I am so grateful to the Concussion Legacy Foundation for this opportunity to share and honor Pat’s life in the Donor Gallery. It is so important to be able to communicate with an audience who understands, believes, and can empathize with the pain of the effects of CTE for all involved. One of the greatest challenges in addition to the pain, as I am sure others can attest to, is having those around you not understand and believe the disease and refuse to be educated about it. They judge your loved one about their bizarre and often damaging behaviors. The person you once knew is no longer there, and misunderstandings, isolation, and judgement abound. The amazing work of the wonderful researchers, doctors, and team members at Boston University, the Concussion Legacy Foundation, and the VA are not only helping prevent future generations from this debilitating disease, but provides comfort and understanding for those family members and friends left behind.

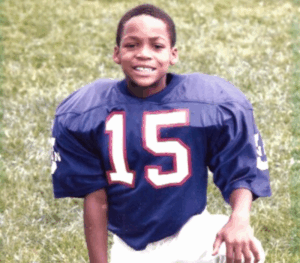

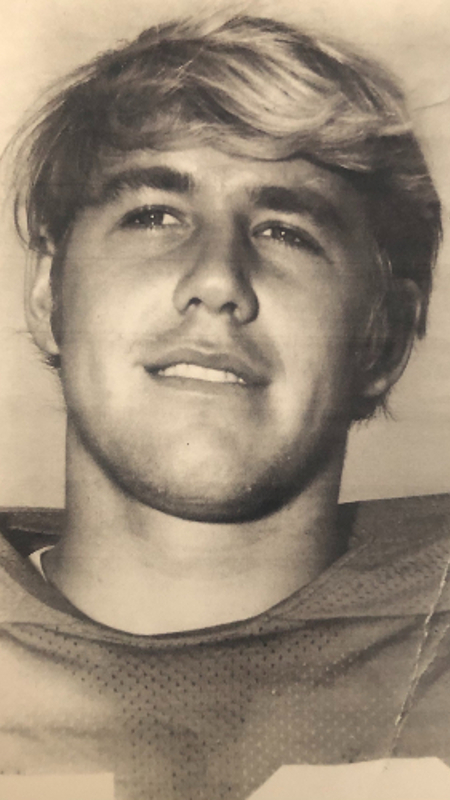

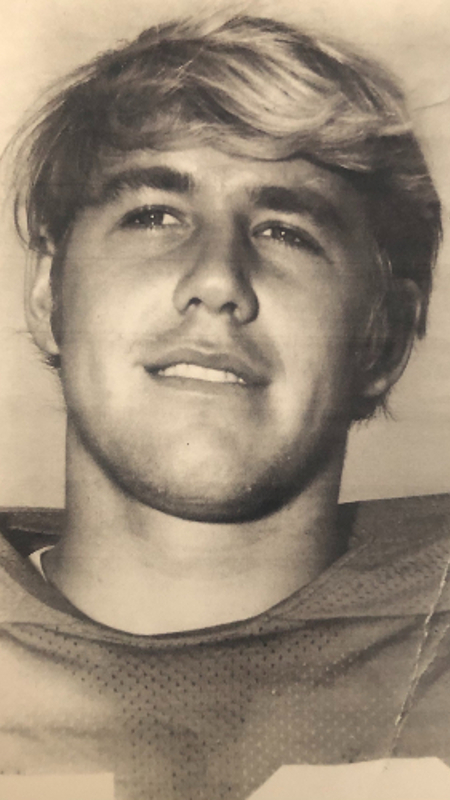

My husband “Pat” was one of six children, born fourth in line, to a loving, hardworking Irish Catholic family in Peoria, Illinois. Pat, who had always been athletic, outgoing, smart, but somewhat of a rebel was perfect for competitive sports. At a young age, according to his siblings, Pat was always on the go, playing neighborhood baseball, memorizing stats, and combing over the newspaper sports’ pages. One of his favorite memories was attending a Chicago White Sox game with his dad. The tickets and trip which they could not have been able to afford was given to Pat by a scout who was impressed by Pat’s knowledge of the games and players he was observing just one afternoon on the bleachers – Pat was ten years old. Pat’s dad nurtured his love of sports and the comradery Pat experienced at his grade school through high school teams were irreplaceable and lasted throughout his lifetime. He loved his teammates and the game of football. His high school teammates from his undefeated Spalding High School team were his best and most loyal friends until Pat passed away in 2019. His high school football success gave Pat the opportunity to be the first in his family to graduate from college when he received a scholarship to the University of Wyoming.

His junior year, Pat transferred to Illinois State University where we literally met on the Redbird football field. I was a cheerleader and he whispered to one of his teammates, “I am going to marry that girl.” He did! He had caught my eye as well, and two years later we were married.

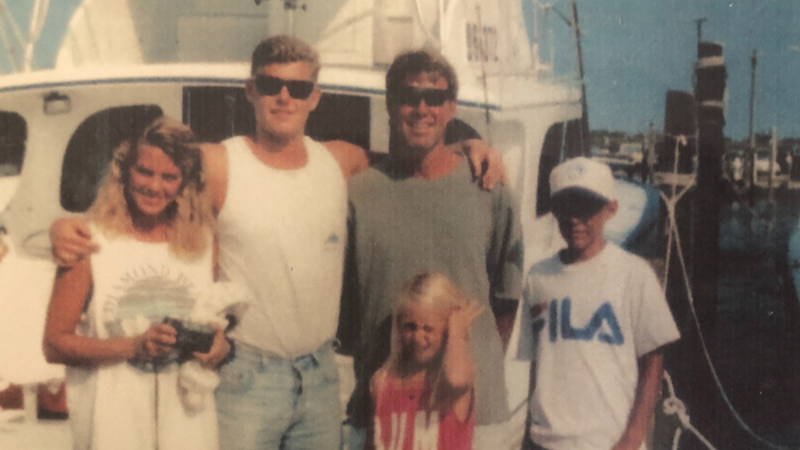

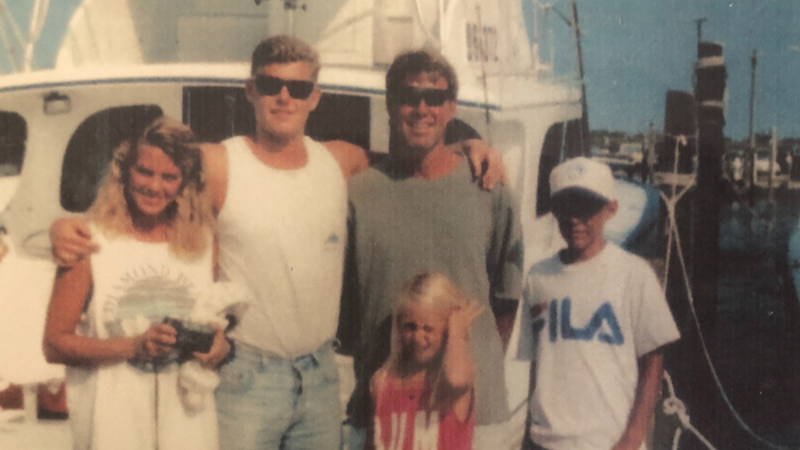

Thus began our life in Peoria, Illinois. After graduation from ISU, I became a special education teacher. Pat worked a couple of jobs until he found his niche as a State Farm Insurance Agent. Pat loved serving people and meeting their needs. He built his business from the ground up. I still remember him making cold calls on a little card table set up in our basement. Pat loved people and his outgoing, fun-loving personality served him well in this occupation and he became a successful State Farm Agent. For 30 years, he was able to provide a generous and beautiful life for our three children and me. Pat was a wonderful family man and was so supportive of everything our three, very active children did. He loved coaching Little League for the boys for years, and I don’t think he ever missed a game throughout their high school years or any of our daughter’s dance performance. Pat loved God and his family. He was active at church for many years and always put his wife and children first. He was very selfless about doing things for himself but took good care of his body by playing softball, running, exercising, and occasionally golfing with his fellow insurance agents. He provided us with lovely vacations at the beach, which he loved. Pat also loved music and writing and shared that appreciation with our children. I am so grateful for the beautiful life Pat gave me and my children for the first 50 years of his life.

The Challenging Years

I recall it was around Pat’s 50th birthday, and ironically we were going to Pat’s high school football team’s induction into the Peoria Hall of Fame. Pat had been instrumental in nominating them and it was then I noticed he started experiencing bouts of paranoia. His anxiety was off the charts and he would obsess about everything. At one point, at his mother’s funeral he overdosed on Xanax, a prescription he had been given for 20 years prior, unbeknownst to me. Finally, after a bizarre and grizzly suicide attempt in our home where he had hallucinated and ended up in a psychiatric hospital ward. Thus began the downward spiral of the next 19 years.

I am not sure if I can justly describe all the numerous events that occurred with Pat in those last 19 years before his death at age 69. I just know they were extremely painful, stressful, and debilitating to Pat, our children and their families, our loyal friends, and me, who chose to stay involved. Pat was in and out of psychiatric hospitals with diagnoses from temporal lobe seizures, to schizoaffective disorder, to bipolar mania and everything in between, including alcoholism. He was also an inpatient at several addiction centers and nothing seemed to help. He had trouble doing the cognitive work involved in the treatment programs. I tried everything to get him help, and at one point a loyal friend and I flew him to Houston to admit him to an inpatient psychiatric hospital. There, while under the 24-hour care of doctors and nurses, he lit himself on fire. He then spent several months in the hospital burn unit in Houston where another doctor suspected temporal lobe seizures. Upon return to Illinois, I took Pat to Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for further testing. No seizures were detected but the neuropsychiatrist could see that his frontal lobe was deteriorating and frontotemporal dementia was suspected. Upon our return to Illinois, Pat’s behavior continued to wax and wane. Sometimes, frightened for my life, I called the police and the emergency response service. I am forever grateful for one response team member named Dan who spent many hours at our home calming Pat down, easing my fears and educating me about mental illness. Dan often accompanied Pat to psychiatric facilities in our area if the local unit was full. I look back at many “angels”, such as Dan, who I could not have made it through the last 19 years without.

Pat continued to decline cognitively, and his anxiety was out of control. During this time after his staff (more angels) and I tried to help his insurance business stay afloat, we finally closed his agency. I attended support groups wherever I could, including NAMI, Al-Anon, AA, and FTD, but nothing seemed to entirely fit. I had difficulty finding anyone that seemed to be able to identify with what our family was going through and for the length of time it had been going on.

Pat’s cognitive abilities continued to decline and while I was away at work he started ordering everything in sight from catalogs that came to our home. He even bought a home in Florida, sight unseen. He would become very argumentative if I tried to talk to him. I talked to doctors and lawyers about his mental state, and was discouraged to try and gain legal guardianship to take over his finances. His behavior would be okay for a while and at one point went on a lovely day fishing trip with his granddaughter and friends. On the way home, they were hit from behind by a drunk driver going 90 MPH. They were all treated and released form the ER, but Pat sustained fractures in his hands and back and was told to go to pain clinics. He became addicted to opioids quickly and began drinking in between. At one point, we got an emergency call from his internist that his PSA was sky high and he had prostate cancer. Shortly after a call from his doctor that an x-ray revealed both of his hips were bone-on-bone and needed replacement. In 2012, Pat endured 42 radiation treatments for cancer, and two hip replacements. He was tough! He was hospitalized so much at that point that I was able to realize that he had depleted most of our savings. Pat continued on prescribed opioids and by this time they had taken over.

After completing the radiation and recovering from surgeries, Pat took off to Florida. Who knows what happened there. He finally ended up in a hospital there and his loyal friends (more angels) brought him back home. We sold our home tin Illinois and moved to Chicago to be closer to my daughter, who had been an amazing support. Because of her medical training as a PT who had worked with patients with brain injuries, she was more understanding and better equipped to deal with her father’s behaviors despite the terrible toll they took on her. During our residency in Chicago, we went to Northwestern for Pat’s medical needs, and it was there that the neuro department suspected Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). He had shared with them about the numerous hits he received in football practices and often being knocked out and “seeing stars”. For a time, he saw a psychiatrist who treated his bipolar mania but Pat often resisted treatment. Twice, Pat was taken to the ER, only to be released the next morning by a failed system and communication.

Pat became aware of the liberal cannabis laws in Illinois and received an easy OK from a local clinic because of his previous prostate cancer. The clinic was within walking distance of our apartment. Illinois allowed for $2500 worth of marijuana a month, and believe me Pat used every bit of it! Although the medical marijuana “sidewalk stores” were secure and regulated, there was no regulation on THC levels. Of course, Pat chose and was legally able to use one with the highest THC. His behaviors became out of control. After speaking with a representative (another angel), she instructed me on how to get his license to obtain medical marijuana revoked. But I had to have a safety plan in place because she feared for my life if he went to get the marijuana and couldn’t. The opportunity came when I drove Pat to another ER in our hometown at his request. I left him there and he became hospitalized. After several weeks, a physician organized a placement at a nursing home in Florida, which Pat agreed to. This ended in his removal from the facility and more months of me trying to find him and manage his care. At one point, I felt my only option was to divorce him to protect what assets we had left. But somehow he became so ill and through the help of many wonderful lawyers and bankers, I was able to manage our finances and get control.

He finally ended up back in an assisted living facility in Florida where his behavior was relatively managed. I moved there temporarily and accompanied Pat on all doctor appointments. Though he was still addicted to opioids, at least they were controlled by nurses at the facility. We then discovered Pat had lung cancer. Because of Pat’s limited cognitive ability, his mania, and still having legal rights, he refused treatment in the early stages. By the time I got him moved to South Carolina, where my daughter and family now reside, he was having additional urinary tract problems and spent many months in the hospital. Finally, some health issues were resolved and I was able to move us into an assistive living facility to help care for him. Although cancer treatment was tried, it was too late. Pat passed away in a hospice facility on September 26, 2019.

I am so grateful for the last two years we had together! Though every day was difficult, Pat’s behavior became more stable and he was able to heal many relationships with his children, extended family, and friends. I am so grateful for those who showed Pat unbelievable unconditional love and forgiveness during this time. They remembered the wonderful Pat they once knew and were so supportive of us both. I am especially grateful for my children and their families for their daily support. Pat was able to spend many wonderful moments with our daughter, her husband and new little grandson. My sons and their families traveled from Arizona to be with him, and many more beautiful memories were made. What started as a tragic story ended in love and forgiveness. The friends we met at the assisted living facility and the staff who cared for him were life-changing and eternal to me, as well as my church family.

I do not share these events to dishonor my family – quite the contrary. My husband was a wonderful man before his illness manifested itself. My hope in sharing our story is to make others more aware of how brain trauma can affect so many; not only the individual, but their families, friends, physicians, and caregivers. New developments in sport safety are happening, but we need everyone’s help. I also hope this story will help people not to ever judge. One never knows what someone else is going through.

Be kind. Be compassionate. Educate yourself.