in his later years, he enjoyed nothing more than attending their athletic and scholastic events.

Indeed, our father was his children’s hero, but not because of anything he did on an athletic field. That was a small, finite period of his life. He played football for only 15 years. He lived for another 60. It was what he did during the other 60 that mattered, at least to his family. It was what he did in those other 60 years that bore fruit. It was an investment that paid off.

As much as I might want to overlook it, we must admit football was, without question, a significant part of his life. It affected his life as well as ours, in many different and conflicting ways. As much as football impacted his life, he in turn, left his own, influential mark on the history of Arkansas Razorback and Houston Oiler football.

A two-sport standout at El Dorado High School in Arkansas, he played collegiately for the University of Arkansas Razorbacks from 1961 to 1965. In 1964, he was the anchor of an offensive line that helped Arkansas win its only National Championship in football, and in 1965, he was a consensus All-American. The Houston Post named him the Southwest Conference’s Most Outstanding Player for the 1965 season, a rare honor for a lineman. In 1989, Dad was named as one of the best two offensive tackles of all-time in the 82-year history of the Southwest Conference when he was named a member of the Express News San Antonio, All-Time Southwest Conference Football First-Team Offense. In 1994, he was selected as a member of the Arkansas Razorback All-Century team. He was inducted into the Razorback Sports Hall of Honor in 2001 and the Union County (Arkansas) Sports Hall of Fame in 2012. In October 2018, he was inducted into the Southwest Conference (SWC) Sports Hall of Fame.

In 1965, there were two professional football leagues, the NFL and the AFL, and Dad was drafted by both; the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals, and the AFL’s Houston Oilers. In 1966, he signed with the Oilers and played for Houston until 1970. He played the 1971-72 seasons with the New Orleans Saints, and retired after his final season with the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1973.

Dad was an accomplished pass blocker at a time when offensive linemen were severely restricted in the use of their hands to block pass rushers. He was an AFL All-Star game selection, the AFL version of the Pro Bowl, in 1968 and 1969. A model of durability, from his first season in 1966 through his final season in 1973, he started and played in 115 consecutive NFL games, including three playoff games. In December 2005, the Football Digest named him to the All-Time Houston Oilers Team.

But all this achievement and recognition that American society places so much value on, at least while football players are in the public eye, eventually came at a big price to my father and our family.

Shortly after he retired from the NFL in 1975 at the age of 32, Dad began to show some early symptoms that have become all too familiar to other football players and their families. When he was diagnosed many years later with serious neurological disease and probable Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), these symptoms started to make sense in hindsight, but at the time our family had no idea what to make of them. He was reclusive. He was always writing things down in notebooks, which he had countless numbers of around the house that he would keep long after they were completely filled. We didn’t know why. He experienced sudden fits of anger that seemed to be way out of proportion to the precipitating cause. He would close himself off from people. He went through dark moods that made him unapproachable. He had difficulty maintaining a job, although he was offered numerous opportunities. His explanation at the time was that the jobs took too much time away from being able to spend time with his family. But we suspected there were other issues at play that made it very difficult for him to maintain steady employment. He avoided attending any functions that required him to speak publicly and did not often attend reunions of his football teams. People concluded he was aloof, standoffish, and even arrogant. But they had no idea what was really going on.

He also suffered from an acute, palpable depression that no one could understand, least of all him. It debilitated him, and in turn, it debilitated our family. Our fellow “football families” who have been through these same experiences can understand this and how this insidious affliction affects not only our loved one – our father, our brother, our son – who played the game, but it also leaves a wide path of damage in its wake that impacts everyone who loves and cares about them.

When it started to manifest itself, Dad even wrote letters to his children attempting to explain what he was going through.

“I can’t explain what exactly happened to me,” he wrote. “Lately I’ve been having more and more doubts of whether I will ever get back on track. It seems like nothing ever works out for me, though I still consider myself the luckiest man in the world and I have much guilt about letting myself get down after I have been blessed with so much in life. However, I haven’t given up, and I will continue to try and make something positive happen with my life. As long as I can breathe, I have a chance.”

He was still a relatively young man when he wrote this, but he knew there was something wrong. The real miracle of our father during these years was the fact that he was so strong, he was somehow able to hide much of this and keep it under control for the most part; to live with it while at the same time knowing he had some kind of strange affliction that he couldn’t understand. This is why during his last days, most of his friends expressed shock that he had taken such a rapid physical and mental crash that he was in hospice care within the span of about two weeks. No one had any idea how bad his condition was, nor how long it had existed.

Later in life, his physical and cognitive decline became more rapid and advanced, and he was eventually diagnosed with advanced dementia that his doctors found resulted from his football career. He decided to donate his brain for analysis to the Boston University CTE Center. Almost one year after his death, in January, 2020, the Boston University CTE Center diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE, the most advanced and severe form of CTE. There was “global spread” of the disease to every part of his brain and even in deeper parts of the brain rarely observed in other cases.

But football and his CTE diagnosis are not his legacy.

Despite what football did to him, he was still able to overcome it, until nearly the very end. With perseverance, he ran the race marked out for him, and he won.

His legacy is that he was an example. He was an outstanding role model for his children. He was the example of what a Christian husband should be. He was the example of a good Christian father and grandfather. He was the example of a humble Christian servant. And he was an example of a good and loyal friend.

This is the legacy he gifted us. And these are the things we will remember.

We are very thankful to the incredible staff at the Boston University CTE Center and the Concussion Legacy Foundation, especially Lisa McHale and Dr. Thor Stein, for their dedication and hard work, and the professionalism they exhibited from the first hours after Dad passed away through the long wait to find out the results of his testing.

Ryan Hoffman

Ryan’s life slipped away in the ER at Heart of Florida Hospital, Haines City, FL, on November 16, 2015. He died from massive head injuries resulting from a crash with a car in Haines City. He was visiting with his mother at the time of the accident. He was riding down the wrong way on the road into traffic on his bicycle and struck by an automobile, according to the only witness, the driver of the car that killed him. It was a tragic end to a long story of the havoc that Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) causes its victims and those closest to them. Ryan had struggled for nearly twenty years with the effects of this disease, CTE, a fact which could not be substantiated at the time to either himself, physicians, friends and family. CTE cannot be definitively assessed until a post mortem procedural autopsy is performed on the brain. Ryan’s brain was donated by his family posthumously because they felt it was what Ryan would have wanted: them to know the answers. Also, they felt he would want it for others who might have CTE. Hopefully, research will provide a cure and remedy for those who suffer from CTE, but currently that is not the reality. It wasn’t for Ryan. He could not get an accurate diagnosis for the symptoms that he suffered for years, going into stage II-III CTE, or a treatment program that was effective. To date there is no treatment available. The full extent of its effects are still not conclusively known, in entirety, but it seems that its victims have a common thread of a downward spiral of debilitating symptoms, depression and often suicidal consequences.

As a child, Ryan was always larger, stronger and more physically active. He was an outside kind of kid, either riding his bicycles, flying by on his skateboards, surf boarding when he was older. He like to ski and to swim, and he always had friends. For Ryan, outside of sports, friends were among the most important things in his life. He always had a lot of them. Ryan was very social and outgoing. Ryan was a happy child and a well-adjusted adolescent. He had no issues with negative behaviors, kept up a high grade point average in school, was highly regarded by his teachers and coaches, and was very organized in his personal habits. He kept to a schedule, and followed the rules in the home.

Ryan was heavily recruited by Division I schools his senior year in high school. When he decided on UNC and went off to college it was his dream come true, to be a Division I player and to get a scholarship to a great college. He accomplished that dream and the family was all proud and excited for him. It was a great time of his life, as he seemed to be on top of the world. He stayed on as a starter on the football team at UNC five years. He loved the school and he was well liked and highly regarded by his coaches and teammates. His senior year he was nominated MVP. He played left tackle and was a strong contributor to the successes of the team while at UNC. Ryan played in several bowl games and showed that he was a player with great heart. There are no school records showing that Ryan was diagnosed with a concussion during college or high school for that matter, no incidents of his exhibiting outwardly the symptoms of concussion. But it is now known that it isn’t necessarily the concussions that produce symptoms that contribute to CTE, but the continual head banging and shock to the brain that is the cause of CTE, one of the reasons why it’s not possible to assess the consequences so easily. It’s the repetitive jarring of the brain as it hits the skull during contact sports, and Ryan’s position was a head banger position, being a left tackle and in the snap, colliding with equally big and strong defensive linemen head to head. The family attending the games and the coaches and players had no real way perhaps to measure the damages being done, so little was widely known of this silent disease or its consequences until recently. The other factor is that not all players get CTE as a result of playing contact sports. The answer to this tragedy lies in the research now being done to both prevent and hopefully find relief and a cure for the disease. And then for the football programs to extend help to its victims, like Ryan, who often become debilitated to the point of not being able to provide for themselves necessary medical care or in some cases to even be self-sufficient ultimately.

The changes in Ryan post UNC were dramatic and notably uncharacteristic when compared to the Ryan his family knew for the first twenty-two years of his life. Ryan started showing symptoms that something was going seriously wrong within a few weeks of leaving UNC. He was then living with his father, and his sister, Kira, became aware that he was having shocks to his head that woke him out of sleep, and he complained of dizziness and headaches. He lost weight and started having sleeping problems and symptoms not unlike PTS. He started having problems with staying organized, and his sister noticed that he kept everything in his room in plastic bags, lined up in neat piles rather than in the dressers in his room. He explained he had to see everything to remember where things were, and it eliminated frustration, searching through the drawers for them. He also often seemed to lose consciousness for brief periods, like small seizures. He would fall down and jump back up sometimes and explain that he had lost consciousness. He was sent to various doctors who could find nothing wrong with him. He would forget to close doors, leaving the house wide open, and in general seemed to forget details easily, lose his keys, wallet, phones, etc. His personality changed also. He was not the happy go lucky, upbeat person everyone knew Ryan to be throughout childhood, adolescents and his college years. He was clearly struggling and frustrated.

Ryan married and had a daughter after he came home. The marriage lasted until his daughter was around three or four years of age. He and his ex-wife remained friends over the years, and Ryan maintained a close contact with his daughter and his adopted son right up the end of his life. He truly loved his kids, and did what he could do to be a good father, but over the years his overwhelming problems took an enormous toll economically, physically and psychologically. He could not maintain adequate employment, and he survived living in various homes with friends and relatives, and uncharacteristic to those who he was prior to this, he had many brushes with law enforcement, mostly minor things, but enough to ruin his chances for gainful employment. He survived by working at construction jobs, roofing, day labor and other small jobs. The common consensus, however, of bosses and co-workers was that Ryan was one of the hardest workers they’d ever met. He lost many opportunities because of his disability. He was an accomplished welder and admitted to a prestigious welding school in a marine welding program in Jacksonville FL, but ultimately the life issues that plagued him from his injuries prohibited him from participating at the last minute, another of many in a long series of crushing disappointment in his attempts to better himself. He couldn’t seem to settle in life or find traction anywhere. His life was chaotic and left no quarter for raising children. He was adrift and towards the later years showing signs of depression, self-medicating, and increasing symptoms physically characteristic of CTE. He often had seizures that rendered him unconscious. He was depressed and manic, had trouble sleeping, and the misplacement and losing of objects grew worse. His family members tried to get him on disability but his case was repeatedly denied. He had issues keeping his driver license and had no ID on him at the time of his death. He could not maintain medical care for himself, jobless as he was and without any insurance. Had Ryan lived, going into stage III and then IV CTE, it is a surety that he would have gone into a full-blown dementia. His was a gradual downward spiral that caused dramatic changes in behavior, especially in the area of cognitive things, such as good judgement, memory, impulse control and anger management that is consistent with the autopsy at the BU CTE Center as to the severity and local of Ryan’s abnormal concentrations of proteins in the brain.

This is the terrible picture of what CTE can do to someone like Ryan Hoffman, an accomplished, big hearted boy who finds himself dwindling inexplicably after returning from the glory of his college years into a void of failures and disappointments. Often, he was misunderstood, perhaps the most difficult aspect, by people who judged the person and not the disease. Is there hope for people like Ryan? Let’s pray that there is and that this disease can be, as so many others have been, eradicated, understood and prevented for future generations. Let’s hope it will also be a wake-up call for parents, coaches, educators and the public who revere the sports but do not recognize the great risk and cost that often comes of them. Let’s hope that it in the future it won’t take a post mortem diagnosis to diagnose CTE so its victims may get the help they need from state agencies and the programs they come out of who they benefited by their sacrifices.

Ryan felt that there was something not right with his brain. He confided early on that he wanted his sister to make sure that his brain was donated in the event anything happened to him. Ryan offered to give the last thing he had, showing he was a generous soul who had an open hand to those who had needs around him when he had something to give. He will always be remembered and loved by those who knew him and he is greatly missed. Ryan’s star is rising on the horizon somewhere else now, and those who knew him are left with only the memories of his short life. Sadly, perhaps he did not realize this. Hopefully, he knows so now.

Zach Hoffpauir

On Saturday, May 30, 2020, hundreds gathered at Christ’s Church of the Valley in Peoria, Arizona, to celebrate the life of Zach Hoffpauir. Two weeks earlier, Hoffpauir passed away from an accidental overdose at age 26.

The speakers who eulogized Zach had all coached him, played football or baseball with him, or grown up with him. Several themes emerged from their tearful tributes.

One – Zach Hoffpauir was unwaveringly committed to his faith and to his family.

Two – Zach Hoffpauir danced well and danced often.

Three – Zach Hoffpauir accomplished a great deal, but what he did was not who he was.

He was the uniter in his family and in his locker rooms. He was the friend who picked up the phone. He was the player who both took coaching and pushed his coaches to get better. He was everything to everybody.

But as much of a light as he was for others, Zach Hoffpauir struggled to find his way out of his own darkness.

“Sometimes he had so much love for other people,” said Christian McCaffery, Zach’s Stanford football teammate at the celebration of life. “That he didn’t have enough love for himself.”

THE NATURAL

Whatever Zach Hoffpauir touched, he excelled in. His father remembers him first catching a ball when he was nine months old, dribbling a basketball by two, and catching his first fish on a fly rod when he was four.

“At his first soccer game, Zach played like a man among kids,” said Doug Hoffpauir. “He was a natural at just about any sport he played.”

Zach grew up in Peoria, Arizona, receiving a private, Christian education. After eighth grade, he decided he wanted to attend public school and went to Peoria’s Centennial High School.

Prior to high school, Zach played one year of eight-on-eight tackle football. He quickly made a name for himself on the Centennial freshman football team. As the calendar turned his freshman year, Hoffpauir went on to start at point guard on the school’s basketball team and nearly hit .400 on the baseball team.

Despite being an athletic supernova, Zach remained remarkably humble. At Zach’s celebration of life, Stanford administrator Ron Lynn described Zach as “a young man with an old soul.” Centennial High’s football coach Richard Taylor added a similar sentiment.

“I had a teacher come up and tell me once,” said Taylor. “That speaking to Zach was like speaking to an adult.”

In a practice his sophomore year, Taylor saw Zach take a hit so big his helmet rotated 90 degrees across his face. Football was still relatively new to Zach, so Taylor worried the hit would scare Zach away from the sport. Instead, Zach found his favorite part of football.

“This is fun,” Zach told Taylor once his helmet was on straight.

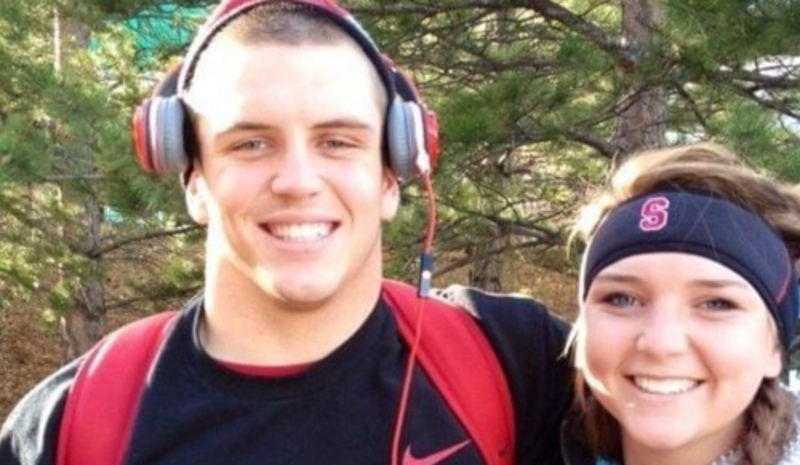

Zach gave up basketball to focus on football and baseball. He excelled in both and became one of the best athletes in Centennial history. Zach decided to attend Stanford University, where he would continue football and baseball.

CARDINAL

Athletically, Zach’s freshman year in Palo Alto was not as prolific as his freshman year at Centennial. He played primarily on special teams in football and struggled mightily in baseball. The statistical production wasn’t there yet, but Zach Hoffpauir didn’t need to produce on the field to make an impact on his teams.

“He was just a light,” said Tyler Thorne, Zach’s Stanford baseball teammate, at his memorial service. “He had a unique ability to understand people from all walks of life.”

Hoffpauir’s freshman slump was a blip in an otherwise decorated career in Palo Alto. His junior year, Hoffpauir earned All-Pac-12 honorable mention as a safety in football and as a right fielder in baseball.

His athletic talent and intense loyalty were both on display in a chippy series against rival Cal in April 2015. Zach went 6-12 with three home runs in the series, including an infamous post-homer stare down with a Cal pitcher who had been taunting Stanford.

“Don’t mess with his friends, don’t mess with his family,” said Lynn. “Because if he had to, he would challenge you and he would step up and say, ‘This is not right.’”

At Zach’s memorial service, Stanford football coach David Shaw reflected on Zach’s willingness to speak up to the Stanford coaching staff when he thought change was necessary.

“He challenged me,” said Shaw. “He made me better.”

After the Arizona Diamondbacks selected him in the 22nd round of the 2015 MLB Draft, Hoffpauir took a year off from football to spend a season playing minor league baseball. He then returned to Palo Alto for a fifth-year senior season in 2016.

“LOUD AND PASSIONATE”

At his memorial, Zach’s pastor said, “Everything Zach did was loud and it was passionate.”

His playing style for Stanford football was no exception.

In a September 2019 interview on “Untold,” a podcast hosted by fellow former Pac-12 safety Jordan Simone, Zach estimated he had five or six “on the record” concussions, and that at least two of them came in the 2016 season.

In four seasons at Stanford, Zach amassed 102 total tackles. He made 137 more in high school and was in on hundreds of others playing running back and wide receiver. As he did with all things, Zach put his all into every hit.

“Zach was the hardest hitter, most aggressive player I ever played against,” said McCaffery at the memorial.

The totality of the damage brought Zach’s football career to an end. He had to medically retire due to concussions prior to Stanford’s bowl game in 2016.

“It was a stripping of identity for me,” said Zach about the retirement on the 2019 podcast.

“THERE IS SOMETHING WRONG WITH MY HEAD”

For most his life, Zach Hoffpauir was guided forward by sports. The next play, the next at-bat, the next game, the next sport, the next season. Once college was over, Zach struggled with the lack of a “next.”

“After Stanford and the finality of not being able to play beyond college, he struggled with what to do in life,” said Doug Hoffpauir.

The loss of identity was hard enough, but Zach also endured his parents’ divorce, his grandmother’s lung cancer diagnosis, and a breakup in short succession after he left Stanford.

Zach moved in with Doug during this time. Normally, Doug says Zach would be able to rebound quickly from things. But this time, Zach entered a deep funk.

He had trouble sleeping as his mind raced at night. His mood changed. He had a shorter fuse and he snapped at friends and family more quickly. The mini explosions were always followed by apologies. Doug could tell he was cognizant of and upset by his mood changes.

Doug remembers his son saying to him that, “there is something wrong with my head. I don’t want to act and feel this way. I just want to feel normal.”

“I walked through his darkest days right by his side,” said Doug. “I felt helpless because I wanted to fix things for Zach, but I did not know what was really wrong.”

Zach’s physical and mental health were failing him. On top of the depression and anxiety, he was diagnosed with Lyme Disease in 2019, which weakened his immune system. He also contracted Valley Fever and meningitis.

On “Untold,” Zach shared how deep his emotional pain went. He detailed how in spring 2019 he attempted to take his life by overdosing on Xanax and Benadryl.

Surviving the attempt led Zach to realize he needed help. He couldn’t fight this alone.

HEALING

After the attempt on his life, Zach slowly found his footing with a combination of medication, therapy, and self-reflection.

The neurologist who diagnosed Zach with Lyme Disease prescribed him medication to help him stay balanced.

Zach also began seeing mental health professionals. On “Untold”, Zach shared how a psychologist helped him learn how his sense of self-worth had plummeted after Stanford because he felt he was no longer living up to external expectations.

“We, as his family, believed that he could do whatever he wanted in life,” said Doug. “We were celebrating his accomplishments not knowing that it caused a lot of pressure for him to perform.”

He also shared how he increased his emotional literacy and was able to name the emotions he was feeling rather than bury them.

“People always thought I was the happiest guy,” Hoffpauir said on “Untold”. “Inside I was so miserable. But I would fake it.”

Gratitude became an important part of Zach’s healing process. He began writing whenever he felt anxious, listing whatever he felt grateful for in that moment to ground him.

Zach also started coaching back at Centennial High. His same ability to connect with people that made him such an outstanding teammate made him an instant fit in coaching. So, when Ed McCaffery, the former NFL player and Christian’s father, took the head coaching position for the University of Northern Colorado in February 2020, Christian recommended his father add Zach to the coaching staff. Zach took the job as a defensive backs coach at NCU.

“He was a young, intelligent coach with limitless potential,” wrote Ed McCaffery in a Facebook post after Zach’s death.

MAY 15, 2020

The night of May 14, 2020, Zach Hoffpauir and Shaw spoke on the phone for several hours. With Zach preparing for his first season at NCU, he spoke with Shaw about the craft. He told Shaw how he had identified the most important quality in any great coach was not discipline, communication, or any tactical trait. It was compassion, Zach said.

Zach Hoffpauir did not wake up the next morning. He died of fentanyl toxicity. According to his mother, he took a Percocet to help him fall asleep and did not know the pill was laced with fentanyl.

His death sent shockwaves into the Peoria, Stanford, and broader football community. Following Zach’s death, Doug was contacted about donating Zach’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank for CTE research.

“My family wanted answers to help us process the loss of Zach,” said Doug. “We also knew that this research could help others, and that is exactly what Zach would want.”

Months later, Brain Bank researchers informed the Hoffpauirs that Zach had Stage 2 (of 4) CTE. He had multiple lesions on the frontal and temporal lobes of his brain.

“Just imagine what Zach’s parents are going through,” said Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the UNITE Brain Bank, in a 2021 documentary from Sports360AZ about Zach’s life. “This beautiful, talented, incredibly intelligent young man dying at 26 with the ravages of this disease in his brain.”

The diagnosis helps explain why Zach’s mood and behavior changed so much once he left college.

“The results provided closure,” said Doug. “Now we better understand why Zach struggled so much during the last few years of his life.”

“HE’D BE IN YOUR HEART”

On stage at Christ’s Church of the Valley after Zach’s death, Tyler Thorne urged those in attendance to live as Zach did – to be completely present for the needs of others.

“It’s hard to find people who when you’re around them and they’re truly present,” said Thorne. “He’d be in your heart.”

Zach’s cousin, J.D. Cavness, expressed the same feeling in his eulogy.

“He stood for caring for others,” said Cavness. “No matter where they came from, no matter their circumstances.”

Zach Hoffpauir’s legacy undoubtedly lives on in the example he set for how to treat others.

Zach also set an important precedent by talking about his own struggles with mental health and encouraging others to seek help in their darkest hours. In the closing moments of his “Untold” interview, Zach spoke about the power of vulnerability and opening up to others about what you’re going through.

“We are more similar than we are different,” said Zach. “And we connect in weaknesses.”

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms or possible CTE? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Zach Holm

Warning: This story contains mention of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Special. This is the word most often used to describe Zachary Ryan Holm. The first time we heard it was when he started played flag football at age six. Growing up in Florida, Zach was very blessed to have been coached by former NFL and college football players. From an early age, Zach was encouraged to work hard and was told he would be able to go as far in football as he desired. Zach took this to heart. He was a big kid, so he began playing competitive youth tackle football at age seven, playing every position on the team. At age 10, his coach called him “hybrid” because he was big, strong, fast, and smart. He started playing quarterback and continued all through high school. Going to a small high school in Colorado, Zach ended up playing both sides of the ball and led his team in touchdowns as well as tackles. Zach was recruited to play safety at the University of Wyoming. At six-foot, he was considered “short” for a quarterback but UW coaches were impressed with the hard hits Zach delivered on defense, so they recruited him to play safety.

Those hard hits over many years Zach delivered on defense, and the hits he took as a QB set him up for CTE. Zach had five known concussions, the first of which came at age nine. He started having problems with depression at age 13 and had difficulty sleeping and with concentration at age 16. Zach started attention deficit disorder (ADD) medication at age 18. The medication initially helped with depression and concentration, but the therapeutic effect started to wane. Zach was excited to be recruited to play football at a D1 school, but his depression worsened. He told me, “Mom, the football wasn’t hard, it was the depression that was difficult.” Zach resigned from the UW team during his freshman season in December 2016 and never returned to football. Zach’s first paper at UW was about CTE. He highly suspected he had CTE from playing 12 years of tackle football.

After UW, Zach transferred to a private college in Florida and really struggled with depression. He returned to Colorado to be near family. Zach battled suicidal thoughts and was open about his suicidality. Zach felt guilty about being depressed because he felt like he had everything going for him. He started feeling “numb” and said, “my brain is broken.” Zach participated in any form of therapy offered. He tried multiple medications and even ketamine infusions which helped for about 24 hours. He was compliant with every therapy and was disappointed when none of them helped. We talked about CTE. Zach knew it was a diagnosis only made at autopsy.

Zach attended a private Christian school in Tampa from ages four to 13. This is where his Christian faith was solidified. He was a leader both in the classroom and in every sport he played. Zach was called very “special” by his teachers and classmates. His kindergarten teacher described him as “a mix of sweetness and testosterone.”

Zach loved tattoos and had scriptures tattooed on his arms. In 2016, he decided to get a chest piece tattoo depicting a demon fighting an angel over his heart. Zach said he always wanted to be reminded he was not alone in his fight against depression and the devil.

Zach’s depression was growing worse, and he was getting daily headaches and hearing high pitched noises, causing physical pain. An MRI of his brain was normal. Medications were not helping with his mood. He was evaluated by five psychiatric professionals, the last of whom informed Zach he had treatment resistant depression. He tried nonprescription drugs which helped a little. Despite all these mental health challenges, Zach was attending the University of Colorado and getting excellent grades. Then he got COVID-19 in November 2020 and had to take a medical withdrawal. Zach was set to begin classes again in June 2021 with the eventual goal to attend law school. He was extremely driven as can be seen in the following excerpt from his LinkedIn page:

“Most people who know me describe me as a chronic perfectionist, as I give everything that I do my full attention and effort. In conjunction with time management, perfectionism is very beneficial. From my perspective, there is no point in me doing something if I do not intend to do it to the fullest of my capability. I am driven to be the best at whatever it is that I decide to do.

What differentiates me from the rest of the pack is my passion and drive for success, which is reflective with my persistence and consistency in terms of my work ethic; once I set my mind to something, nothing will be able to stop me from achieving it.

This is reflective of one of my firm views, which is the significant dislike of complacency. There is nothing more detrimental to the individual than complacency.”

Zach met a special young lady in the middle of his physical and emotional turmoil, and they were blessed to bring a beautiful baby girl into this world in 2020. Zach was an excellent father. His baby was the light of his life and became his purpose for living.

Zach became ill with acute respiratory symptoms in March 2021, and he took over the counter cold medicine which negatively interacted with his depression medications. He died from serotonin syndrome on March 27, 2021. We were able to donate Zach’s brain to Boston University for their CTE research. An hour after we heard of his death, we were contacted by Donor Alliance because he had signed up to be an organ donor. They described Zach as “special” because he was young and muscular and would be able to help about 50 recipients with the donation of his corneas, skin, bone, and muscle.

At Zach’s memorial and for months afterwards, we were contacted by people who had been touched by Zach’s life. Stories of him feeding the homeless, stopping someone from jumping off a bridge, and being a “special” person because of his incredible faith and love for his family. Zach always looked out for people who struggled. We often had stray kids staying at our house when they had difficulties at home. Zach was described as “kind,” and received the fruit of the spirit award at Christian school for “gentleness.” All of these attributes were far more important to him and to us than his stats on the football field.

Ten months after Zach’s death, we had a meeting with Dr. McKee from Boston University. She verified Zach had stage 2 (of 4) CTE. Zach had multiple lesions in various areas of the brain responsible for mood and impulsivity. Dr. McKee described Zach’s severe brain damage as unexpected in a 23-year-old. Also, it was no surprise to Dr. McKee hearing none of Zach’s medications really helped with his depression and anxiety.

This news from BU was devastating but also comforting, because Zach knew his brain was “broken” and he worked hard to stay ahead of his depression and suicidality. After meeting with Dr. McKee, I had my first dream about Zach after 10 months. In it, Zach was whole and happy. He also had a bounce to his step, and I am sure he was telling me, “I was right about my brain.” Zach always liked to be right!

We are blessed to know our very special son is still helping others. Zach’s experience and study participation are helping researchers to make changes in football so it is safer, and his death is helping to develop more useful ways to diagnose and potentially treat CTE. We are crushed about losing our son. At the same time, we are proud of his insight into brain injuries and his prediction regarding his CTE. Zach’s knowledge fueled our desire to donate his brain to Boston University. As everything else Zach did on this earth, his participation in the BU study was “all in.”

Don Horton

Thomas Wilson Hotze

Charles Hourihan

My husband Charlie began playing football at 11 years old in the youth football league in Boston. He then went on to play running back and become co-captain of his high school football team at Catholic Memorial in West Roxbury, MA.

Charlie continued his education at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester on a full football scholarship. He played defensive back there and was on special teams. He received a terrible concussion at one of the away games and was hospitalized for three days. I would like to think these days he would be told not to play anymore. Back then they had him come back and play. Charlie was very aware of the high cost of college. He was not going to give up his scholarship.

Charlie and I married in 1990 just as he turned 33 and I was 24. I thought everything about him was so special. His smile always made my heart melt.

We soon had two sons and he was such a wonderful father and husband. I couldn’t have wished for more. I was so grateful.

Charlie had moments over the following years that began to give me pause. Forgetting things not long after we had discussed them. Seeming to struggle a bit with work. Charlie had always excelled at work. Things were beginning to feel “off.”

It was at the end of 2014 Charlie had his first major panic attack (that I was aware of and witnessed). He told me everything was becoming hard, too complicated. He questioned his ability to work at the level he was used to. Charlie took so much pride in caring for his family. He was feeling devastated. My usually calm, loving husband was beside himself with anxiety and grief.

We began seeing a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. A PET scan and several cognitive tests told us something was definitely wrong. He had mild cognitive impairment. The likelihood was that it would get worse with time.

Charlie was devastated by the news. We decided to try to manage it as well as possible and to focus on moving forward the best we could.

Charlie stayed and fought until February of 2021.

We spent the years in between seeing his neurologist regularly. Using antidepressants and Donepezil and other medicines and treatments that seemed to help a bit, each in their own way. Charlie took speech therapy and mindfulness classes. He did everything the professionals at Mass General suggested. He gave his best each day.

Charlie was always kind and loving. My sons and I were very fortunate that anger, paranoia, or violence were not part of our story. Amongst the medicine and treatments, we added many more wonderful memories; from traveling, to walks in the park, to simple meals together. We knew our time together was special. We knew the clock was ticking…

Charlie passed away on February 23, 2021. He was 63 years old. I miss him so much.

My son and daughter-in-law remembered we had all discussed donating Charlie’s brain to the Boston University CTE Center. They made the phone calls the day Charlie passed, and the organization responded with respect and immediacy. Charlie was found to have stage 4 CTE. He was also in stage 2 TDP-43 Encephalopathy (a dementia similar to Alzheimer’s Disease in presentation).

We are grateful to them and the Concussion Legacy Foundation for providing answers and support. We also appreciate that they continue their important work with purpose and determination to help others.