McKenna Brown

Andrew Carroll

Richard Clasby

Leo Collins

Danny DiFrancesco

Danny was the second of five children. By nature, he was quiet and shy. Sports helped draw him out, and he grew to have many friends. He loved animals, nature, and adventure. His sensitivity showed very early; I remember he was sitting in front of the TV intently watching Sleeping Beauty with the family milling around him on a New Year’s Eve. He was less than three years old. As I started to move him a little farther away from the screen, I noticed his eyes were welled up with tears – just as the prince was waking the beauty. He never lost that sensitivity and became the most compassionate human being.

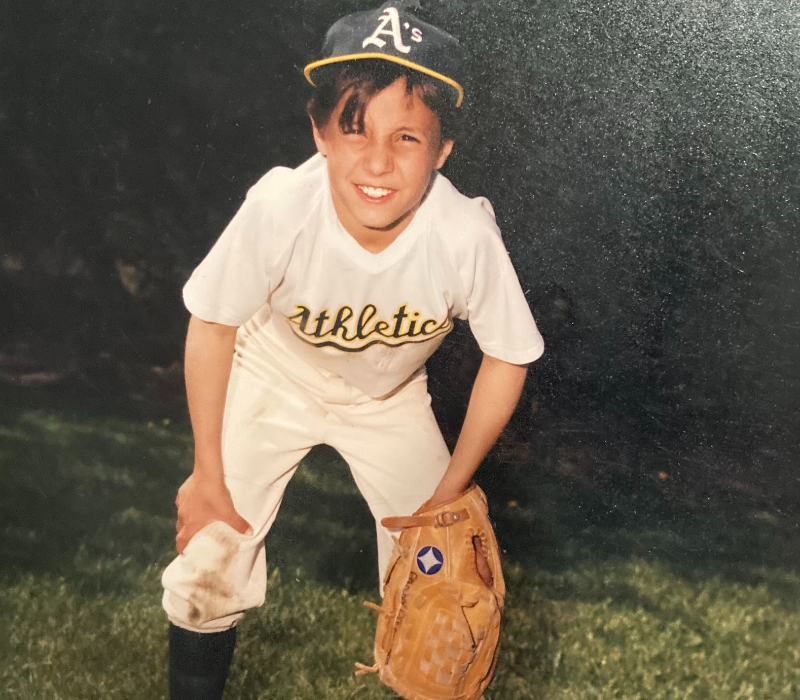

Danny’s first years of school were rough. He had debilitating separation anxiety that caused a sense he was different from others – a feeling he was acutely aware of throughout his short life. When Danny was around nine years old, he suffered his first concussion playing baseball. The protocol then was fairly simplistic: watch for headaches or uneven pupil dilation, and make sure he could be awakened from sleeping. At the age of fourteen Danny was hit by and pinned under a truck while riding his bike. This was his second documented concussion, which also left him with a fractured lumbar spine.

Within two years of the bike accident, we were noticing impulsiveness, outbursts, indecisiveness, and frustration. After punching a window and severing his artery, Danny’s behavior and judgment were being called into question. ADD and PTSD from childhood trauma were the first of many diagnoses. He initially rejected counseling, medication, and labels, furthering his confusion while compounding his anger and reactiveness. His passion for sports, in particular hockey, was his primary outlet. His ethics in sport and hard work never wavered, even though his personal life began to unravel. Our separation and divorce sealed the deal, and soon he found himself in legal trouble and suspended from school. He played harder in hockey than ever and sustained more head injuries. By the time he was 27, Danny felt he had to get as far away from our town and its memories as possible. The next few years seemed to be the best for him. He found and loved South Lake Tahoe. Within a year he worked his way into a supervisory position as security in a casino; he would say he was good at this job because he knew how to relate to the ‘troublemakers’ and effectively deescalate any bad situations. He made fast and close friends with others who loved to snowboard, hike, and fish with him. There were hints of troubles – heartbreaking relationships or annoying roommates, but it all took a turn when Danny’s best friend had to carry him off a ski slope after he tore everything there was to tear in his knee. He had to come home, and his athletic days were all but over.

The last ten years of Danny’s life were a cascade of insensitive or incompetent doctors, never knowing exactly which fire needed to be addressed first. His body and mind were simultaneously torturing him. He saw over two dozen specialists for almost every system in his body. He was hospitalized almost as many times with infections, injuries, disorders, and by then, reactions to dozens of ineffective medications or treatments. The ever-changing diagnoses from mental health providers were overwhelming. He was screaming in his sleep from night terrors. He couldn’t sleep, changed jobs frequently to accommodate his hurting body, and faced evictions due to either financial stress, “noise offenses” when sleeping, or both. Meaningful relationships were tested, leaving some broken. In the last few years, the only people he saw daily were myself, his lifelong friend and brother-in-law, T, or a health provider of some sort. I personally do not know what I would have done without T, Uncle J, or Danny’s friend, J. I don’t know, either, how much more painful it would have been if he hadn’t had their faith in him. And everyone who knew Danny would agree that without his niece, nephews, and little twin cousins to look forward to seeing, his life may have been void of any joy at all. He was keenly aware that family, friends, and the public at large saw him primarily as having troubles due to drinking. With complex PTSD and ever-worsening diagnoses plaguing his life, and the added shame of judgment and criticism, burns and cuts on his arm from self-mutilations were common signs of his internal and external pain. His desperate words, “There’s something wrong with my head,” and “Please, ma, please let me go,” or “Why am I like this” still echo in my head and absolutely break my heart.

Danny never stopped trying to find help, but he had lost hope. He became suicidal and made multiple attempts, even jumping out of my moving car. He was often triggered by the sight of a cop car, a knock on his door, or even thinking about another invasive or intrusive doctor appointment. A year or so before his death we had both watched a documentary about CTE, and Danny brought the subject up with his psychiatrist via Zoom. I happened to be on the call as well when this extraordinary man responded very compassionately and firmly. Dr. G had been reviewing the past two years of notes (he was relatively new) and asked Danny if his neurologist had done any brain scans or studies. The neurologist had ordered an MRI years earlier at my request, but said the results were unremarkable. The psychiatrist then asked Danny why it appeared that his primary was not treating his hypothyroidism. Or his anemia. Or his high cholesterol and blood pressure. Only one other specialist – his orthopedic surgeon – had ever approached Danny with simple human compassion and concern. The psychiatrist’s next comment was directed to me: Find him new, reputable doctors immediately, and get his brain looked at again. We did manage to get his brain looked at, but only after he had died suddenly. After 10 months we still have no answers from the medical examiner, or even an investigation into his death by local police. He had said many times that he just wanted to donate his organs to help kids. My daughter (almost by divine intervention) remembered to relay Danny’s wishes to the coroner. It was too late to harvest any organs, so she immediately pulled up the website for the Boston University CTE Center. This he could do. This is how we came to learn he had stage 2 CTE; bittersweet to finally have a diagnosis that explained so much and felt like vindication for him, but also unleashed a tidal wave of guilt and regret on family and friends who loved him so much.

There is an indescribable tragic cycle that starts with a head injury. The cycle of alcohol, or abuse, or judgment, or shattered families and relationships. The cycle of being misinformed and misunderstood. This is a horrifying and tremendously sad story. But Danny’s life absolutely had purpose. His life left us with endless and indelible joyful memories. He was a skillful and determined Easter egg hunter and there was no theme, costume, or competition he was too proud to embrace. He was known to scan the fridge and cupboards for so long thinking about what to eat, that inevitably he would walk away empty-handed mumbling, “I’m full.” He was a master at moving furniture – the bigger the couch and steeper the stairwell, the better. He always loved a good puzzle.

Our Danny was more than a good person. He was the one who never hesitated to help others or recognize someone else’s distress. He befriended and shared his food with local homeless people. Being judgmental of others was not in his nature; he was charming and could genuinely connect with anyone. He helped anyone stuck in the snow. He helped before you even knew you needed help. Despite his chronic pain he was the first one on the floor to pet an animal or play with a child. Despite his emotional pain he would take great joy from sitting at the kids’ table. He was colorful and quick with a laugh; smart, hilarious, clever, observant, and kind. He has opened so many hearts and minds to new insights on love, patience, and acceptance. His brain donation has helped educate and inform our family and community. I’m so sorry we can’t tell him how devastating his death will forever be. How painfully aware we are that we let him down. How enormous the hole is in our hearts he left behind. How much we love you, Danny.

You never seemed to understand why I was, and still am so proud of you. You are a warrior, and I celebrate your life and Legacy, and especially your strength and spirit. I will always love you. ~Ma

Reggie Fleming

Brian Fronczek

Todd Gillingham

Todd Gillingham had a quirky smile and a twinkle in his eye. He was the guy who lit up a room when he walked in. Todd was the life of a party and knew how to live each day to its fullest.

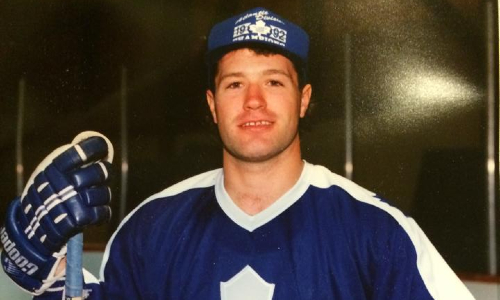

Growing up in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, Canada, Todd spent the summers of his youth on the baseball field, with cleats and bats giving way to skates and sticks during the winter months. He excelled at both sports but eventually turned his full attention to hockey, which he started playing around four years old. He was always the biggest guy on most teams, so expectations for him to excel were always high. But no problem for Todd — he surpassed them and much more.

Though Todd was big and could throw a hit, he would often give a shoutout to the smaller players prior to checking them. That’s the kind of guy he was. His dedication to hockey paid off at the age of 16, when he joined the Verdun Junior Canadiens of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL).

Despite moving from his small Newfoundland home community (population 20,000) to a largely French-speaking suburb on the outskirts of Montreal, Todd immersed himself in the culture and taught himself French. This wasn’t surprising to those who knew him. Todd’s level of intelligence can be best exemplified during his senior year in high school, while still playing hockey in Quebec, when he returned home with six weeks left in the school year. His goal was to write his final exams and graduate with all the kids he grew up with. Mission accomplished.

From the moment Todd first stepped on the ice in the QMJHL, he developed a reputation as a rugged player. His hard-nosed approach to the game meant he was called upon to drop the gloves on a regular basis. By the time he ended his four-year career there, he had amassed 971 penalty minutes in just 265 games. And though he never wanted to be known as a fighter, Todd ultimately would do whatever it took if it meant achieving his goal of playing in the National Hockey League.

Unlike the prototypical hockey enforcer, Todd didn’t just excel with his fists. In his final year, he finished the regular season with 46 goals and a league-leading 102 assists in 66 games. His 148-point total ranked him second in the entire league behind teammate Yanic Perreault.

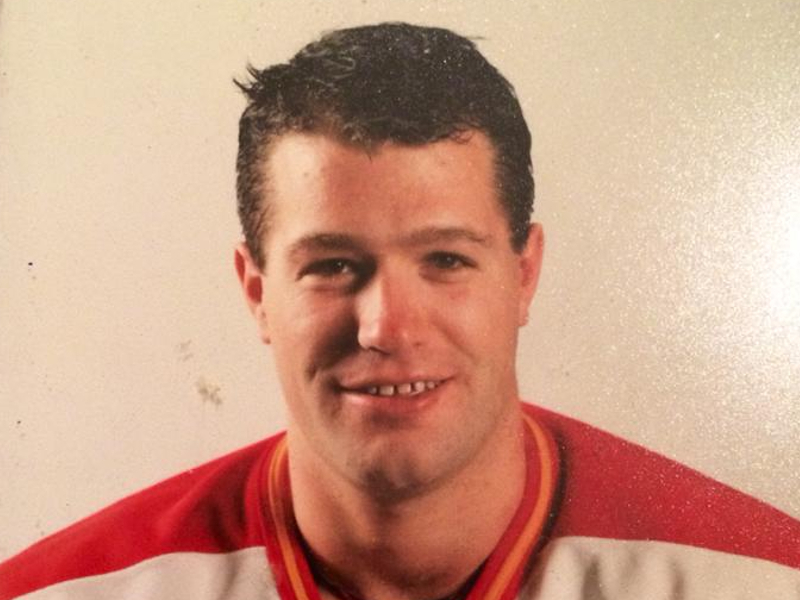

After his junior career came to an end, Todd spent 10 years in the minor professional ranks playing in Canada, the United States, and Wales. But most teams didn’t see him as a scorer or playmaker — they wanted him solely for his toughness and grit. So, he found himself trading punches for that decade with some of the strongest hockey players in the world.

For a burly guy with a reputation as a fighter on the ice, Todd was a calm, sensitive, and kind individual away from the rink. He would send flowers to his grandmother on special occasions, email his mom electronic greeting cards, and even sold old equipment to help finance his sister’s last year of university.

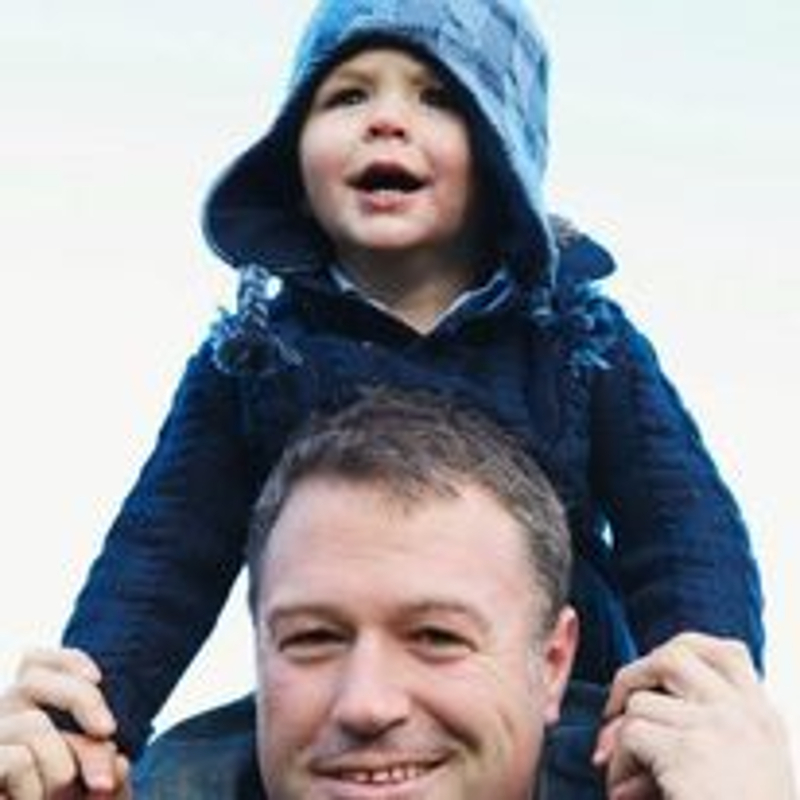

Once Todd finally decided to hang up his skates, he completed his degree and started a family. He put his post-hockey career on hold for a few years to help raise his children, before eventually acquiring a real estate license. He loved his family and was a terrific father, whether putting his daughter’s hair into ponytails and watching her play soccer, wrestling and playing chess with his son, or having the neighborhood kids over for a campfire. He really tried his best to be a good dad.

Todd was diagnosed with more than 30 concussions during his playing career, but it’s suspected the actual number of injuries was much higher. Oftentimes, blows to the head were dismissed, not diagnosed, or left untreated. No one is positive when he first started to show signs of concussion-related issues, but loved ones did notice a distinct change in behavior almost immediately after his playing career ended in 2001. He started partying heavily and living more carefree. And while he remained close to his family, Todd began to bottle his emotions. His family just assumed it was due to difficulty adjusting to life after hockey or struggling with the loss of his father when Todd was 24 years old.

Over the years, as cases of Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) among professional athletes became more widely known to the public, Todd began to suspect his mental health issues could be related to the multiple head injuries suffered during his career.

In 2017, Todd’s worries were confirmed.

After traveling to California for medical testing, scans detected several black spots on his brain, an indication that part of Todd’s brain was no longer functioning. Doctors suggested he learn new activities to help encourage brain plasticity and increase neural pathways, not unlike senior citizens who begin experiencing memory loss. Todd began taking piano lessons, doing yoga with his daughter, and even pruning small bonsai trees.

Still, his condition kept worsening.

Soon, Todd noticed seasonal changes directly impacted his emotional condition. He struggled to adjust and experienced increasing head pain. He was at his worst on nights when the moon was full. He tried using a sunlamp during the dark winter months to trick his brain into thinking it was light out and to help with serotonin regulation.

But it became too much for him to handle, and things began to fully unravel.

After being prescribed medication to treat symptoms of depression, Todd began self-medicating. The headaches that had become part of daily life were worse than ever. He battled substance abuse. His marriage failed, his career fell apart, and he ran afoul of the law. He spent countless hours sitting quietly, rubbing his head. His family tried to provide a support system but often felt helpless as they watched someone they loved turn into a completely unrecognizable person.

Todd then developed cataplexy, characterized by transient episodes of voluntary muscle weakness precipitated by intense emotions. He withdrew more from daily activity and cared less and less about living. He would ask if we thought he was a good dad and say how he ruined relationships with special people in his life.

Even during his struggles, Todd was aware of the brain issues that had claimed some of the lives of his hockey peers. In an online blog he wrote on October 18, 2011, titled “Warning Bells Are Ringing,” Todd addressed the recent deaths of former NHL enforcers Wade Belak, Rick Rypien, and Derek Boogaard. Belak and Rypien both took their own lives after battling chronic depression; Boogaard had passed away from an accidental overdose. All three had later been diagnosed with CTE.

Todd wrote: “My problem with all of this is that there is a far greater issue and problem slowly emerging that has not garnered anywhere (near) the amount of attention it deserves, and this problem, unlike the recent onslaught of head injuries and rule changes, has been around the game forever at all levels.

“This past summer three young men… who were playing or just recently retired lost their lives at very young ages, and I find it terribly disturbing how it seems to be all but forgotten. I can guarantee you one thing, that if these tragic deaths would have occurred to some of the game’s higher echelon players, there would have been a full investigation and research carried out by both the NHL and Hockey Canada, as to how and why these types of tragedies can occur to our players, and they would be quick to react and get some damage control done to protect the NHL’s and Hockey Canada’s pristine image.”

“Why do I believe this is the case? Because I have played the game at all levels and have experienced some of these mental health issues that these players have.”

Todd Gillingham died in an alleyway in downtown St. John’s, Newfoundland in the late afternoon hours of Jan. 14, 2023. He was 52 years old. While some speculated his mental health issues may have finally been too much for him to battle, his cause of death was determined to be the same heart condition that resulted in the untimely death of his father Cavin at the age of 46 in 1994.

Well before Todd passed away, he requested his family donate his brain to science in the hopes of finding answers to the question of why he was in so much pain during his final years. As he told them: “If I could go back in time, I would have given it (hockey) all up in exchange for a healthy brain and life.”

Ironically, Todd gave everything to the sport he loved, but the sport did not return the favor.