Doctors couldn’t find what was wrong with Michael Keck, but football star knew it would kill him

—

The Kansas City Star

Her head lay on her husband’s chest and she listened to his heart beat for the last time. He took his final breaths, his body pressing against her cheek. She held his hands, still warm, in a room full of doctors and nurses and the love of her life.

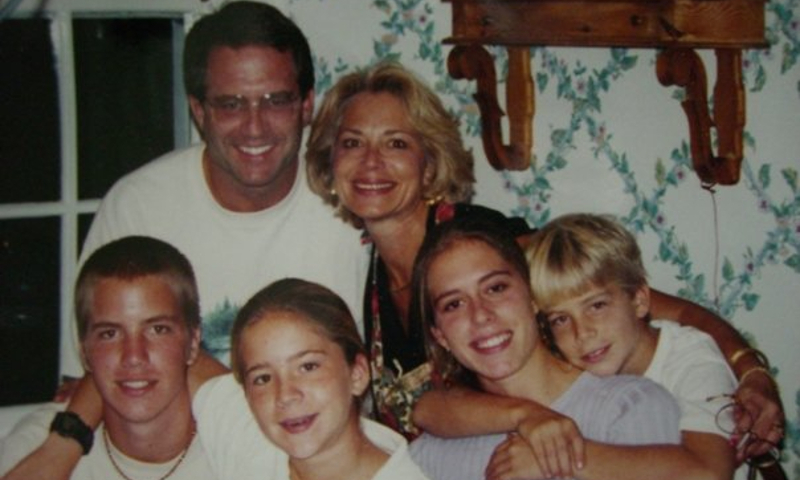

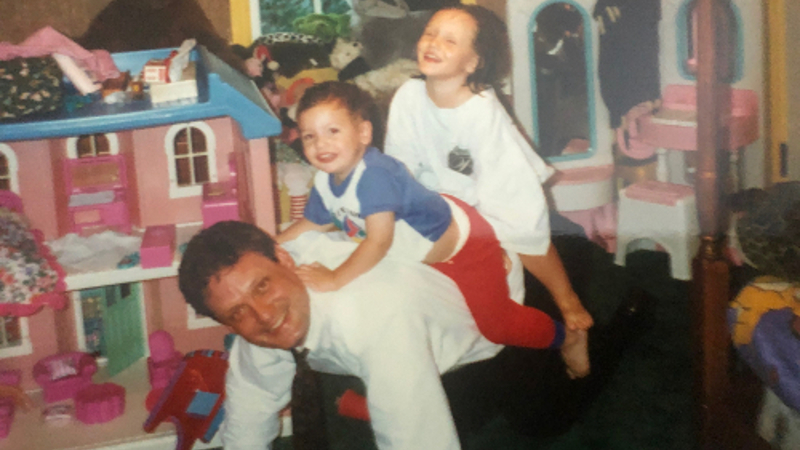

In the seconds after he slipped away, her first thought was of the way Michael Keck looked at their son. Such complete joy, like nothing else in the world mattered. She’d never seen anything like it. Still hasn’t.

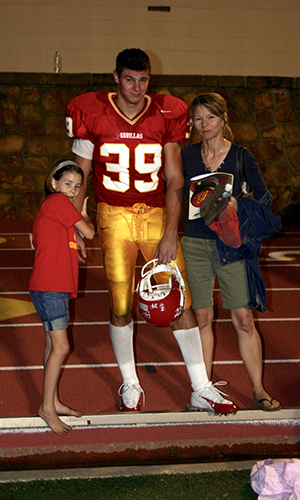

Michael was 25 years old. Should’ve had a full life in front of him. A former football star at Harrisonville High and later Missouri and Missouri State, with so much going for him.

He was smart, with an unrelenting energy. Kind and impossible not to like, except when the demons came. Justin, their son, was not yet 3 when Michael died in 2013, too young to remember anything about his dad. That’s one reason Cassandra wants to tell this story.

She walked her husband’s body to the morgue that day. They wanted to put him on a cold, plain, metal table. That seemed horrible to her. They kept him on the bed instead, and her father helped her clean Michael’s body. There was so much blood. His head was swollen, puffy, like a bag of water rested underneath his skin.

They had pushed on his chest for an hour, then two hours, then three, trying to bring him back to life. The trauma broke a blood vessel on his neck. Clamps held his eyes open. It was a gruesome end to what should’ve been such a long and beautiful life.

Michael and Cassandra were made for each other, sharing an inseparable bond even through the storm, and she was not ready for it to end. Football took Michael away at a startlingly young age, and that’s the other reason Cassandra wants to tell this story.

She tries not to cry.

“He was everything I wanted,” she said. “I was everything he wanted. Physically, mentally. It was like our souls were alike.”

At the crematorium, there was a tiny window. Cassandra watched his casket push into the flames. She saw it catch on fire. This was her way of saying goodbye to his body.

To the very end, she was by his side.

Michael Keck was a survivor. That’s what makes his death so hard to take even now, two years later, for those who loved him and knew him and looked up to him.

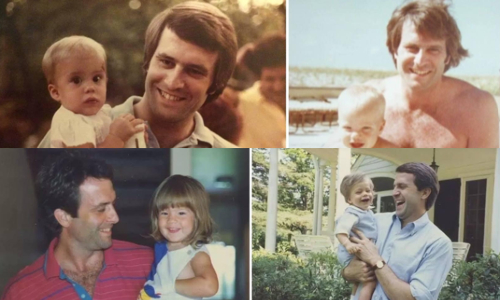

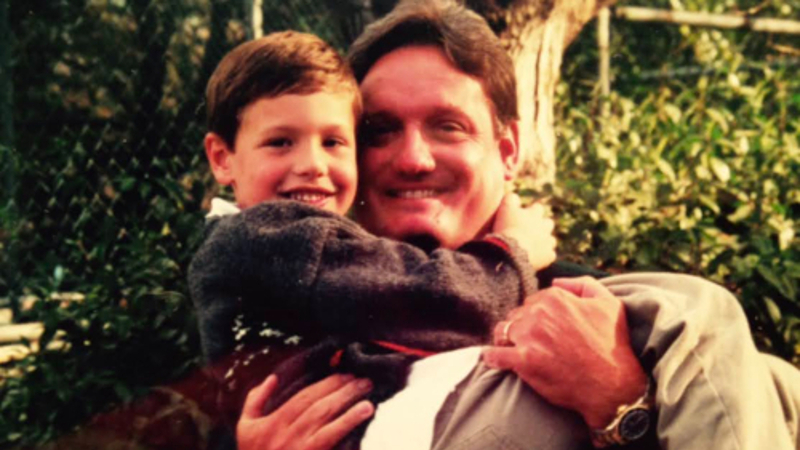

He grew up in Harrisonville, a town of fewer than 10,000 people 40 miles south of downtown Kansas City on U.S. Highway 71. His parents, both of them, became addicted to drugs when he was young. Neither returned messages for this story, but Charlotte Keck — Michael’s grandmother — remembers both doing meth with the kids in the house. Once, they burned a hole through a table and the floor underneath. Charlotte took full custody of Michael when he was in sixth grade.

Michael grew up big and strong, with a warmth and perspective that transcended his parents’ struggles. When he was just a boy, and found out his mom had been arrested again, he told Charlotte: “I hope she gets the help she needs.” Later, in high school, he was asked if he ever got angry that his parents weren’t around more.

“No,” he said. “Because that’s part of what made me who I am, and I like who I am.”

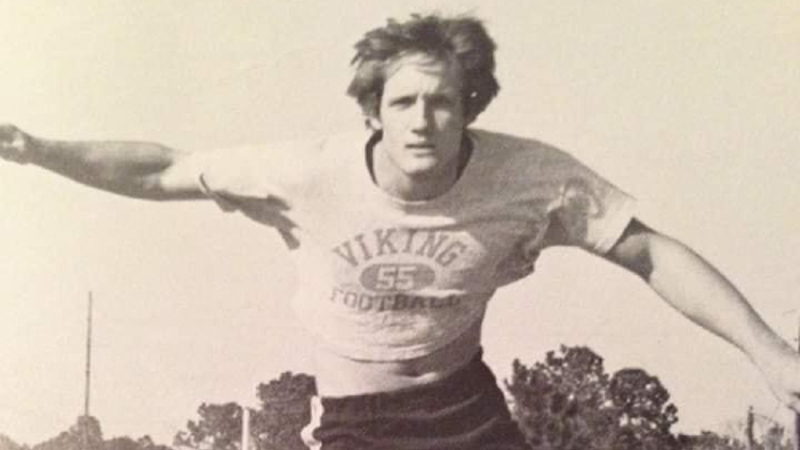

Michael was different. Growing up, he was a terrible basketball player — “the worst you ever saw,” one of his friends jokes now — but he made himself a starter on his high school team through force and determination and hours at the local park, where he studied the tendencies of all the regulars. He had asthma but refused to use an inhaler, simply running until it no longer hurt.

He was surrounded by love, even when his parents weren’t around. There was Charlotte, and Bill Collins, a judge in Harrisonville whose sons became Michael’s best friends. Michael had his own room at the Collins’ house. Michael loved them back. He made movies with his friends, broke into the school with them to lift weights, and during football season made it a point to watch as much film as possible so he could tell his teammates how to attack their next opponent. At the funeral, Charlotte remembers hearing story after story about Michael sticking up for someone.

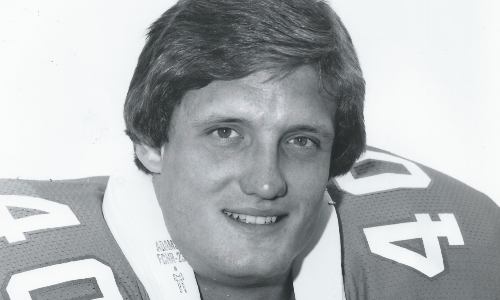

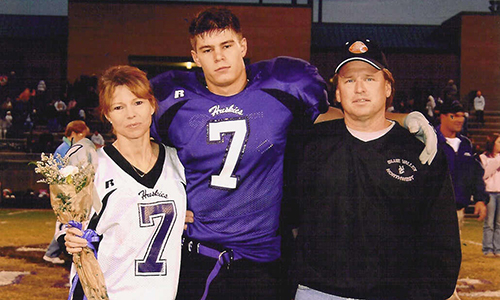

Michael was a football prodigy. He started at Harrisonville High as a freshman, and the coach soon learned that Michael gave his best at practice when another freshman was called up to varsity to work with him. Always, it was about his friends.

Around Harrisonville, they told the story of Michael’s first game, when he tackled a kid so hard that pieces of his helmet flew off. Set to a song that goes, “Here comes the BOOM,” video of that play is worn down now, they watched it so often. Later, that play would take on a darker tone.

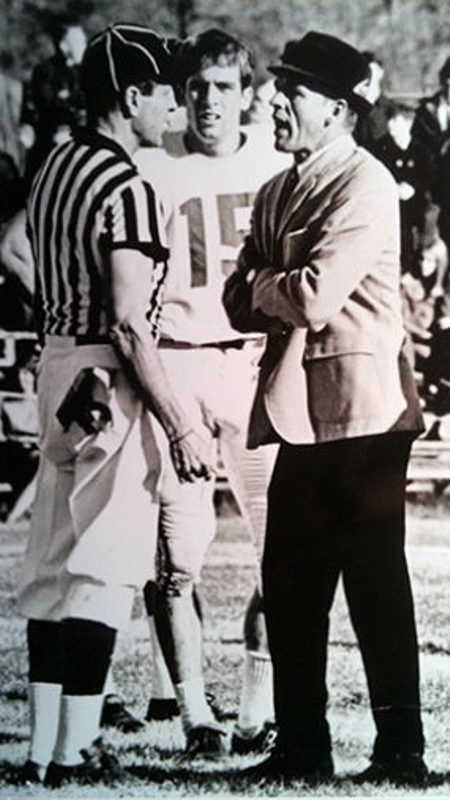

Keck was one of the brightest high school football recruits in the class of 2007. A defensive end, he sacked Cam Newton, now the star quarterback of the Carolina Panthers, in an all-star game. Alabama, Michigan, and Southern California offered scholarships. He told his grandma he wished he could divide those offers amongst his friends.

He signed with Missouri, and might’ve chosen an even smaller program if not for expectations in his hometown.

“He had the burden of carrying the hopes and dreams of a lot of Harrisonville people,” Collins said.

“He knew if he went to a smaller school, a lot of people would’ve been let down because they expected to see him on TV,” said Steven Collins, Bill’s son and Michael’s best friend. “He wasn’t cut out for (Division I football). For him, it ruined what football was about.”

Tears flowed down Michael’s cheeks as he knocked on the door of his high school football coach. This was spring of his ninth-grade year, and Michael didn’t try to hide his hurt. His girlfriend had broken up with him, and in that moment that’s all that mattered.

Fred Bouchard sat mostly in silence, comforting Michael where he could. Bouchard has coached for 30 years. He’ll never forget that conversation.

“His heart was broken,” Bouchard said. “I’ve done this a while, and there’s only five guys who’d be willing to have that conversation with their coach, and he’s the biggest bad-ass football player we ever had.”

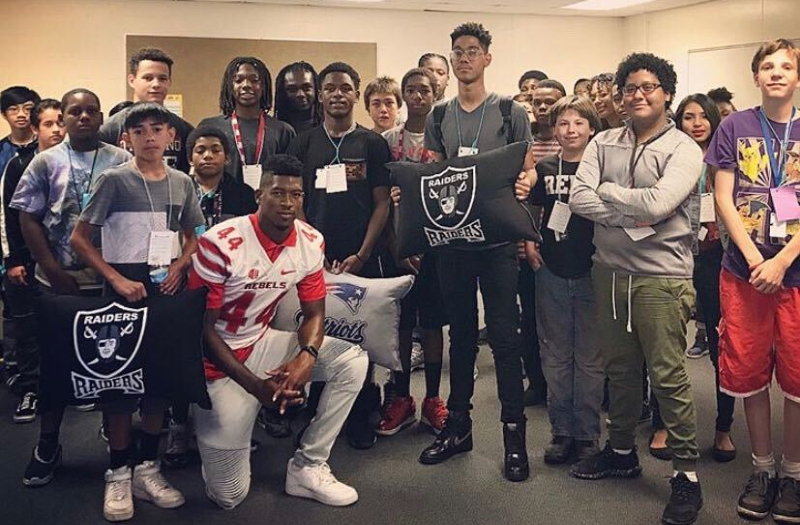

That juxtaposition — the best athlete in the school, a smart, good-looking boy completely vulnerable — was Michael. He knew pain. At lunch, he scanned the cafeteria for someone sitting alone. That’s the person Michael wanted to talk to, to ask questions of, to listen to, to maybe brighten their day. In college, he befriended a student with severe facial burn marks. Others recoiled at the sight. Michael invited him over to play video games.

“He wasn’t a saint,” said Steven Collins, Michael’s best friend. “But he was pretty close.”

Michael didn’t like football. Not at first, anyway. In grade school, long before anyone knew what kind of talent Michael had, he made excuses as to why he couldn’t play in almost every game. His ankle. His hamstring. His arm.

He cried in the middle of most games, and he said it was because something hurt. But Steven — who played with Michael through high school — came to think Michael was upset at not making a play. He hated letting down his friends.

Eventually, football became central to Michael’s life. He was the best player on the field, always, but that’s not what he liked most about it. He enjoyed competing, and that he had something to do with his friends.

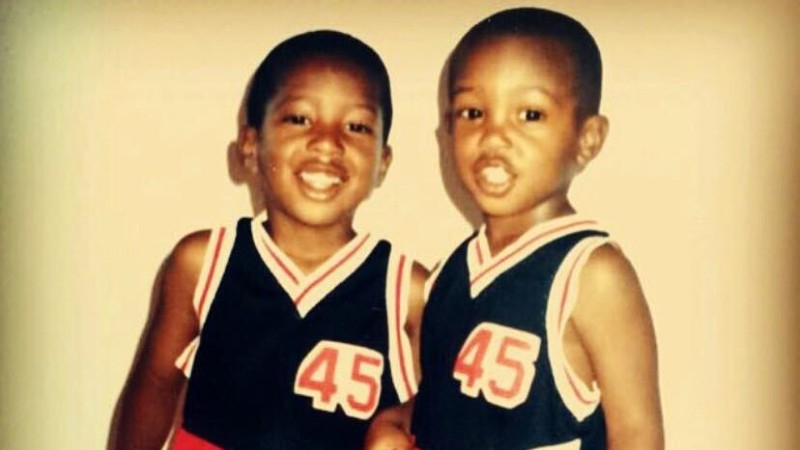

In high school, his size and athleticism caught the eye of an area AAU basketball coach. But Michael didn’t want to play without his friends, so they formed their own team. Bill Collins coached it. They bought plain white T-shirts, scribbled their numbers with a Sharpie, and called themselves the Running Rebels. The first tournament they entered, Michael dominated a kid who would later earn a Division I basketball scholarship.

Stories about Michael and sports always tended to go this way. He was drawn in because he wanted to be with his friends, then wound up being the star, which was a little awkward because that was never the point.

“That’s exactly right,” Steven said. “He was really uncomfortable with the limelight. He just loved being out with his friends.”

Michael was good enough at football that some thought he could make a career of it. Coming out of high school, he was a higher-ranked recruit than scores of guys who are now millionaires. Those were always someone else’s dreams, though. Someone else’s expectations.

Charlotte remembers asking her grandkids what they would do if they won the lottery. Michael said he would move to Hawaii, find a cottage, and buy a soda fountain.

On the surface, Mizzou looked like a terrific fit for Michael — one of the nation’s top pass-rushing prospects at one of the nation’s top schools for pass rushers.

Looking back, knowing what we know now, some from Harrisonville wonder if Michael’s brain was damaged before he even left town.

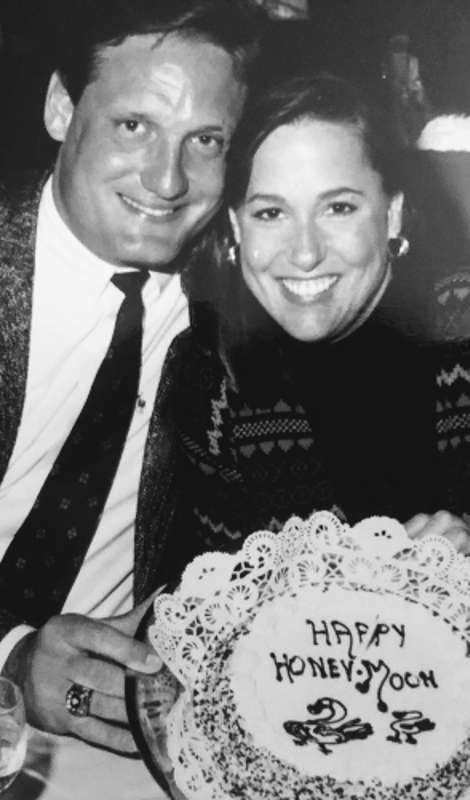

Cassandra first saw Michael in an elevator. She will never forget that moment they made eye contact, and the power they both felt. They stood there, silent, staring at each other. Cassandra could not look away.

Michael was shy, and later had a friend ask for Cassandra’s number. They hung out the next day, the two of them and Steven, with whom Michael lived after transferring from MU to Missouri State. They watched a movie. Something on Netflix; Cassandra doesn’t remember the show. What she does remember is Michael sitting on the other side of the room, and then, after a while — finally — asking if he could come sit next to her.

“We never stopped hanging out after that,” Cassandra said. “It was kind of like an addiction.”

One of Michael’s friends wonders if the first sign of trouble was Michael leaving Mizzou. He redshirted in 2007, and played one game in 2008, the whole time telling people back home that big-time football wasn’t for him. It wasn’t the decision that was surprising, but the way he left Columbia.

He just walked away. Quit. Michael never quit anything. But after a group text message to his coaches, he was gone.

“That’s not Mike,” said Zack Livingston, a friend from Harrisonville. “He regretted that. He wished he would’ve done it differently.”

As he moved on from Mizzou, Michael and Cassandra fell for each other, hard. He liked her passion, and her creativity, and her intelligence. She liked his gentleness, his work ethic and the natural way he accepted people without judgment. It was the last new relationship Michael would ever make.

He and Cassandra isolated themselves. In the beginning, it was purely choice. Love, obsession and choice. They did everything together because it felt good, it felt right, it was all they wanted. Then, slowly, rules started to change. Cassandra rearranged her life for Michael.

“I got rid of everybody,” she said, “to get his full trust.”

Michael began to forget things. His keys. His wallet. His words. Cassandra would try to complete his sentences, and Michael would get mad because it wasn’t what he was trying to say. That happened a lot. Sometimes, the anger was worse than others.

“He’d get, like, somebody else for a couple minutes,” she said. “I wouldn’t hold it against him. ‘What can we do to keep that from happening again? Let’s work as a team.’”

Cassandra’s life became largely about not upsetting Michael. If she was going to be five minutes late, she called. She broke off contact with her friends, even with her parents, because that avoided problems with him. She hung blankets over the windows, because the outside light made his head hurt. She kept their place as clean and as organized as possible, Michael’s keys and hat and coat in exactly the same place, so he would know where to find them. Anything that might start an argument, Cassandra wanted to fix before it became a problem.

They did everything together. If Michael mowed the lawn, Cassandra picked up leaves and sticks. If Cassandra washed the dishes, Michael dried them. Michael even wanted her in the room when he played video games. Once, she was in their bedroom watching TV and Michael got so mad he stormed in and slammed the set to the ground. She got used to the outbursts.

He threw a video-game controller at her, the plastic device zooming into her back and leaving a deep bruise. Sometimes, the violence was more personal. She learned how to defend herself, how to use her arms to protect her head, and that crying only made it worse.

“I would have to sit there,” she said. “Until the pain went away.”

It used to be they were alone because that’s what they wanted. More and more, it was because Michael didn’t want anyone else to see what he had become. He always apologized. He always felt bad. He knew that this wasn’t him, and Cassandra believed him.

Michael tried to work but couldn’t hold a job. He got tired quickly, and too much action made his head hurt. There was a vein on the right side of his forehead, visible his whole life, but when the pain was really bad Cassandra saw it pulsate.

The last two years were the worst. Michael had always been a bit compulsive about his hygiene, but now he’d go days without showering. He would forget to eat. He began to talk about death. He told people he was an old man in a young person’s body, and once asked his grandma why her brain worked better than his.

The violence worsened, too. Cassandra had an emergency plan. She moved the dresser in a way that she could shut the door and stiffen her legs against the furniture to keep him out. She didn’t always get there in time, so she learned to protect herself. Arms up.

“I never took it personal,” she said. “I saw everything. I was with him every day. He showed me every part of his suffering. I saw it all.”

About two months before Michael died, he and his wife talked about the first time they met. They had never done that before. Not after they started dating, not at their wedding, not even the night after they married, when they sat in that cabin with Steven and laughed all night at old stories.

They had been through so much. The love. The fights. The laughs. The tears. Justin. Toward the end, they moved to Colorado together, because maybe they just needed a change of scenery.

After all of it, Cassandra could still feel what she felt in the elevator that day. Such intensity.

She asked Michael if he remembered. He said he did. She asked what he was thinking.

“You were the most beautiful woman I ever saw,” he said.

Michael’s life became an impossible puzzle he tried to solve by himself. Doctors couldn’t help. Test results didn’t show anything. So he pulled all-nighters on the computer. He stayed up until three, four, five o’clock in the morning, drawn to the stories and videos about brain trauma and concussions.

When former NFL star Junior Seau shot himself, Michael watched the news and realized that so much of what he heard sounded like his own life. A good man prone to violent outbursts and memory loss. He saw how those stories always ended.

Michael knew death was coming. Some days, he wanted to die. Maybe then people would understand. Maybe then they would know he wasn’t making this up, or whining, or taking the same sad fall his parents had. He wanted people to know this was real.

Michael had one final wish, which he made Cassandra promise to fulfill. He wanted his brain donated for study. Something had to be wrong. The headaches. The inability to concentrate. He used to be so friendly, so thoughtful, particularly to people who needed a smile. Then, he wanted nothing to do with anyone.

Michael knew the men whose brains had betrayed them were in their 50s, their 60s, their 70s. Most had enjoyed long careers in the NFL. But he was feeling the same things they talked about. It sounded crazy, and Michael knew it.

He was in his 20s. A kid. He was once a force of nature, a package of size and strength and speed that made anything seem possible. But he played only one game at Missouri and one season at Missouri State. He remembered two hits worse than most, and figured he had undiagnosed concussions from high school, but there was no extensive history of documented injuries. How could he think his suffering was the same as those old men?

But the way he felt, how could he think anything else?

Cassandra loved Michael completely, but she was powerless through much of their relationship. Powerless to calm Michael’s rages, powerless to make him feel better in the quieter times.

Some wondered if Michael was mixed up in drugs, like his parents. Cassandra knew better than that, but she didn’t have any answers. She believed Michael, that something was wrong with his head, but without a diagnosis it was hard to be sure. Doctors never could find anything wrong. And after a while, Michael stopped going in for tests.

Then, a few months after he died on Oct. 21, 2013, the researchers called.

They had studied hundreds of brains, and never saw one like Michael Keck’s.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, commonly known as CTE, is a progressive degenerative brain disease found in athletes and soldiers and others with a history of repeated brain trauma.

The disease has taken on a greater profile in recent years as advanced forms of CTE have been found in retired pro football players. Many of them died at an early age, their final years marked by memory loss, confusion, violence, depression and, in some cases, suicide. Their symptoms often mirror dementia, though CTE can only be diagnosed after death.

CTE had been found almost solely in older players. Retired players. Seau is perhaps CTE’s highest-profile victim. He was 43, with a 20-year NFL career, when he killed himself with a gunshot to the chest.

Michael was 25. Researchers had never seen such an advanced case of CTE in a brain so young. His story has become one of the most powerful parts of presentations on the disease.

“I have to say, I was blown away,” said Ann McKee, a neuropathologist at Boston University who studied Michael’s brain. “This case still stands out to me personally. It’s a reason we do this work. A young man, in the prime of his life, newly married, had everything to look forward to. Yet, this disease is destroying his brain.”

There is no way of knowing for sure, and there is reason to believe the biggest danger is when smaller hits stack up, but Michael Keck thought the worst hit he ever took was at Missouri State.

His helmet had been malfunctioning, the pads inside losing air. Before he could fix it, he took a massive blow to the side of his head. Research shows this might be the worst way to be hit. Michael lost consciousness, and in all the years he’d played football, that never happened before.

“That was the hit he would talk about,” Cassandra said.

Michael quit football shortly after that collision, which happened around the time they found out Cassandra was pregnant. He was already having problems with his mind by then, and he wanted to be around for his son. That was in 2010. In two years, Michael had gone from a bright future at one of the nation’s top programs to quitting the sport.

“We both had tears in my office,” said Terry Allen, Keck’s coach at Missouri State. “He was a great kid. Loved to play. I loved that kid. That’s a hard deal.”

Michael walked away from the game about three years before he died. Cassandra said she is not interested in lawsuits. She wants answers, and for Michael’s suffering to push forward the understanding of CTE and potential dangers of football.

The rate of Michael’s descent, his relatively short-term exposure to the sport, and his heartbreakingly young age make his a potentially ground-breaking case for scientists and physicians studying the disease.

“It reinforces the notion that some people are very susceptible to this disease,” said McKee, the neuropathologist. “They are exposed to this in amateur sports. They don’t have to be professional athletes bashing their heads in for a living.

“Michael, for whatever reason — and we need to figure it out — was very susceptible to this. This is just not acceptable. Whatever rate this is happening in our college and high school athletes, even if it’s low, it’s an unacceptable level.”

Michael’s official cause of death was a staph infection, which caused fatal heart problems, but CTE made this tragedy inevitable. Michael’s condition was only getting worse, and his suffering deeper. A good analogy is Alzheimer’s, which doesn’t technically kill a person but makes them waste away and die from other complications, such as pneumonia.

Michael’s case brings up so many questions. So many fears. It proves that professional players — adults who make conscious decisions to play, and are well-compensated — aren’t the only ones at risk. Perhaps researchers can learn something specific about Michael’s brain, or his exposure, that caused the disease to spread so rapidly.

Maybe Michael’s suffering — and the pain it caused Cassandra and others — can lead to new knowledge that might help someone else.

“I need to do this for Michael,” Cassandra said. “He wanted so badly for people to know about this. He did so much research on it. It can’t stop there.”

The first thing you see when you walk into Cassandra Keck’s house is a picture of Justin, smiling as wide and bright as a little boy is capable of smiling. If you knew Michael at all, the resemblance is stunning.

It’s not just the face, either. Cassandra remembers Michael and Justin standing in the bathroom, both without shirts, waiting for the water to warm up for a bath. The head shape. Their hair. The way their necks became shoulders. It was identical. Even now, she laughs when she tells the story.

Justin and Michael had their own language. Mmmmm, was hungry. A cough meant Justin was thirsty. He cried in his crib, and Michael knew that meant he wanted to sleep with a toy. Those are Cassandra’s memories, and they are good memories. They are great memories. This, too, is part of what she wants to pass along.

“Justin will tell kids at school, ‘My dad died,’ ” Cassandra said. “He’ll say, ‘He got sick.’”

She thinks all the time about what she wants Justin to know about his father. At the funeral, she gave everyone pens and paper and asked them to write down their memories of Michael. She’s saving everything, and when he’s ready, Cassandra will share it all with Justin.

She wants him to know his dad was loyal, and that he was always there for people, no matter what, even if they’d done something to hurt him before. She wants Justin to know his dad worked hard, freakishly hard, to make what he wanted a reality. She wants Justin to know his dad never complained, even when he had plenty of reason to. More than anything else, she wants Justin to know how much his dad cared, and wanted a better life for his son, one without the uncertainty and ups and downs he went through.

On the wall at Charlotte’s house is a picture of the 2006 Harrisonville High football team. That team was loaded, going undefeated and winning the state championship game by five touchdowns. Their best player was Michael, who borrowed a suit and tie for the team picture and sat at the end of a row. That season was the last time he was happy on the football field, the last time he was able to play with his friends.

Every now and then, Justin points at the picture.

“Dad,” he says. “Dad dead.”

Then he points higher.

“Yeah. He’s up there now.”