Matthew Traverso

Max Tuerk

Max Tuerk was a force to be reckoned with from birth: he came into the world a whopping 9 pounds, 8 ounces, ready to make his mark. His massive smile lit up his face. He was gregarious and outgoing. He was never hesitant nor fearful and jumped into new experiences with excitement and an eagerness for adventure. Max loved to be around people and had many friends. He was known for his warmth, loyalty, and fun-loving spirit. He had a personality to match his size.

Under the smile and playful, adventurous spirit, was a will of steel. He knew what he wanted and was relentless in pursuing his goals. In middle school, he secretly carved “USC – NFL – HOF” onto his desk. He was able to achieve two of those lofty goals during his short life.

Max was very close with his siblings and was unquestionably the leader of the Tuerk squad. He was sometimes affectionately called “Officer Max” because he always kept Drake, Abby, and Natalie in line! He was fiercely loyal and was their mentor and protector. He always encouraged his siblings, especially in sports. He loved to watch a fierce competition as much as he loved to participate in one – once offering Natalie $5.00 if she could get a red card in soccer! Max had special relationships with his parents as well. He bonded with his dad over sports, competition, grilling, and beer. He and I enjoyed travel, adventures, and playing games together. As anyone who knew Max can attest, he loved to eat and appreciated good food. It was a true pleasure to cook for him and we shared many wonderful meals as a family.

Beyond his determination, Max’s defining characteristic was his loyalty. He was devoted to his family, friends, teammates, and coaches. He loved football, not for fame or for money, but for the camaraderie and bonds he established with his teammates, whom he considered brothers. He had zero tolerance for negativity or backbiting, which he would quickly squelch. He never complained about coaches, playing time, or teammates. He was known to stand up for the underdog on the team. This is one of Max’s most important legacies: every time we find ourselves gossiping or criticizing, we remember Max and pause. We want to live up to the high standards he set.

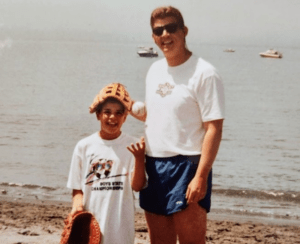

Max loved sports from an early age – any sport, any time. He just loved to be part of a team and to be with his friends. He started out in taekwondo, soccer, and baseball, but found his true love when he began playing tackle football in the 4th grade. Max was the ultimate competitor. He never took a play off. He gave every bit of himself to his game and inspired those around him to do the same. He was a natural leader who inspired confidence in teammates and coaches.

Football came to dominate Max’s life in high school, and it became clear he was blessed with great talent to go with that amazing determination and work ethic. Max helped lead his Santa Margarita High School Eagles to win the State Championship his senior year, playing both offensive tackle and defensive end. He was selected as an Army All-American his senior year and received 30 D-I football scholarship offers. Max signed with USC, ticking the first item off the list he carved into his desk years before.

Max made history at USC as the first freshman to start at left tackle. Max’s first game at left tackle was also coach Clay Helton’s first game as offensive coordinator, and it was a big one against Oregon in the Coliseum. Coach Helton was a bit nervous before the game and asked Max, “Are you going to be OK?” Max smiled and assured him, “I’ve got you, Coach.” There Max was inspiring others, as usual.

Throughout his USC career, Max played all five offensive line positions. He was admired and respected by his teammates and was twice voted team captain. Although there was a great deal of turmoil at USC during his time there, including multiple head coaching changes and a different offensive line coach each year, Max loved USC and was a true Trojan. He made wonderful friends, joined a fraternity, and fell in love. Unfortunately, Max’s senior season was cut short when he tore his ACL against Washington on October 8, 2015. Not to be deterred from fulfilling his dream to continue in football, Max decided to leave USC to prepare for the NFL draft. Despite his injury, Max was selected by the San Diego Chargers with the 66th overall pick in the 2016 NFL draft. The second item on his list was checked off.

We first noticed changes in Max’s behavior after the draft. Normally outgoing and gregarious, Max began to isolate himself and stopped communicating with his family. This concern intensified once Max moved to San Diego with the Chargers. He became extremely paranoid and suspicious, and his behavior turned increasingly erratic. The move from the camaraderie he had known and loved his whole life to the world of professional sports was a challenging transition. He was convinced that members of the Chargers were trying to sabotage him and his paranoia soon extended to his family. He began to believe we were collaborating with his enemies to harm him.

This behavior was extreme, alarming, and confusing. Initially, we worried drug use was causing this erratic behavior. But it soon became clear Max was experiencing a mental health crisis. Max’s mental illness led him to make choices that were extremely detrimental to his future. To make matters worse, he had no insight into the fact he was ill, which absolutely devastated us. We wanted nothing more than for Max to get the help he so desperately needed, but he was unable to recognize he needed help. Instead, he thought we were trying to harm him. All those years of playing through the pain and refusing to acknowledge any weakness had made it virtually impossible for Max to ask for or accept help.

He continued to isolate himself from his family, friends, and support system. In this altered state of mind and in isolation, he sought alternatives to enhance his chances of success in the NFL, leading to his choice to take performance enhancing drugs. This was completely out of character for Max and led to his suspension by the Chargers before his second season. At this time, Max was persuaded to see a psychiatrist, who prescribed Max with antipsychotic medication. The medicine did seem to help Max for a time. He was dropped to the Chargers practice squad after his suspension but was picked up by the Arizona Cardinals and looked to make a fresh start. But the second season unfolded much the same as the first. Max was simply not the same physically or mentally and at some point, stopped taking his prescribed medication. He was dropped by the Cardinals after the 2017 season.

Max returned home to southern California and tried to remake his life. His symptoms made it difficult for him to maintain a job – he struggled with hallucinations, psychosis, and extreme depression. Although still lacking insight into his condition, he was aware something was seriously wrong and made every effort to take care of himself. He believed he could fix what was going on in his brain and was extremely disciplined about his food intake and exercise. He had always been able to take care of things on his own. Why should this be different?

Max’s symptoms became increasingly severe and could not be managed without medication. Max had several serious incidents and was hospitalized twice. The second hospitalization was triggered by threats of violence to his family. Max was not violent before this incident and had always been considered a gentle giant. This was devastating for all of us, but particularly for Max. He could no longer recognize himself. He had been the protector of family and friends his whole life. This was not who he was. Finally, Max gained insight into his illness and voluntarily accepted treatment.

Max approached treatment as he approached everything in his life, with steely determination. He was going to have the life he dreamed of and deserved, and we were filled with admiration watching him fight. He had to deal with paranoia, psychosis, hallucinations, and a depression he described as the deepest darkness he had ever faced. He also dealt with mental fog, headaches, and what we later found out to be cardiac symptoms. He was battling a mental illness while watching everything he had ever dreamed of evaporate before his eyes. Max’s pain was unbearable and excruciating for our family. The mental demons Max faced were wreaking havoc on him, but he puffed out his chest and “fought on.” He never complained or despaired. He believed he would be able to get his life back.

Max managed his mental health and maximized his new reality. He was working part time, going on daily hikes with me, eating, exercising, and taking care of himself. We know he was struggling with all of this, but he was very stoic and never let on that he was in pain.

On June 20, 2020, Greg, Max, and I took a beautiful hike together. Max collapsed on the trail. Paramedics were called and helicopters arrived, but Max died on the trail with us. We learned after his death that he had an undiagnosed cardiac condition known as cardiomegaly, or an enlarged heart, which caused his death. His death was a tragic loss and has left a gaping hole in our lives. But we feel comforted that he was in a beautiful place doing something he loved, with the people who loved him most in the world.

We were looking for answers in the dark days of Max’s mental illness – why was this happening to this proud and capable young man? We knew something was terribly wrong with his brain but there was no help to be found. No one understood what was happening and no one could help Max when he did not want help. We suspected Max had CTE and Greg reached out to Dr. Chris Nowinski at the Concussion Legacy Foundation for help in these dark days. Chris provided warm understanding and helped us to feel a bit less alone.

When Max died unexpectedly on that trail, one of our first calls was to Chris to arrange for Max’s brain donation. We hoped and prayed we could get to the bottom of what had happened to our beautiful, strong boy. Max’s brain was studied by Dr. Ann McKee, and he was diagnosed with stage 1 (of 4) CTE. In addition, his brain showed significant white matter damage and there was a cavum septum pellucidum between the hemispheres of his brain. His brain had been damaged by all the years of impact he sustained playing the sport he loved. We were not surprised as we knew something was dreadfully wrong in Max’s brain.

Max never had a diagnosed concussion, but there is no doubt he had several. Sometimes after a particularly tough game, he would seem unusually sad, quiet, and aloof. Of course, he never acknowledged that anything was wrong or he was in pain. Once he was in the NFL, he had debilitating headaches and would require darkness and silence. But more important than these probable concussions, he experienced nonconcussive head impacts repeatedly from the age of nine. As a lineman who played offense and defense until reaching college, Max’s brain absorbed hit after hit, setting the stage for the disease that would take everything from him and take him from us.

Football was Max’s life. But that love cannot begin to compare with the pain and suffering he experienced at the end of his life. It was absolute hell physically and emotionally. And we now know it was all preventable. He could have played the sport he loved in a much safer way. He could have played flag football until he got to high school, saving his brain from the countless hits he absorbed between fourth and ninth grade.

Max and I hiked daily in his final months of life, and I feel very connected to him each time I walk on “our trail.” One day when I was hiking, I felt Max speaking to me very loudly – my determined boy had something to say. I dictated these words on the trail; I have never written a poem in my life, and I am certain this came directly from Max and was meant to be read and to make a difference:

They are born with the heart of a warrior.

That heart swells with the words of those around them:

“Play through the pain”

“Take one for your team”

“Never give up”

And their brain responds.

This is who they are. They are buoyed by the words of those around them:

“You’re a leader”

“You’re so strong”

“Never show weakness”

“You’re a beast”

You understand that you cannot stop to answer the call of pain. That would be a weakness and above all, you cannot show a weakness.

Your brain takes this in and adapts.

They make you a hero. A star. Everyone knows your name.

It creeps in slowly.

Headaches that won’t go away. The confusion. The blackouts. How can it be there? That doesn’t happen to you.

You continue to play, but your shimmer slowly starts to dull.

You understand there’s a tangle inside your brain. Something isn’t right. But that same strength of character that led you to excel will not allow you to ask for help.

Eventually, the monster inside your brain robs you of everything. You can no longer do what you love. You can no longer trust those around you. You are in so much physical and mental pain.

You are so very, very alone.

Your suffering is immense.

Everyone who made you into a hero are quick to turn away.

The fame is ephemeral. And the cost was immense.

The very sense of self at its core is shattered from the pinnacles of success to the depths of despair.

To be so capable and successful and to be reduced in so many ways. It’s just intolerable.

The monster.

Dave Van Metre

Dave Van Metre was a tremendous athlete, a lifelong learner, a gifted educator, a lover of both people and animals alike, and above all, a tremendous husband and father.

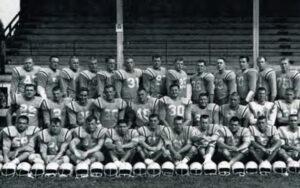

Van Metre grew up in the Midwest and was immersed in sports from a young age. He went on to attend Cornell University, where he was a two-time Academic All-American and a second-team All-Ivy defensive lineman his senior season in 1985. Van Metre was a diligent student and earned his undergraduate degree from Cornell in 1986 before earning his Doctorate of Veterinary Medicine degree from Cornell in 1989. His education continued at UC Davis, Washington State University, Kansas State University, and finally, Colorado State University.

He became a livestock veterinarian and faculty member at the CSU James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital for 20 years. He was beloved by his students at CSU and was given the Zoetis Distinguished Veterinary Teaching Award for a faculty member providing outstanding veterinary education in three separate years.

“They know more than they think they know. That’s the most rewarding thing for me,” Van Metre said about his students.

Van Metre loved his work, but his greatest love was for his family. He enjoyed nothing more than spending time with his wife, Dr. Robin Van Metre, and his two sons, Aaron and Joe. He delighted in watching Aaron and Joe succeed in their various activities, athletic and otherwise.

Van Metre was a true team player – in sports and in life. He left it all on the field and devoted that same energy to everything else in his life. He did his best to uplift and elevate everyone he met. Tragically and unexpectedly, Van Metre succumbed to anxiety and depression and took his life on April 1, 2019. He was 55 years old. His death was a complete shock to all who knew him. While a comprehensive neuropathological examination could not be performed, the ME reported they observed some changes consistent with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

While those closest to Van Metre saw him as seemingly thriving, he was fighting a silent battle no one knew about. His tragic loss is a testament to how suicide is a complex public health issue and involves many different factors. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide most often occurs when stressors exceed current coping abilities of someone suffering from a mental health condition.

Suicide is preventable. You are never alone, help is available and healing is possible. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. You can also connect with the Crisis Text Line by texting ‘HOME’ to 741-741.

If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis.

Van Metre loved the game of football. He played with his entire heart, soul, and body. He often referred to his Cornell Football days, and his comrades as the best of his life. The Van Metre family is grateful for CLF’s efforts to create Smarter Sports and Safer kids so that so many kids can still reap the valuable benefits from their participation in sports.

CLF’s Education & Advocacy programs seek to improve sports, not eliminate them. Research from the UNITE Brain Bank has moved the CTE conversation beyond boxing and the NFL, and directly inspired safety reforms for children. After researchers diagnosed the first NHL player with CTE in 2009, USA Hockey banned checking up to age 13. Similarly, after researchers diagnosed the first American soccer player with CTE in 2014, US Soccer banned heading until age 11. CLF’s Flag Football Under 14 campaign seeks to make the football ecosystem safer by encouraging parents to delay their child’s enrollment in youth tackle football until their brain and body is mature enough to play.

Derek Van Slyck

Tommy Vaughn

A historic career

Tommy Vaughn grew up in Troy, Ohio as the oldest of five children and shouldered the responsibility that many eldest siblings are dealt. Vaughn had to help care for his young siblings but still found time to play sports with neighborhood friends. He started playing tackle football in local parks when he was seven years old.

Along with football, Vaughn lettered in baseball and basketball at Troy High School. While he received scholarship offers for all three sports, he followed his love of football and accepted a scholarship to Iowa State University. There, he would become the Iowa State Athlete of the Year in 1963 and an Academic All-American in 1964.

For his athletic accomplishments, Vaughn would later be inducted into the respective Hall of Fames for The City of Troy, Iowa State University, and Troy High School.

After his decorated college career ended, Vaughn was drafted by the Detroit Lions and married his college sweetheart, Cynthia, in 1965. They had two children, Terrace and Kristal.

Vaughn never missed a game in his seven-year career in the NFL. During those seven years, there were three times he woke up in a hospital room after being knocked out in a game. After the third knockout, a doctor warned him of the dangers of continuing to play if he suffered more concussions. In 1972, Vaughn chose his health and his family over football and retired at the age of 29.

Life after football

Growing up, Vaughn was raised to be humble. Despite being an NFL star, Kristal Vaughn says she never saw her dad think he was better than anyone else. He always made time to sign autographs for young fans and his bright personality followed him wherever he went.

When she speaks about her dad, she remembers him far less for his football accolades and much more for his kindness and intellect.

“He was an intelligent, happy, nerd,” said Kristal. “He was like Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory, but athletic.”

Vaughn enjoyed a robust life after football. He acted in the movie Paper Lion, earned his master’s degree, was a general manager at the Chrysler Corporation in Detroit, the President of Union National Bank of Chicago, and a high school teacher. Despite his success in business and education, Vaughn couldn’t stay away from the game for long.

“He loved teaching the game,” said Kristal. “My dad was the most giving, caring person in the world.”

He became an assistant coach of the World Football League’s Detroit Wheels and then later for his alma mater at Iowa State University, the University of Wyoming, the University of Missouri, and Arizona State University.

Later, Kristal heard from many of Vaughn’s former players and students. Many of them told her about how coach or Mr. Vaughn never gave up on them.

Much to his dismay, Vaughn often worked long hours in coaching. After a long day, Vaughn often woke his children up to bake pies. The activity served two purposes: squeeze in precious family time and satisfy his legendary sweet tooth.

“I never got to know my real daddy”

For all the wonderful moments the Vaughns shared together, their household was not always a safe place.

Shortly after Vaughn retired from the NFL, his family noticed him become more anxious. Kristal remembers her father’s anxiety first manifesting into violent outbursts. She says her father always had a soft spot for animals, but he began taking his anger out on the family dog.

As Vaughn’s symptoms progressed, Kristal says his anxiety and agitation led to physical violence toward her mother and siblings.

When Vaughn moved the family from Detroit to take a coaching job at ISU, Kristal says her parents separated for six months because Vaughn didn’t resemble the man her mom Cynthia fell in love with.

The type of man Cynthia once knew was one their children would never get to meet.

“I never got to know my real daddy,” said Kristal. “And that’s not fair.”

When the family was in Iowa, Vaughn was prescribed medications to help manage his symptoms. Terrace caught on that his father was taking “puppy uppers” and “doggy downers” to regulate his emotions and behaviors. He told his sister to remind their father to take his pills if he was acting out. Tommy Vaughn was later diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

To cope and to protect herself, Kristal learned from a young age to remove herself from the situation whenever things at home became hostile. A self-described nerd herself, Kristal found refuge in books at her local library.

“I learned to not try to soften it,” said Kristal. “Don’t get involved with it, let them have their moment. Things will calm down.”

In 1985, Vaughn took a coaching job at Arizona State University. While in Arizona, Vaughn’s short-term memory began to decline. Kristal remembers her father would frequently repeat himself but would deny the repetition when anyone brought it to his attention.

Through her role as a social worker at a rehabilitation center that served brain injury patients, Cynthia gained a better understanding of how to work with her husband’s symptoms. She encouraged him to begin seeing a psychiatrist in Scottsdale who prescribed better medications to help stabilize Vaughn’s behavior.

Medications helped, but only to a point. Vaughn’s verbal filter disappeared over time, leading him to say vulgar or hurtful things to those around him, only to forget he said them minutes later. This pattern led his wife and children to follow the motto of, “if he didn’t remember, it didn’t happen and move on.”

As Vaughn aged, his mood swings and behavioral changes took a turn for the worse. In his late 60’s, he was the lieutenant governor of the Optimist Club youth program in Arizona. Every week, Optimist Club leadership met for breakfast at a local diner. One day, Vaughn misinterpreted a comment a waitress made and threatened her. Management asked Vaughn to leave and to never come back.

Vaughn suffered from panic attacks for much of his post-football life. At first, the episodes occurred every few months. By 2013, the attacks became weekly occurrences, usually triggered by trivial matters.

In 2015, Cynthia decided to bring Vaughn to the Barrow Institute in Phoenix, Arizona where he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Vaughn had been on a progressive downslide for years, but his football career and extensive concussion history was never discussed as a culprit until he reached his early 70’s. Vaughn began to connect the dots between the repetitive head trauma he endured throughout his football career and the symptoms he struggled with for much of his life. He later told his family he wanted his brain to be donated to the UNITE Brain Bank for CTE research.

As things worsened, Vaughn’s family desperately needed support to help manage his declining condition. That support came from an NFL contemporary of Vaughn’s.

“I have to be grateful for the 88 Plan,” said Kristal. “There is help out there. You’re not by yourself.”

The 88 Plan is named after Hall of Fame tight end and Legacy Donor John Mackey, who wore number 88 in the NFL and played in the league with Vaughn. Mackey died in 2011 after a long battle with what was eventually diagnosed as CTE. His public struggle with the disease led to the 88 Plan, which provides $88,000 a year for families of former players living with dementia.

Eight months after starting to receive 88 Plan benefits, Vaughn died at age 77. His family fulfilled his wish to have his brain studied, and Brain Bank researchers posthumously diagnosed him with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE.

“Do you guys get this?”

After she learned her father had CTE and not Alzheimer’s, Kristal was immediately taken back to a traumatic memory.

Kristal has a history with traumatic brain injury herself and suffers occasional seizures as a result. Once, in the last years of her father’s life, she was coming out of a seizure, laying down on the floor. She came to as her dad was pounding her head into the ground, screaming at her to wake up. In the chaos, Vaughn got frustrated at Cynthia and struck her as well.

“30 years ago, he would never have done that,” said Kristal. “He had the biggest, most beautiful heart.”

To other families with loved ones affected by possible CTE, Kristal wants to ensure they never abandon their loved one, but to also always prioritize their own safety. She says the lesson she learned as a child – to remove herself and to not engage with her father when he became aggressive – is vital to caregiving for someone with potential CTE. In her experience, her father would always calm down if given enough time.

She also urges those in power in the NFL to take player welfare more seriously and consider how a former player’s symptoms of CTE can devastate a family.

“I want to ask them, ‘Do you guys get this?’”

Despite the tremendous adversity she and her family have faced, Kristal retains an eternal sense of optimism. Her lasting message to other CTE families is one of resilience.

“We made it,” said Kristal. “We survived this. You can too.”

If you are being physically hurt by a family member or loved one, know it is not your fault and there is help available. For anonymous, confidential help, 24/7, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE).

Are you or someone you know struggling with symptoms of suspected CTE? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Mark Loys von Kreuter

Mark graduated from Darien High School in 1980 where he and his team were undefeated and won the FCIAC Connecticut State Football Championship. Mark then attended Choate Rosemary Hall as a post-graduate where he and his team also went undefeated winning the New England Prep School Football Championship. Mark was heavily recruited by numerous Ivy League colleges and attended Princeton University, graduating in 1985 where he majored in history, was a member of the University Cottage Club and was an outstanding defensive end for the Princeton Tigers earning three varsity letters during the ’82-’84 Tiger campaigns. Number 98 ruined many a fall Saturday afternoon for the visiting team at Palmer Stadium and was named Defensive Player of the Game against Bucknell. A true “son of Princeton,” Mark was happiest when going back to Old Nassau with friends and classmates, especially at football games and reunions.

Mark had a very successful career as an institutional equity salesman starting his career in New York at Smith Barney. During that time received his MBA from the Stern School of Business at New York University, attending classes at night and on weekends. Recently Mark was a partner at Capture Capital LLC where he worked raising institutional capital for a variety of hedge funds and private equity funds. He was hard working and made many friends along his career path. He was a member of the Racquet & Tennis Club on Park Avenue in New York City, the Noroton Yacht Club and Wee Burn Country Club in Darien.

Large in stature, but even larger in persona and generosity, Mark traveled the world to celebrate his many friends; a wedding in Rome, a U-2 concert in Dublin, several visits to Singapore to be with his godson who was fighting a rare disease resulting from treatment which cured his cancer, ski trips to Austria, golf in the British Isles, Italy and France, or a safari in Kenya. The underlying thing that made Mark so special is that these things were all done with and for his friends and family. He loved being there for people, especially his mother, his siblings and his ten nieces and nephews who adored him.

The last thing Mark did before he died was to write a letter to his mother, telling her how much he loved her and to have his brain donated for CTE research. We are honored to have Mark’s memory live on with the Concussion Legacy Foundation. While he shared his thoughts and concerns for CTE with his teammates, he kept these concerns to himself when it came to family and other friends, choosing to not be a burden. The six months of the pandemic leading up to his death took a toll on Mark. He left New York City for Connecticut to make sure that both he and his widowed mother were safe from COVID19. Family was always Mark’s top priority, and he would be very happy today in the knowledge that he succeeded in this regard as his mother is fully vaccinated. Mark was aptly called a “perfectionist in an imperfect world” but not one of his family members or his friends had any indication that Mark was suffering so much to take his life.

The outpouring of sympathy and love for Mark was and continues to be the measure of the man he was and will always be, bigger than life. Anyone who knew him is better for having known Mark and he will live in our memories forever.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Eric Wainwright Jr.

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering for some readers.

April Harrison and Eric Wainwright Sr. remember their son, Eric Wainwright Jr., or “E” for short, always looking into the future.

E was a son of football. Wainwright Sr. played college football and had a brief stint in the NFL before coaching college football. E was the ball boy for his dad’s Delaware State University football team when he was four years old.

He was too young to play for real, but young Eric couldn’t wait for his first games. When he was six, his parents noticed a horrific odor coming from his room. He poured water all over his carpet to simulate what it would be like to play in a rain game.

Eventually, little E got his wish and started playing tackle football when he was seven years old. His speed, strength, and coordination quickly earned him the de facto role perennially bestowed on the most gifted athlete on youth football teams: the star two-way running back and linebacker.

Eric developed his personality as an old soul. He’d make profound remarks about what he saw on television that would cause his parents to look at each other in amazement.

He moved from Delaware to Piscataway, New Jersey in middle school and spent his first years in high school there. But once again, E had his eyes on the next thing. He convinced his parents to send him to Cheshire Academy in Connecticut for a year and then to Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne, Pennsylvania. Eric wanted to go to Valley Forge because he thought he might be interested in military leadership one day.

E thrived at Valley Forge. At a school full of future leaders and on a roster of well-rounded athletes, Eric was named captain of the football team.

Football was not the only sport Eric found a team to uplift in his time at Valley Forge. He picked up lacrosse on a whim and excelled, participated in the school’s science teams, and was active in student government. His father described Eric’s way of being as being impressively nerdy.

“He had all the gifts,” said Eric Sr. “He was talented, gifted athletically, an extremely good orator, handsome, and charismatic.”

“He would bring people together,” April added. “He made folks happy.”

After Valley Forge, Eric attended and played football for Dean College in Franklin, Massachusetts for two years before a year at East Stroudsburg University in Pennsylvania. He then transferred to Wesley College in his home state of Delaware.

Eric quit football by the time he got to Wesley to focus on academics and internships. But even though he was done playing, the effects of nearly two decades of the contact sport stayed with Eric.

Eric’s father estimates Eric suffered five concussions in his football career, and countless more nonconcussive blows from playing the two positions most frequently involved in big hits.

“He always let us know when he had concussions,” said Eric Sr. “But it’s those nonconcussive hits that we weren’t really aware of. Those are the troublemakers.”

Eric made the most of his time in Delaware, interning for Senator Tom Carper. Over two years, Eric traveled up and down the east cost with Senator Carper, learning about government and the legal system. Eric also worked on the Clinton campaign in 2016, meeting future President Joe Biden in the process.

A product of public education himself, Eric knew firsthand how the system failed so many students, especially students of color, nationwide. His experience in first public then private education, coupled with his time around politics, inspired him to publish his own eBook in March 2016, titled The Miseducation of Poor Americans: A Legacy of Neglect and Deception.

By the time Eric graduated from Wesley in spring 2017, it had been years since his parents had seen him for an extended period; he hadn’t lived with either parent since his sophomore year of high school. When April and Eric Sr. visited him for graduation, they noticed Eric’s trademark ambition was starting to eat away at him.

Eric’s resume and acumen had him dreaming of scoring a perfect, high-paying job directly out of college. But when that offer didn’t come, Eric got anxious.

“He had done so much and done so well in college, he knew after graduation that he was going to go out there and get the job,” said April. “But it takes a while.”

He took a job as a management trainee for Hertz and was living with Eric Sr. back in Piscataway.

“I’m wearing a suit and I’m cleaning cars,” Eric Sr. remembers his son saying to him over the phone. “I’m not supposed to be here.”

Eric Sr. tried to console his son and preach patience, but Eric Jr. struggled to reconcile his current position with the hopes he had for himself. On top of his anxiety, Eric Sr. saw his son seek out dark places to manage his sensitivity to light and avoid headaches. Sr. always knew his son to command the attention of every room he entered. But when he lived with Eric he could see his son was concealing an inner pain.

“When I was able to watch him and be with him, that’s when I was like, ‘Wow, something’s wrong,’” said Eric Sr.

Eric Sr. has his own struggles with various effects of playing football. Through scans and evaluations at Mt. Sinai hospital, Sr. learned he has damage to the white matter in his brain, which can cause memory loss and depression, among other symptoms. At 27 years old, Eric Jr. spoke to his mother about hopefully entering the same evaluations his father had done.

His wishes for evaluation were not able to come to fruition. On August 24, 2018, Eric Jr. died by suicide at age 27.

A coroner came to the home and immediately asked Eric Sr. if Eric played contact sports. She suggested his brain be sent to the UNITE Brain Bank for research. Eric Sr.’s own familiarity with concussion, CTE, and the Brain Bank’s research made it an easy decision.

While suicide is a complex public health concern with no single cause, studies have shown an increased risk of suicide among those who have suffered a single traumatic brain injury. As April and Eric Sr. mourned the loss of their son and awaited the results from the Brain Bank, they reflected on the cascade of effects football can have on those who play it.

“As spectators of the game, we’re cheering on these guys,” said April. “But we’re not really thinking about what they are going through. This is an American sport that everyone loves, but players, coaches, parents, and spectators all have to be more aware of what it can do.”

For Eric Sr., his son’s tragedy raised internal questions.

“With this and what happened to some of my teammates who I played with over the years who took their lives as well, and with what I’m going through personally,” he wondered. “I’m like, was football really worth it?”

After months of research, Brain Bank researchers told April and Eric Sr. they did not find any lesions of CTE in Eric’s brain. They did identify evidence that Eric was suffering from neurocognitive issues due to a widening cavum between the left and right ventricles of Eric’s brain and the erosion of his myelin sheath, damage that usually precedes CTE formation in the brain.

Eric’s parents were not surprised to learn he had potentially worsening brain damage in his brain when he died.

“It gives the gift of closure,” said Eric Sr. “This helped bring some more understanding of why things had to happen like it did.”

Eric’s parents will forever miss the way their son could effortlessly improve their moods and bring light to everything he touched. They hope the ambition Eric held to improve the world can now be channeled in a different way.

Eric Sr. has been in and around football for most of his life. Sports provided him with an overwhelmingly positive experience he hopes every child experiences. But he doesn’t think kids need to play tackle football until they’re at least 14 years old.

Eric wrote a book on education reform. His parents hope his story can supply another chapter on the topic.

“There are a lot of families that think football is a way out,” said Eric Sr. “We have to dispel that myth. Let’s get them involved in STEM, along with a healthy athletic program. That’s what’s going to generate their income and improve their futures.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Steve Wallace

Last month would have been my dad’s 80th birthday. I miss him more than I can put into words. While I don’t miss the dementia, the decline, or the painful way his life ended, I deeply miss the man he was. He was my biggest fan and a huge source of my strength.

For years, my parents searched tirelessly for answers about his health. My dad, once the embodiment of strength and joy, began to slip away, leaving us confused and heartbroken. It started in 2015 with small signs: forgetfulness, confusion, and moments of anger. Doctors offered guesses such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, maybe Lewy body dementia. None of it felt certain.

I remember sitting with them in a neurologist’s office in April 2018, grasping for answers. Desperation gave me the courage to ask a question I had been holding back: “Could this be because he played football for so many years?” The doctor said she didn’t know. But she suggested something unexpected: “Steve, you’re special. When you pass, you should donate your brain to science so we can learn more.”

My dad smiled at the thought but by then, his mind was already slipping. I don’t think he fully understood. He was disappearing, bit by bit.

Football was his first love. Growing up in Seattle, he excelled in wrestling and football, eventually playing under John Elway’s father at Gray’s Harbor Junior College before transferring to the University of Utah. His career ended after a severe back injury, but his love for the game never wavered. He lived for hard tackles and big hits, especially as a fullback. Watching games together, I could see the pride in his eyes when players collided. It reminded him of his own glory days.

(Steve Wallace #31 Gray’s Harbor Junior College 1964)

But that love came at a cost. The hits he celebrated were likely the same ones that stole him from us.

Off the field, my dad built a life full of joy, hard work, and love. He was a police officer turned software sales executive, someone who could light up a room and make anyone feel included. He was always there for me. He came to every game and was present for every big milestone. He wasn’t perfect; his temper and perfectionism often loomed large. But he cared deeply about his family and those around him. I carry his empathy and determination with me every day.

By 2018, everything had changed. At my birthday gathering, he sat quietly, unable to follow conversations. I could see it in his eyes. He wanted to say something but couldn’t find the words. It was devastating. On a later visit in August of 2019, he didn’t recognize me. He lashed out and took a swing at me. He was confused and scared, as I pleaded with him to remember who I was. That moment broke something in me. The man who had always been my anchor was slipping away for good.

In December 2020, after many falls and fire department visits to the home, my mom made the heart-wrenching decision to move him into a memory care facility. By then, COVID had stolen what little time we had left together. When he passed in March 2021, I wasn’t there to say goodbye.

Amid the heartbreak, my mom and I worked to honor his final wish: donating his brain to science. The Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) stepped in when other organizations couldn’t, connecting us to the UNITE Brain Bank and Boston University’s groundbreaking CTE research team. Their guidance made the impossible feel manageable.

On March 8, 2021, I reached out to CLF’s founder Chris Nowinski via a LinkedIn message. To my amazement, he replied. By noon on March 9, all the arrangements were made. My dad passed away later that afternoon. Knowing that his death would help others brought us a measure of peace. I am forever grateful to Chris for the quick reply!

Eight months and two family interviews later, we received the results of his study. My dad’s brain showed advanced Alzheimer’s, Lewy body dementia, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This is the now well-known degenerative brain disease caused by repetitive head trauma. The diagnosis explained so much: his temper, depression, and cognitive decline. CTE wasn’t even a term we knew growing up, but it had shaped so much of his life, and ours.

CLF gave us answers and a purpose. They continue to lead the charge in understanding and preventing CTE. Their research has shown that just one year of tackle football before age 12 increases the risk of CTE by 30%. This is not just an NFL or college problem.

My dad understood the dangers, which is why he didn’t let me play until I was 14. I’m grateful for that decision. Today, I advocate for flag football as a safer alternative for kids. Tackle can wait.

My children, thankfully, have chosen different paths. My son has no interest in football and thrives in baseball and running cross country. My daughter plays soccer and though I worry about its physicality, recent rule changes such as banning headers for kids under 12 gives me hope. These changes are a direct result of CLF’s work.

As I watch my kids play sports, I often feel my dad’s absence. He would have been the loudest voice on the sidelines, beaming with pride. I take comfort in knowing that his legacy lives on. Not just in my family but in the critical research that will protect future athletes and their families from the devastation of CTE.

If our story resonates with you, I encourage you to think twice about enrolling your kids in contact sports. Talk to them about the risks and dangers we know about but continue to ignore or not give the attention it deserves.

CLF is doing lifesaving work, and I hope my dad’s story inspires others to support their mission. Together, we can honor the past while building a safer future in contact sports.

Fulton Walker

Before Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, Tim Tebow, or Kyler Murray blurred the lines between professional football and baseball, there was Fulton Walker. Walker grew up in Martinsburg, West Virginia and started playing tackle football at eight years old. He raced past defenders in youth football and shined on the baseball diamond. His exploits became the stuff of legend. Walker’s son Kevin was born when Fulton was in high school, so Kevin was well versed on his dad’s athletic prowess by the time he grew up.

“I was sitting in one of my P.E. classes and the teacher tells me how my dad was the best athlete to ever come out of West Virginia,” Kevin said. “He was saying, ‘I watched him play a baseball game one day and rob a home run and then that night run a punt back.’”

Walker was a four-sport letterman for Martinsburg High School and a key player at home as well. He would rush back home from games and track meets to mow his family’s yard and to split wood for a fire.

After he graduated from Martinsburg, the Pittsburgh Pirates selected Walker in the 25th round of the 1977 MLB Draft. He opted instead to attend West Virginia University, where he watched many football games as a kid and where he could play both football and baseball.

Walker became one of the first Black athletes to play for the WVU baseball team. In football, he played running back and returned punts for the Mountaineers as a freshman. He made headlines his first season by returning a punt 88 yards for a touchdown against Boston College.

He switched to defense his junior season and held a larger role on the team. Coach Don Nehlen arrived at WVU for Walker’s senior season and immediately counted Walker as one of his favorite players.

“You have certain guys on your football team that really enjoy the game – it doesn’t matter if it’s Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday or Saturday, they like to play and Fulton was one of those guys,” Nehlen would later say. “You’d go out there on Tuesday and he was grinning and then on Wednesday he was grinning. He was very popular on our football team.”

Walker’s popularity was not contained to the Mountaineers locker room. Kevin Walker saw his dad get stopped by friends and strangers his whole life. Fulton could not go to a cookout or a grocery store without someone wanting to stop and chat with the local legend.

“He was always pulled one way or another for conversation and one minute turned into 30 minutes and we’d be hours late for things. And he would always stop. He always had time,” Kevin said. “He’d never act like he was Superman. You know, he was just a regular old guy from a little country town.”

Walker’s senior season at WVU was a huge success. He finished with 86 tackles and two interceptions for the team in a season that would be credited with turning the football program around. The Miami Dolphins selected Walker in the 6th round of the 1981 NFL Draft.

His cool, upbeat, down-to-earth personality made him just as much of a locker room favorite in Miami as he was in Morgantown. Walker’s next-door neighbor in Miami was Dolphins star quarterback Dan Marino. Walker and Marino bonded over the rivalry between their alma maters, Walker’s West Virginia and Marino’s Pittsburgh, which is serendipitously known as “The Backyard Brawl.”

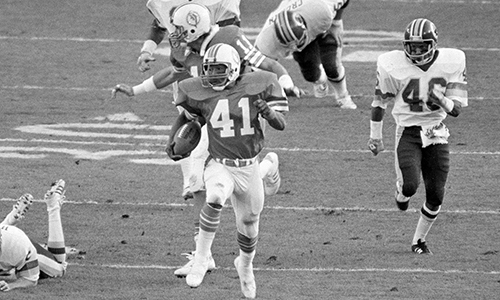

Walker played five seasons with the Dolphins as a cornerback and a special teams ace. His career highlight came when he became the first player to return a kickoff for a touchdown in a Super Bowl when he sprinted 98 yards for a touchdown to give the Dolphins a 17-10 lead in Super Bowl XVII in 1983.

No one could catch Fulton Walker that day, or most days for that matter. But Kevin did. Once.

“We were walking to my aunt’s house and he was like, ‘Man you wanna race?’ and I said let’s do it,” Kevin said. “And we ran pole to pole and I beat him.”

Walker tried to put an asterisk on the defeat by claiming he did not have the right footwear for the occasion. But 13-year-old Kevin let everyone in his junior league baseball dugout know he beat the Super Bowl record-holder.

After two more injury-riddled seasons with the Los Angeles Raiders, Fulton Walker retired from football in 1986. Playing primarily special teams, Walker only saw the field for a handful of plays each game. But the impacts he was involved in on kick and punt returns count among the fastest and most violent in the sport. After football, Walker had his ankles fused, his vertebrae fused, and took more than a dozen pills a day to alleviate pain in his neck and to help him sleep.

“His injuries, you’d think it was from motorcycle wrecks or something. But he just played football. So yeah, you’re tough. But your body can only take so much,” Kevin said.

With football behind him, Walker went back to WVU to earn his master’s degree in Industrial Safety. Kevin says Walker was extremely sharp and could handle a very large workload. For years he managed a trucking company in West Virginia and then became a teacher and coached football and baseball back at Martinsburg High. He satisfied his itch to stay physically active by playing golf and softball as often as he could.

Walker then started to struggle with his memory. He would forget where he put his keys, leave his car running, go to the store and forget why he went by the time he got there, and repeat himself in conversations. These short-term memory issues affected his ability to work. He would forget how to use certain computer systems he mastered the week before. Eventually, the state of West Virginia determined he needed to go on full disability.

The memory battles caused Walker to get frustrated with himself. He took his frustrations out on others and slipped into depression.

“My problem is I can’t multi-task. I can’t get my brain full of stuff because it puts me in a place of confusion,” Walker said in an interview with Katherine Cobb in September 2016. “Stuff in the present I can have problems with, but stuff in the past, I still have good recollection. I have to write things down now, so I remember. It is what we guys have been going through but we didn’t understand what was going on. It’s been frustrating and overwhelming sometimes.”

When Kevin saw his dad almost daily, his decline was less noticeable. But when he moved away to North Carolina and saw his dad less frequently he noticed how steep his fall was. Kevin knew his dad needed help and set up appointments for neurological testing in Orlando and Atlanta. Those tests showed Walker suffered from dementia, which qualified him for benefits from the NFL’s “88 Plan,” named after Hall of Fame tight end and CLF Legacy Donor John Mackey.

On the night of October 11, 2016, Kevin called his dad to let him know he would need to switch cars with him for Kevin’s upcoming work trip. Kevin arrived the next morning and grabbed the keys his dad had left out on the counter. He chose to let his dad sleep rather than to say goodbye. As Kevin was driving home from the meeting later that day, he received a call that Fulton was being rushed to the hospital.

Kevin drove to meet his dad at the hospital, but it was too late. Fulton Walker was pronounced dead on October 12, 2016 at 58 years old. He died from a heart attack.

Walker’s funeral in Martinsburg was full of testaments to his humility, generosity, and ability to make those around him feel like they, not him, were the Super Bowl record holder in a conversation.

Kevin and the family decided to donate his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank after his death to see if his cognitive and emotional problems could be attributed to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, diagnosed Walker with mild CTE in his dorsolateral frontal and temporal cortices.

Fulton Walker loved football too much for the family to hold ill will against the sport for its role in his CTE. Instead, Kevin believes his dad would have opted to play flag football as a kid and would advocate for the next generation to do so as well. Kevin points to Barry Sanders’ training in flag football to increase his elusiveness to show how playing flag football improves ballcarriers’ open-field skills.

Kevin knows that playing pro football when his father did and now are two different financial realities. He thinks today’s NFL players have the liberty of shortening their careers and protecting themselves in a way his father’s generation did not.

To other children who have parents that spent a life in contact sports and who might be at risk for CTE, Kevin urges you to stay aware, and take action to get help sooner than later if you see signs like mood swings or forgetfulness.

Kevin will always remember his dad for his work-ethic, humility, laid-back personality, and as a pioneer for two sport athletes.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms or possible Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.