Bruce Cutler

Cade Douglas Carlson

Alexandra “Owl” Hinks

Jacob Sinclair

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

Jacob “Jake” Dean Sinclair was born at 4:18am on October 23, 2006, in Stafford, VA. Funnily enough, he wasn’t yet known as Jake at the time. I woke up that morning at 3:00 a.m. and we barely made it to the hospital, still undecided about a name. My husband Chris’ grandfather had decided upon himself he would call our child Jake, no matter what anyone else said. So, we landed on the name Jacob Dean, after both of our grandfathers. To teachers, friends, and strangers he was Jacob but to family, he was Jake.

Jake was the baby of the family, following our first son Tyler (born in 2000) and our daughter Autumn (born in 2004). He loved both his siblings immensely. I still remember the day Jake was born, Autumn walked into the room demanding we give her the baby. She adored him as if he was a real-life doll, picking out some of his clothes even into his teens which he wore without hesitation.

From a young age, Jake was caring, sweet, bright, respectful, and a wonderful friend to all. He had a big heart and loved making everyone laugh.

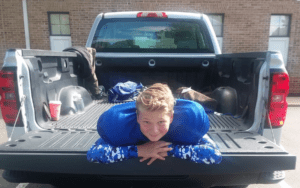

And of course, Jake’s hair. He’d probably tell you his curly hair was his best quality.

Growing up, Jake was your typical teenager. He enjoyed going to games at school, to the movies or concerts with friends, and playing his Xbox. Jake especially liked tagging along with his sister wherever she went – on Target runs, to Goodwill, out for ice cream, and dog sitting. As with anyone his age, he was constantly on YouTube and TikTok, showing us videos he thought were funny. And at family gatherings, Jake loved talking with uncles and cousins about his hometown team, the Washington Commanders.

If Jake wasn’t watching sports, he was playing them. He wanted to play football when he was still in preschool but didn’t officially start until age eight, as soon as he was old enough for parks & rec. Jake then played through his freshman year of high school but was recruited to the lacrosse team and made the switch. He also wrestled for a few years in middle school, winning most if not all his matches.

In football, Jake switched between offense and defense and there were games where it seemed like he never left the field. He thrived as a defensive end, always breaking through the O-line and sacking the quarterback. Because of his prowess, there would always be two or three guys on him every play.

Jake’s first diagnosed concussion occurred in April 2023 during a lacrosse game, when he ran headfirst into another player. He was evaluated by the athletic trainer who sent an email to me and his teachers a day later, informing us Jake had suffered a concussion. When I told him I was making a doctor’s appointment to get checked out, he only complained of a headache and light sensitivity otherwise he felt better. But after Jake passed away, I saw from old posts on his phone he only said that so he could get cleared to keep playing.

A second concussion occurred a few months later in August, after Jake flipped a golf cart at work. He had a visible mark on his head and complained of a headache. The physician said Jake had a “mild concussion” and to simply avoid light and rest. When I again reviewed text messages, I realized he was asking for headache medicine multiple times a week, sometimes more than once. He also mentioned having insomnia in social posts. On the day Jake passed, he told his girlfriend he almost fell down the stairs from dizziness.

We only found out these details after Jake’s passing once we had access to his phone. We had no idea how much he was struggling as he’d blocked the entire family from his social media accounts. I don’t think he knew these were possible concussion symptoms or understood what was going on in his head.

After Jake’s concussions, we noticed changes in his behavior, including impulsivity, aggression, lethargy, and substance abuse. Looking back now, it became so extreme we should have suspected something more than just a troubled teenager going through puberty. We also thought some of his behavior stemmed from the few years of isolated virtual learning due to COVID.

As a parent, I didn’t know what to do and felt like I was failing him. I’m sure there are many other parents who feel the same way about their kids. At the time I didn’t know these symptoms could stem from a concussion, so it wasn’t even on my radar. I’d catch him smoking marijuana and see Fs on his report cards. When I tried to talk to him, he would go off on me, saying what a bad parent I was and how I ruined our relationship over a little weed, which he said helped him relax.

In the last year of Jake’s life, our relationship was strained, and it affected the entire household. You can only try to ground someone so much, but he would still sneak out and do whatever he wanted. Especially once school started, I think he was able to smoke all day without any consequence. We barely recognized this version of Jake. In my mind, I just hoped this was a phase and we could get through it.

On the day Jake passed away, it was snowing so there was no school. It started off like a typical day; Jake had slept in then after lunch we spent time making plans for our annual trip to the Outer Banks. He also mentioned wanting to sign up for the junior fire academy during his senior year. I agreed, if he turned in all his missing homework assignments which had started piling up.

While my husband and I were making dinner and cleaning up around the house, Jake asked if he could go to a friend’s house. I told him no since the roads were bad and he hadn’t yet improved his grades. Jake snapped and started yelling at me. I told him I wasn’t going to argue, and he needed to calm down. He took his food and went to his room. Our daughter Autumn went to check on him after dinner but found his door locked. When we got inside, Jake was unresponsive.

That evening and the blur of days after, we tried to process what had led to Jake’s death. My husband mentioned the concussions and if they might have played a part. Following the funeral, my stepmother sent me an article featuring Wyatt Bramwell, saying his story sounded just like Jake’s.

Reading Wyatt’s story, I was astounded by the similarities. While my husband had heard of CTE before, this was the first I learned of the disease or any long-term effects of concussions. And both of us didn’t know it could affect someone so young until the article. I then went through other Legacy Stories on the CLF website – Austin Trenum’s was another which read just like Jake’s. One minute, everything was fine and he was making plans for the future. The next, we had an argument and then he was gone.

We had no idea the connection between concussions and suicide risk and don’t believe Jake did either. Since his passing we’ve learned his struggles were not at all uncommon for someone healing from a brain injury. Multiple research studies have shown a link between concussion and suicide risk, with one study finding those who suffer a concussion are twice as likely to take their own lives. That is such an important statistic for all parents to understand, especially those who have children who play contact sports!

I got in touch with the UNITE Brain Bank and due to the circumstances of Jake’s death, his brain was unable to be studied. Though there may be no official diagnosis, I’m sharing Jake’s story because I want other families to know what to look out for when their child has a concussion. I also want the entire athletic community, from trainers, coaches, and medical personnel, to know they need to better educate players and families/caregivers about Post-Concussion Syndrome and suspected CTE. And to those currently suffering, I want you to know there are resources out there to help you.

Jake was so loved by so many people. No one had any idea he was depressed or suicidal. I just wish Jake had known he was that loved while he was still here.

_____________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Mike Albarelli

Mike Albarelli was a magnanimous man. He was the type of guy who walked into a room and would instantly lift the room’s energy. His smile was as big and broad as his body and he had a way of making you feel like you were the most special person in the room. He loved good conversations, funny banter, and making genuine connections with people. He had a deep belly laugh and a love for his friends and family as deep as the ocean. Our children meant everything to him.

Mike and I met at Brown University where he was captain of the lacrosse team. Our very first conversation was about a Britney Spears concert we had both gone to. I was completely taken aback that such a big, burly guy had such a soft and kind soul. A bear on the outside and a mush on the inside, sensitive but strong; he was my dream combination. We spent countless hours sharing stories, laughing, hanging with friends, and creating a meaningful life together.

He was known by his teammates as an intense player who wore his heart on his sleeve and took all losses personally, whether he had played incredibly or poorly. He was the captain of every team he was ever on. He was the epitome of a good teammate. He intuitively knew what his teammates needed to be motivated to do their best. He would listen to music to pump himself up before a game, and then once adequately amped, he would share his energy with the rest of the team.

He did everything full-force. He wanted to be the best at everything. The best athlete, friend, husband, father, brother, the best at it all. He made the most out of every moment he spent on this earth. From skiing, to fishing, to golfing, to traveling the world, he wasn’t someone who ever sat on the sidelines.

He always told our boys that three things were important: always do your best, always finish what you start, and practice makes perfect. He lived up to these ideals until he couldn’t anymore. His unfolding is hard to write about because he had so much pride and when he was in a good place, he was unstoppable.

I feel like I slowly started to lose him a few years before he passed. Around 2015, he became more distant and more disconnected from his friends and family. He fell into patterns of drinking that created a major divide between who he wanted to be and who we were seeing. He and I both knew something was wrong. His ability to regulate his emotions and the emotions of others became paper thin. He tried so hard to be the best dad and the best husband, but he seemed pulled into a darker world, a place he could not find escape from for too long. It was hard on all of us, but hardest on him. I saw so many brief pockets of hope and clung onto those for dear life.

In the end, his demons won the battle. On July 30th, 2018, while intoxicated, Mike fell down the back stairs of our home all the way to the concrete foundation of our house. The impact led to a brain injury that ultimately ended his life. He was just 38 years old.

A year later we received confirmation from researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank that Mike suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). This came as no surprise to me and validated our worry that he was struggling more than he ever led on.

At the time of his death he was still highly functioning. He hadn’t started losing his memory, and he was still able to successfully operate as a successful CEO of a company. He may have seemed fine to others, but he was battling something internally that was pulling him away from himself. As his wife, it was hard to watch the man you love be unable to take care of himself and his family the way he would want to.

Mike’s impact on this world was profound. He would want his legacy of generosity, kindness and passion to be passed on. I am committed to working on spreading knowledge about CTE and helping families and loved ones learn to navigate the trauma and grief that comes with this degenerative brain disease.

James Canino

Jared Crippen

This story adheres to the Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide from reportingonsuicide.org

Laura Lowney entered her son Jared’s room in Brick, New Jersey, at 6:00 a.m. on the morning of April 23, 2019. He wasn’t there. This had happened before. Jared could be any number of places. He could be lifting at the gym. He could be surfing. He could be at the lacrosse fields. But an ominous feeling told Laura something was very wrong.

The night before, Jared had left to go to a party. He returned late that night and went to Laura’s room to say goodnight. Jared was 16, popular, handsome, and athletic, but he was never ashamed of how much he loved his mother. He hugged her tight, then bent down at the foot of the bed to kiss the family cat, Nala. Jared came back and hugged Laura again.

“I love you mom.”

“You seem mellow, Jared. Are you okay?” Laura asked.

“I’m okay. I’m just tired,” Jared said as he left the room.

Golden Boy

Born on December 6, 2002, Jared Crippen was special from the start. Baby Jared was constantly smiling. Tantrums were not in his repertoire.

Jared’s teachers found him adorable and appreciated his work ethic and infectious energy. He got along with everyone, worked hard, and thrived in school.

Jared was also naturally athletic. He got on a surfboard and balanced himself in a lagoon for the first time in fifth grade. Twenty-four hours later he was riding waves. In just one day, a lifelong hobby was born.

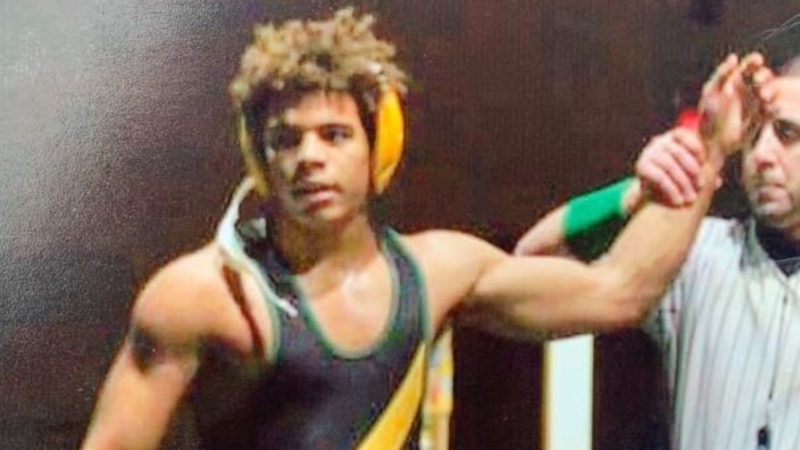

Jared wanted to wrestle and play lacrosse. Jared pleaded to follow in his older brother Jaden’s footsteps as a wrestler, but Laura held him out of competition until sixth grade. Once he started his strength, coordination, and speed allowed him to excel in both sports. As a freshman at Brick Memorial High School, Jared made the varsity wrestling and lacrosse teams.

Jared reached the regional championships for wrestling while competing against juniors and seniors. College coaches took note of his athletic ability.

“He was a caring friend and teammate. He had that ‘it’ factor. I could feel it. People were attracted to him,” Jared’s wrestling coach Mike Kiley said. “When he would walk into the gym, students would flock to him. He was just that type of kid. You wanted to be around him.”

In lacrosse, Jared’s ability to win face-offs and fly up the field untouched for goals had him dreaming of playing at Johns Hopkins.

He also excelled in his one season of football his freshman year, but the sport wasn’t for him. Football’s demands made it hard to paddle out later in the day to surf. Despite prodding from coaches, Jared called it quits after one season.

Surfing wasn’t a team sport in the traditional sense, but Jared found community along the beach with friends, surfers from neighboring schools, local riders, and even small business owners who, like most people he encountered, adored him. Surfing offered Jared something football, wrestling, and lacrosse never could.

“Surfing was no competition, no coaches, just him and the ocean,” Laura said. “He was free.”

“Mom, I don’t feel so good.”

Heading into his sophomore lacrosse season, Jared was eager to build off the success of the previous year. He was starting at midfielder for the Mustangs.

With three minutes left in a preseason scrimmage on March 14, 2019, Laura momentarily turned away from watching the game when she heard that Jared had collided with a teammate.

Jared collided face-first with a teammate and was sent to the ground. He came off the field, where Laura went to check in on him. Jared waved her off, assuring her he was fine.

Once the game was over, a still-helmeted Jared told Laura he was going with his friends to IHOP instead of coming home for dinner. About an hour later, Jared came home and walked up behind her in the kitchen.

“Mom, I don’t feel so good.”

Laura turned around to see Jared for the first time without his helmet on. There was a gash on the left side of his face. He said his head was pounding and his body felt tingly and almost numb. Without hesitation, she took him to the hospital.

ER doctors diagnosed Jared with a concussion. They told him to lay low; no screens for a few days, no exercise.

Laura watched Jared sleep the night they returned from the hospital. Doctors reassured her he would be fine, but she wasn’t one to take chances.

For the first three days after his concussion, a splitting headache and extreme sensitivity to light kept Jared from leaving his room. Laura delivered food to him and blacked out his windows to keep the light out.

Eight days after his concussion, Jared said the kitchen light bulb was “bright like the sun.”

Eventually, Jared could move around the house if he had his sunglasses on. His doctor cleared him to return to school. Lacrosse was temporarily off the table, but Laura took him to practice so he could watch his team through sunglass lenses. She demanded his coaches not let him do anything physical. They obliged.

“No, mom. I’m fine.”

Two weeks after the concussion, Jared went back to the doctor. He went through a battery of tests on his memory, vision, and balance. During the balance test, Laura saw the normally sturdy Jared struggle to maintain his balance on one foot. Still, the physician said Jared passed the test.

“What do you mean? He looks shaky. He usually balances a lot better than that,” Laura said.

Jared’s doctor reassured Laura and Jared his balance was satisfactory. He was ready to seek full clearance from the athletic trainer who went ahead and cleared him to fully participate in practice. He was set to play in Brick Memorial’s next game.

Jared was back in action, but Laura didn’t stop checking on him. After every practice she asked if he was feeling alright and if he had a headache. Each time she received the same response.

“No, mom. I’m fine.”

In the next few games after returning to play, Laura noticed a change in his playing style.

Jared normally received the ball and made a beeline to the goal to take a shot. The trademark speed was still there but gone was his usual aggressiveness. Jared was routinely passing up wide open shots to send teammates the ball.

“I’m just playing relaxed, mom. I’m just having fun,” he assured her.

Laura noticed Jared was frequently picking at the left side of his bristly head of hair. She called him on it, but Jared brushed that off too. His hair was knotted. Laura’s questions were also beginning to receive an uncharacteristic shortness from Jared.

Jared got rides to school from friends. He was usually ready to go in the mornings and waiting on them to arrive. Now, Laura had to get Jared out of bed because his friends were waiting on him.

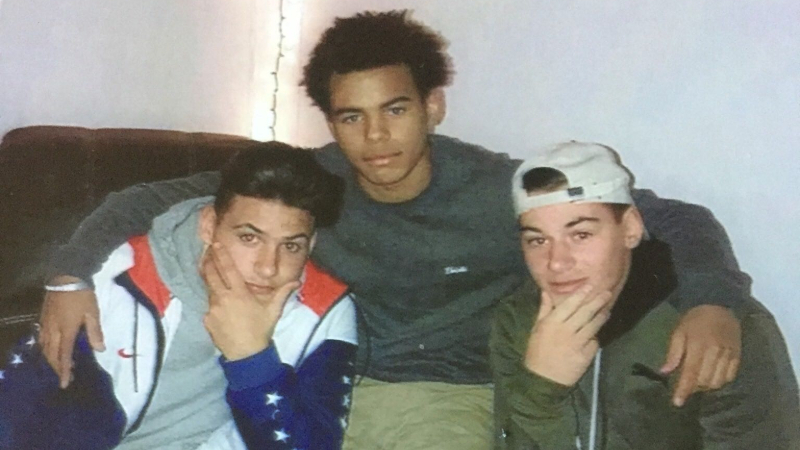

Jared with Joey Zalinski (left) and Anthony Albanese (right). Zalinski and Albanese later switched their soccer and football numbers, respectively, to Jared’s number 7.

That April, Laura found her antacid tablet container in Jared’s room. Jared said he overdid it at Buffalo Wild Wings.

Later that week, Laura had to pick Jared up from school because of his upset stomach. Again, he said the wings were the culprit.

The change in playing style, the attitude, the sleeping in, the hair picking, and the stomach issues were all peculiar for Jared but not peculiar for a typical teenager. Laura was slightly concerned about the changes, but they all had reasonable explanations. Teenagers get tired. Teenagers have attitude. Teenagers are about the only people who would eat the ghost pepper wings at Buffalo Wild Wings.

Normal teenage stuff, she thought.

On April 22, 2019, Jared came home and sat on the couch with a burrito in-hand.

He laid next to Laura to debrief about his day. He had completed his first Driver’s Ed drive with James Brite, who was also one of his lacrosse coaches. It went great. He was set to get his learner’s permit the next day. He talked with Coach Brite about next season. He sent texts to teammates about the pasta party Laura would be hosting next week before the big game against rival Brick Township.

He left for a party and returned home later that night to say goodnight to Laura and embrace her for the last time.

“I can still feel that hug,” she said.

On April 23, 2019, Laura woke up to find Jared wasn’t in his room. She called Jared’s best friend Anthony, who like all of Jared’s friends, called Laura “mom.”

“I don’t know where he is, mom.”

Laura jumped in her car and drove around town to look for Jared. He wasn’t at the gym. He wasn’t at the lacrosse fields. He wasn’t surfing.

Frantic, Laura drove home to try and collect herself. On her way, she saw a police car pulled over on the side of the street. She begged the officer to help her find Jared.

He told her to hold on a minute. Almost immediately detectives pulled up. Her heart sunk when the detectives approached her.

“Jared’s gone,” one of them said.

Jared Crippen took his own life. He left a note, written in his signature cursive handwriting. He was 16 years old.

Jared’s wake was on April 27, 2019. More than 1,500 people came to pay their respects.

Laura received a letter in the mail a week after Jared’s death from a mother of one of his classmates. She explained how her daughter suffered from anxiety and didn’t have many friends at school, but she sat next to Jared in a class. Whenever she walked into class, Jared took his headphones out, smiled, and spoke to her like few others at school would.

In the grief-filled weeks to come, friends and family came to console Laura and the rest of Jared’s family. More sympathy. More love for Jared. Still no answers.

“Jared? Not Jared. Why would he do something like that? He was so happy.”

But one night, a family member asked Laura: “Didn’t Jared have a concussion not too long ago?”

“Yeah. Why?” Laura replied.

“You better look into that. Because it could have something to do with what he did.”

So, Laura looked into it. Her research started a cascade of information-gathering. She learned more about concussion symptoms than she was ever told from any doctor or athletic trainer.

She learned after concussion, an athlete should be slowly reintegrated into their sport rather than going from zero to full-participation like Jared did. She learned about Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) and the potential for concussion symptoms to last longer than two weeks. She learned about the depth of emotional symptoms, including depression and anxiety, that can accompany concussion.

Her research led her to connect Jared’s string of odd behavior in the last month of his life to his concussion. Her instinct about the wobble in the doctor’s office. The upset stomach. The short fuse. Even the hair-picking could have been an attempt to relieve pressure in his head.

And those were just the signs she knew about.

In the weeks following Jared’s death, his friends were mainstays at Laura’s house. They ate meals there and shared stories about Jared. They laughed, cried, and told Laura other ways Jared was struggling.

She learned Jared skipped a second period, but not to get into any trouble. He skipped class to sleep in a friend’s car.

She learned Jared started drinking at parties a couple of weeks before his death. Friends say he left multiple parties because he would get upset and start crying for no reason and want to leave. Once, he and his girlfriend were at a party for just 10 minutes before leaving because Jared’s head hurt so badly.

Jared was usually the life of the party. At the party the night before his death, he sat quietly with earbuds in. Friends saw him with tears in his eyes before he left.

According to a 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the rate of suicide is twice as high for individuals who have experienced a traumatic brain injury.

Suicide is a complex public health issue, involving many different factors. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide most often occurs when stressors exceed current coping abilities of someone suffering from a mental health condition. The hopeless tone of Jared’s note began to make more sense.

Laura believes Jared never fully healed from his concussion. When he took his life, Jared wasn’t the happy and carefree kid he had always been.

“These are all the things I found out after my son was gone,” Laura said. “If I would have known these things, my son would still here. I would have immediately gotten help.”

Laura sought community to cope with her loss. She soon found out she wasn’t alone.

She spoke with Graham and Cathy Thomas, whose son Zander took his life following a concussion in 2013. She learned about Austin Trenum, who died by suicide in 2010 at age 17.

“My 16-year-old son Jared took his life 5 weeks after a concussion. I don’t know how to put my story into words… yet I have so much to say,” Laura said in a message to CLF.

CLF connected her to Gil and Michele Trenum, Austin’s parents. Talks with the Thomas and Trenum families have given Laura comfort and support. They can empathize with the inescapable guilt Laura feels and they can also remind Laura about the role a concussion likely played in Jared’s story.

“There are people out there to help you get through this,” Laura said.

“I wouldn’t wish this on anyone else.”

In the face of tragedy, Laura hopes Jared’s story can affect change. She has simple messages for parents and athletes. Messages that could have saved Jared’s life.

For athletes: it’s never worth it to play through a concussion or shake off your symptoms. Don’t play with your health, and don’t risk your friends’ health either. If a teammate is acting out of character after a concussion, as Jared was, let an adult know.

“It’s not going to help you get back in the game. If you’re not feeling well, it’s going to make it worse. You’re not going to perform like you should,” Laura said. “Wait until you’re ready, until you’re okay to go back in, because this is your life.”

For parents, Laura learned three key lessons. The first is concussion needs to be taken seriously. The second is to seek out a concussion clinic to find a specialist for your child’s concussion management. And lastly, any abnormal behavior after a concussion should be taken seriously.

“I want my son here. I could care less about how long he was out from his sport,” Laura said. “He needed to get well. I know he wouldn’t be happy, but you know what? It’s his life. And I didn’t know it was his life. Now, I know it was his life.”

She hopes athletes, parents, teammates, coaches, teachers, and everyone around a young athlete knows the role they should play in concussion management.

“It takes a village. Everybody has to watch that kid.”

“Jared was out there with us today.”

In late June 2019, family and friends congregated to celebrate Jared’s life with a Paddle Out in Manasquan, New Jersey. Christian Surfers of Manasquan organized the Paddle Out, which is a high honor in surfing culture, reserved for respected members of the surfing community.

The wake in April was full of heartache and confusion. The Paddle Out was a celebration.

Rob Brown, a coach and teacher of Jared’s, spoke at the Paddle Out. So did Anthony Albanese, the friend Laura called the morning of Jared’s death. Anthony later switched his football number to Jared’s #7. People wrote notes about Jared on seashells before sending them into the water. The group of Jared’s friends and other surfers paddled out to the ocean with flowers on their boards. Riders formed a circle, they prayed, and some of Jared’s ashes were spread into the ocean.

“Jared loves everyone who is here today,” Laura said as she closed the day’s festivities. “I need you all to know that if you ever have a concussion or you’re feeling anxious or sad or anything, you have to go to a parent or a coach. They can get you the help you need.”

When riders paddled out that day with flowers and ashes, the Manasquan waters were flat. Then, almost right after Jared’s ashes were poured into the water, waves started crashing. One surfer approached Laura and said what everyone else was thinking.

“I just want you to know Jared was out there with us today.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Elijah Glover

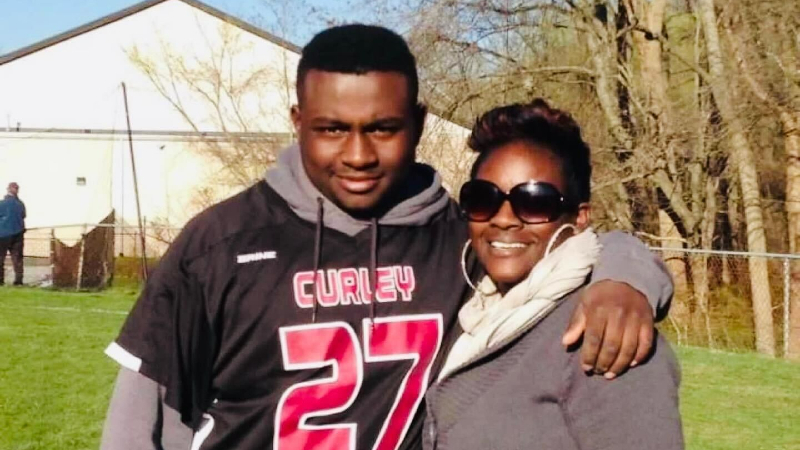

Elijah James Glover was my eldest son. He was captivating and determined. He was not easily swayed and believed deeply in the love and commitment of family. Even as a young child he showed great appreciation for those he loved. I remember him working at yard sales and cutting grass for money to buy me birthday and Christmas gifts. He was funny, clever, intelligent, and wise beyond his years. And though he was bigger than the other kids, he was never aggressive and didn’t get into fights.

Elijah mastered everything he attempted and played with his whole heart. Elijah played baseball, wrestling and basketball, but his heart was in lacrosse, and his spirit simply embodied football. Elijah started little league football the summer of his fifth birthday. He practiced diligently and played at maximum potential. I was such a proud mom watching from the stands, in awe of his abilities. The onlookers shouting his number, “25” and his name, “E” was exhilarating. I felt a sense of pride and honor at who Elijah became when he put the stick in his hand or when he broke from the team huddle and they yelled, “Down! Set…”

Elijah suffered many blows to the head we now realize were concussions. I wondered if they would have a lasting effect on Elijah’s brain. I started comparing the impact sustained by football players to those of boxing contenders and champions. I remember Elijah’s last hit to the head in 2015 after a lacrosse game when he was 17 years old. He reported seeing stars, feeling nausea, and requiring some assistance off the field. The concussion concerned me enough to make an appointment with a concussion clinic near our home in Baltimore, Maryland.

Shortly after the injury in 2015, I noticed remarkable changes in Elijah’s mood. He was usually reserved and calm, but he became irritable, constantly pushed boundaries, showed outward signs of aggression, made poor choices, and started smoking marijuana. Elijah forgot family memories and even when prompted by photos he simply could not remember they happened. He no longer went out with friends and became unmotivated. He was depressed and shared dark thoughts and feelings. He preferred to be asleep over being awake. Our relationship, which had always been as strong as a rock, deteriorated.

Elijah began an uphill battle with addiction. He was diagnosed with depression and bipolar disorder and was prescribed medications which he often abused, compounding his issues. After further consideration and research, I realized Elijah’s symptoms mirrored CTE. I vehemently disagreed with the mental health diagnosis and recognized his new, destructive behaviors aligned with CTE.

During his most recent stay in treatment, it looked like Elijah was going to turn things around. But unfortunately, he left us on April 17, 2022 due to a heart attack, stemming from an enlarged heart. He was just 24. Based on everything I learned before his death, I made the decision to donate his brain for CTE research at the UNITE Brain Bank and am currently awaiting the results.

Elijah is my son. I speak of him in the present because he will always be my beautiful, sweet boy. I was there for the two most important moments of his life – the day he was born and the day he transitioned. I worry I will forget his face, forget what his voice sounds like and forget the powerful force he was on the lacrosse and football fields. I worry he will be forgotten by all who encountered him.

I want more minorities to be properly informed and educated about the impact of too many concussions early in life. I know parents may believe their child’s success is the only way to make it out of their circumstances. But it is unfair to look for the child to save his family at the cost of their brain and, in my son’s case, their life.

Some parents may not want to tell all of this information to the world. It might make them feel like they are ruining their child’s image. But I don’t share that feeling. I know Elijah and he would want to selflessly give to somebody else if it meant he could save their life. I am telling Elijah’s story to help parents make informed decisions about their children’s future. Unfortunately, it took Elijah’s experience to change my perspective on what sports kids should play. Elijah’s two younger brothers did not and will not play contact sports.

Football is great but it is crucial to know the many risks of playing the sport, especially before a certain age. My son was unrecognizable at the end; I didn’t even know who he was. You don’t want to have a memorial wall of all his trophies and accomplishments and not have him.

Yes, children need to play sports to stay out of trouble. But I challenge all parents to find a healthier way to keep their children productive – whether it’s safer sports like flag football, or other activities like coding. Please think of the long-term and consider how their life will turn out in the future.