Kurt Schmitz

Our whole life revolved around sports. We had a sport for every season, starting with soccer, then in later years football, wrestling, and baseball. My daughter was in volleyball, basketball, softball and dance. We played every venue in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, California and Alabama. Family life centered around sports, and our family shared wonderful times at practices, games, and recitals. I never imagined that sports would be responsible for my worst nightmare – life without one of my children. I want to share my story with you in the hopes that it will bring awareness and maybe help other families who have lost young ones. I will speak through my son’s own words as written in his many texts to me, as seen in italics. It is not my pain that I want to show you, but rather my son Kurt’s.

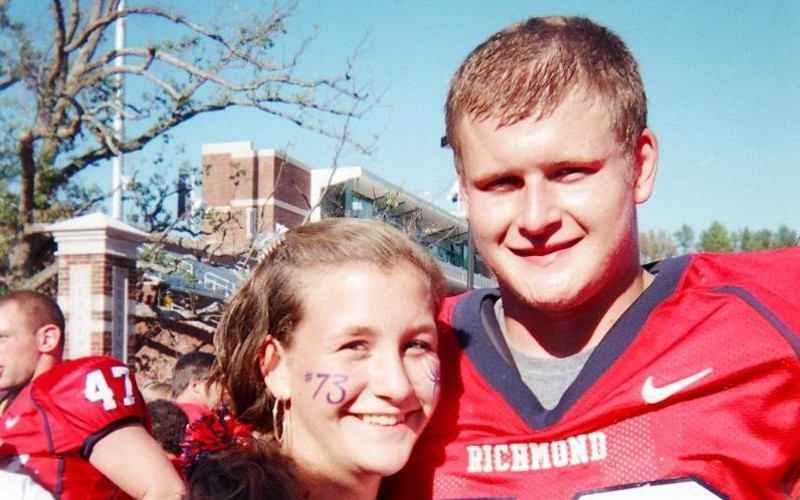

Growing up in New Jersey, Kurt saw the football stadium at Don Bosco High School and there was no turning back. He looked me right in the eyes and said, “This is where I want to go to school.” The 7AM to 10PM day included grueling hours of double session training. His junior year, he broke his leg in three places and missed the entire season. But senior year he worked twice as hard and earned his spot at left tackle on the varsity football team. That season marked Bosco’s sixth straight state championship and played a team from Alabama to win the National Championship. Kurt’s outstanding play earned him four full scholarship offers, finally accepting the University of Richmond, never losing sight of a dream to play professional football one day.

Kurt experienced leg and ankle injuries that sidelined his play. Determined to get healthy, Kurt rehabbed steadily through the winter until spring training. Then in August of his freshman year, he sustained his first concussion. Kurt was so eager to play that he lied to his coaches and started five games as a freshman without ever giving the concussion its proper rest. “Whatever, I’ll get healthy this year and punish next year.” His normal process of rehab to get through the next season started once more after his freshman year.

The next year he moved to center and thrived at his new position. “Good to go.”

At a practice the following August, Kurt took a hit which forced him to go to the hospital. When asked where he was, he responded, “Out on the field for a fun day having fun.”

Kurt loved the sport deeply, but it was not kind to him. The text messages began around this time and they were heartbreaking: “I just hate sitting in my room when all my friends are doing things I can’t do. And I don’t know anymore – Dr. White obviously thinks it’s migraines but I don’t know. I never friggen had a migraine in my life and this sh*t only started after last semester. Can’t get through one class without a headache.”

My son’s “invisible” injuries were compounding and his health was in decline. Kurt was given a medical redshirt, but this time there was no rehab. His headaches sidelined him from football and made it impossible for him to perform in school as well.

After an attempted workout over Christmas break, he called me and was frantic. His head was spinning, he was vomiting, his left arm had gone numb, and he was having difficulty swallowing. He tried so hard to fight through it, but enough was enough. In February 2012, I brought Kurt home to be evaluated by a neurologist in New York. He agreed to the visit and quit football before any further damage was done.

Kurt was devastated and decided to take a leave from school for the rest of the semester to try to get healthy. We tried several avenues to get answers for what was happening to Kurt, one being a psychiatrist.

“I’m gonna start seeing the psychiatrist again. I’m convinced I’m different from these concussions. That’s what upsets me. I know I just feel I’m different and I hate not being able to control it. Love you.”

No matter what Kurt was feeling, he always ended his text messages with “Love you.”

We thought he recuperated well enough to return to Richmond and finish his last two years. However, instead of bouncing back, his decline rapidly continued, and we ached for him and the emotional pain he was in.

“I can’t believe how much my life is just different in one year. I want to crawl into a hole and never come out to see the time of day. I changed. I’m different and I just ruined the best thing to ever happen to me. I can’t play football anymore and I’m just so depressed idk what to do. I honestly give up.”

“I’m just scared I kinda am messed up from my concussions like ever since freshman year when I got the first bad one. My emotions in general and thoughts have been just so different, and I tell you I’m good and great cause I am compared to where I was, but I truthfully don’t know if I’ll ever be the “same” me I guess you could say. Mom I was in a bad place after that 4th concussion diagnosed and God knows how many I got at Bosco on top of them. I don’t think I’d actually get any better. And that’s why it kills me cause the thing I love something that was seriously a part of me has ended and negatively affected my health and there was nothing I could do about it therapy wise. I honestly step back after saying something and I cry cause I can’t believe what I just said or thought and it destroys me cause I just never never was like this. I’m sorry for being so bad and immature. I promise I’m getting help as soon as the doctors get on campus. Good night – I love you. I never meant to be a bad person.”

Kurt passed away on November 30th, 2014 from a heart condition caused by high blood pressure. I made sure that his brain was studied at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston. There, researchers did not find chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), but they did find possible signs of trauma. To me, football unquestionably impacted how Kurt’s final years played out.

Do you know what it feels like to be a mom and receive these messages of despair? The texts left my husband and I unspeakably and unthinkably devastated. As parents, we feel the need to guide, nurture, and protect our children. But we were helpless in this situation, unable to heal our son. Parents are meant to help their children, and I felt unending guilt for not intervening earlier and stopping him from playing football. I kept thinking, “What if I had only known?”

I am telling my son’s story to all the parents out there who need to know and understand how life-threatening concussions can be. Had I known, I would have been able to guide my son better or would have helped him understand that what he was feeling was not from immaturity or being a bad teammate or worse yet, from the ADD he was incorrectly diagnosed with during this process.

Kurt was the salutatorian of his 8th grade class. He graduated high school with a 98.2 grade average and was a mathematical wizard. All those characteristics disappeared because of the many hits he took on the field. At that time, neither I, nor the physicians who treated Kurt, were fully aware of the full repercussions of concussions, and how each one needs to be treated with the utmost care. I hope that this story can create that awareness that we never had.

I read that NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell insists that football is safe, and that “there’s risk in life.” However, I wonder if he would feel the same way if his daughters sent him messages like the ones Kurt sent me. The work and dedication of the Concussion Legacy Foundation informs us that “pushing through” concussions could bring about serious complications, even death, from brain trauma. How can we deny the findings that Dr. Ann McKee brings forth with each brain she examines? We cannot continue to believe that a devastating brain injury can only happen to our children if they go pro. Have you ever viewed the donors page website and seen the ages of the Legacy Donors? Look and see how many there are that never played at NFL level. My son never had the chance to graduate college. He passed at the age of 22 and suffered for three years prior to his death.

I shared my son’s text messages because they reveal the excruciating emotional and physical pain he was in. He loved the brotherhood bonds he created with teammates in every sport he played. But, given the choice between death and leaving a sport before the damage was too far gone and destroying his life, I know what his choice would have been. Kurt loved life too much and his family even more. Had he known what this led to, he would have walked away after the first bad concussion and enjoyed everything else he had worked so hard to achieve.

I am in favor of sports — they were integral to our family and we loved those shared experiences. My plea is to increase concussion education and awareness. Concussions happen in sports, and every family at every level needs to understand the dangers and treatment protocols. The excitement of competition pales in comparison to the pain of losing a child. Parents need to be educated, and then educate your children. At the end of the day when the game is over and the tailgate parties end you can be left with a broken child who needs your help more than ever.

Please consider Kurt’s story and how it might apply to the role sports play in your family. Consider making a donation to the Concussion Legacy Foundation so that they may further advance the understanding of traumatic brain injury and the impact it can have. The work they are doing is so important. They have been a constant source of support for my family. Because of them, you won’t have to tell a story like mine because now you know more than I did.

Clyde L. Scott

My father Clyde Scott was an extraordinary athlete who lived a long and productive life. He died in 2017 at the age 93 after a long battle with dementia. After his passing, we were surprised to learn that he was diagnosed with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

In February 2000, the state’s largest newspaper The Arkansas Democrat Gazette declared Clyde Scott Arkansas’ Athlete of the Century (1900 – 1999). They called his sports resume impeccable and undisputable. It is easy to see why.

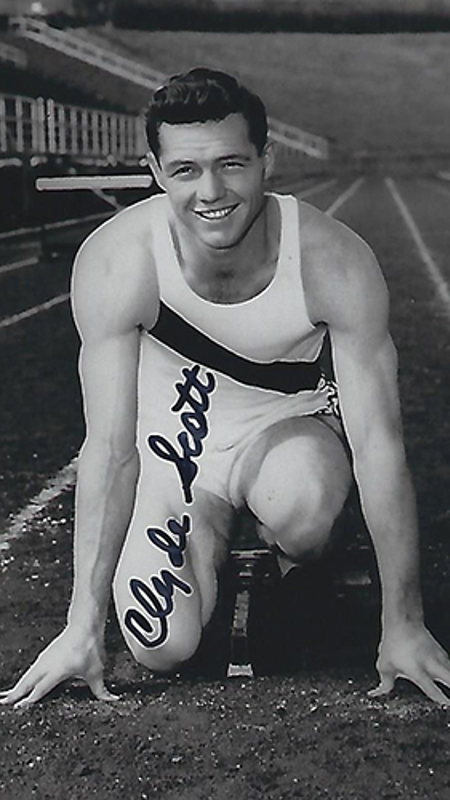

Clyde was an All-American at two universities and at two sports, held two world records in track, won a gold medal at the NCAA championships, a silver medal at the 1948 London Olympics, was a first round NFL draft pick, played four seasons and was on two World Championship teams (1949 Eagles and 1952 Lions). He was considered one of the greatest athletes of his time.

Clyde was born August 29, 1924 in Dixie, Louisiana, the third of ten children. His dad was an oil field worker. Clyde first gained notoriety in high school on the football field, but he also ran track where he set a number of state records. In the summer, he played baseball which he always considered his best sport. The St Louis Cardinals offered him a contract his senior year. Clyde loved baseball but wanted to go to college.

With the help of some businessmen in his home town, he received an appointment to the US Naval Academy. He played football for the Midshipmen in 1944 and 1945 and was named a second team All-American in 1945. At the time, Navy was the second best team in the country. He also ran track at the Academy where he set Academy records in the 100 dash, 220 low hurdles, 110 high hurdles and the javelin. In 1944 and 1945, he was the Academy’s undefeated light heavyweight boxing champion.

After football practice one day in 1945, Clyde had the good fortune to meet Miss Leslie Hampton from Lake Village, Arkansas. She was the reigning Miss Arkansas visiting the Naval Academy for a tour. His roommate was scheduled to be her escort but was called away on a cruise and Clyde was asked to fill in. They met, fell in love, and decided by the end of the school year they wanted to get married. With the war having ended, Clyde made the decision to resign from the Academy. That summer he was visited by coaches from around the country including Bear Bryant at Kentucky and Johnny Vaught at Ole Miss. He was recruited to come to the University of Arkansas by head coach John Barnhill, where he ultimately decided to continue his football career. The fact that his bride-to-be was attending the U of A may have influenced his decision to join the Razorbacks.

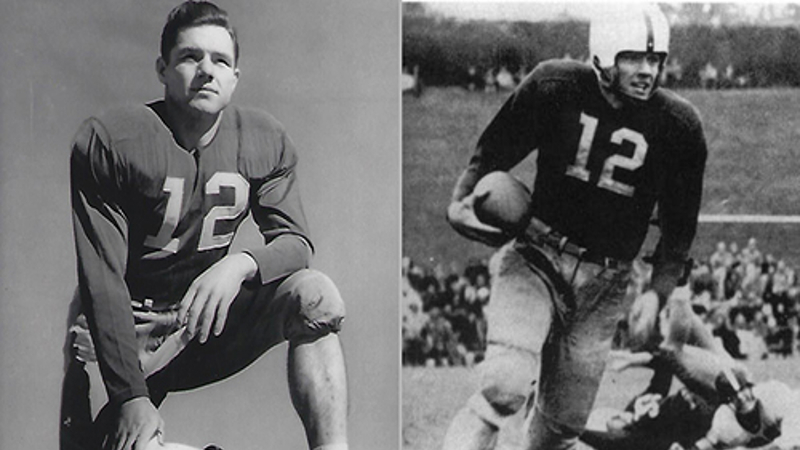

At Arkansas, Clyde was named All-Southwest Conference in 1946, 1947 and 1948, a second team All-American in 1946 and a first team All-American in 1948. His jersey number 12 was retired after his graduation. Clyde also wanted to play baseball, but his coach would not allow it. He did permit Clyde to run track where he set school records in the 100-yard dash, the 220 low hurdles, the 110 high hurdles, the 440-yard relay, and the javelin. In the 1948 NCAA Finals he tied the world record in the 110 high hurdles with a time of 13.7 seconds. That summer he made the U.S. Olympic team in the 110 high hurdles and went to the 1948 London Olympics where he won the silver medal in a very close finish.

Clyde was drafted in the first round of the 1949 NFL draft by the Philadelphia Eagles. He played three seasons with the Eagles and one season with the Detroit Lions. He battled injuries throughout his professional career and was forced to retire after the 1952 season.

Having lived such a long life, my dad would seem to be an unlikely candidate for the CTE brain study. His cognitive problems began when he was in his 80’s, much later in life than would be expected. Having a 93-year-old suffer and die with dementia did not seem that uncommon. Credit his wife of 72 years, Leslie, for making the decision to donate his brain to the study. She had seen some press coverage of the CTE study being conducted at Boston University and heard that the researchers were especially interested in brain donations from former NFL players. She realized it was an important study. After talking it over with me and my sister, the family decided to pledge my dad’s brain for research through the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank research registry prior to his death.

After his death, the efficiency of the donor program was very impressive. His brain was in Boston within the first 24 hours. Over the next several months, researchers gathered detailed information on dad’s life and sports career. You could tell that everyone we dealt with in the program was very committed to their work.

It came as a big surprise to the family that the study found dad had stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The reporting doctor said they found evidence of CTE throughout his brain which had also shrunken considerably.

Looking back, we realized there were signs that fit the CTE profile. He did not become aggressive or suffer from depression, but he did become extremely paranoid. For years, he had several irrational fears he had a very hard time dealing with. He hallucinated and had recurring nightmares. It made his life very difficult. It was also very hard on his family, especially his wife. Thankfully, the paranoia went away in the later stages of his dementia.

Dad’s mother lived to be 102 and maintained her wit and intellect to the end. His dad died of emphysema at the age of 96. There was no history of dementia in his family. How many years of meaningful life did he lose to CTE? I suspect a couple of decades but of course we will never know.

Would he have played football if he had known what may be coming? I never got to ask him that question. Football got him out of poverty, gave him an education and helped set up a successful business career, so I expect his answer may well have been yes. I do know he never encouraged me or my son to play football. Would he be glad to be part of this important study that may encourage others to avoid that dangerous path? Knowing what we know today, I have no doubt he would say “yes” to that.

Richard Seierstad

Curtis Sellick

Chad Short

Charles “Bubba” Smith

Read this excerpt from Spartan Verses by Pat Gallinagh; edited by Jim Proebstle, author of Unintended Impact.

Pat and Jim were teammates of Bubba’s at Michigan State University during the 1965 and 1966 seasons, when they won back-to-back National Championships.

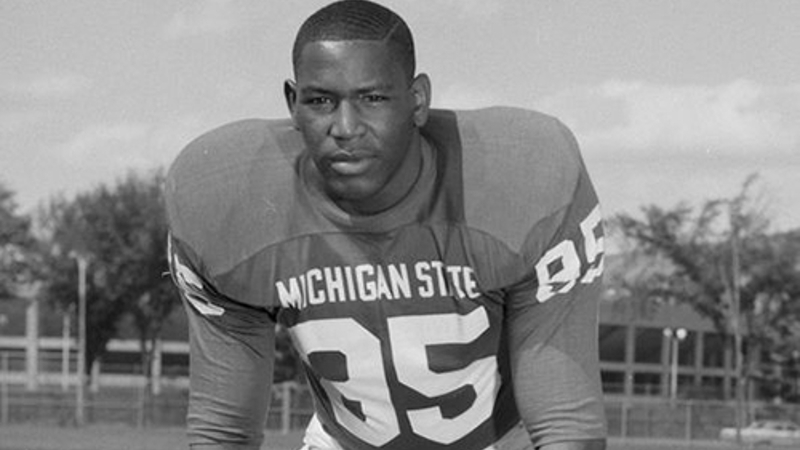

Every now and then you run into a character who is “bigger than life.” Charles “Bubba” Smith of Beaumont, Texas at 6 ft. 7 in. and 270 lbs. did both literally and figuratively fit that mold. Bubba was a passenger on the “underground railroad” of talented black athletes from the Jim Crow south that prohibited players from playing in the South. He, along with many others, was actively recruited by Coach Duffy Daugherty of Michigan State University in the sixties in what was to become one of Duffy’s hallmark achievements. Given a choice, Bubba probably would have preferred playing at a major university in his home state, like the University of Texas or Texas A&M.

By far the biggest member of the Spartan freshman football team in 1963, it was impossible for him to blend in with the thousands of new students pouring into East Lansing from all over the world. He stood out like a giant oak in an apple orchard. Many students stared at him in disbelief and rather than shy away from the fact that he was a behemoth, Bubba played the role to the hilt using his comedic talent to pretend to be a dim-witted, bumbling, good-natured oaf. A skill he would parlay into a successful acting career in Hollywood. He was a teaser and practical joker pushing his teammates’ buttons and his coaches to their limits with his pranks. In reality, Bubba was a good friend to those around him and never actively sought out the notoriety that just naturally presented itself.

There were some members of the college community who thought football players were modern day Neanderthals who dragged their knuckles on the ground as they prowled the campus. Others felt the football scholarships were a form of color-blind affirmative action for the intellectually challenged. Bubba was neither uncivilized nor stupid, although his persona did often catch the attention of the administration and coaching staff as his celebrity peaked during his senior year. The many Bubba sighting and urban legend stories that still exist to this day on the MSU campus are telltale of a man who easily adapted to the “big stage.”

With his enormous physical talent, he was often accused of not using it to the fullest on the field. There may have been some truth to that at times, but if so, it probably had more to do with peer pressure than not making an effort. When you are the biggest kid in your class you are often chided for using your superior strength and size by your classmates. Being labeled a class bully was not a coveted title back then or now, so unless prodded to do so by teammates or coaches, he sometimes may have appeared that he wasn’t trying very hard. And, it may have been because he didn’t have to. We should ask Terry Hanratty, Notre Dame’s QB who was permanently knocked out of the 10-10 Game of the Century, what he thought after a crushing tackle by Bubba in 1966. In any event, most teams ran their offense away from him as the fans in the stands chanted, “Kill, Bubba, Kill.” In the locker room Bubba was a very unique actor and just one of the guys adding tremendous chemistry and humor to a determined team of athletes.

The pros knew what they were doing when he was selected as the number one draft pick in 1967. He helped lead Baltimore to two Super Bowl performances in his five years with the Colts, winning Super Bowl V in 1971. After the Colts he spent two seasons each with Oakland and Houston. As one of the best pass rushers in the game, Bubba often drew two blockers, yet was effective enough to make two Pro Bowls, one All-Pro team and be recognized through the Vince Lombardi Trophy. Bubba Smith was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1988. The Big Ten Defensive Lineman of the Year Award bears his name. It is not documented to what extent he experienced concussions during his playing years. Clearly, there was significant punishment. What is known, however, is that the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) discovered in Bubba’s brain by neuropathologists at Boston University Medical Center was classified as Stage III CTE with symptoms that included cognitive impairment and problems with judgment and planning. Bubba died on August 3, 2011 at the age of 66. Smith was the 90th former NFL player found to have had CTE by the researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank out of their first 94 former pro players examined.

He was likely on his way to the NFL Hall of Fame until landing on a sideline marker in an exhibition game that curtailed his playing career and headed him into his acting career. Between 1979 and 2010, Bubba appeared in various roles in over twenty-two movies and television performances. Probably his most noteworthy efforts came in his role of Moses Hightower in the Police Academy movies and his role with Dick Butkus in the “taste great…less filling” Miller Lite commercials. It was this beer commercial contract that led to his proudest moment. When he realized that he was being used as an instrument to promote drunkenness; he walked away from his contract. His matured social consciousness took both strength and courage to break such a lucrative deal. He valued integrity over money. In the final analysis he was just Bubba: friendly, easy to approach, generous and never getting “too big” as a result of his success.

Bubba Smith is survived by his son, Nathan Hatton.

Chris Smith

Dave Smith

Fred Smith

Fred, my beloved husband of 43 years, was an awesome husband, father, grandfather, and friend. To us who loved him, he was extraordinary. But in his love for playing the game of football, he was quite ordinary and like so many other men and boys.

It is my hope that Fred’s story will give another human face to CTE, the devastating, but preventable, dementia caused by head trauma. I hope that Fred’s story will encourage parents, coaches, players, and medical professionals — whole communities — to support the work of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the BU CTE Center. And, finally, I hope his story will help former players and families struggling to find answers to bewildering changes.

CTE caused my Fred to change so subtly and so slowly, but so remarkably, over time that it’s hard to remember the Fred of our beginning and impossible to pinpoint the moment CTE laid its claim.

Fred and I met in college, the unlikely story of a blind date going well. . . his roommate dating my roommate. We were Navy brats who shared a love of traveling. We raised two fine sons, Shayne and Jeremy. We were supported by family and blessed to gather lifelong friends along the way, many attracted by Fred’s warmth and humor.

Anyone who met Fred for the first time knew immediately that he loved people. He drew people to him with his mischievous sense of humor, wry smile, and pranks. He never failed to bring a smile to those he lured into his practical jokes. He was fun and could engage strangers whether in a village along the Amazon or in a checkout line at Kroger’s. Who else could entice a couple on the eve of their wedding to abandon their wedding party to join us strangers for a few hours of laughs? He was the proverbial “people person.“ Fred’s humor drew people to him, but his honesty, compassion, and unpretentiousness kept them there.

Typical of many boys, Fred grew up with a love of sports, particularly football. At Elkton High School in Virginia, he played football (All-State), basketball, baseball and track. At Virginia Military Institute he played left tackle on the football team for four years. He said he went to college to please his parents, but stayed to play football. He shrugged off “getting his bell rung” as just part of football. In a televised game, he was taken from the game after a hard hit and returned minutes later. . . but joined the huddle of the opposing team. A picture of this play in a local newspaper is a haunting reminder of that day. Once seen as a humorous memory in his mother’s scrapbook, it now represents the kind of hit that had potential long-term consequences.

After graduating from VMI in 1969 with a B.A. in Economics, Fred served as an Army Field Artillery officer for 10 years, beginning with a tour in Vietnam where his men would later describe him as a respected leader: caring and calm under fire. These qualities were used to describe Fred repeatedly throughout his military career. Fred’s last assignment took us to Germany where Fred jumped at the opportunity to join a rugby team. The oldest and least experienced on the team, he played with fervor and enthusiasm but, unfortunately, in the style of football which led to several concussions.

In 1979, Fred left the Army to pursue a new career in sales. During the next 20 years, he worked for several companies in the paper industry, and eventually worked himself into management.

Along the way, there were nagging concerns about very subtle changes in judgment, temper, and confusion in doing seemingly simple tasks. Things just didn’t seem right. And Fred’s long history of headaches seemed to worsen.

Gradually, the early hints of something wrong evolved into serious mistakes, hostility to those whom he disagreed with and confusion, particularly in math, problem solving and organizing. He had trouble writing coherently, learning new computer software, and using his cell phone. He began having night terrors and would yell out that people were trying to get him. Early neurologists and imaging found nothing wrong. . . and, as we would be told often in the coming years, his “memory” was great.

In the last two years that he was employed, Fred was demoted from general manager to sales manager to salesman, and finally to dismissal. Confusion and inappropriate responses in interviews cost him any chance of getting another job. Neurologists attributed these changes to depression from losing his job, but antidepressants didn’t stop the declines. Fred recognized that he had trouble with word finding and with learning new things, but rejected any other suggestion of personality change.

The night terrors and an obsession with watching war movies took us to the Veterans Administration in 2006 where Fred was screened for PTSD. Fred’s ability to communicate and remember events 36 years in the past were iffy at best by then, so the screener did not see PTSD; but he did see that something was definitely wrong and suggested more testing. After years of searching for answers, Fred received a tentative diagnosis of a dementia that, like CTE, begins with behavioral and personality changes. By this time, Fred’s mounting frustration turned to frequent angry outbursts.

When research started emerging about a kind of dementia that could be caused by concussions and repetitive hits, something clicked. Was it possible that Fred’s years playing football and rugby had caused his dementia. CTE wasn’t a dementia Fred’s early neurologists recognized as a possibility. And I was initially skeptical, too, since most of the first cases of CTE had been found in elite professional athletes, athletes who had played much longer and at a much higher intensity than Fred had. After all, if Fred did have CTE, how many thousands of Freds could be out there. What a truly horrifying possibility!

The boys and I needed to know the truth, and I was absolutely certain that Fred would want that too, so Fred became part of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center brain donation program.

CTE took Fred little by little, one ability after another. It was especially hard on him because he understood on some level and was often scared. He knew us to the end even though he had lost his ability to think, talk, and walk. I miss him terribly, but know how blessed we were to have had so many years of fun, adventure, and love, the memories of which will last a lifetime. And although our grandchildren never got to know their fun and loving grandfather, I am comforted knowing that the best of Fred lives on in our sons.

As hard as his illness was, the confusing years searching for answers and then the heartbreaking steady declines, the real tragedy was that Fred’s death from CTE was totally preventable.

Those of us who loved Fred are comforted that Fred’s death and story may help researchers learn more about CTE. . . Perhaps to find markers and educate doctors which will lead to earlier diagnoses and thus shorten the anguished years of not knowing. Perhaps to sound the alarm about the potential epidemic among us. . . Perhaps to alert parents, players, and coaches of youth contact sports to listen to the research. . . and perhaps to save another typical young person from living Fred’s story.

I can’t thank the researchers at the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center enough. Their dedication not only for uncovering the depth of the problem but also for searching for solutions is inspiring. Thank you, Dr. McKee, Dr. Stern, and Chris Nowinski and the staffs at CLF and BU for giving Fred’s family and friends the peace of finally knowing and the opportunity to help others.