Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Every few months, Brenda Boose receives another adoring message about her late ex-husband, former NFL player and Washington State University star Dorian Boose. They pour in from strangers, old teammates, friends, and even people who only met Dorian once. Brenda printed out a particular message she received from a young man in 2021. The note reminded her about Dorian’s generosity and the effect he had on others:

I met Dorian in the fall of 1997 when I was 16 and a junior in high school. A friend of my family was a big booster for the Cougars and he invited me to join the team for an away game at USC. Most of the players were too busy but that changed when my dad had me approach Dorian. He was incredibly friendly and took me around, introducing me to everyone. After the game, we snapped a few pictures and exchanged information.

Some point later, Dorian reached out to me and we got to chat like old buddies. I remember I had told him I loved to sing, and we even sang together on the phone. After the Rose Bowl, he sent me his practice jersey and WSU warmup suit. Though our correspondence ended as the years passed, I still remember Dorian fondly and bring up him up whenever I get the chance.

“That’s just the kind of person Dorian was,” said Brenda.

Coming together through faith

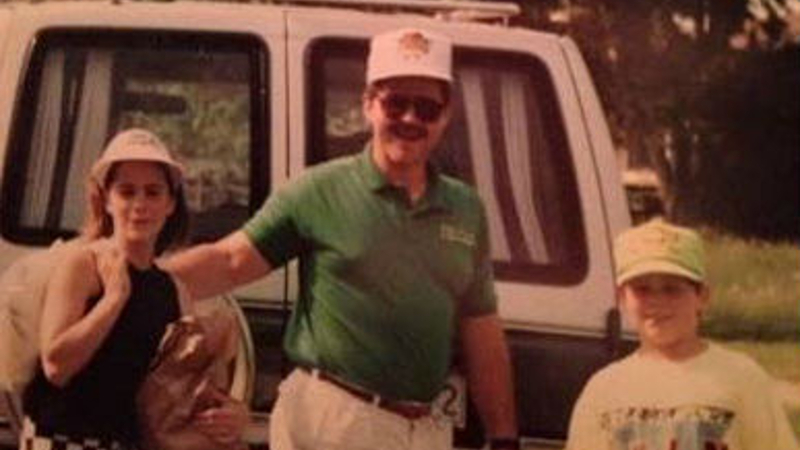

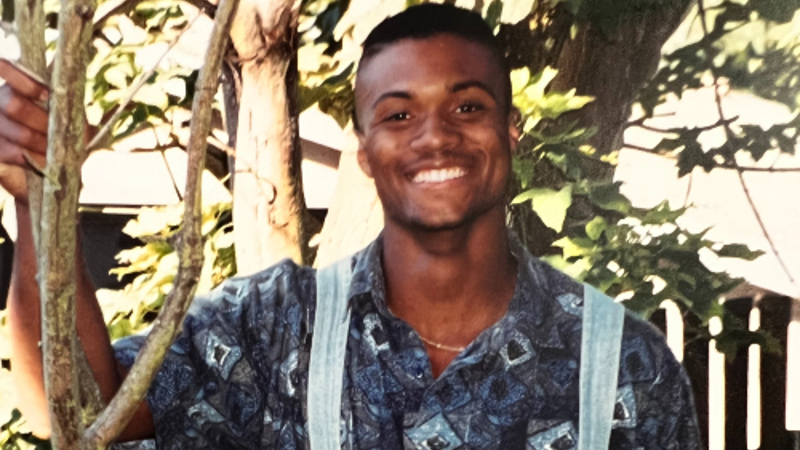

When Brenda first met Dorian in 1991, he was attending Walla Walla Community College in eastern Washington. Dorian and Brenda were members of the local church choir. In addition to sharing the same faith, she was drawn to his gregarious personality and kind heart.

“Dorian had a natural joy that drew everyone in,” said Brenda.

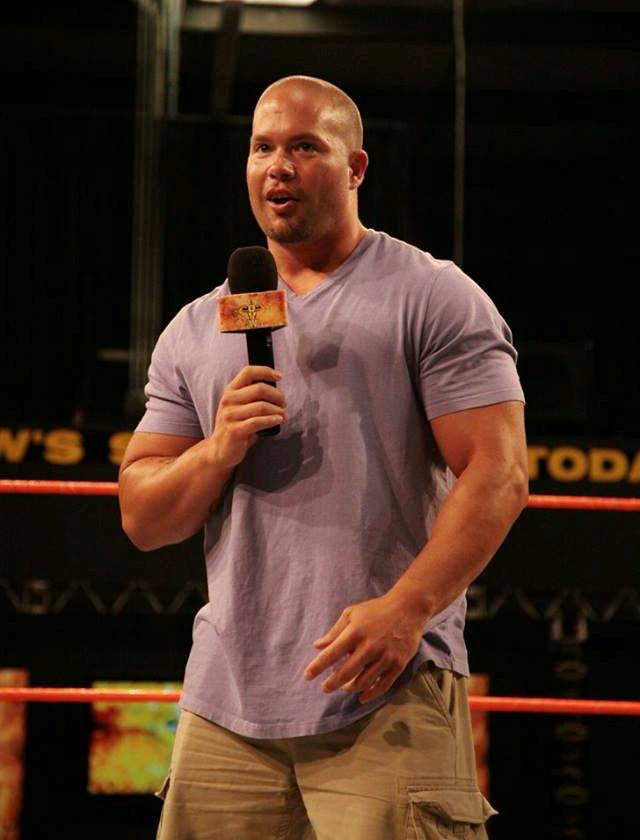

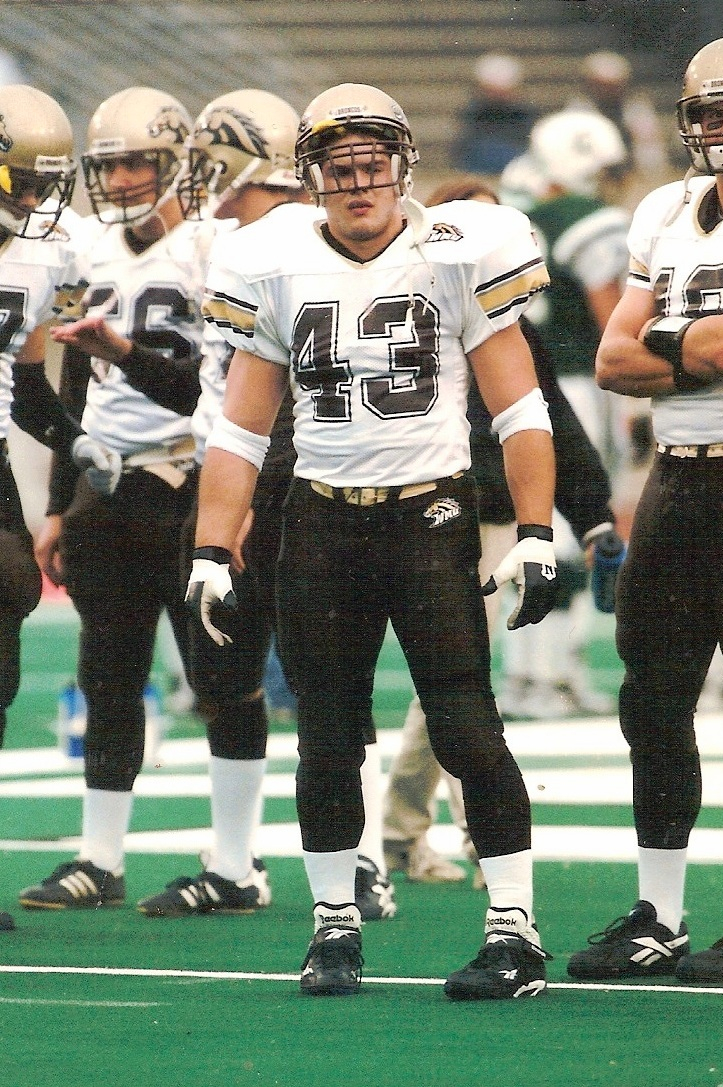

Certain talents came naturally to Dorian. He could sing very well and learned how to play piano completely by ear. Dorian was extremely athletic and at 6’6,” loved to play basketball. He picked up tackle football for the first time as a freshman at Foss High School in Tacoma, Washington. His combination of size and speed immediately turned heads and led him to Walla Walla CC and eventually to a scholarship to play defensive end for the Washington State Cougars.

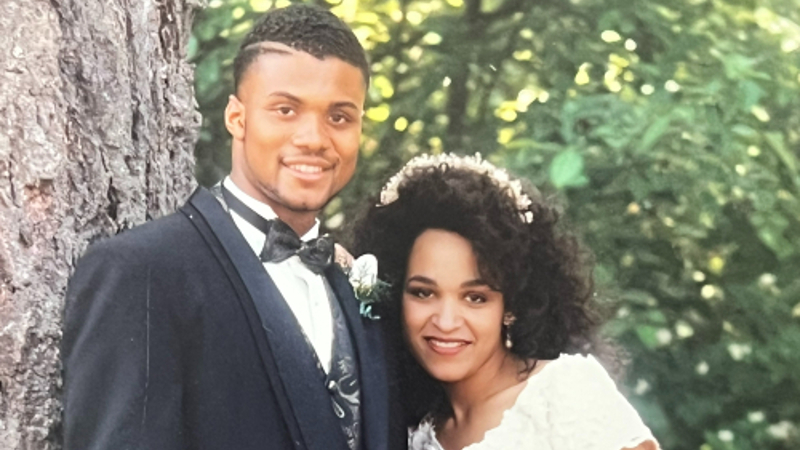

Dorian and Brenda started dating in 1992 and married in 1995 while Dorian was at WSU. Having each grown up in strict households, the couple shied away from drugs and alcohol. Brenda recalls how silly she and Dorian felt when they were served champagne during their honeymoon. Family and faith were the bedrock of their marriage.

High hopes

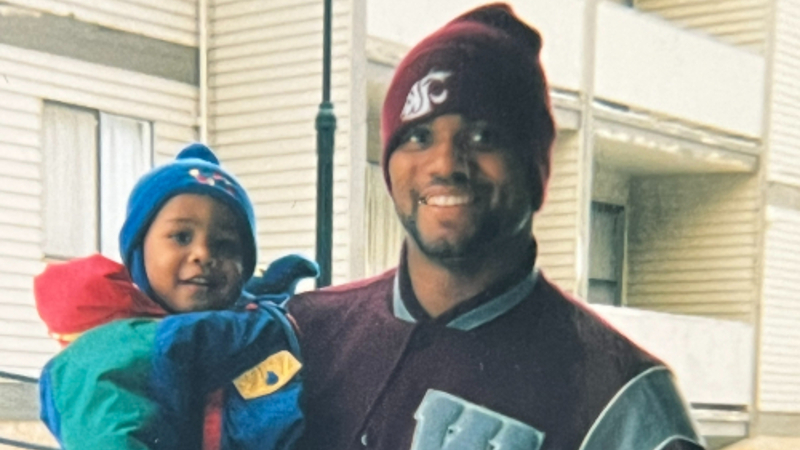

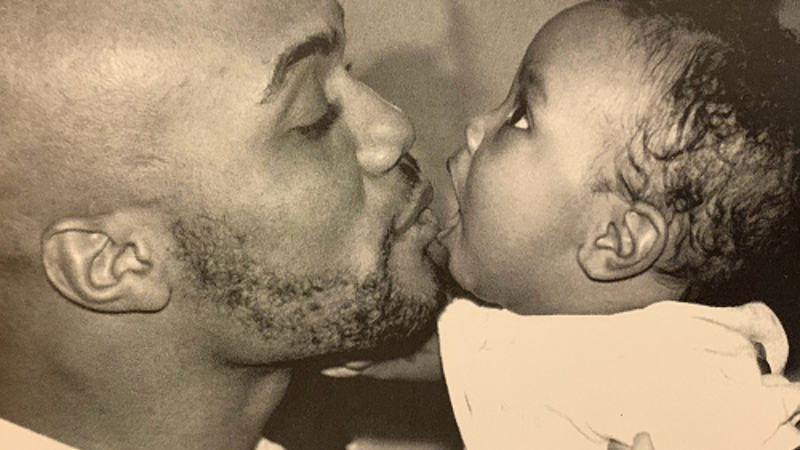

Brenda and Dorian’s first son, Taylor, was born in 1996. Brenda remembers Taylor’s early years fondly for how much Dorian embraced being a father. Dorian loved his family immensely and could often be found horsing around and playing with Taylor.

Dorian balanced fatherhood and athletics well. He played a major role in putting Washington State University’s football program on the map with the “season of destiny” in 1997. The Cougars went 10-2 and made it to their first Rose Bowl appearance in 67 years. Dorian’s teammates voted him defensive captain for his outstanding play and leadership.

Dorian’s breakthrough in 1997 created the possibility of a bright new future. At the NFL Combine before the draft, Dorian was told he could have a 15-year football career. The New York Jets saw his potential and selected him 56th overall in the 1998 NFL Draft. An overnight star in New York, Dorian spoke for hours with everyone from then-Jets coach Bill Parcells to Regis Philbin and Kathie Lee Gifford for an appearance on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee.

“We were extremely excited about the future and for what was ahead,” said Brenda. “We thought we would be together forever and raise our boys and live a very fulfilling life.”

A different Dorian

Dorian’s time with the Jets didn’t live up to expectations. Injuries made it difficult for him to get consistent playing time. After two years in New York, he joined the Washington Commanders for another injury-riddled stint. Eventually, he signed with the Houston Texans but was waived again after a knee injury.

Brenda gave birth to the couple’s second son, Brady, in 2000. Within two weeks of getting cut by Houston, Brady was diagnosed with autism. For the Boose family, the already anxious stretch of Dorian’s career became even more stressful and overwhelming.

Around then, Brenda noticed a slightly different Dorian. Rather than embracing the challenge of Brady’s diagnosis, he became distant and aloof, developed a careless attitude, and was disappearing on his own for many evenings. When Brenda pressed him on what he was doing those nights, Dorian told her he had been drag racing.

“I was just shocked,” said Brenda. “It was so out of character for him, and I couldn’t make any sense of the situation.”

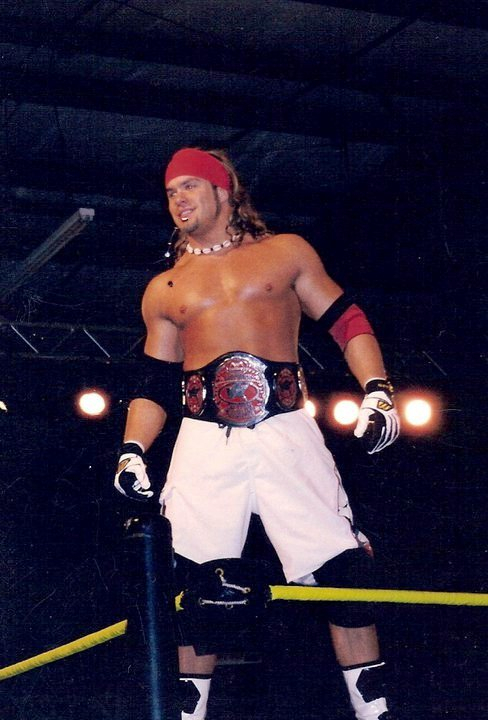

When he was healthy again, Dorian decided to try to rejuvenate his football career in the Canadian Football League. His career in the CFL couldn’t have started any better – he made seven sacks and won the Grey Cup his first year with Edmonton in 2003.

Dorian’s marriage was still strained and his residence in a different country only exacerbated the issue. When Dorian did call home, Brenda could hardly recognize the person on the other line and was heartbroken by how much he had deprioritized his family.

“It was like, ‘Who am I talking to?’” said Brenda. “The whole thing just fell apart.”

Exhausted from the uncertainty of their relationship and needing to provide stability for Taylor and Brady, Brenda made the difficult decision to file for divorce in 2003. Dorian played just one more season in the CFL in 2004 before retiring from professional football.

For the next decade, Brenda’s contact with Dorian was at best inconsistent and mostly non-existent. Brenda tried to protect the boys’ emotions as much as possible and didn’t want them to hear from Dorian if his communication was going to be scattered and incoherent. Because of the distance between them, they were mostly in the dark about where Dorian was and what he was doing.

Around 2015, Dorian’s acquaintances began messaging Brenda to tell her he needed serious help. Brenda reached out to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and was able to connect with a detective who would investigate his whereabouts. He found Dorian and let Brenda know her ex-husband was living on the streets of Edmonton. The officer also told Brenda how well-loved Dorian was in the unhoused community. Later, Brenda learned Dorian prayed and served as encouragement for others in the community.

Despite the pain of learning that Dorian was living on the streets and the frustration and confusion of the past decade, Brenda was comforted to know his core values of faith and generosity were still on display. She passed along a message for the officer to tell Dorian to contact his parents and that God loved him. The officer relayed the messages and told Brenda they moved Dorian to tears.

In 2016, after years of distance, Taylor wanted to reach out to his dad and wish him well. With the help of Dorian’s mother, the family got in touch with Dorian, who was in a shelter getting help. Taylor and his father were able to have a conversation over the phone that spring.

A few months later, Brenda was awakened by a phone call the night of November 22. Dorian had died by suicide. He was 42 years old.

Brenda is thankful her family was able to speak with Dorian before he passed away.

“It was nothing but God that made that moment happen and we are grateful to this day,” she said.

Brenda doesn’t remember Dorian ever discussing concussions while they were together, and they had separated years before CTE had ever been diagnosed in a former NFL player. But after discussions with Dorian’s former agent, Brenda decided to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. There, Dr. Ann McKee diagnosed Dorian with stage 3 (of 4) CTE. Dr. McKee told Brenda how Dorian had one of the most severe cases she had seen in someone his age.

Brenda had two reactions to the diagnosis: first relief, then grief.

The relief came when Dr. McKee suggested the severity of Dorian’s CTE could have caused his behavior to change quite early in his life. The pathology explained why Dorian’s actions and behavior were so drastically different from the man Brenda knew Dorian to be.

Then came the immense grief. Brenda struggled to eat and sleep as she thought about how much Dorian would have suffered by himself without understanding exactly why he was changing.

“The CTE took Dorian’s life,” said Brenda. “It took his future. It took his being a husband. It took his being a father. It took everything.”

Redemption

Brenda wants to share Dorian’s story to show why he struggled near the end of his life and to dispel the notion that his lack of NFL success drove him to despair.

“Dorian wasn’t bitter about his career not panning out,” said Brenda. “There was so much more to him than football. CTE caused this.”

These days, Brenda still has many beautiful memories about Dorian’s time in football, but her family’s relationship with the sport has changed since the diagnosis. With the knowledge she has gained through this experience, Brenda is now a strong believer in Flag Football Under 14. Even through Dorian didn’t start tackle football until high school, she sees moving away from youth tackle football as the best way to prevent future cases of CTE. Brenda urges parents to have the conversation about flag football early on for the health and safety of their kids.

Brenda is grateful for how much more information there is about CTE than there was when she and Dorian were married. If anyone finds themselves in a situation like she was in the early 2000s, she recommends leaning in on the resources available on CLF’s website and elsewhere. For other partners of suspected CTE, she has three pieces of advice: get educated about the disease, reach out for support, and have as much compassion as you can.

Though Dorian passed away far too soon and left her life well before his death, Brenda can see how the best of Dorian lives on in her two sons. In Taylor, Brenda can see Dorian’s many talents and strengths. And in Brady, Brenda sees glimpses that remind her of the beautiful man she met in the church choir all those years ago.

“He has his father’s spirit, always with a smile on his face and a joyful presence,” said Brenda. “I just want everyone to remember that part of Dorian more than anything.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at 988lifeline.org/chat

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.