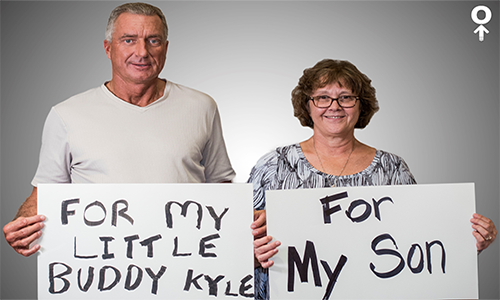

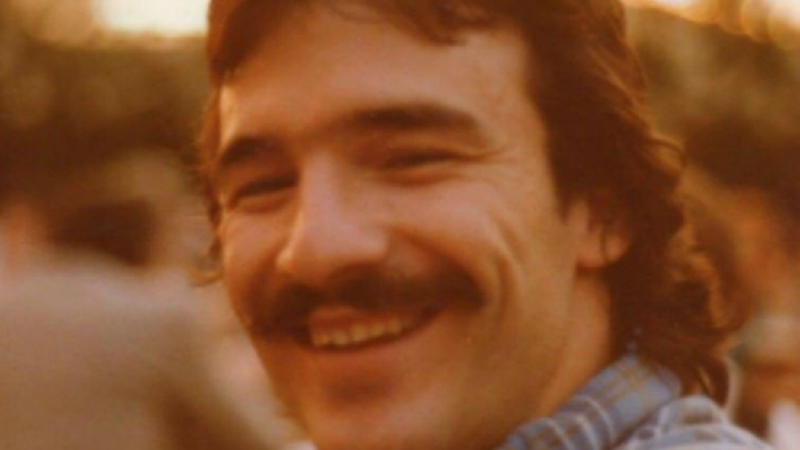

Kyle Raarup

Kyle loved all sports, all his life. He played as much and as many sports as he possibly could, with football and hockey being his favorites. He was a fiercely competitive and driven athlete. He was naturally gifted with speed, agility, and great eye-hand coordination. He was a running back for football, offensive player in hockey, and could play any position he was put in for baseball. Kyle loved it all and loved the friendships that playing sports offered him.

As it is with any dedicated athlete, Kyle was hit many times with only minor injuries. Concussions, in our mind, happened when you got knocked out from a hit, or got your “bell rung”. As the injuries continued and we became more informed about concussions we realized that Kyle had suffered many minor concussions from about 4th grade on. It wasn’t until Kyle was in 8th grade and experienced a check from behind into the boards in hockey when he started having lasting symptoms that we could not control. He waited the recommended two weeks before playing again, only to be hit from behind again when he returned to play. This time he had such severe headaches and other symptoms that he was unable to return to sports or school. Each bump to his head after that caused increasingly severe symptoms for an extended amount of time.

Over the years of seeing innumerable doctors and other medical professionals, Kyle was diagnosed with post concussive syndrome. While it was nice to have a name for what he was going through, Kyle wanted something that would help his symptoms. This seemed to be an elusive goal. He was a trooper and tried every therapy, testing, medication, vitamin, whatever we could find to try to alleviate the pain and memory/thinking difficulties he was experiencing. None worked well, which was a source of great frustration to Kyle. He wanted his brain to go back to normal.

Kyle was able to attend college where he flourished with the assistance of the student services program that allowed him accommodations for his anxiety and inability to handle a lot of sensory input during testing. Kyle loved college and the friends he made there. He was outgoing, cheerful, energetic, and fun to be around. His continued struggles with his anxiety/depression, memory problems and a new stomach ailment overwhelmed him and he took his life on 11/12/15. His brain was donated to the Boston University CTE study in order to find out the answer to his nagging question “what’s wrong with my brain and why can’t it be fixed?”

In December 2016, we found out that Kyle was diagnosed with Stage I CTE along with some brain abnormalities (micro hemorrhages and hippocampus damage) that helped his family get some answers to that nagging question of “what was going on in his brain?” His suicide and the Boston University brain study has helped raise awareness in our community of the lasting impact that concussions can have on the life of a young adult. The loss of a child, brother and friend to many has hit us all hard and will be something that we struggle with for a long time. We are grateful to the Concussion Legacy Foundation for their research and to finally give us some answers, and for their efforts to continue to find answers for future athletes. Kyle would be proud to be a part of this important research and the continued efforts made to understand the devastating affects concussions have on young lives.

We miss him every day, but are proud of who Kyle was and how he has helped us and others understand mental illness and concussions.

Watch: Kyle’s Story: Minnesota Family Raising Awareness About CTE

Justin Raffaeli

Paul Theriault

Fierce on the ice, gentle off it

I’ve started to try and tell Paul’s story numerous times. I somehow feel through writing this, it’s the last bit of him I can still hold on to. The last bit of him that’s mine. He would want it shared, though. He would want the game of hockey to continue in all its glory. He would want others who share his passion for the game to know how multiple brain injuries — or a single traumatic brain injury — can cause drastic damage and be life changing.

I met Paul Theriault in the fall of 1969, the first day of our sophomore year at Lake Superior State College in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. We had chemistry and felt an immediate connection. By the end of our first date, we both knew we were in deep.

Paul asked me to come to one of his hockey games and wait for him afterward. He had a scholarship to play for LSSC’s newly developed program. At the time, I was a novice in appreciating the sport and its charged atmosphere. The fights definitely put me off, but not enough to stop dating him. Eventually, I began to understand what happened on the ice was not a reflection of Paul’s gentle spirit. And so began our lifelong journey with hockey.

The first game of Paul’s senior year against Michigan Tech brought incredible excitement to Pullar Stadium. The noise from the fans was deafening. During a full-speed breakaway, he was tripped and ran headfirst into a stationary goal post, causing a fracture above his left eye. Paul’s helmet came off and the back of his head hit the ice. He was out.

The crowd stayed silent as the team doctor went to Paul’s aid. After a few terrifying minutes, he was able to skate off on his own. He was immediately transferred to the hospital and remained there for the next week, but it was a life-changing injury.

Unable to finish school that year, Paul was a lost soul, trying to deal with headaches, sensitivity to light, loss of short-term memory, and no recollection of what had taken place. His father took him to a neurologist in Marquette, but this being 1972, there was little knowledge of the long-term consequences. However, Paul knew that the game he loved to play was behind him.

Post-playing career

Paul returned to school the following year as an assistant coach for the LSSC varsity team and head coach for the JV team. Both squads had great years, and his future career was becoming evident. After graduating, Paul earned a fellowship to complete his master’s at Western Michigan University by working with their hockey program.

We were married in 1976, seven years after our first meeting in the basement of Brady Hall. I’d finished my degree and was teaching at an elementary school. This afforded Paul the opportunity to become an unpaid coach of the Soo Indians, a local junior “B” team with a mix of players from Sault, Michigan and Sault, Ontario. He had resounding success and knew he’d found his niche. The headaches, memory issues, and sensitivity to light continued, but he managed through them.

When the Soo Greyhounds, a junior “A” team in Sault, Ont., fired their head coach after a disappointing start, they reached out to Paul. He accepted the job, and with a number of future NHL players on the roster, he helped salvage the season and stayed on for another year.

From there, Paul took over the Oshawa Generals for a decade of success in the Ontario Hockey League, including two trips to the Memorial Cup and several coaching awards. He was in his element, guiding players both on and off the ice — as much of teacher as a coach for many young men. Still, the headaches remained.

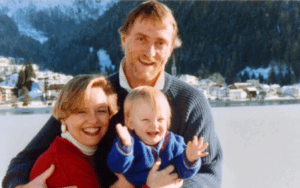

In the spring of 1989, I became pregnant. Paul was thrilled. The New York Rangers offered him a job coaching their farm team, the Flint Spirits. After much soul-searching, we decided it was the right move for that time in our lives.

From the moment our son John-Paul arrived that December, we looked at hockey differently. An offer to coach a team in Northern Italy, with fewer overnights and a 36-game schedule, seemed perfect for us. He signed a contract for one year, but we ended up staying for six. Championships and a well-balanced family life was the perfect recipe.

Ted Nolan, a former player and coach of the Buffalo Sabres, contacted Paul in the spring of 1997 with an offer to join him as an assistant coach. Together, we made the hard decision to return stateside. Coaching in the NHL had been a longtime goal and here was Paul’s chance.

Once again, Paul was successful and the Sabres finished atop their division. However, a contract dispute and the inner workings of pro hockey put an end to his NHL tenure. Paul returned to Jr. A hockey and Italy for some years before taking his final coaching job with the Nippon Paper Cranes in Hokkaido, Japan, where he won the West Asia Championship.

Declining health

By this time, Paul’s behavior started to noticeably change. Though he knew he wasn’t always himself, he quietly went about bringing a Jr. B team back to life at Pullar Stadium. He bowed out of coaching when it became clear his mental state was deteriorating. That team, the Soo Eagles, is still playing today — a lasting legacy for Paul.

On a visit to southern Ontario in 2010, a former player and friend noticed Paul’s state and arranged for him to see a concussion expert at the University of Toronto. CTE was mentioned, and the doctor recommended we go to Mayo Clinic. There, doctors determined he may be dealing with the possibility of CTE, Alzheimer’s, and dementia. For the next five years, we worked with the team at Mayo but nothing slowed Paul’s decline.

Later in the year, we reached out to the Boston University CTE Center to discuss brain donation. Paul had developed aphasia, and while he couldn’t speak to groups about the dangers of concussion, he could pledge his brain to research. By 2012, I retired to care for and spend time with Paul.

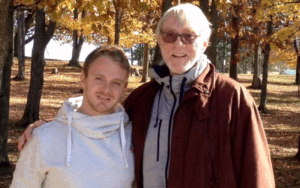

Former Oshawa Generals players and Paul’s college teammates held “Tribute to Turk” golf outings in 2012 and 2014 to raise money for his medical expenses. The impact he had made as a player and a coach shone brightly. He was a well-loved man.

The winters are notoriously long in the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Paul hated the cold, so we went to Florida for a couple months every year to escape the snow. I had business cards made for Paul’s pocket giving my contact information should he wander. By 2015, his decline was to the point we could no longer head south.

During Paul’s last two years at home, he experienced paranoia, hallucinations, anxiety, and fear. He couldn’t express himself and, I believe, soothed himself with constant humming. Fortunately, he wasn’t violent nor suicidal. He simply didn’t know the state he was in.

Paul was always good-natured and positive, and he remained that way even late in life. By 2017, caregiving had become incredibly difficult for me, and my own health was suffering. We realized this couldn’t continue. After much persistence, I was able to get Paul into my first choice for long-term care at the Finnish Resthome, a nonprofit in Sault, Ontario.

It was the most difficult day of my life. Leaving Paul there nearly broke me.

There was enough of the old Paul left to woo the staff and he quickly became a favorite, even while cursing them during showers and changing clothes. They gave him his best days for seven years, though his behaviors early on were difficult. But with proper medications and a compassionate staff, he didn’t act that way for long. Once I felt complete trust, I was so grateful for the professionalism and empathy shown to us both. I still think of those people every day.

When COVID hit, the home was shut down for months. Once I was allowed to visit again, I needed to show proof of a negative COVID test before crossing the Canadian border. Donning my protective covering and mask, I could only see Paul for a short period of time. I learned that in my absence, he’d stopped walking and was in a wheelchair. He also needed assistance to eat. I would wear my perfume in the hopes he’d recognize me and enjoy listening to Bocelli together. Sometimes, I felt he did.

Paul’s Lasting Legacy

In his final years, Paul only existed, a shell of himself. He was always a very healthy man in tremendous shape, and his body simply refused to give in. I advocated endlessly for Medical Assistance in Dying to be expanded to dementia patients. Family and friends prayed for him to be set free. On January 3, 2024, Paul’s journey on Earth came to an end. His brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank shortly after.

In February 2025, we had a virtual visit with BU CTE Center researchers who informed us of Paul’s diagnosis: stage 4 CTE. We pray the donation of his brain helps advance research to eventually diagnose CTE during life. We hope it raises awareness of the need for proper concussion protocols through all levels of hockey. We also call on the NHL to acknowledge the harm players put themselves in with every game.

Finally, I would like to address the impact of CTE on families. The mental and physical health of caregivers — whether they are children, spouses, or parents — are affected as they watch a loved one slowly slip away. Economic changes take place. Isolation becomes part of the process. It’s a very long journey, even after the person is gone. Grief is not linear. I can’t wait for the day when we no longer have to worry about this terrible disease.

Christopher Tschupp

Rick Williams

Beginning this piece of legacy writing was not an easy feat for myself, as I still find immense heartache in the loss of my father, friend and hero. I feel it appropriate to state before this piece: “This one’s for you dad, I’ll give it a 110%!”

Beloved husband, father, son, brother and friend

By Sheena Williams, Rick’s daughter

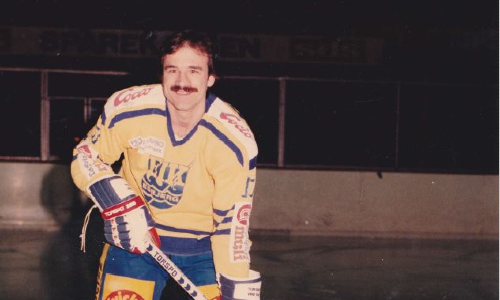

Born in Lampman, Saskatchewan to Betty Lou Bryce and “Butch” Clarence Williams, Ricky Emil Williams joined his older brother Russell, where they spent a short time before moving to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. It was during dad’s days in Saskatoon where he picked up his deep seeded love for the game of hockey.

Dad played for the SJHL Saskatoon Olympics, before joining the Saskatoon Blades, playing in the WHL. It did not take long before he was traded for his arch nemesis/best friend George Pesut in Victoria at the ripe age of 17. I will never forget dad’s stories during this time as he described – “just how lucky hockey players have it these days…back in my day, I had to bus it with no heat to a place called Flin Flon, Manitoba to play a game, and back again!” I believe that if you were lucky enough to know dad, you were privileged enough to learn about Flin Flon, Manitoba.

From there, dad played for several different teams, including the Spokane Flyers and the Nelson Maple Leafs before attending the University of Calgary on a hockey scholarship to join the Dino’s. It was here that Dad met many of his longtime friends – the FOR’s (Friends of Ricks). This was also the time when dad met my Nana, June Tarves and their wonderful family. The story goes that dad was looking for a place to stay while attending University. Lucky for him, his friend Shane knew the perfect place – at his mother’s house. Now Nana, being the ever welcoming type could not say no, and allowed dad to stay for the period of his kinesiology degree. Dad quickly became a part of their family, and soon considered June to be a second mother.

Dad’s time spent at the University of Calgary was a tremendously joyous time. Not only was he able to meet many of his lifelong friends, but was awarded Canadian Defensemen of the Year. An incredibly skilled hockey player, dad not only played the role of defense, but also as the team “goon.” Short in stature, dad always mentioned needing to make up for his size in other ways which included fighting and/or taking a dive in front of the puck; whenever dad played, he played his heart out.

From University, Shane Tarves (June’s son) was able to pull some strings to have dad join him in Europe to play. Dad played in both Denmark and Germany, where he met his wonderful wife Susanne (originally from Denmark). Dad played several years in Europe, before deciding to move back to Calgary with Susie to start a family, and lay down some roots.

Shortly after settling down in Calgary, Susie became pregnant with their first child, Sheena (that’s me), and their son Luke a few years later. It was at this time that dad began his work with the Calgary Board of Education as a substitute teacher. After some time at different schools, dad was able to establish a position as a Phys Ed teacher at Fairview Junior High.

Dad’s love for teaching was undeniable. The passion that he poured out into teaching children was an enviable quality of any teacher; to state it more blatantly, dad just “got kids, it was a part of his being”. He was able to connect with them not only on a surface level, but was able to impact and change many lives over the course of his career. To solidify just how impactful dad was, a message from a former students…

“I was a student at Fairview junior high. I was not the most athletic kid and was picked on constantly by the other students. I fell into depression through-out these three years and was almost ready to quit. But one day when I was too ashamed to leave to the locker room Mr. Will came in to talk to me and I will never forget the words he said to me. He told me no matter how many times you take a hit you have to get up and fight for yourself, it doesn’t matter what the crowd thinks it’s what you do that matters. This was the first time in a long time that I had felt like some one cared for me and these words stuck with me. Because of what Rick said to me I am now in university following my dreams. Rick Williams changed—no saved my life without even knowing, and for that I am thankful. He was a great man who treated students with more respect and compassion than any other person I have ever met.”

For those of us lucky enough to know dad, we are all better for it. In both sickness and in health, dad was always a presence that one would gravitated towards – he was magnetic. Growing up, I always thought of my dad much like any other dad – strict, rule making, expectation upholding, and curfew setting…but it was not until my later years that I realized just how magically special my dad truly is, and was. I am confident in saying that I would not have turned out to be half of the woman that I am today without the love, guidance and expectations that my dad placed upon me each and every day – “just be a good kid and good things will come to you” he would repeat – something that my brother Luke and I will never forget.

When dad became ill, it was, at first a gradual decline. Small things were forgotten such as key placement, what we ate for breakfast, etc. – everyday things that many people tend to forget or misplace. From here, it grew more and more present that dad was losing both his short and long-term memory. He began to forget directions to familiar places such as the hockey rink and Tim Hortons; it was now that he began to become more erratic and fearful. Dad knew that he was changing, but did not understand why, or to what extent; none of us did.

Dad was placed on Long-Term disability from work, and took a turn for the worst as he began losing most of his working memory, as well as fabricating stories that he was sure took place. Due to the severity of aid that Dad began to require, he was welcomed into the care of health professionals where he was able to receive the assistance and monitoring that he began to need. This decision was heartbreaking to his immediately and extended family. Sleepless nights, tears and angst accompanied most days spent missing and worrying about dad. Could he come home? Did he understand why he was there? Is he upset with us?…the uncertainties never seemed to subside in the hearts and minds of loved ones.

After some time, dad was placed in the Bethany Harvest Hills Care Centre, and what a blessing this was. The atmosphere, nurses, and healthcare professionals were a Godsend to dad and to our family. Dad was not only treated with compassion and respect, but was most importantly loved by each person that cared for him. They made Dad a priority each and every day.

Dad spent the rest of his life at the Bethany Care Centre, before passing away in his room November 15, 2014 with his family all present to send him off. At the age of 60, this was not easy to accept, but was understood based on dad’s condition. We later found out that Dad was also diagnosed with Colon Rectal Cancer, as well as pneumonia in his final days. I can speak only for myself in saying that the amount of heartache still felt in regards to the loss of my father is overwhelming.

When dad left us that day, he took a part of each of us that will never be replaced. I still feel dad in all that I do, and remember many of his quotes and qualities that I both live by and attempt to emulate on a daily basis. We lost an incredible human being that day, but God gained an angel. I often feel as though God took dad too early and that I wasn’t ready to lose my father, but now understand that he is always with me, and with all of us. I can still hear him telling me to weed whack the grass edges a bit closer, asking me if I’d like to come to “Timmies” for a coffee, or asking me what I was going to order off of the restaurant menu so that he could order the same.

We love and miss you more than you will ever know dad. I promise to always “be a good kid”, and know that good things will come to me because I am a part of you.

Until we meet again Dad – I love you.

Sheena Lou Williams

Click here to read Rick’s story from the Global News.

Click here to view the news clip from Alberta CTV News.