Gus Lee

This article adheres to the Suicide Reporting Recommendations from the American Association of Suicidology.

Monday, December 10, 2018

Anxious and exhausted, Phyllis and Chris Lee decided to finally go to bed at their Vienna, Virginia home.

“If he’s going somewhere, he’s coming here,” Phyllis said. “He’s gonna come home.”

Gus Lee had finished his second football season at the University of Richmond and was set to take two finals that day. Finishing finals would mean he was one step closer to what was shaping up to be a fun and well-needed winter break. But texts and calls the previous day from Chris and Phyllis went unanswered.

Phyllis was worried after Gus’ roommate said he hadn’t seen Gus in a whole day. After a quick check with local friends and relatives, the family made the decision to involve the police in the search for Gus.

Jumping in

Augustus “Gus” Lee was the youngest of three and developed the kind of bravery that comes from watching older siblings. The Lees belonged to a neighborhood pool in Vienna. One day, neighborhood children took an interest in the daunting high dive. A five-year-old Gus was the first to go up, calmly, without saying a word.

Chris looked on in preparation for a last-second backout, but his son jumped off the diving board and into the pool. Gus blazed a trail and a cascade of other kids followed his lead.

Young Gus was a teacher’s favorite type of student and eventually a coach’s favorite type of player. He may not have been top of his class, but he listened with great intent.

The Lee family soaked up their time together before college splintered everyone’s availability. They hiked often and took many vacations to beaches along the east coast. The Lees were not the type to plant their chairs in the sand for hours on end. The beach was a recreation center. The family played football, kickball, racquet sports, and eventually started surfing.

For Gus, the beach was just another field to excel on. His amazing speed was on full display in whatever sport he picked up. Gus stood out from the time he was barely taller than the soccer ball he was kicking down the field.

The hits

Gus was knocked out cold in the middle of the field in an eighth-grade lacrosse game in 2013. Chris and Phyllis looked on while Gus’ coaches came to his side. Eventually, Gus sat up. He could answer who he was and where he was, but the score of the game he had just exited was a total mystery.

At the hospital, doctors determined Gus did not have a brain bleed. He was alert and talking. The best sign to Chris and Phyllis was that Gus was hungry, which meant the always-ravenous teenager felt like himself. ER doctors told the Lees to take him home, let him rest, and let them know if anything changed.

Two days later, Chris had a physical with the family doctor. Gus’ injury came up in conversation. The physician referred the family to a sports medicine specialist to assess Gus.

The specialist determined Gus was suffering from a concussion. No school, no sports, no activity until Gus recovered.

Gus returned to school about a week later and didn’t seem to have any lingering problems. But the specialist still decided sports were out of the picture. It took nearly six weeks for Gus to return to sports.

The delay shocked the Lees. He seemed fine. Gus said he was fine.

Gus would put football on pause after that season but kept playing lacrosse year-round. The concussion would be the only one Gus was ever diagnosed with, but he was involved in several high-impact collisions, including one during an indoor lacrosse game and another big hit in college.

At the time, Gus may have only had to miss a couple of plays or stay down for a few extra seconds on the turf. But Phyllis now believes some of those hits may have been undocumented concussions.

The odd couple

Gus transferred to Paul VI Catholic School in Fairfax, Virginia before his junior year of high school. Before the year, he started training with the Paul VI lacrosse players. Many of them also played football. Seeing his tremendous athleticism, they urged Gus to come out for the football team.

Initially, Gus declined. But Gus decided at the last minute he wanted to join the team in summer practice.

Gus became the perfect target for Paul VI quarterback Jimmy Check. Check could throw deep and Gus could go get it. Check, tall and lanky, and Gus, short and stocky, may have looked like a funny pair but the two boys were highly compatible. They were constantly practicing routes and perfecting their chemistry. Check to Lee became a combination worth watching.

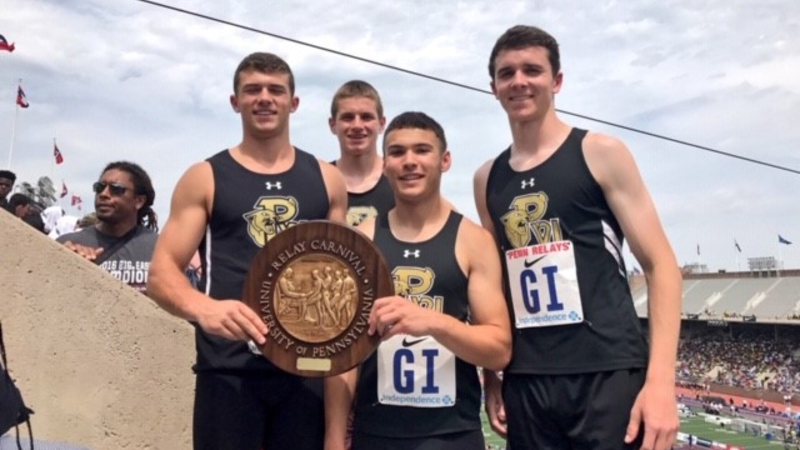

Gus’ senior season at Paul VI was one for the books. He was named captain, set the school record for receptions with 79, and made the VISAA Division I All-State First Team.

Gus checked a lot of boxes for your classic high school jock. He was handsome, athletic, and well-liked. Yet he lacked any of the undesirable qualities that come with the stereotype. He remained a diligent student. He was quiet. He was even a bit quirky. He also cared about every student at Paul VI, whether or not they had letterman’s jackets.

In need of an elective his senior year, Phyllis encouraged Gus to participate in Paul VI’s Options program. Part of the program connected Paul VI’s general education population with their special education students. Gus was a kid of few words, but his ability to listen made him a favorite among the Options students and faculty.

Richmond

Gus wanted to be a D1 athlete from an early age. His family thought it would be lacrosse that helped him achieve that goal. But the impressive stats from his senior football season garnered some last-minute attention from college scouts. He and his high school coach met almost daily discussing recruiting opportunities and finding a school that was a good fit academically and would afford Gus the opportunity to play and contribute to the success of the team.

Richmond fit the bill perfectly. Gus knew his family thought highly of the school already and after a day on campus with the coaching staff he happily accepted their offer to walk on to the football team.

Gus enjoyed his coursework at Richmond. He enjoyed the team workouts and thrived in the weight room. He did not particularly enjoy redshirting and having to watch the game from the sidelines. He had been recruited as a slot receiver but the coaches switched him to defensive back. He worked hard to learn the new position and adjusted quite well.

He liked meeting new people. He liked going to parties. But all the newness wasn’t enough to drown out how much he missed what he had grown comfortable with at home. He missed his high school friends. He missed his bed. He missed the family dog, Beanie.

By that point, Gus was Phyllis’ third child to go through the college adjustment process. This homesickness didn’t seem like anything out of the ordinary.

In the annual Spring Game on April 21, 2018, Chris and Phyllis finally saw Gus dressed in full pads for the Spiders. He intercepted a pass, recorded seven tackles, and was named the game’s defensive MVP.

Gus was back home a few weeks later but didn’t have much time to recharge. He got a summer job digging wells. Gus worked long, hard hours in the hot Virginia summer and returned at night covered in earth. Well pumping took Gus into late June before he got time to spend a few days with friends at the beach in Wildwood, New Jersey and a few more at the Outer Banks. Then it was back to Richmond for a summer class and the start of summer workouts.

The 2018 season opening game was nerve wracking for the entire Lee family. Chris and Phyllis didn’t know what to expect. Would Gus even see any playing time? But they happily drove to UVA in Charlottesville where Gus’ older sister Gillian had already graduated and his brother Jackson was in his fourth year.

The family all watched Gus play on the kickoff and kick return teams. He made several appearances on the Scott Stadium video board. The Spiders did not win that night but Gus made sure to find his parents after the game for a hug and a quick check-in before boarding the team bus, a ritual they repeated each game for the rest of the season.

“I’ll be home in an hour.”

Gus got sick with bronchitis during the season and came home to Vienna to rest. After he recovered and was back on campus, Gus and Phyllis began speaking often on the phone.

These calls elucidated how Gus was again struggling being away from home. Gus, who was usually to food as a Dyson vacuum is to dirt, had little appetite and was worried about losing weight.

The Spiders’ season ended on November 17, 2018 with a hard-fought win at William & Mary. Stressful finals loomed for Gus, but so too did the comfort and relaxation of the holidays. Gus had started making winter break plans that included a visit to a game at FedExField with his friend Danny.

On Wednesday, November 28, 2018, Gus called home. He was lonely and homesick, he said. He was already halfway up to Vienna from Richmond. He’d be home in an hour.

Gus didn’t seem overly emotional when he arrived. Chris and Phyllis asked if got into a fight or was in trouble with his team. Gus said there was nothing wrong – he just wanted to come home. He missed his friends and family.

Sensing signs of depression, Phyllis asked Gus if he would be receptive to therapy to help him out of his funk. He obliged.

Phyllis made dozens of phone calls to try and find Gus an appointment. Most therapists’ earliest availability was in two weeks. Not soon enough. Finally, a friend’s recommendation came through. A therapist agreed to see Gus after her last patient on Thursday, November 29.

The therapist told Phyllis how Gus had characteristically done more listening than talking but agreed to continue speaking with her over the phone while he was at Richmond. Phyllis mentioned how Gus was a long-time contact sports athlete with a potential concussion history. The therapist recommended Gus should see a psychiatrist for a full screening. They scheduled the screening for Gus’ return to Vienna over winter break.

“You must be so proud of yourself.”

Gus returned to Richmond ahead of finals. Phyllis and Gus kept up their calls.

Meanwhile, Phyllis connected with Shannon St. Pierre. The friendly compliance officer became Phyllis’ eyes on the ground for Gus’ status on campus. Phyllis spoke with St. Pierre often, and asked at one point if Gus was doing well.

St. Pierre seemed surprised at the question. She saw Gus often studying with friends, appearing in good spirits. He even popped by her office to give an update on how his older sister was doing and his plans for winter break.

A call from Gus corroborated St. Pierre’s account. He told Phyllis he got a 92 on his calculus final.

Phyllis used a parenting verbiage trick to bolster Gus’ confidence.

“You must be so proud of yourself,” she told him. “People hate math!”

She was proud of him, of course. But she felt Gus needed to feel the esteem, too.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Gus was still missing. The Lees decided to go to Richmond to try and find their son. As they were about to head out, a Virginia state policeman arrived at the door and told them the devastating news. Gus was gone. He had died by suicide two nights earlier. A snowstorm in Richmond covered Gus’ car and hid it from police on their first search.

Pretending

Chris and Phyllis drove to Richmond and arrived to receive an outpouring of support from the school community. St. Pierre helped the family collect Gus’ things and meet with Gus’ coaches and the school’s chaplain.

Phyllis worried Gus’ suicide was an indicator he didn’t have many friends at Richmond. But the school gave the family a box stuffed with handwritten notes from students who knew Gus, filled with stories of how Gus made them laugh, inspired them, or had been there for them in their time of need.

The Lee family was left to wonder why Gus didn’t feel he could ask the same of his friends.

“From the outside, he seemed like he had a perfect life,” Phyllis said. “He was pretending to everybody that everything was fine.”

Searching for answers

In her sleepless nights after Gus’ death, Phyllis decided she wanted to donate Gus’ brain to the UNITE Brain Bank.

Phyllis initially donated Gus’ brain with the thought he may have had Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease caused by repetitive head impacts found in the brains of hundreds of former football players. But the more she researched the disease, the more she questioned whether Gus’ symptoms fit.

Before his death, Gus wasn’t struggling cognitively or behaviorally. He maintained good grades, had a flawless memory, and was thriving socially. Phyllis wasn’t surprised, then, at the pathology report from the Brain Bank. Dr. Russ Huber found Gus did not have CTE.

Dr. Huber’s detailed report concluded Gus’ brain exhibited many of the molecular and structural changes that precede the onset of CTE in the brain and are consistent with a history of brain trauma.

In the report, Dr. Huber wrote: It is a case that could easily have had CTE but doesn’t. I would hope that this case will be part of the resilient group that we are studying to find out what kind of genetic factors and lifestyle choices are important to prevent CTE.

Starting the conversation

While Gus’ brain was being studied, the sports community rallied around his death. Teams from across the country sent autographed footballs and jerseys to the Lees.

A.J. Mejia played football with Gus at Paul VI and went on to kick for the University of Virginia. Mejia changed his uniform number at the University of Virginia to Gus’ Richmond number 28 for the 2018 Belk Bowl. Virginia won the game 28-0.

Roman Puglise played lacrosse with Gus at Paul VI and went on to play for the University of Maryland. When Maryland played Richmond on February 9, 2019, Puglise changed his number from 8 to 23. Gus wore 23 for the Paul VI lacrosse team.

The gifts and number switches started important conversations in college locker rooms about mental health. Through tears, Puglise spoke to his Maryland teammates about the prevalence of mental illness and reinforced that it was OK for an athlete to speak up about their own mental health.

Since Gus’ suicide, the University of Richmond hired a psychologist for the athletic department.

Phyllis came to learn about the intersection of concussions and mental health. A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found the rate of suicide is twice as high for individuals who have experienced a traumatic brain injury.

“I knew that concussion was a serious issue and needed attention,” Phyllis said. “But I didn’t know that there were these other long-term dangers. And parents need to know that.”

Parents can help their children, but Phyllis and Chris want athletes to know how to help themselves. They believe athletes should tend to their mental health status as seriously as they would a sprained ankle. Gus had plenty of friends, teammates, coaches, and family that he could have confided in.

“Athletes need to know that if you play a contact sport, you’re at a higher risk for crisis,” Phyllis said. “They need to recognize how they’re feeling and then be open and honest about those feelings with others. It’s heartbreaking because we would have moved mountains and spent our last dime to get him the help he needed had we known he was in distress to this level.”

Suicide is a complex public health issue, involving many different factors. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide most often occurs when stressors exceed current coping abilities of someone suffering from a mental health condition.

The Lee family still holds the sports Gus played in high regard. Sports were central to Gus’ identity and provided him with tremendous opportunity in life. It’s their hope the millions of contact sport athletes who may be struggling know they’re not alone and that it’s OK to not be OK. They hope their honesty and sharing Gus’ story will save lives.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

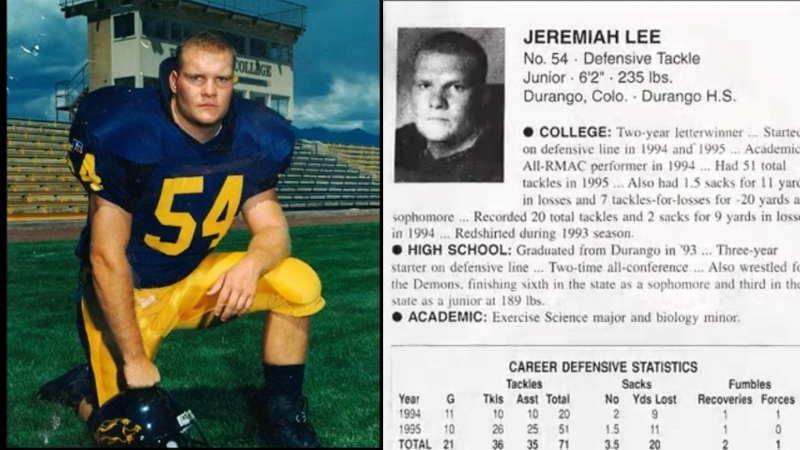

Jeremiah G. Lee

“J LEE”

Our family is very grateful and honored to have the opportunity to share the life of Jeremiah Lee as a donor to the UNITE Brain Bank.

The extraordinary thing about death is that it honors one’s life. In life, Jeremiah believed he had no honor. In death just the opposite is true. We’d like to think, that had Jeremiah known or believed the truth, he would not have done what he did, or at least would not have been so hard on himself. Jeremiah left this earth way too soon, as he felt his life was no longer worth living. He somberly thought he had let down every person that he loved. He was embarrassed by his actions, by his dependency on alcohol, and for the way his life had evolved; for he knew his life originally had great promise and purpose.

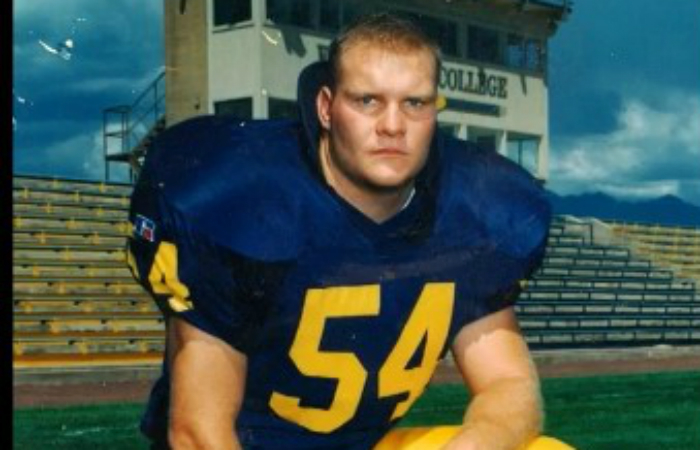

We were the typical “sports family” taking in football, wrestling, and baseball; in between sports we shared hunting, fishing, horse riding, and raising cattle. Jeremiah loved sports, especially football and wrestling, and because of his love he excelled as an athlete.

Karl Mecklenburg of the Denver Broncos was his role model, but his one true paradigm was his father; Wayne Lee, played Defensive Tackle in high school and at the University of Northern Colorado. In 1960, Wayne was drafted by the Denver Broncos as a Guard. Jeremiah took in all of the knowledge, instruction, and coaching his father had to offer and was a natural from day one. Even though Jeremiah wasn’t big in stature he followed in his father’s footsteps and played Defensive Tackle. Jeremiah played football wholeheartedly through middle school, high school, and earned a football scholarship to Ft. Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. During his senior year at Ft. Lewis he coached the line of his college team. He was a natural team leader on the field and on the mat. He was very well respected by his teammates, as well as players from the opposing teams. He took the hard hits on the line, and he hit back twice as hard. He never ever quit; he would take the hard hits that “rung his bell”, and would get right up, continue on with the game, and push through his pain. His football buddies said, “Jeremiah hit so hard that no one wanted to go up against him for they knew they were going to get hit, and hit hard!” His friends endearingly called him “J Lee”.

Jeremiah graduated from Ft. Lewis College in 1998 with a bachelor’s degree. In between his Junior and Senior years at Ft. Lewis, Jeremiah attended Trinidad College to get his training and certification in Law Enforcement. Upon graduating the police academy, he was hired by the City of Durango Police Department and served 18 years on the city force. He then moved on as a deputy for the La Plata County Sheriff’s Department. During this time he served as a School Resource Officer, obtained the rank of Sargent, married and had 3 children, coached middle school football for several of the years, and became the “sports and 4-H dad”; he deeply and dearly loved his children. Jeremiah received several honors as Officer of the Year, and just months before he died Jeremiah was honored by the Colorado Cattleman’s Association as Officer of the Year for the Sheriff’s Department.

As a child and young adult, Jeremiah loved life. He loved to cook, and created his own recipes. He was an avid hunter and fisher, also taught by his father, and was extremely passionate about the great outdoors. Although he was a true man’s man, he was a gentle giant. He never passed up an opportunity to share his love of nature with his comrades, and although his life was busy and hectic he was always very dedicated and committed to his friendships; he never let anybody go by the wayside, not even his elementary and high school friends. Jeremiah also never passed up an opportunity to go out of his way to lend a helping hand whether it be a stranger, a family member, or a friend.

The truth is, all whom encountered Jeremiah loved and respected him. Jeremiah knew no stranger; he strived to, and more often than not made friends with each and every person he acquainted. He was well known, respected, and loved by his entire community. In the “good cop, bad cop scenario”, Jeremiah was the “good cop”. He always gave everyone the benefit of the doubt, and in a crisis/emergency situation he readily put all others before himself, and literally gave the shirt off his back. He was not trying to be a hero; he never thought of himself as such, it just came natural to him. 8 months prior to his death he was in a head on collision; and although he sustained very serious injuries and yet another head trauma his concern was not for himself, but for the other driver. He readily went into “football mode”, and managed to squeeze himself out of his badly crumpled squad car in order to rescue the driver that had swerved into his lane. Her family deemed him a hero on that snowy day, and publicly recognized Jeremiah as her “guardian angel”.

Despite all the respect Jeremiah earned from sports and his community, his most defining moment seemed to be the overwhelming life changes he faced all at once; the loss his father, losing his job with the city, and a divorce. He felt like a complete failure and his dependency on alcohol became increasingly prevalent. He seemed to be scatter brained; going from one task to the next, never completing anything. He undoubtedly had lost his love for life. All of us close to Jeremiah witnessed the most drastic change in his last few months; an escalating change, spiraling all too quickly out of control. Suffering from depression and PTSD; his memory failing, his paranoia and anxiety palpable, his hallucinations became his reality. Outbursts of impulsiveness and anger caused great distress, and Jeremiah seemed to no longer distinguish reality from truth. The changes were so significant that the question of CTE was raised by his closest college football buddies.

Jeremiah; our beloved son, brother, father, uncle, and friend left this earth on October 13, 2017; one day before his 43rd birthday. The outpour by his community was most incredible. One of the most profound events ever witnessed in the small town of Durango was Jeremiah’s memorial service. Two massive fire engines; ladders towering into the sky and toward one another suspended, in all enormous glory, the pride of our nation’s flag. Down below; in full dress uniform, all branches of first responders stood at attention with heads solemnly bowed, silent with upmost reverence. They lined both sides of the long path that lead his family into the gymnasium of the college where Jeremiah had graduated 19 years before. Friends, and family packed the stadium to give due honor and tribute to his life.

Jeremiah Lee was a very proud, yet humble man. He never recognized the impact he had made on his community; nor was he aware of how much he was loved or how much he would be missed. We would give anything to have him back, if even for just a moment to convey to him the monumental impact he so freely bestowed on so many. Jeremiah was undoubtedly an asset to his family, to his friends, and to his community. He will never be forgotten, and will forever and most honorably be remembered not for who he was when he died, but for whom he was when he lived.

The fact that we share Jeremiah’s life is to help raise awareness of the seriousness of repeated hard hits and concussions. Thank you to all research team members of Boston University. Your professionalism, compassion, understanding, sensitivity, and organization are most deeply appreciated.

Philippians 4:8

Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right,

whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable,

if anything is excellent or praiseworthy, think about such things.

Terry Lewis

Meiko Locksley

Michael Lopez

Michael Louis

Gerald Luchau

Rob Lytle

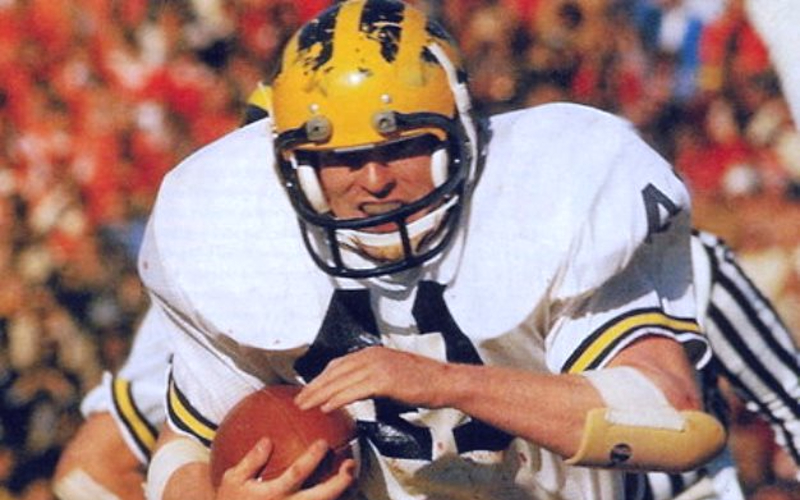

Adding 11 + 20 + 10 gives you 41. My husband, Rob Lytle, wore number 41 on the football field for the Fremont Ross Little Giants, Michigan Wolverines, and Denver Broncos. He wore it in the Rose Bowl and the Super Bowl. Rob died on November 20, 2010. How heartbreaking that he would die on this day.

The events of that day weigh on my heart. Our daughter, Erin, and I were shopping in Columbus. I had left Fremont—the small Ohio town where Rob and I lived—in the morning before Rob was awake. Never a morning person, lately rising from bed and starting a new day had become almost more than he could bear. While leaving town, though, I realized I had forgotten something. At home, I caught Rob freshly awake and struggling to walk down the stairs. As he descended the stairs, I watched his knees refuse to bend. He leaned against the railing, which strained and wobbled loose from the wall, failing against the weight of supporting my suffering husband. Rob grimaced. His many years of football had devastated his body. My heart winced.

Knee operations in the teens had led to an artificial left knee and multiple shoulder surgeries had led to an artificial right shoulder. Rob had mangled fingers that pointed in all different directions. He suffered from vertigo, incessant migraines, and eighteen months earlier had survived a stroke. In recent months, his mood had soured and his spirit seemed beaten. He was distant and depressed—forgetful and lost in our conversations—a cloudy shade of the man I had loved for forty years.

Standing together in the kitchen, Rob prepared to devour a breakfast quiche of eggs, cheese, and sausage. I fussed with a Christmas setting on the table. Just the night before we had carried eight loads of Christmas decorations down three flights of stairs while carols sang on the radio in the background. I kissed Rob goodbye before his first bite, not realizing that this would be my last contact with him.

Every moment in life is precious.

While shopping, Erin and I got the call that Rob had had a heart attack. Life flashed before me. I saw our first kiss and first dance, our last fight and last hug. Was Rob alive? The doctors wouldn’t share anything over the phone. I prayed, wept, and hoped as Erin drove us two hours north from Columbus to Fremont.

Once at the hospital, Erin and I were joined by Kelly (Rob and I’s son). A young doctor ushered us into a conference room. I will never forget the sight of my children falling to the floor in anguish as we heard the news. Our Rob—my Rob—had died. They had just lost their hero, and I had just lost my husband.

The next day, the Concussion Legacy Foundation, then the Sports Legacy Institute, called and asked if we would donate Rob’s brain for their research on head trauma. I had never heard of them or the cause before the call. Rob played in an era when a concussion meant only that you had had your bell rung and where the first fix for an injury was to rub some dirt on it while the second was a series of painkilling injections.

Still, Rob had mentioned many times in conversation that he suffered at least twenty-four concussions that he remembered during his career. One stood out, and I can remember us laughing about it. In 1978, during the AFC Championship game versus the Oakland Raiders, Rob had smashed into Jack Tatum near the end zone and fumbled. Except the referees disagreed and ruled that Rob was down before he lost the ball. Oakland coach John Madden fumed it was a fumble and sprinted along the sidelines screaming at officials. Denver scored a touchdown on the next play, won the AFC title, and played in Super Bowl XII.

In our talks, Rob had told me he didn’t know what happened on the play because he had been “out cold.” He also admitted that he remembered little of the AFC Championship because of the concussion he suffered versus Pittsburgh one week earlier. “I had to play, Tracy,” I can remember Rob saying.

Never did I think that all these concussions could have caused Rob’s changing personality. Rob and I recognized how football had abused him physically and emotionally. What we never realized was the mental destruction the game caused. After the Foundation studied his brain, doctors diagnosed Rob with moderate-to-severe CTE. They told us it was a “miracle” that Rob held a job and functioned in society given the advanced state of his brain’s decay. They were shocked he had been able to mask his suffering. Rob’s somber mood, mental fumbles, issues remembering dates, and recent withdrawn personality came into sharper focus. Before this moment, we had not realized the connection between these problems and football.

Rob’s years of repetitive, violent collisions on the football field had caused CTE. And CTE had caused the change in my best friend of forty years.

Rob was a Fremont Ross Little Giant both on the track and football field where he dreamed as a little boy of becoming a professional football player. We had known each other since 7th grade, but it was while running track our junior year of high school that our lives intertwined. I was captain of the girls’ team, and Rob was the star for the men. During practice one afternoon, the girls were short a starting block and needed to borrow one from Rob. Easy enough. Except everyone was afraid to approach him. He was the star, the fastest on the team, and his sometimes-brash mouth plus the “don’t mess with me” scowl he wore when competing intimidated most.

Not me. When I asked if we could use his starting block, a smile spread on his face and his eyes softened. “Of course,” he replied, and our friendship began.

We dated through high school, spending nearly all our time together. Rob gained over 2,500 rushing yards for Fremont, and in 1972 the Ohio United Press International and Associated Press voted him all state. Coaches from colleges across the country sought Rob’s services. They even knew to call my parents’ house when they needed to find him.

I remember winter nights when the two of us would be outside laughing while digging tunnels or building forts in the snow outside my house. The phone would ring inside as recruiters called to make their pitches, and my mom would holler at us from the window. “Tell them to call back,” Rob would say and laugh. I suppose I could have known then that for him family would always come first.

Rob narrowed his college choice to Ohio State and Michigan—Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler. Woody would visit Fremont and sit with Rob for hours talking Civil War history and military strategy, favorite subjects for each. He told Rob that he could play as a freshman. Bo said simply: “You’ll never be as great as you are right now. We have six halfbacks already at Michigan. If you come here, you’ll be number seven. Anything that happens after that is up to you.” Instantly, a father-son relationship developed between Rob and Bo.

Rob and I attended Michigan together. When I moved in, several older girls laughed when I told them that my boyfriend played football. “Won’t be your boyfriend for long,” they scoffed. “Good luck,” they mocked. I guess we proved them wrong.

While at Michigan, Rob was a member of three Big Ten championship teams. He ran for 3,317 yards and scored 26 touchdowns. Rob currently ranks 8th in rushing yards in school history and 11th in all-purpose yards with 3,615 on 579 touches. As a senior in 1976, Rob ran for 1,469 yards, was named first team All-American, and the Big Ten’s Most Valuable Player. He finished third in that season’s Heisman Trophy balloting behind Pittsburgh’s Tony Dorsett and Southern California’s Ricky Bell. In 2015, the National Football Foundation inducted Rob into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Before his senior, All-American season, Bo asked Rob if he would play both fullback and tailback—requiring him to sacrifice carries, yards, and a shot at the Heisman Trophy—so they could maximize their talent on the field. Rob made the switch willingly. Michigan led the nation in total offense and won the Big 10 championship that season. Bo always preached, “The team, the team, the team.” Later, Bo would state many times that he felt Rob was the best teammate and toughest player he ever coached—perhaps the greatest praise Rob received for playing football.

Humility, self-sacrifice, and putting teammates above himself mattered to Rob. He loved football and lived to play the game.

We married on June 3, 1977, in Fremont. Since Rob was drafted in the second round by the Denver Broncos, we moved to Denver to begin our lives. Rob was fortunate to spend all 7 years of his professional career with Denver. As a rookie, he scored a touchdown in Super Bowl XII. Even though Denver lost to Dallas, it was an exciting moment in our lives.

While a Bronco, Rob worked at Cotrell’s Clothing Store in the offseason and involved himself in many charities. He served as honorary chairperson for the Listen Foundation, worked with the United Way, and helped with the Special Olympics. He was a fixture at fundraisers during those years.

Injuries filled Rob’s professional career, and it seemed we lived in operating rooms and hospitals. He always worked to overcome them, though, and return to the game he loved. Still, the body—and mind—can only bounce back so many times before it screams no more. In 1984, Rob’s final knee operation was more than his body could conquer. While playing for Denver, Rob scored 14 career touchdowns and ran for 1,451 yards to go along with 562 receiving yards. He reached the pinnacle of his profession, but left regretting that injuries kept him from ever playing to the level that he knew he could reach.

We returned to Fremont in 1984, where Rob worked in his family’s 5th generation men’s clothing store. Retirement was difficult for Rob. Though his heart longed to continue playing, his body could no longer take the physical toll of football. On many nights in the first years after leaving football, we would retreat to the couch after Erin and Kelly had fallen asleep and Rob would sob as I held him. He missed football, but even more he missed the purpose and direction the sport gave him. He believed that he had failed, despite playing seven seasons in the NFL, because he never achieved the impossible goals he had for himself. Over time, we put the pieces together, but Rob’s longing for the game never faded.

Rob closed his family’s store in 1989, and then worked for Bowlus Trucking and Turner Construction. Rob later became involved in the banking business and was vice president and business development officer for a regional bank in Northwest Ohio when he died.

During these years, Rob was a wonderful father and friend. We spent every Sunday with Erin, Kelly, and friends in some pick-up game of softball or football. The lasting memory of Rob for so many people is seeing him with a big smile on his face, surrounded by laughter, and immersed fully in a game or activity with his kids.

Once again, Rob became involved in the community. He was a Rotary president, YMCA board member, and assistant football coach. He served on the board of his favorite organization, the Sandusky County Board of Developmental Disabilities, and they even named their new facility after him because of all the support he gave.

Rob was blessed with a kind and genuine spirit. He invested himself in helping others, and lived his life filled with passion. Rob always wanted to make a difference in people’s lives while striving to include them and put a smile on their faces, which he could almost always do thanks to his sense of humor. Rob believed that every person was important and had a story to tell. He taught our children to be kind, considerate, compassionate, and to care for others. Rob filled our children’s hearts and minds with pleasant memories of meaningful times spent together.

We remember Rob as a loving father who shared the fun and pain of raising a family. Rob always listened, loved, and helped. More than anything else, he loved his family.

Rob wasn’t perfect, but he tried with everything he had.