Louis Kelley

Harold Keohane

Kenny Keys

Kendal Keys woke up on July 26, 2018, and said enough was enough. He had been trying to see his older brother Kenny for months but the two failed to connect despite both being in Las Vegas. This time, he didn’t give Kenny a choice – he picked him up and drove to their dad Kenneth Sr.’s place for dinner.

With Kenny in tow, Kendal blasted Chance the Rapper’s “Blessings.” Kenny was dozing off, but Kendal couldn’t stop smiling.

“I was just happy because he was with me,” Kendal remembers.

At one point on the drive, Kendal asked Kenny a simple question. Kenny delivered a completely incomprehensible answer. Kendal’s heart sank. He had seen this before.

The two arrived at their dad’s place and Kendal walked into the bathroom and looked himself in the mirror. We can do this, he told himself. It was too late to take Kenny back to his psychiatrist that night, but he would plan to take him there first thing in the morning.

Kenneth Sr., Kenny, and Kendal enjoyed each other’s company over dinner. Kenny and Kendal were back laughing at and with each other like they had their whole lives. Kendal offered to step out and get some water bottles for everyone, hoping to get Kenny back in the car so they could discuss the need for an appointment the next day. Instead, Kenneth Sr. offered to come along and Kenny opted to stay behind.

At Walmart, Kendal and Kenneth Sr. ran into a family friend who told them to say hello to Kenny for her. Father and son both remarked on the breathtaking sunset above the mountainous Las Vegas horizon on the drive home.

When they opened the door back at Kenneth Sr.’s place, Kenny wasn’t where he’d been when they left.

“As soon as I didn’t see him on the couch, I just knew he was dead,” Kendal said. “I didn’t know how but I just knew he was gone.”

“You only got one Kenny.”

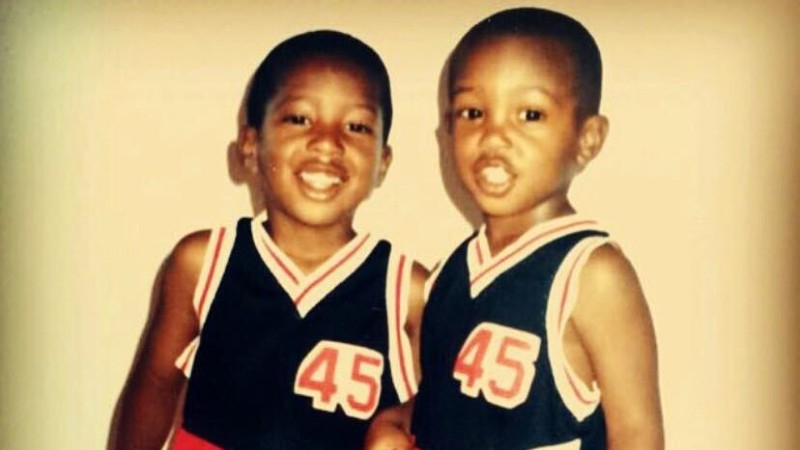

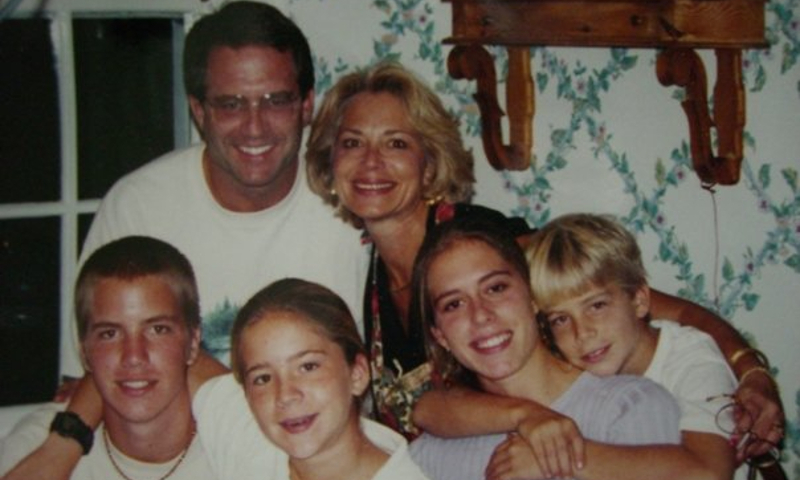

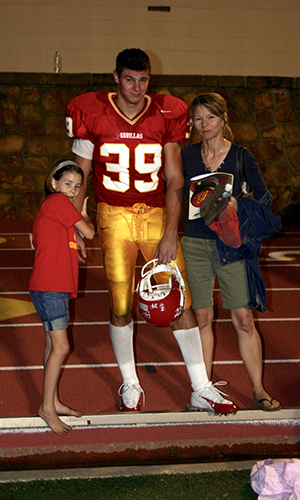

Kenny Keys, Jr. was born on February 25, 1993, to Kenneth Keys Sr. and Syvonne McNair in San Diego, California.

Kenneth Sr. grew up in Florida as one of 13 children. He loved watching his Miami Dolphins on Sundays but Kenny’s energy as a toddler often got in the way.

“I would make him run down the hallway,” said Kenneth Sr. “When I’d say, ‘Go!’ he would run down the hallway and around the living room. It was the only way to tire him out and he’d just fall asleep.”

From a young age, Kenny exhibited a coolness with everything he did. People gravitated to him.

“Teachers would tell me how Kenny had a smile that could stop a bus,” Kenneth Sr. said.

Kenneth Sr. was a correctional officer for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and then a prison counselor. He often made visits to school to speak to students. Kenneth Sr. was a former college basketball player with the height to prove it. Kenny used his dad’s height to manufacture an autograph line full of kids who were convinced his dad played in the NBA.

Kenny’s mother Syvonne also worked in law enforcement. They called Kenny “The Judge” because he could always see right from wrong and settle disputes between his siblings, Kendal and Kaitlyn. Kendal was born less than a year after Kenny and then Kaitlyn came five years later, in 1999.

Kendal had the benefit of following Kenny’s lead and the curse of trying to fill his shoes.

“He was the complete role model,” Kendal said. “He knew that I needed guidance and everywhere I went he always told me where to go.”

“Effortlessly cool.”

The Keys boys were two peas in a pod, always playing sports together. Kenny usually won and he’d let Kendal know all about it, which led to a near-constant cycle of playing, fighting, and making up.

Throughout life, it wasn’t just losing to Kenny that irked Kendal. It was how easily everything came to Kenny.

“He didn’t even want to be prom king and he won prom king,” Kendal said. “He didn’t have to try. I was the one who had to try all the time to be liked or whatever.”

The boys ran track, played basketball, and starting in 2006, played middle school football. It was there that Kenny developed a reputation for laying out heavy hits to opposing receivers and nonchalantly walking away from the damage afterwards.

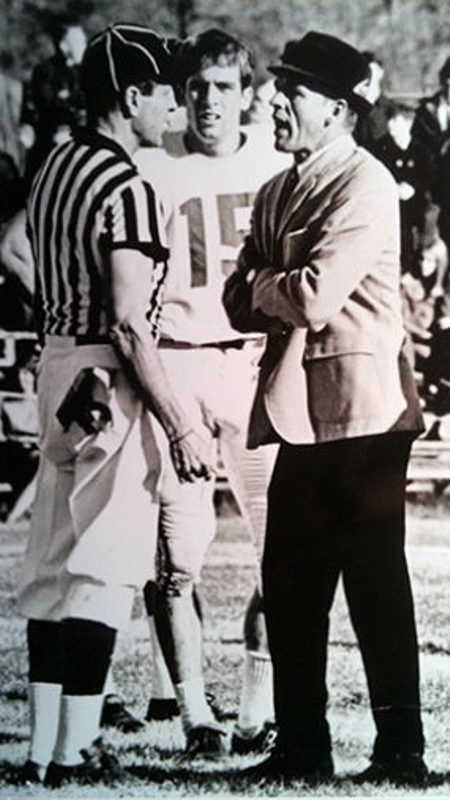

At Helix High School, Kenny continued to star in track and basketball and didn’t play football until he was a senior. At tryouts that year, the coaches challenged him with a one-on-one drill against one of the team’s biggest players. Kenny knocked him out cold. With Kenny as a starting safety, Helix went 12-1. Kenny’s play in just one high school season earned him a Division I scholarship offer from UNLV.

44 Magnum

In his first football season at UNLV, Kenny picked up where he left off at Helix. He appeared in all 13 games, starting five, recorded 45 tackles and two interceptions wearing No. 44 for the Rebels. The hard hits continued and earned him a new nickname. “The Judge” was now “44 Magnum.”

Kenny made the Dean’s List that year and returned to Helix High to catch one of Kendal’s games. Kendal knew his big brother was in the stands and caught the first touchdown of his career. As he came off the field, Kendal was surprised to see Kenny come all the way down to the sideline to celebrate.

“He wanted us all to better ourselves,” Kendal said. “He wanted everyone to be successful. He didn’t hate on anybody.”

Kendal blazed his own trail as a receiver at Helix and earned the attention of college scouts. Initially, he had no interest in playing with Kenny at UNLV. He was more attracted to the bigger stage and bluer turf of Boise State and signed to play there in 2013. Local papers in San Diego wrote about the impending matchup of the Keys brothers in the Mountain West Conference.

But Kendal’s career in Boise was over before it started. After enrolling in fall 2013, he was expelled from the school. The expulsion marred Kendal’s chances of enrolling elsewhere, but Kenny convinced the UNLV coaches that Kendal was more than his mistakes. They took Kenny’s word and Kendal signed with UNLV, thrilled with the opportunity to play college football with his big brother.

With Kendal now set to move in with Kenny, Syvonne warned Kendal that she had noticed something was off with his brother. At first, Kendal didn’t see what she was talking about. If anything, Kenny seemed like he was back at Helix. Everyone loved him and once again, Kenny was showing Kendal the ropes on campus.

But slowly, Kendal noticed what his mom was describing. Typically, Kendal couldn’t be around Kenny for more than ten minutes without busting out laughing at something he did or said. But this Kenny was quiet and more distant. Kendal frequently caught him staring off into nothing.

The behavior affected his standing in school and on the UNLV team. Kenny was routinely late or completely absent from spring and fall camp. He barely played his sophomore season.

Kenny would also say bizarre and alarming things to Kendal. He once joked that Kendal should drink Drano with him. Fearful Kenny would hurt himself, Kendal never let his brother out of his sight. But once, after Kendal took a nap, he woke up to find Kenny gone. He returned three hours later. When asked where he was, Kenny flatly told Kendal he went to the Vegas strip and considered jumping off a building.

“We gotta get you out of here.”

Kendal knew something was wrong but shouldered the burden of trying to fix his brother. He wouldn’t tell his mom everything because it would have led to dozens of calls a day. He wouldn’t tell Kenneth Sr. for fear of disappointing the father who cherished his children’s successes.

“It was like we were always the trophies,” Kendal said. “We were always on a sports team and his friends would come to see us. So, we felt like we didn’t want to ruin that.”

Kenneth Sr. tried to connect with Kenny, but his calls went unanswered. Kendal always picked up but kept details about Kenny to a minimum. In October 2013, Kenny’s internal battle reached a breaking point. He finally called his father back.

“Dad, I need your help,” Kenny said.

Kenny had just left a psychiatric hospital he was admitted to after trying to take his life.

Kenneth Sr. started corresponding with members of the UNLV coaching staff. He set a meeting with UNLV head coach Bobby Hauck in November 2013 to discuss Kenny’s progress. Kenneth Sr. asked his sons to join him for the meeting, but only Kendal showed up. Hauck informed Sr. that Kenny completely flunked out of the fall term at UNLV. He could maintain his scholarship if he returned to school in January.

Kendal had to tell his father that Kenny missed the meeting because he was in a psychiatric hospital again after making a second attempt on his life.

Kenneth Sr. took his rental car to the hospital to find a heavily sedated Kenny. Kenneth Sr. couldn’t stand to see his beloved son with the bus-stopping smile medicated to the point of looking like a zombie. He combed Kenny’s hair and promised to do what it took to get him out of the hospital.

Kenny was on heavy doses of medications to keep him calm. At the facility, doctors would test different drugs on Kenny until they found what worked. Kenneth Sr. took Kenny to all his meetings and visited him frequently throughout his stay. He was released in January 2014.

Kenny was diagnosed with major depressive disorder and psychosis, as well as marijuana and amphetamine abuse. Psychiatrists concluded Kenny’s sudden onset of symptoms may have been triggered by marijuana use and THC.

He made it back before Hauck’s deadline, but UNLV and the NCAA would have to see Kenny’s psychiatry report before clearing him to play. Kenneth Sr. assumed there was little chance they would deem Kenny eligible to keep playing. But they did.

“If they only looked in our eyes.”

With Kenny out of the hospital, Kendal had his brother back. Kenny was quieter than before but more importantly, stable. As his dosage of medication lessened, Kendal saw someone closer to the old Kenny return. In conversations about the last few months, Kenny didn’t remember the suicide attempts or any of the alarming things he said to Kendal.

With Kenny cleared to play, the Keys brothers could finally share the same field at UNLV. On Kendal’s first day of practice in spring 2014, none of UNLV’s receivers were eager to step up to Kenny in a one-on-one drill. Kendal never balked at an opportunity to prove himself and volunteered. He was quickly humbled by his big brother. In another drill, Kendal caught a pass and was running across the middle of the field before being stripped from behind. Kendal knew how much his coaches hated fumbling and was ready to blow up on whoever stripped him. But he turned around to see a smiling Kenny.

“I’ll never forget that,” Kendal said. “My brother is really out here. We have the same parents, now we’re on the same team.”

Their first season together offered a glimpse at a bright future. Kendal broke on the scene with 24 catches as a true freshman and Kenny recorded 42 tackles, many worthy of the “44 Magnum” moniker.

Kenny suffered two diagnosed concussions in his football career, and his family thinks many undiagnosed ones as well. He often said he finished games without knowing what half the game was in or where he was. Not only did Kenny’s nonchalant nature after big hits potentially hide concussion signs, Kenny also learned from a teammate to keep his helmet on when he was on the sideline so nobody could see his eyes.

Kenny saw a psychologist with some frequency since he returned to UNLV in 2014. But in his junior year, Kenny called his dad again.

“Dad I feel like I’m hurting everybody,” Kenny said.

Kenny again expressed thoughts of self-harm. Kenneth Sr. insisted there were countless people who loved Kenny and needed him to be strong.

Despite his unquestioned ability, Kendal says the coaching staff didn’t love giving Kenny playing time. He was routinely outworked in practice and in the weight room and coaches gave starting jobs to other players. But when UNLV went down in games, Sr. says Kenny was brought in to clean up the mess. On multiple occasions he led the team in tackles despite not starting the game.

Kenny’s fifth and final season at UNLV in 2016 was his brightest. He recorded 66 tackles and five pass deflections.

The 2017 NFL Draft came and went without Kenny’s name getting called. An AFC East team was interested in signing him as an undrafted free agent, but Kenny was still recovering from shoulder surgery and the team passed on signing him for the time being.

While Kenny wouldn’t be playing professional football, he had plenty to celebrate. After high school, Kenneth Sr. challenged Kenny. Plenty of people go to college, but the real achievement was graduating. After Kenny graduated from UNLV, Kenny went straight to his father with his degree.

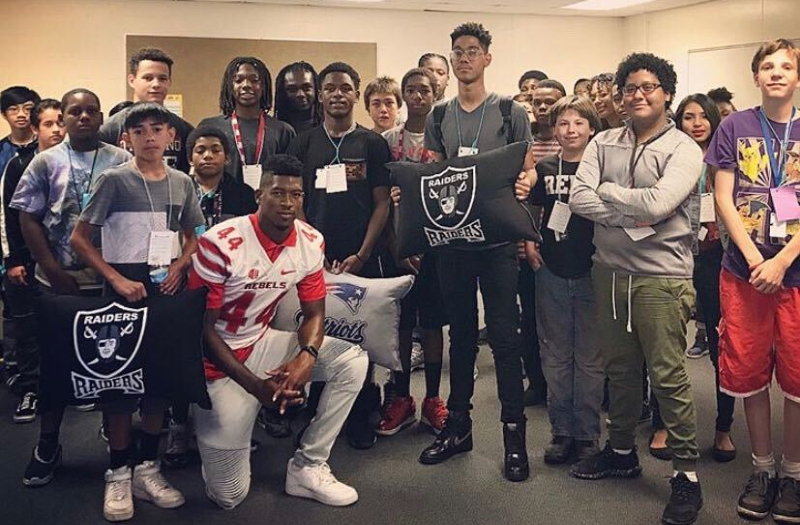

Kenny studied education and sociology. He had ambitions of being a mentor for the next generation and was a beloved volunteer at Paradise Elementary School in Las Vegas.

Kenny was frustrated at not being able to find a job immediately after graduating. He worked at a warehouse and stayed in shape for a potential shot at the NFL. He got a boxer named Cali who was glued to his side. Kenneth Sr. moved to Vegas in May 2017 and noticed Kenny seemed down at times, but he was always talkative and invigorated whenever he was around Cali.

One afternoon in July 2018, Sr. came by the warehouse to deliver Kenny’s favorite homemade meal of collard greens, cornbread, and ribs. When he dropped off the food, Sr. noticed Kenny looked drained.

Sunset

Kenneth Sr. and Kendal will never forget the sunset they saw on their drive back to Kenneth Sr.’s home on Thursday, July 26, 2018 and the memory it triggers.

They arrived back that evening with bottles of water and the Pepsi Kenny asked for. When Kenny wasn’t immediately in sight upon arrival, Kenneth Sr. assumed he was using his master bathroom on the left side of the house. Kendal had an ominous feeling about where Kenny was and made a beeline to the bedrooms on the right side.

Moments later, Kendal left the room and yelled in agony to his father. Kenny had taken his life. He was 25 years old.

“I could see the pain that he was going through.”

Sr. sought answers after Kenny took his life. When Kenny’s toxicology report came back negative, he found relief in knowing Kenny did not have any drugs or alcohol in his system upon his death.

His search for answers then led him to the UNITE Brain Bank, when a member of UNLV’s athletic department gave Kendal a tip for Kenneth Sr. to call the number for brain donation. Sr. obliged.

Before the tip, the family hadn’t considered how Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) may have played a role in Kenny’s story. CTE is a degenerative brain disease found in athletes, military Veterans and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, performed the pathology report on Kenny’s brain. She detailed her findings to the Keys family on a call. Kenny had Stage 1 (of 4) CTE.

“The way that Dr. McKee explained it, I could see the pain that he was experiencing,” Kenneth Sr. said. “That doesn’t explain why he did what he did, but I can see why he was hurting.”

Early symptoms of CTE typically appear in a patient’s 20’s or 30’s and can include depression, aggression, paranoia, impulse control problems, and suicidal thoughts. The connection between CTE and suicidality is still unclear to researchers but it is part of ongoing research at the UNITE Brain Bank. Research has shown a link, though, between concussion and suicide risk. One study found those who suffer a concussion are twice as likely to take their own lives.

On their last drive together, Kenny told Kendal how excited he was to watch him finish his football career at UNLV. With a year of eligibility left, Kendal chose to keep playing. He joined the Rebels at fall camp a week after Kenny’s death.

“Kenny is suffering that much and in that much pain, but he’s thinking about me playing?” said Kendal. “I needed to get back out there.”

They played different positions, but Kendal exhibited a similar physicality and reckless abandon to Kenny. After Kenny was diagnosed with CTE, Kendal realized how important it was for football players to take care of their brains.

“Speak up about concussions,” Kendal said. “If you are feeling some type of way about your head, don’t let your ego get in the way. Because it could cost you your life.”

Kenneth Sr. echoed those thoughts with a message to parents.

“After a couple of concussions, you want to err on the side of caution,” Kenneth Sr. said. “Go ahead and remove them from that sport. Better to have them here than to not have them here.”

Kenny meant a lot to so many. Many of his former teammates chose to memorialize him through tattoos and custom jewelry.

Torry McTyer played in the defensive backfield and was good friends with Kenny at UNLV. He was in training camp with the Miami Dolphins when he heard Kenny took his life. In response, McTyer and his family raised thousands of dollars for the Keys family. In the 2018 NFL season’s “My Cause, My Cleats” week, McTyer chose suicide prevention as his cause with cleats that said, “In Memory of Kenny Keys.”

“You always feel like you could have done something different,” McTyer said in a story for MiamiDolphins.com. “It’s a helpless feeling. But I want people to know who Kenny Keys is. I want people to realize that things like this are happening everywhere and they can be prevented.”

After she lost two of her children, Kenneth Sr.’s mother once told him there was no pain like losing a child. He now can understand his mother’s grief. He has focused his attention on trying to protect other parents from his tragedy.

“I spent 26 years saving people’s lives and I couldn’t save my own kid,” Kenneth Sr. said. “I’ve got to help somebody. If I could just help one kid, save just one kid’s life, or educate some parents and let them know how serious these concussions are then I’ll be good with that.”

Kendal internalized guilt for Kenny’s suicide for a long time. He dreams about Kenny nearly every night, always imagining the two of them laughing and being goofy together.

He wants to honor Kenny’s legacy by encouraging other athletes to seek mental health resources and be honest about their symptoms. He implores anyone struggling to reach out and when they do see a mental health professional, to bring someone with them who can speak to their issues and eliminate the chances of getting misdiagnosed.

“When you go get help, don’t go in there knowing or demanding or trying to think you can do it yourself,” Kendal said. “Let the professionals do what they’re paid to do.”

Kendal has joined our roster of mentors for the CLF HelpLine. He hopes to be a resource for other football players who are battling the effects of concussion or struggling with their mental health.

When Kenny left the psychiatric hospital in winter 2013, he gave his Helix High letterman’s jacket to his dad.

After Kenny died, Kenneth Sr. found the jacket again. In one of the pockets, Kenneth discovered a folded handwritten note Kenny wrote while in the hospital thanking his dad for everything he had done for him. Kenneth Sr. He holds the note and the memories of Kenny tight.

“He was a good kid, man,” said Kenneth Sr. “He was special.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org.

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Michael King

For many years, he spent his Friday nights on the sidelines of local high school football fields where he cared for the athletes, and our home was a virtual walk-in clinic where young athletes and their parents, many of whom could not afford formal medical treatment, were given the care they needed. Our Dad was an “old school” doctor, the kind who visits his patients at their homes and spends extra time with them in the office, explaining the root cause of their injuries and making them feel safe in his skilled and gentle hands.

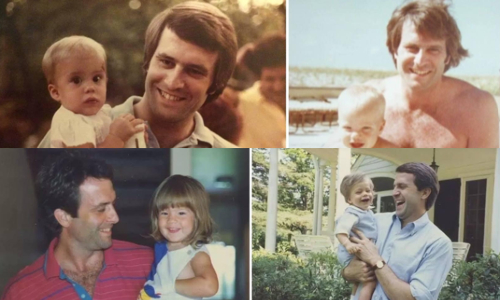

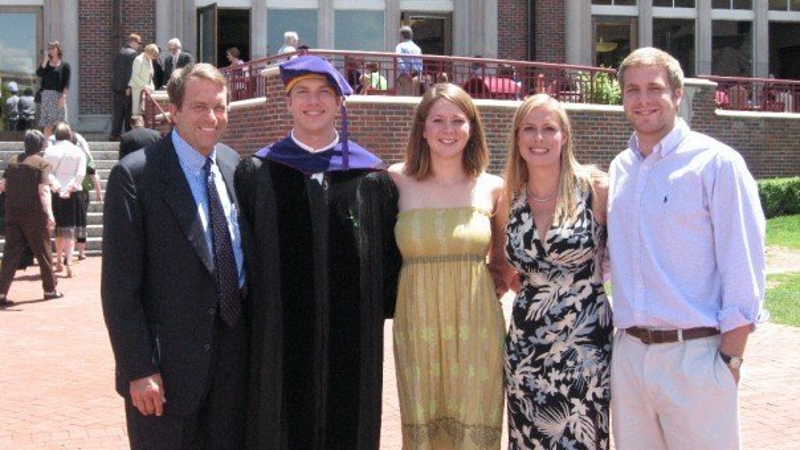

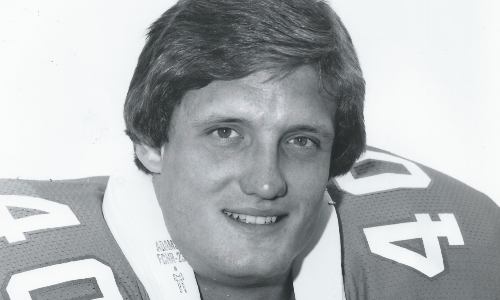

Dr. Michael King, father, husband and surgeon, took his own life at his home in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, at the age of 65. Our Dad was a beloved orthopedic surgeon and a selfless teacher. For many years, he spent his Friday nights on the sidelines of local high school football fields where he cared for the athletes, and our home was a virtual walk-in clinic where young athletes and their parents, many of whom could not afford formal medical treatment, were given the care they needed. Our Dad was an “old school” doctor, the kind who visits his patients at their homes and spends extra time with them in the office, explaining the root cause of their injuries and making them feel safe in his skilled and gentle hands.

Our Dad had been a great athlete in his youth. He excelled in basketball, swimming and football, and was the star quarterback for his high school team, Page High School in Greensboro, NC. He then went on to be the quarterback and captain of the football team at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia and graduated with a degree in Political Science in 1969. By the time he was in his late-20s and in medical school at UNC-Chapel Hill, his body was already starting to break down. Over the next several decades, due to past sports injuries and worsening osteoarthritis, he became the real life bionic man—with double shoulder and knee replacements, a hip replacement and a fused ankle.

Our Dad loved his family. He is survived by his wife Donna, his children Katie, Mike, Marylynn and Alex, step-daughter Meagan Ferrell, his former wife and dear friend Susan Gordon King, and one brother and three sisters. Our Dad was most at peace tending to his garden where he taught many life lessons and spent countless hours with Donna. He loved talking with his children, of whom he was extremely proud, and sharing in their achievements. He was an accomplished artist and craftsman, talents which he often used to create personalized gifts for family and friends. He was also an avid reader and aficionado of history and politics. Our Dad believed strongly in the importance of faith, family, education and hard work, all of which he instilled in his children.

Our Dad suffered from depression for most of our lives. It was just part of who he was and we loved him anyway. At times it was unbelievably frustrating, as his depression was expressed through anger, impatience and his demand for perfection from all those around him. Other times his depression made him distant and weepy. We each sought to help him in our own ways, with letters, phone calls and visits home to remind him how much he was loved. By early 2011 our Dad’s osteoarthritis became so severe that he could no longer perform surgeries. His fingers were extremely swollen and stiff and he needed help doing the most basic things around the house. He struggled mightily with the thought that things were only going to get worse, and in his increasingly debilitated state, he felt as though he had nothing more to give.

We know that our Dad suffered many concussions during his years as a quarterback and he spoke often of the effect those head injuries may have had on his mental and emotional state. When he died we knew we wanted to donate his brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation. We are so thankful for the dedication of Dr. McKee, Dr. Stern, Chris Nowinski and all of the staff at the Concussion Legacy Foundation for their work on CTE. Our Dad would be honored to be part of such a renowned program. We miss him dearly but find peace knowing he is no longer suffering and comfort that his pain may help others.

Alex, the youngest of the four King children, had a very successful college career as a punter both while an undergraduate at Duke University and as a graduate student at the University of Texas. At UT, Alex wore our Dad’s old number, Number 15.

Click here to read an article about Michael published in the Winston Salem Journal.

Michael Kovac

Kyle Krull

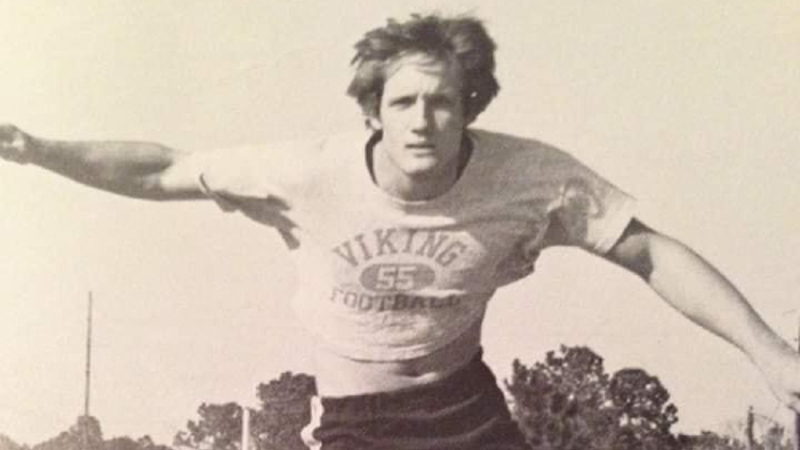

There is a reason his nickname was scud. The opposing offense rarely saw him coming. And if they did, it was too late. Kyle Krull could hit anyone on a football field and hit them hard. He was an aggressive linebacker with a natural eye for the game. His success was equal parts skill and strong will. Mediocre was not in his vocabulary. If he was going to do something, he was going to do it better than anyone else.

Kyle was the teammate everyone wanted to be around. As funny as he was kind. The team captain who made everyone feel welcome. If someone was eating alone in the cafeteria, Kyle would be the first person to pull up a chair.

His talent and charisma earned him the spot he’d always dreamed of – a Division I football scholarship. Kyle would play one season for the Western Illinois University Leathernecks before concussions cut his career short. In the years that followed Kyle began to question if the game that encapsulated his identity for most of his life could also be the source of so much of his pain.

By all accounts, he was a thriving 25-year-old living and working in downtown Chicago. But inside, he was fighting symptoms that scared him. Headaches that would never stop. Anger triggered by anything and anyone. Difficulty concentrating on the simplest tasks. Sleep was hard to come by. Kyle knew something was wrong, but he didn’t know how to fix it.

He went out with friends that Friday night like he always did. He was his usual outgoing, life of the party self. Then he went home. Kyle Krull took his life early the next morning, on June 1, 2019. He was found three days later.

Eat, sleep, breathe football

Kyle Krull was always on the go. There wasn’t a sport he wouldn’t try, or an activity he wasn’t into.

“The kid was moving and grooving,” Meg Campion, Kyle’s older sister said. “He did everything outside that you could imagine. Wakeboarding, snowboarding, skateboarding, rollerblading, basketball, hockey, lacrosse. You name it.”

Then there was football. Kyle had his sights set on the gridiron from a young age. He wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps and play in college. Any linebacker on the Chicago Bears was his hero, and he couldn’t wait to experience the brotherhood of a team like he watched over and over again in movies like Remember the Titans and Friday Night Lights.

It was no surprise once Kyle suited up for his first Pee Wee league game in fifth grade that he was a star. And he worked hard at it. He became a student of the game and studied diligently. He took every opportunity to perfect his craft. But that hard work didn’t come without frustrations. By his early teenage years, a different Kyle started to subtly emerge.

“He was this bright ray of sunshine for everyone around him,” Campion said. “He was the team leader always looking out for others but then he would come home and collapse because it was so hard to keep up. We rarely saw that side of him, but he would have outbursts and become very angry and say hurtful things.”

The game took its toll on Kyle, no matter how hard he worked to push through the pain or hide his brain injuries. In total, Campion thinks Kyle suffered upwards of 30 concussions.

“I remember him coming home from football camp and just sitting in a dark room saying, ‘I’m just so dizzy,’” Campion said. “But I had no idea what was really going on, I thought a concussion was just when you threw up after a head injury.”

In college, Kyle continued to take damaging blows to the head. After one season at WIU, he lost his love for the game and knew he had to be done.

“After that freshman season Kyle realized if he kept playing it would ruin his body and his brain,” Campion said. “He said, ‘That’s it. I’m not going to be a punching bag.’ We thought he was safe, but it turns out there are lasting effects there that we didn’t know about.”

Looking for a fresh start, Kyle transferred to Western Michigan University where he thrived. He adjusted well to life without pads and cleats and found a great group of friends. He excelled in the classroom and graduated from the business school with honors.

Cascade of symptoms

Kyle started his post-college career back in the Chicago area working for a third-party logistics company. He moved just four blocks away from his big sister. They did everything together, spending days and nights filled with the type of laughter that makes your abs sore.

“He had this way about him of making any situation hysterical,” Campion said. “He just knew how to bring such light and joy wherever he went.”

While Kyle continued to shine socially, he struggled cognitively. Things were harder than they used to be.

“It was tough for him to concentrate,” Campion said. “He had to write everything down because he couldn’t remember anything. I watched him struggle to learn new card games or retain any new information at all.”

He also battled relentless headaches, and Campion remembers him feeling tired all the time no matter how much sleep he had the night before or caffeine he was able to pound throughout the day. An athlete at his core, Kyle was especially concerned when he started having a hard time with his balance. He went to doctors for an answer. He was determined to figure out what was wrong with him on his own and refused any help from family. Because of that, Campion can’t be sure what the neurologists told her little brother, but she does know he thought about Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) often.

“One day he told me he wanted his brain to go to CTE research,” Campion said. “He said he didn’t want others to feel the way he did.”

That conversation triggered a turning point for Campion. She started to do her own research on CTE and realized her brother may be hiding serious pain behind his signature smile.

In the months that followed, Kyle became more irritable. Anything could set him off. He struggled with social anxiety and there was a sense of sadness about him. Still, Campion was comforted knowing he was seeking help and working to get better. He went to therapy weekly.

The night before Kyle Krull’s death he went out with friends. He appeared to be his normal, friendly self.

“I always tell people that Kyle was the better version of who I am,” Campion said. “He was who I wanted to be in social situations. How happy-go-lucky he was and how he made everyone feel instantly welcome. When he was talking to someone, he had this ability to make them feel like they were the most exciting thing in the room and he genuinely wanted to hear their story. He loved going into a room full of people he didn’t know – but then he also had this darker side that a lot of people didn’t see.”

The next morning, he died by suicide in his home. Kyle Krull was 25 years old.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health suicide is a complex public health concern, and there is no single cause. Suicide most often occurs when stressors and health issues converge to create an experience of hopelessness and despair.

Finding answers

After Kyle’s death, his family scoured his computer for any sort of clue. They found every single tab he left pulled up pointing to things he could try to help improve his symptoms. He was always looking for ways to get better.

It was an easy decision for Kyle’s family to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. It’s what he wanted.

“The Kyle we knew and loved didn’t do this, something else inside him did,” Campion said. “He knew something was wrong so we want to do everything we can to figure out what it was. We want to know the name for what did this to our family and what changed our lives forever.”

Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank found Stage 1 CTE in Kyle Krull’s brain. Campion is now dedicated to educating others about CTE and making sure everyone knows it is a preventable disease.

An October 2019 study by Boston University researchers found for every year of tackle football played, a person’s risk of developing CTE increases by 30 percent. For every 2.6 years of play, the risk of developing CTE doubles. Knowing that crucial data, Campion hopes to see youth tackle football banned, and all athletes under age 14 playing flag football instead.

She also wants people to understand the complexity of depression. Not everyone has the same symptoms. Kyle rarely seemed sad. He was never withdrawn or isolated. She says it’s critical for people to understand somebody who is your best friend could be struggling and you might not know.

“I get this feeling of nausea that washes over me that I don’t have a brother anymore,” Campion said. “You never think about your future without your sibling and you kind of take advantage of them being in the background of your life or being in your life in general until they’re not there. There isn’t a moment that goes by that I don’t think of him and there are so many times where it’s uncomfortable to talk about with other people, but I can either use it as an opportunity to shut down or I can use it as an opportunity to educate people about what happened and share Kyle’s story so nobody else experiences the same pain.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Robert W. Kurzu

Dear 25-year-old me,

You have just embarked upon your professional career, but you are impatient to find true love. Typical you. Wanting all the answers, you accompany some friends to a well-known futurist in Chicago to see if you can learn what your life will hold for you. The seer spends more time with you than with your friends, says you are powerful and strong, and reveals you will have a fantastic career. When you ask about love, she shares you will marry the love of your life – a man with the initials BK who is your intellectual equal, who is also powerful and strong, a gifted athlete and a bit of a cowboy. She promises you will have two beautiful children and a magical, happy life together. When you inquire if you will be married forever, her face clouds and she simply responds that she sees lots of confusion; she sees your handsome husband in a daze and walking alone along his property line.

She could tell me no more, but it was all true.

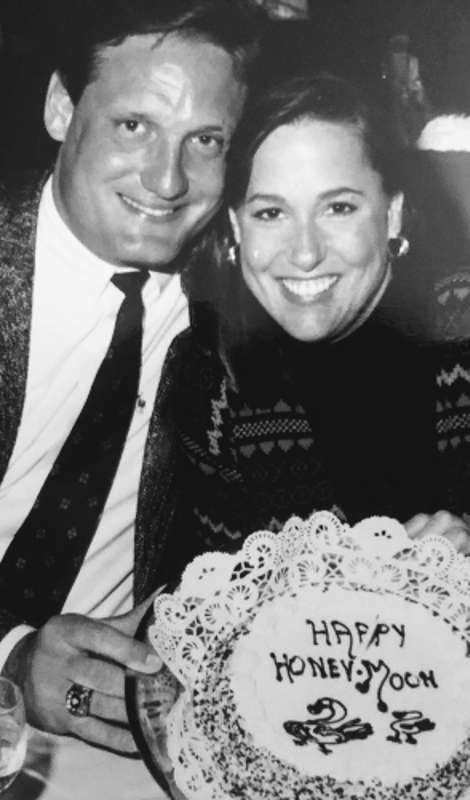

It takes another four years for Bob Kurzu, Mr. BK, to walk into your life and steal your heart. You’ve just moved to New York and are on a blind date in Little Italy with a group of people when the most handsome man you have ever seen walks into the restaurant, with a blonde on each arm. Immediately you disregard him as “just another pretty face” – until later you learn he had been unceremoniously dumped by a woman who was seated at your table, and he wanted to make an entrance. It doesn’t take long for you to realize this is a funny, kind, and self-deprecating man.

Later, when you are set up to go on a date with Bob, you begin to appreciate his extraordinary intellect and accomplishments. You discover he is a former scholarship athlete – a football player for the University of Florida. But more impressively he is a business manager for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute where he supports several Nobel Laureates and their scientific discovery at Columbia University, Rockefeller University, and NYU.

Beautiful and brilliant.

Whirlwind romance doesn’t even come close to describing your courtship. You’ve never been so in sync with anyone before on virtually every topic. You spend late nights just talking about different theoretical scenarios and brainstorming ideas. You fall deeply in love with his mind. He views football as a violent game of chess and loves to explain the strategy. He is a problem-solver and a self-described “fixer” who relishes the challenge of a seemingly unsolvable task. No one has ever been able to make you laugh as much as Bob. Your family and friends all love him – some even more than they love you. Every morning you pinch yourself.

He proposes six months later, and you are married exactly one year from that first date, just a few weeks after your 30th birthday.

Soon after your dream wedding, you make the decision to relocate from New York to St. Louis so Bob can get his MBA at Washington University. He has dedicated his career to “the greater good” serving to advance scientific discovery by supporting medical research scientists and has secured a position at Washington University Medical School supporting the Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology. It’s not long before you experience some traumatic trials – your dear brother has a freak accident resulting in a coma and head injury, and Bob’s father has some serious health issues including congestive heart failure at a very young age. The two of you face these challenges together and become even stronger as a couple because of these experiences. You are rock-solid.

You start a family.

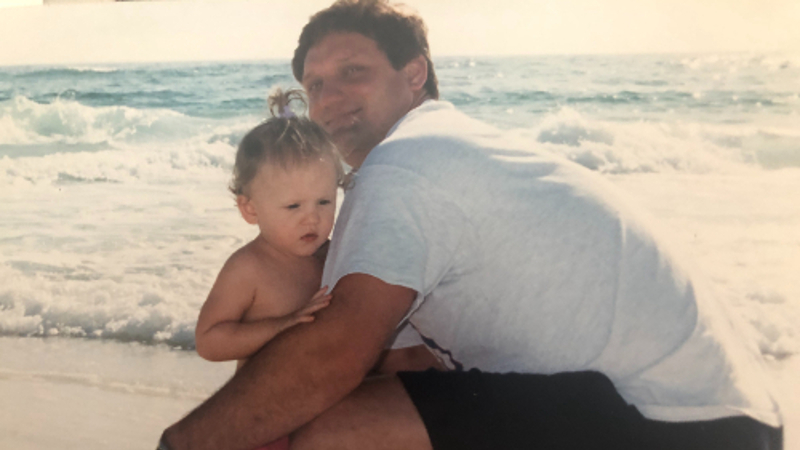

After being married for two years, you are blessed with a perfect baby girl who has the uncanny ability to increase your capacity for love in a way you never imagined. Sarah is the absolute center of your world, and life has never been better. Nearly two years later, your son Jack is born, and your family is complete.

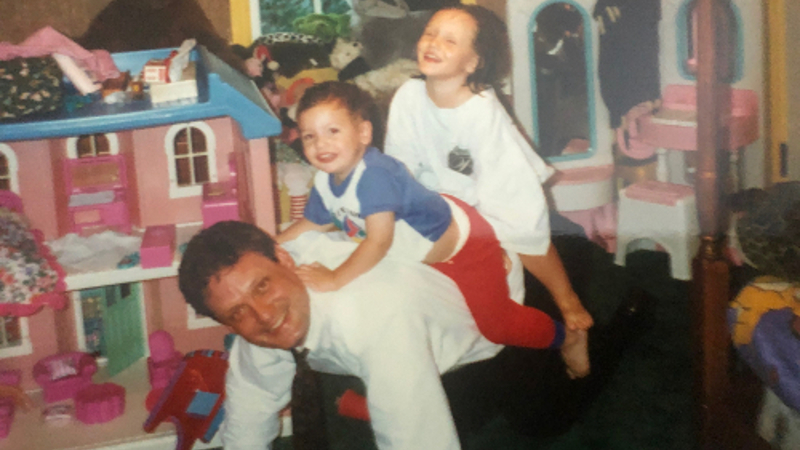

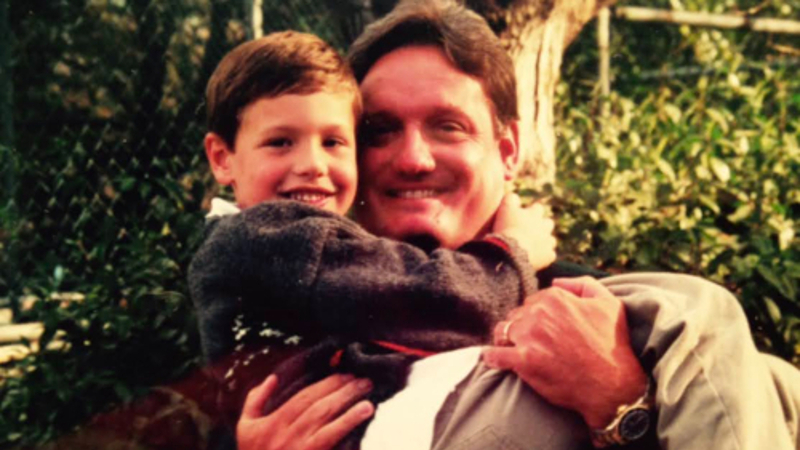

To say Bob is a great dad is a huge understatement. The kids are the center of his life, and he is a thoughtful and creative caregiver. He has “cowboy dinners” where he serves baby snakes (sliced hot dogs) and rattle snake eggs (beans) on tin plates (pie pans) outdoors. He takes the kids fishing and cooks up their “catch” (Mrs. Paul’s fish sticks). He gathers all the kids in the neighborhood to form an inclusive gang – and when they discover an elderly widow has a birthday alone, he has the gang throw her a party and a parade. I tell you all this because Bob Kurzu was so focused on others and creating meaningful, thoughtful, and purposeful experiences. He loves to surprise you with extravagant and romantic gestures.

Life is perfect…

You and Bob have amazing friends and an active social life. You love throwing parties and hosting game night. Fantasy football is a big focus of the fall and winter seasons, and often conversations will turn to Bob’s football days. Some of his funniest stories include the many times when he had concussions and did silly antics as a result – like the time he did a dance on the sidelines to prove to his coach he still had the moves to play, or when he introduced himself to his father because his bell was rung so badly, he did not recognize his own dad. Football is a big part of his identity and a point of pride for him and your family. The kids are huge Gator fans. You all go to St. Louis Rams games, and to two Super Bowls, and even watch the Gators win the National Championship.

Alcohol – especially beer – is always around and consumed quite a bit, but Bob is never drunk or out of control. Alcohol being a problem will never really cross your mind, even though you see the black Hefty trash bag full of empties after a weekend and know you did not drink any…

Around age 15, Sarah finds her athleticism and begins to excel at the sport of crew. She’s good. Really good. Recruiters take notice and it looks like she will be a D1 scholarship athlete. Jack is very big for his age and has loads of potential but is still developing. Eventually he will be a D1 football scholarship athlete, too. The three of them together conspire to create an exclusive “D1 Club” where you are not allowed to join. There is so much to be proud of. Life is so good…

…Until it isn’t.

So, knowing you, you are tapping your toes and getting impatient to learn what went wrong, especially if everything is so perfect.

It’s hard to pinpoint when the changes begin, but there are lots of little signals which in isolation seem so unimportant, but collectively your family life begins to unravel.

First, the drinking. It escalates with Bob to be almost constant. He allows you to drive so he can drink responsibly. He sleeps a lot. He even loses the job he loves due to drinking during the workday. This comes as a shock to you – but even more shocking is Bob’s insistence that he is doing nothing wrong. His behavior is normal in his mind – it’s the rest of us who have the problem.

Then comes the confusion. The man who once did regression analysis by hand to better his fantasy football odds now has trouble navigating simple websites or search engines. He gets lost while driving and misplaces items frequently.

Next, Bob’s writing and grammar degenerates. Always a point of pride, his language suddenly is noticeably peppered with double negatives, incomplete sentences, and typos.

His memory deteriorates and with it his ability to phrase grant projects for his work. To cope, Bob starts hoarding printed documents that he can turn to and copy from rather than draft new proposals. The solution is a chaotic system of massive stacks of papers in his study, reflective of a disordered mind.

His frustration leads to uncharacteristic and frequent outbursts of anger. He does not understand simple concepts – which makes Bob confused and paranoid. He will make wild accusations and even question your fidelity. He soothes his insecurity with alcohol.

He becomes surly and withdraws from his friends and his family. He uses work or exhaustion from work as an excuse to miss important events – the kid’s athletic competitions or their prom pictures. Soon, he can’t go anywhere without drinking. It’s a problem. A big one. And everyone is suffering.

So what do you do? You ignore it, hoping it will all go away.

How can the man who is the love of your life suddenly become unrecognizable? It’s incongruent with what you know the character and heart of Bob to be. He’s lying. He’s not taking responsibility. He’s mean. He says you are frigid and you are smothering the kids and not allowing them to grow up.

Bob is not the only one who is confused. Everyone is. His boss, co-workers, his children, close friends, and you. The most insidious thing? For the most part he appears to be normal to almost everyone but you and the kids. And then you discover he’s using you and the kids as excuses for his actions, blaming you all for his behaviors.

You feel so alone. There’s no one, really, who you can talk to who can empathize or understand this seismic shift in your husband and homelife. You’ve always been a private person, so even your closest friends don’t really know what you are dealing with. You become an expert on alcoholism and learn terms like “dry drunk” and “denial,” but something still doesn’t add up. This does not fit with the person whom you know your husband to be.

The breaking point.

Your daughter begs you to act. Her life has become intolerable as she is the one who calls Bob on his bad behavior. Your son is losing his confidence as Bob targets and compares Jack’s developing athleticism to his own former prowess. The once-happy home is now riddled with secrets and festering with the pressure to keep up appearances.

After many years of pleading with Bob to go to counseling, or to stop drinking, you finally draw the line when your daughter suffers from an eating disorder that threatens her life. Bob cannot or will not provide her with the support she needs. The verbal abuse escalates to him physically attacking you over the kids or your coldness towards him. You feel perplexed as to how you can be loving to this stranger.

Bob is now drinking a bottle of vodka or more a day. As a last resort, you take Bob to see a neuro specialist at Wash U Medical School who also happens to work with suspected Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) patients. Bob is tested, and the results are not conclusive. The good news? He does not have schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s. The bad news? He is decidedly an alcoholic. The worse news? You will not know if he has CTE unless his brain is donated to science posthumously.

On your birthday, you ask him to leave, and he does.

You’ve been married 23 years, and 20 have been perfect but the past three have been hell. Bob stopped working, and you are the sole wage-earner to support your family.

Bob will not go to rehab but attempts to stop drinking on his own. He sees visions – mostly angels and demons. He believes you are the devil and says he sees you have cloven hooves where your feet should be. He hears voices, and you become fearful for your safety, so you begin locking yourself in your room. One night, he bangs on your door to get in. You hear him walking away and then the lights in the entire house go off as he cuts the circuit breaker. You hear him whistling in the dark and walking back toward your room, hitting something in his hand which you later discover to be a hammer. Terrified, you call 9-1-1, and the police come. They confront him, and he agrees to leave. You cannot believe this is even happening. You pack his bags and tell him he needs to get help or you will divorce him. But either way, he can’t come back unless he changes.

Laura, I wish I could tell you this has a happy ending to match the fairy tale beginning. I’d love to tell you that was the end of the trauma and the violence, but it wasn’t. You suffer. Sarah suffers. Jack suffers. There is so much pain that cannot be taken away. But there is also tremendous growth, and your faith in God sustains you even during your darkest times.

After 25 years of marriage, you decide to divorce Bob. It’s the hardest decision you have ever made because he was and is the love of your life, and there is overwhelming guilt at breaking your vows… “for better or worse, in sickness and in health.” When this happens, please forgive yourself.

You try to help your children come to terms with the trauma of their childhood and you commit yourself to being there for them every step of the way. You pray for Bob and try to keep the door open but, when necessary, use all your strength to bolt it shut to protect your children from his toxic behavior. You see the hope in their eyes darken when he goes to rehab but checks out early or when he refuses to follow a program. He is no longer superman, and it’s hard to watch.

With death comes closure.

Arguably, Bob seems to have a death wish. His health declines due to his drinking, and despite warnings from his doctors, he will not or cannot stop. The man who held a seat at the table with the most brilliant minds in science now can’t hold down a job at the Dollar Store. He spends his last days confused and angry. He dies at the age of 59 in a small, low-rent apartment in his hometown where he once had been a football hero. The scumbags whom he lets into his life rob his apartment while his dead body is still on the bed, taking what little legacy he has left – his Florida Gator bowl rings and his Rolex watch.

You get the call from a dear friend who tells you the news – and are horrified at your reaction of relief that it’s over. This monster can no longer torment your children or you. And then the awful guilt sets in – what kind of monster does that make you? You are happy someone you adore has died such a lonely death?

And so, you go into full-on Momma Bear mode. You must steer yourself to tell your children that their father, whom they have been estranged from, whom they once idolized, whom they still hope to reconcile with, has left this earth. You feel their pain as if it’s your own, and you grieve both the lost years past and those years that will now never be.

You encourage your kids to mourn the loss by focusing on the man he was rather than the thing he had become. You travel to stand by their side and help wherever you can. You have relinquished your rights to be a grieving widow, although that is how you feel. When you attend the wake in the small town where he was a local legend, a huge surprise awaits. You are welcomed with open arms by long-lost friends and family. They show real love and empathy and desire to reconnect with you and your children to celebrate the Bob Kurzu we all loved so well.

Your heart swells with pride as your kids speak so eloquently at the funeral. They openly acknowledge the alcoholism but focus on the man they knew to be the real Bob Kurzu: the dad who made cowboy dinners. This opens the opportunity to have real dialogue about what his true friends had witnessed and the love he expressed to them about his kids – but also the confusion and addiction he struggled with. No more secrets.

You and the kids donate Bob’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank where it will be studied for CTE research. There is solace in knowing the man who had dedicated his life to advancing science would be once again helping scientific discovery with his donation.

Finally, something you can feel good about hating.

When you finally learn of Bob’s diagnosis, it’s as if the world shifts back into place and you are no longer in the upside-down. The cause of the inexplicable changes in his cognitive, physical, and emotional behavior now has a name – Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a progressive brain condition caused by repetitive head trauma.

While he most certainly was an alcoholic, it now makes sense that Bob’s drive to drink was to numb the pain and deal with the confusion caused by his progressively addled brain. The timeline of your life is now marked as “before CTE” or “after CTE” – and there is tremendous comfort in the realization that this was not something Bob could choose or control.

In the diagnosis review, the scientist tells you and the kids three things that are all incredibly helpful and equally heartbreaking:

- There was nothing any of you could do to prevent this.

- There was nothing any of you could do to stop this.

- There was nothing any of you could do to change this.

You focus on the memories of happier times and allow yourself to mourn the loss of the incredible man you loved so dearly – who was not the person who walked this earth over the past several years in a confused state of mind.

You allow yourself to remember details long forgotten, including a strange argument Bob and you had while on your honeymoon – where he says out of the blue, “You know if we had kids and it was ever a choice between saving the kids or you, I would save the kids, right?” Your response is something like, “Well, that makes zero sense because I am young and can have more kids, so the logical choice would be to save me.” (Remember, you have not had kids yet and have no maternal instincts).

What happens next is almost prophetic. Bob is adamant and makes you swear if you ever need to choose, you will save the kids versus him. You try to laugh it off, but he holds your shoulders, looks deeply into your eyes, and you make a vow.

And, years later when it comes time, you keep your word; you save the kids. Now you know in your heart without a doubt it’s what the man you loved would have insisted you do. You saved the kids from what CTE had made him. The kids know the story, and they both agree. You are all finally at peace.

xoxo

Epilogue

This personal essay was written as part of a research project. The intent of a “letter to their former self” is to use hindsight to reflect on the personal experience of what the loved ones of those who have CTE have experienced, and with this hindsight, what advice they’d give to their former self or to others who are going through a similar situation.

At the time of my husband’s change, information about CTE was very limited, and what information did exist was largely associated with those who played professional football. In my husband’s case, he only played at the collegiate level and most of his concussions we know about happened during high school, so it was not top of mind for CTE to be the culprit. We believed the only other diagnosis that made sense – he was an alcoholic.

I think the hardest thing for my journey was the confusion I experienced during my husband’s metamorphosis and descent. I could not reconcile the man that I knew so well with this person who was the exact opposite in nearly every aspect, including his core beliefs. I held onto the hope that he would change or eventually hit bottom and get help. But unlike alcoholism, with CTE there is currently no recovery.

The advice I would offer to families going through a similar situation is to gather as much information as you can about CTE – and then to be prepared to protect yourself and leave if you are in an unsafe situation.

I pray that donating my husband’s brain will help with the development of diagnostic tools that can enable families to achieve an accurate assessment of their own situation so that they can make the best plan for their loved ones.

If you feel you or someone you know is at risk of intimate partner violence, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) or text ‘START’ to 88788.

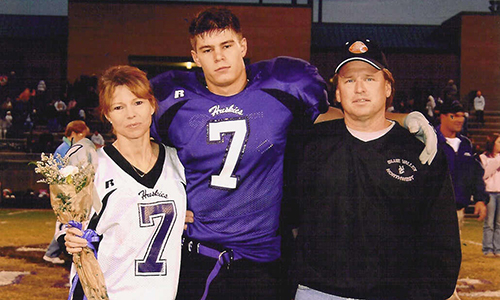

Zack Langston

Zack played football at a Division II school in rural Kansas at Pittsburg State University. Though on the smaller side for a university, Pitt State was well known for being the winningest D2 football team in history. Zack was expected by many to attend a much larger university and play Division I football because he possessed the speed, size and athleticism of a top college football player. He chose however to attend Pitt State, only two hours from home after deciding he would have more fun on a team at which he would feel like “a big fish in a small pond” as opposed to just the opposite at a larger university. In addition, he wanted to attend a school at which his family would be able to make the drive to most of his games.

Zack was very happy with his decision to play football at Pitt State as he made many great friends, had a fun college experience, met the mother of his child and thoroughly enjoyed his football career. He never expressed regret over not attending and playing football at a larger university.

Toward the end of his college career we noticed Zack was beginning to struggle with anxiety and become stressed over small things. His father and I attributed most of his stressors to be caused by thoughts of having to soon leave football behind, getting a real job, and becoming a responsible adult.

Over time, after graduating from college his stressors seemed to be caused by the smallest of things like losing his car keys or being late for an appointment. He would verbally beat himself up, at least to his father and me, telling us how incompetent he was and how he couldn’t remember things, like making plans with friends and things people had told him in conversation. He was worried and embarrassed thinking his friends saw him as stupid. He began to get upset easily and punch holes in walls or throw things. As angry as he would get though, he never took his frustrations out on a living being.

Zack was always very compassionate, caring and kind hearted and his kind reputation stayed with him until he died.

Zack lost interest in socializing with friends, which was very unusual because before, spending time with friends was very important to him. He became extremely paranoid, thinking his friends and acquaintances were saying negative things about him at all times. He didn’t trust anyone anymore.

Zack confided in me that he was uncomfortable socially with everyone, even his father and me. Though he had been a somewhat quiet person naturally, feeling this uncomfortable and awkward socially was not Zack at all.

Whenever he was not working, Zack seemed to do nothing but sleep. He had almost completely lost interest in working out, which we had a very hard time understanding because he had always been a workout fanatic. His extremely healthy eating habits became a thing of the past. He began to lose weight as a result because he sometimes didn’t care to eat at all. Always an extremely muscular boy, beginning from about 8th grade on up, his muscular physique began to deteriorate.

Zack informed us that he was taking Adderall on a regular basis hoping it would help his memory; we were never sure if it really helped.

Within the last several months of his life, he confided in his girlfriend, Morgan, and myself that he was having suicidal thoughts. He had met with several therapists, attempting to find one who understood and could help with his struggles. He eventually gave up on therapy, feeling that no one seemed to understand how to help him; they all wanted to prescribe antidepressants which he was totally against. He checked into a psychiatric hospital and even gave in to his strong oppositions of anti-depressant use.

We knew he was desperate to get better and, as his parents, we made sure we were always available to him, day and night. At the slightest hint of frustration in his voice, we would drop everything and go to him hoping to talk him through whatever seemed to be his problem; sometimes what seemed like a very small problem to us, was extremely upsetting to him.

I spent a tremendous amount of time doing research, trying to find answers after he told me that he felt that “football messed up his brain.” Zack had even asked Morgan that in the event that he did take his own life, that he would like an autopsy performed on his brain.

Zack had discussed with Morgan the details of how he was planning to take his life. He was going to shoot himself in the chest in order to preserve his brain so that an autopsy could be performed to determine any damage that might have been caused by football.

Over a period of three months, Zack had purchased three guns. We managed to confiscate the first two guns from him. His dad began tracking his phone; we began looking for excuses to call him at work just to make sure he was there; then he bought a third gun. We didn’t get to him in time this time. His death happened just as he had described to Morgan — a shot to the chest.

At the time of Zack’s death, his son Drake was just barely two years old. Zack and Drake had a very loving relationship and were the best of buddies. Drake was the most important thing in Zack’s life. I feel that deep down, even though Zack had talked about suicide, I somehow didn’t believe he would actually take his own life because of his love for Drake. Drake is now four years old and continues to ask questions about why his daddy died and if he will ever see him again. Our explanation to Drake is that “daddy played football and his helmet didn’t do a very good job protecting his brain, so his brain was broken.” This is the hardest part of it all.

To be able to have some kind of closure with the diagnosis of CTE, has helped to some extent and I will be forever grateful to Boston University for the work they have done to help us acquire this closure. However, as Zack’s mother I continue to feel cheated not having knowledge of this horrific disease before it was too late. In our son’s case, we had no knowledge whatsoever of CTE until eight months after Zack passed away. I only hope that the results acquired in the study of Zack’s brain will bring much needed knowledge in how to protect athletes in the future and hopefully save some lives as well.

We love you and miss you so very much Zack, but we know that you are at peace now.

You are forever in our hearts and our family will never be the same without you, but we know that you are looking down on us every day and that gives us reason to smile. I believe you were always meant to be one of Gods angels. We know you will do amazing work. You are forever our baby boy. Mom and Dad.

Click here to read the Vice Sports article on Zack Langston

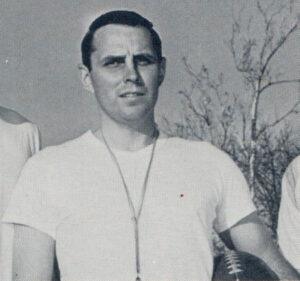

John Lantz

John Lantz, age 84, passed away peacefully in his sleep on Wednesday, July 28, 2021, in Orlando, Florida.

From his earliest days, John lived with energy, determination, and a love for the game of football. A 1955 graduate of Greenville High School in Darke County, Ohio, he earned the nickname “Bug” for his quick, darting moves on the field. As a senior, John helped lead the Green Wave to an undefeated season—an early sign of the leadership and resilience that would define his life.

John carried his passion for the sport to Taylor University in Indiana, where he played four years of college football before beginning a career dedicated not only to the game but to shaping the lives of young people. In 1961, John married his beloved wife, Jean, the very same week he began coaching at Versailles High School.

Though John’s first season ended with a 1-8-1 record, his perseverance and belief in his players transformed the program. Within six years, the Tigers were among the state’s best, winning more than 80 percent of their games under his leadership. In 1967, he was honored as Ohio’s Coach of the Year after leading Versailles to the state’s #1 Class A Division title.

Known affectionately as “Coach Lantz,” John then carried his passion and mentorship to Centerville High School, where he served as head football coach and career counselor, ultimately retiring after 21 years there. His guidance extended far beyond the field, helping countless students discover their strengths, pursue their goals, and believe in themselves.

John experienced severe cognitive decline and dementia during the last five years of his life. Before that, he showed no signs of depression, emotional instability, or related symptoms. After his death, his brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank and diagnosed with stage 4 CTE by researchers.

Yet throughout John’s life, he never wavered from the principles that defined him. He embraced and often shared a favorite saying that reflected his outlook on life: “A setback is simply a setup for a comeback to success.”

John’s story is one of grit, faith, and an unwavering commitment to others. His legacy endures not only in wins and titles, but in the lives he touched and the inspiration he gave to all who knew him.