Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Tenacious: not readily relinquishing a position, principle, or course of action; determined.

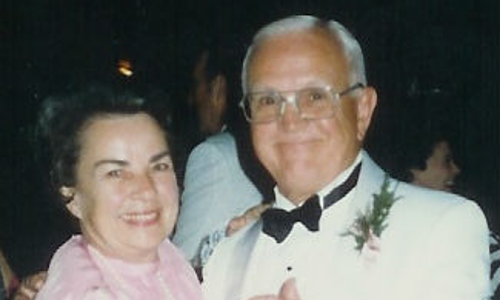

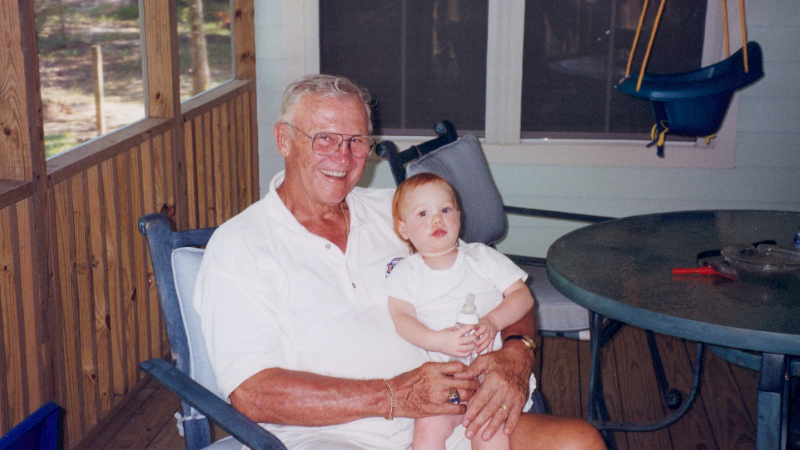

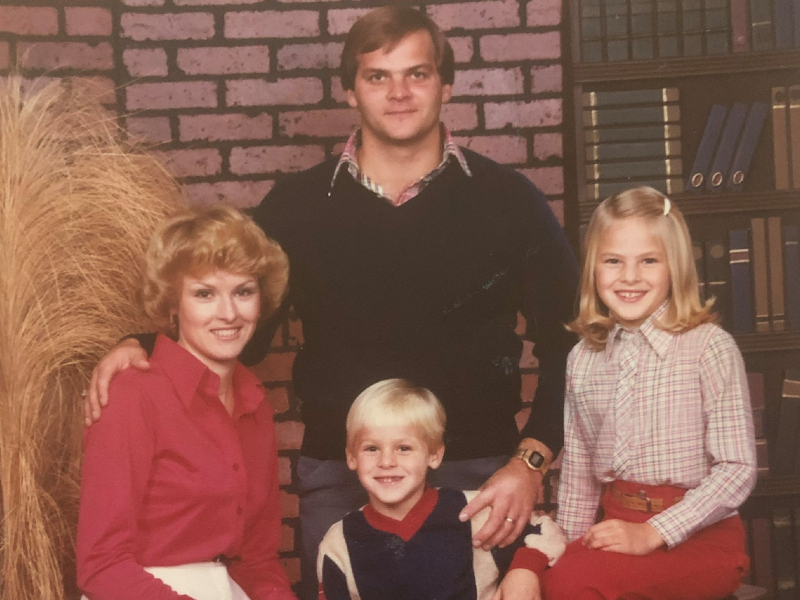

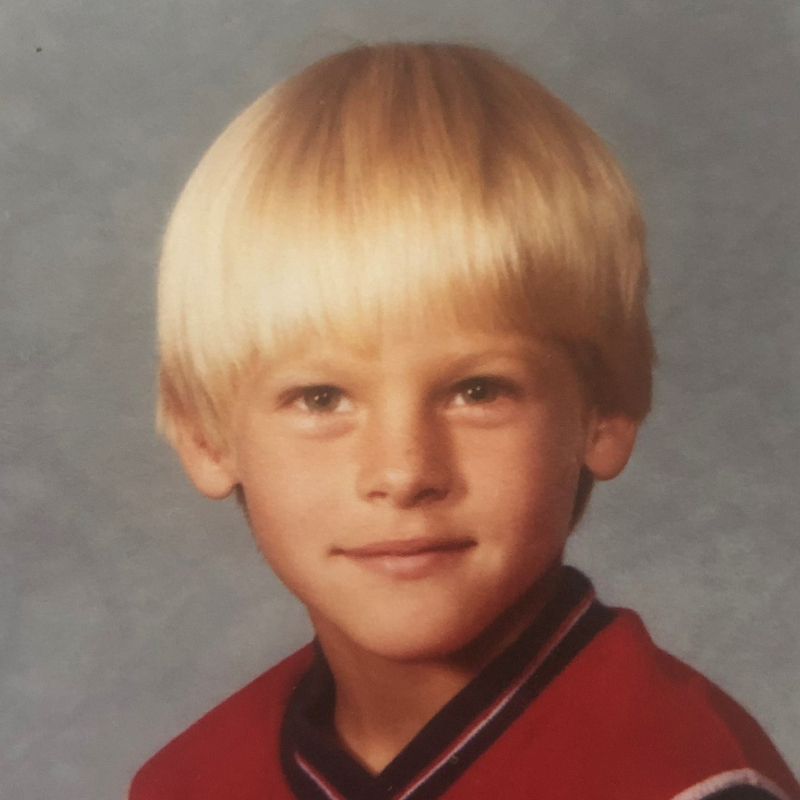

My brother Scott was nothing if not tenacious. It’s the word my mom used most, when describing his personality. Determined for sure, and always with an ornery little twinkle in his eye!

As a small child Scott was an early walker and then an early climber – of all things. When he was only two years old, he was caught halfway up a light pole during one of our dad’s slow-pitch softball games. The umpire stopped the game and asked whose kid was up there. Can you even imagine?

He also learned to ride his bike early, at just three and a half. He could ride it but couldn’t stop. A problem he solved by simply putting his feet down, which is why he always had bruises on the back of his calves… from the bike pedals hitting them each time he “stopped.”

Scott had lots of energy as a child. Our mom had him tested for ADHD because of his hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention. During his testing though, he was perfectly behaved and played nicely with his toy cars the entire time. Almost as if he knew exactly what to do to get out of the appointment. Since we didn’t have the information or help back then that we now have for these types of disorders, my brother was never officially diagnosed.

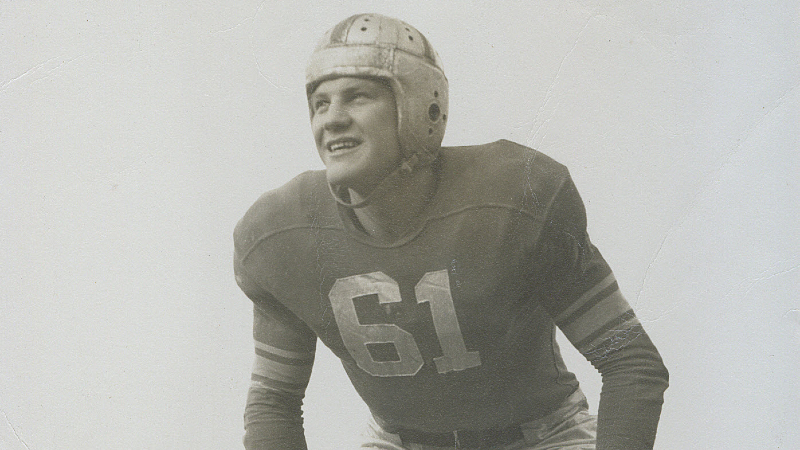

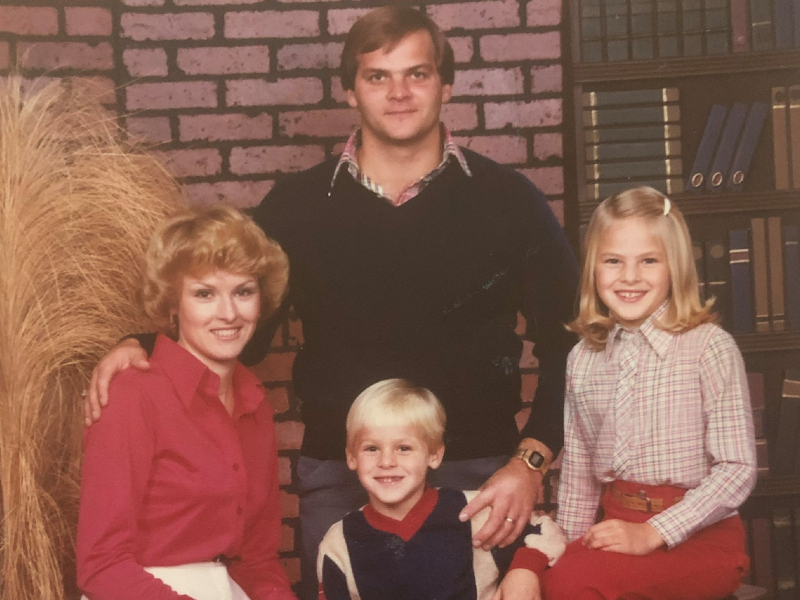

Scott was also very athletic, involved in several sports growing up. He started out playing baseball, like most young boys at that time. We moved from our small town of Oskaloosa, IA, to Des Moines, IA, before Scott’s 4th grade year. That fall he started flag football with our dad as his coach. He found his sport of choice! He would also try out wrestling and track along the way, but football was his constant, his passion.

He progressed to playing tackle football in 6th grade. We just didn’t know then; all we know now.

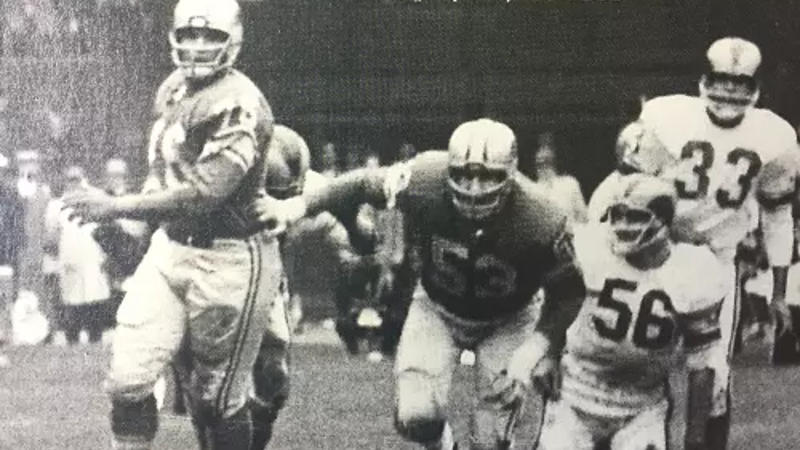

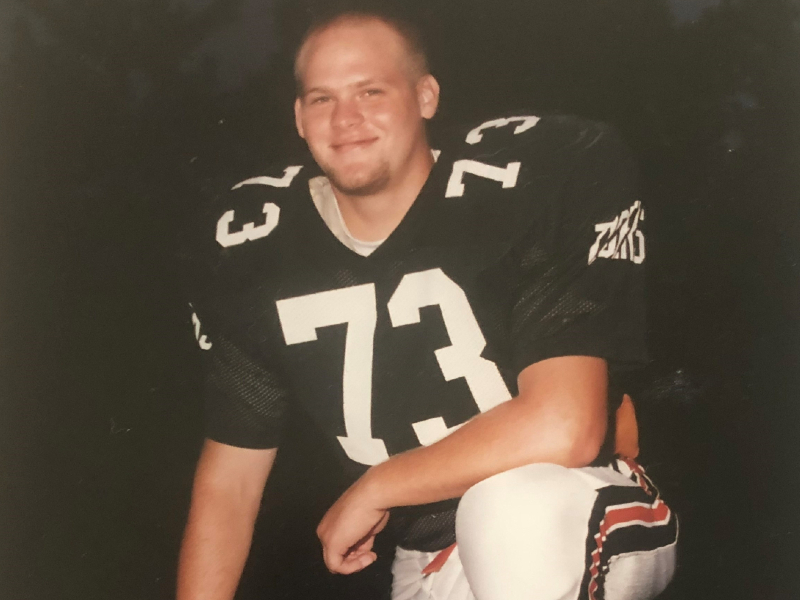

Scott played tackle football for the Des Moines Catholic League from grades 6-8. He then played four years for his high school team, the West Des Moines Valley Tigers. He made varsity from grades 10-12, making 1st Team All-State Defense as a senior. There were never any reported concussions during those years, but Scott played hard, giving 100 percent on the field and at practice. He loved the sound of helmets cracking, loved “hitting hard.” Again, we simply didn’t have the knowledge in the early ‘90s that we have now. If only we’d known.

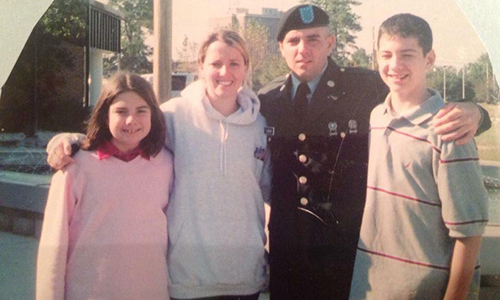

After giving college a try for one semester, Scott decided to enlist in the Marine Corps. He did so without much discussion with our parents, typical of him because he could be very impulsive. I think he also liked the idea of being a Marine and what they stand for: honor, courage, and commitment. He saw them as the best and the strongest of all the lines of service.

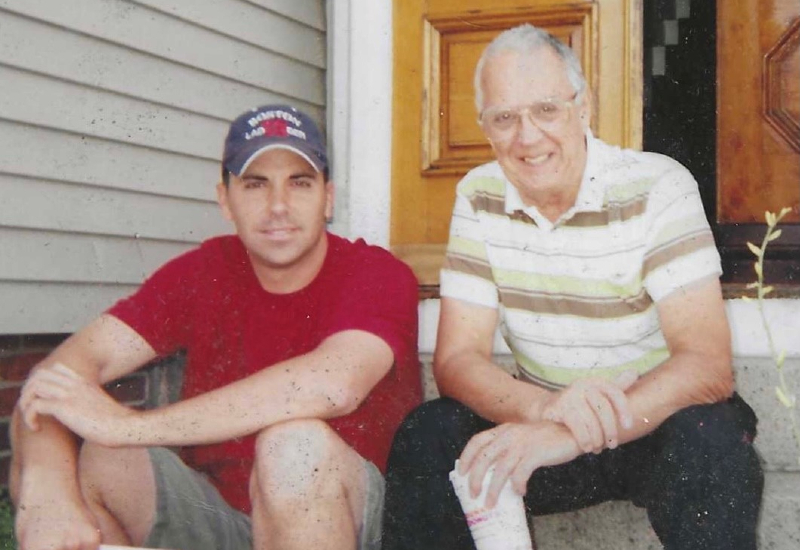

Our dad recalls Scott’s four years in the Marines:

“Scott enlisted in the Marine Corps in December of 1994. He went to basic training in San Diego at the MCRD for three months. While in bootcamp he was exposed to many instances of blows to the head and entire body during self-defense and combat training.”

His permanent station was at Camp Pendleton in California. His MOS was a TOW rocket operator (tank assault team) which obviously included being around explosions, concussive blasts, and other explosives.

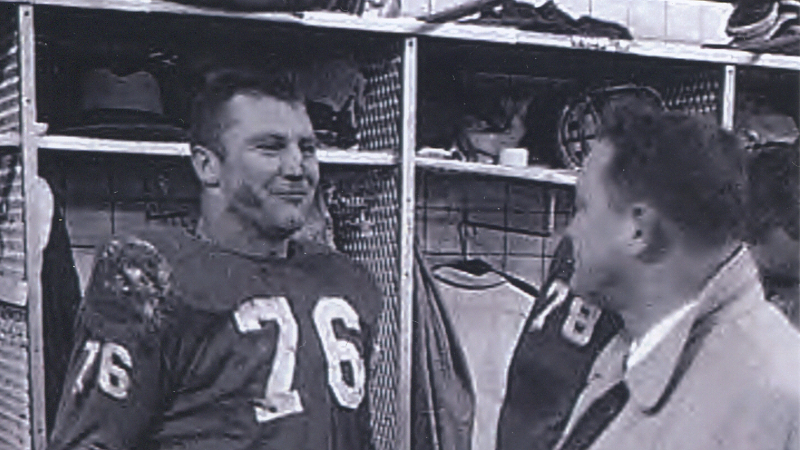

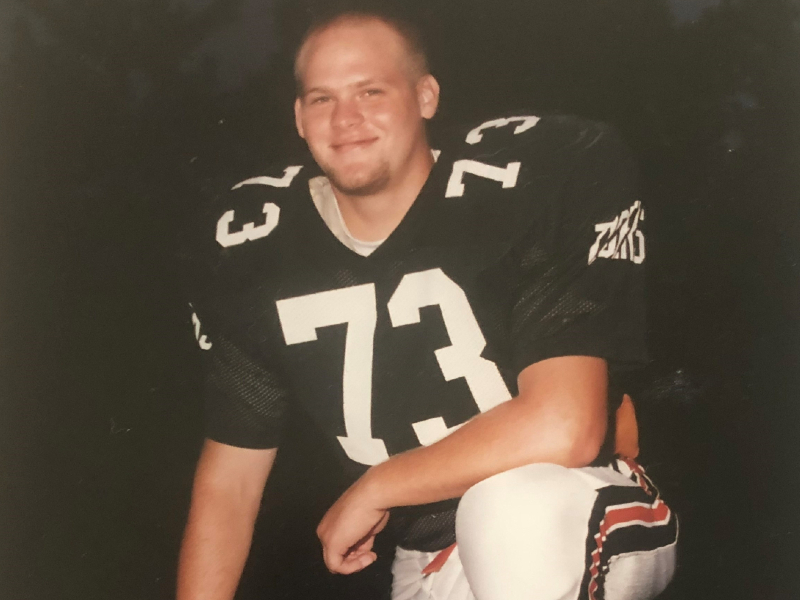

Scott was recruited to be a member of the Marine Regiment football team. He played three years and made All Base team twice. I would compare the level of competition to be similar to NCAA Division II but in much more “aggressive manner.”

I know for a brief period he and some teammates were using PEDs, obtained from across the border in Mexico.

Scott was the victim of an attack by another Marine while on duty in Arizona, patrolling the border. The fellow Marine struck Scott in the back of the head with a lead pipe. He spent at least one night in the hospital after this attack.

My brother completed his four years in the Marines and returned home to Des Moines in late 1998.

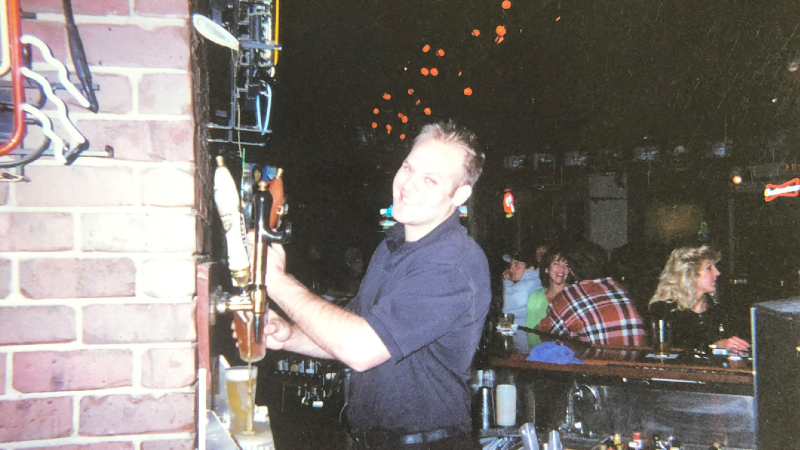

He returned to school at our local community college the following spring, then got married a year later. It was during this time Scott started to struggle with alcohol. He had been drinking since high school, but this is when we all saw the abuse begin. In hindsight, I think this might also be when he started to “self-medicate” with drinking, for reasons we still didn’t understand.

Scott was larger than life, a big personality who loved to have a good time. But he could be having fun and suddenly get pretty loud and opinionated, which sometimes got him into trouble.

One of those times was in the spring of 2001. He was out with friends and had had way too much to drink. He ended up in an altercation when leaving the bar. He was pulled out of his car and beat over the head with a Maglite by three attackers. He was beaten to the point where he was unconscious. The first responders on the scene told police that they didn’t expect him to make it. Scott spent two nights in the hospital, the first in the ICU with severe brain swelling. He clearly had a concussion from this incident, but to all of our recollections he didn’t do any sort of therapy to help with his recovery. Another example of, “if only we had known…”

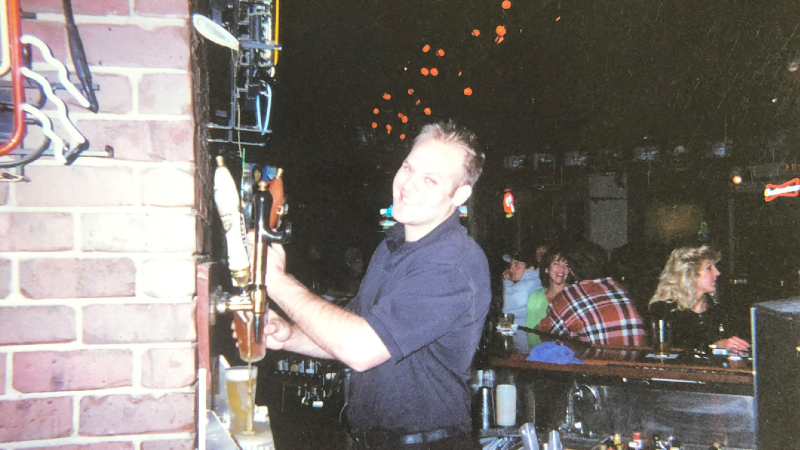

Scott got divorced shortly after. Fast forward to the summer of 2004 and he was still struggling with alcohol, having also gotten at least two DUIs by this point. He was working as a bartender at a popular neighborhood bar and attending classes at Grand View College to complete his degree. Despite the setbacks he experienced with his excessive drinking, life was good, and he was having a great time.

Scott also met who would become his second wife that summer. They had a lot of fun together and dated intermittently for several years, before marrying in 2010.

His ex-wife has said, “His goal was always to make others laugh.” When they were first dating though, my brother was convicted of yet another DUI which resulted in him being sentenced to a work release facility for almost a year. It was during this time he picked up running, to pass the time. His ex-wife remembers:

“He was incredibly determined and needed something positive to pour his energy into. Given his athletic abilities, he was a natural runner. He started signing up for half marathons, marathons and eventually took on triathlons and then an Ironman. Scott’s desire to beat others and his own personal times kept him motivated throughout the years. He always needed a goal. His race accomplishments made him seem supernatural!”

She also said, “Scott’s competitive drive is the reason I also started running and eventually signed up for my first half marathon. He helped me realize I could do it. He saw a drive in me I never knew existed.”

I love that memory of Scott – of him being able to inspire his ex-wife to become something greater than she even realized she could be. One of his longtime high school friends shared a similar feeling about him:

“Scott was an encourager. Sometimes bad, but I would never have started running without him. I still hear his voice late in a workout or when things get physically hard saying, ’Don’t give up, let’s go!’ A lot of my best finish times came from fear of being chased down by Scott late in a race. Once I could get out in front of him, I did not want to hear him say something as he was passing me. And you know he would always have a smart remark!”

Scott and his ex-wife had a daughter in 2014, then divorced a little over a year later in 2015. She said, “During our time together, Scott drank too much. He hid bottles throughout our house. He said he had a hard time falling asleep, so he’d take Benadryl late at night to help. We fought about that, and the drinking, a lot. Eventually, I couldn’t live with it anymore.”

Over the next five years, they tried to be a family again a couple different times but just could never make it work. It often had to do with his alcohol addiction and major mood swings.

My brother, my beautiful, beautiful brother. He was struggling more than any of us knew. Again, if only…

During the summer of 2016, I remember my parents threw out the idea that Scott was possibly suffering from CTE, in response to some erratic behavior he was exhibiting. I completely blew it off, scoffed even, that they were simply making excuses for his bad behavior. After all, he hadn’t played football in 20 years! I wrongly assumed (did not take the time to inform myself) CTE could only happen to football players, and it showed up shortly after they were done playing. I could not have been more wrong.

From 2015-2020, Scott competed in countless races. Running was his other addiction. He loved the challenge that triathlons gave him but running was his passion. He was an incredible runner. So fast. He participated in our local IMT Des Moines Marathon every fall and was able to qualify for the Boston Marathon with a qualifying time of 3:07. He then ran Boston in 2015, finishing in 3:30. That year, the weather was especially bad. It was cold, rainy, and windy. Brutal conditions for my brother, who was an absolute lover of the heat.

Something I haven’t mentioned is that Scott was also an avid smoker. I know, an incredible athlete who treated his body like a temple when it came to exercising and the food and supplements he put into it, but yet he could drink like a fish and smoked too! One of the things that drove me crazy about him was how, after a race, he would immediately pull out a cigarette and light it up. Right in the middle of the crowd of runners who were likely not interested in inhaling his secondhand smoke. Back to his run in Boston; I was scrolling through his race pictures online, after he passed, which was a very bittersweet experience. I came across a string of three or four and couldn’t believe what I was seeing. He had stopped during the race, lit a cigarette, and then was running while smoking. Clearly, he had had it with the weather and the race! Such a funny moment, one I wished I’d known about prior to him dying, so I could razz him about it.

Scott’s biggest race accomplishment would undoubtedly be his Ironman. He did Ironman Wisconsin in September of 2018. Scott got his last DUI in April of 2017. Long story short, he ended up with an ankle device for a year, was not allowed to drink for that next year or he would go to jail. Scott poured all his energy into getting healthy and training for and then completing that Ironman.

Sadly, once the ankle device came off, he started drinking again. He thought he could handle it, control it. A game so many addicts play.

He continued to run in races, up until the world shut down in March of 2020. I think he was supposed to participate in our local St. Patrick’s Day run that March, but was unable to after its cancellation.

Scott’s drinking was getting out of control, though none of us fully understood how bad it was. So many who knew him, who loved him, have said, “if only he could have had his races, maybe they would have provided the focus he needed…”

In 2020, Scott would have done the following races, because he had done them for countless years before: Drake full or half marathon in April, DAM to DSM in June, then he would have been training for the IMT Marathon in October.

The world had shut down though and all runs had become virtual. He didn’t have his running community, the connection he desperately needed.

Another one of his longtime high school friends wrote this:

“Scott was a true friend. I thought I knew most of what was going on in his life. There were certainly a few flaws (which we all have), but things on the outside seemed to be just fine. His story is a good reminder to dig deeper to make sure your friends are okay, and to make sure they know to call if they need someone. Scott’s one of a kind, a hilarious super athlete who was always down for a great time. I think about him every day, and am really sad we could not give him what he needed in the end.”

I wish more than anything that we could go back, help Scott, save him. If only we had known then, what we know now.

When I look back, things really started to unravel for Scott the last eight weeks of his life. But in actuality, it probably started happening many months before that. Our dad’s thoughts on this:

“Scott’s patience and mood changed slowly the last year or so leading up to his death. He dramatically became more negative and there were many incidences of Scott quickly losing his temper, having seemingly unprovoked outbursts. He knew something was wrong with his thinking and ability to control his temper. We talked about it, and he decided to see what could be determined by seeking medical help. Unfortunately, he never made it to that appointment.”

The appointment our dad refers to was one at our local VA. It was an appointment to see if Scott was suffering from a TBI, or traumatic brain injury. His appointment was scheduled for October 7, 2020. He never made it because he died by suicide on September 18, 2020.

Some of my recollections during those last several weeks: My brother was upset about his ex-wife meeting someone new. He apparently thought they still had a chance at getting back together, becoming a family again. He started calling her incessantly, made a verbal threat of harm towards her new boyfriend, just a couple examples of his erratic behavior. She took legal action and had a no contact order, and then a restraining order, filed against Scott. We fully supported her. All of this, along with the fact we didn’t fully understand how depressed Scott was, how out of control his drinking had become, or how to get him the help he desperately needed, led to his first suicide attempt on September 7, 2020.

As I sat with him in the hospital that night, he told me he was tired of being a burden. It broke my heart. He was absolutely not a burden to anyone. Was he scaring all of us? Yes, absolutely. His behavior was out of control. He was out of control. He also told me something was wrong with his head and he was going to have a TBI study done soon. At the time, I had never heard of a TBI. When he explained to me what it meant, I told him he just needed to stop drinking and get on the right antidepressant. He had a brain injury, was literally losing his mind, but I simplified it as, “just stop drinking and get on the right meds…” If I’d only had the information then that I have now.

My brother was released from the hospital the next morning and then arrested the same afternoon for breaking the no contact order. When he attempted that first suicide, he had done it on his ex-wife’s front steps. How much that scared her, I will never know. I am certain Scott’s intention wasn’t to scare or hurt anyone. Yet, that’s exactly what he was doing, scaring all of us.

He spent four nights in jail. Our dad bailed him out on Saturday morning. He came over to my house and had dinner with us. There were lots of tears and honest conversations, lots of hugs too. He felt so bad about what he had done, how he might not get to see his little girl for a long time due to his actions. He seemed to be in the right head space though, seemed to “get it” and wanted to take the steps to be better, and get better.

As the week went on, he started to get more and more agitated. We were texting a lot throughout the day each day. He came over for dinner again on Wednesday night. Looking back, he had been drinking. He wasn’t supposed to be drinking and I didn’t think (at the time) he was. As he was leaving we stood outside and talked for probably 30 minutes. The conversation was one I had a hard time following. Scott was so upset again, angry, and not making a lot of sense. At one point he was tapping the back of his head, saying, “I know there’s something wrong with my brain!” I was trying to talk him down, but he left mad. I wish so much I could go back to that night and just hug him, hold him, and tell him I love him, that it would all be OK.

I talked to our dad the following evening, explaining how I didn’t think Scott was doing very well, and seemed really agitated again. We agreed we needed to take steps to help him. The next morning our dad called and spoke to Scott’s therapist about our concerns. Scott then had a virtual appointment with her, where she shared our worries with him. He texted me after saying he shouldn’t have shared so much. I said no, he should definitely share, just not threaten harm. I explained we were all so worried because of how erratic his behavior had been lately, and if he hurt the boyfriend, he would effectively end his life as he knew it, meaning he would go back to jail. His response was, “Don’t worry, I won’t hurt him.” I will forever regret not responding with, “Don’t hurt yourself either,” but I didn’t. We texted a bit more, about how he was going to come over in the morning to go on a 50-mile bike ride with my husband. My husband was training for his first half Ironman and Scott was going to ride with him. A ride that never happened.

Approximately three hours after our last text, my brother would die by suicide. He had driven by his ex-wife’s house, breaking the restraining order. The police came to arrest him again. My dad called Scott, explained they were on their way and told him to comply. Scott pulled a pellet gun on the officers. It wasn’t a gun that could do real harm, but it looked like a real gun. Scott purchased it during quarantine for target practice to get him out of the house. Having been a Marine, he had a lot of respect for authority and would never hurt a police officer. They had no choice but to shoot him though. It’s what my brother was counting on, for them to end his suffering.

The morning after Scott died, our dad called the medical examiner, asking him to please have Scott’s brain tested for CTE. Due to the manner of his death, we were only able to send the UNITE Brain Bank small samples of tissue from Scott’s brain. It often takes close to a year to get the test results back. We got the results back on October 11, 2021. It was confirmed, tau protein was found, which is consistent with early-stage CTE, but the researchers needed the whole brain to get an official diagnosis. Still, the study provided so much validation because Scott knew something was wrong with his brain.

I am sharing Scott’s story, so many details of his story, because I hope (we hope) it will help someone. If someone can read this, recognize these symptoms in their loved one, and help them, then his death won’t be in vain. I urge all parents to consider programs like Flag Football Under 14 to prevent unnecessary repetitive head impacts when children are too young. I don’t want another family to have to live with the “what if” and “if only” we live with. If only I had known what CTE really was, if only I had seen CLF’s website and social media page sooner, where you can read about the signs and symptoms of CTE.

On October 28, about six weeks after Scott died, I came across a post a friend had made on Instagram. It was a post about a charity event for CLF, the Concussion Legacy Foundation. I clicked the link and started reading, then started crying. I saw the post which listed the signs and symptoms of CTE. It was all there, and it was all so clear: THIS is what my brother had been suffering from. And there was a Helpline. A Helpline?! What if I had seen that Helpline?

What if I had seen it six weeks before Scott died, instead of six weeks after? What if? If only..

To my beautiful, beautiful brother: You were loved. Loved SO much. You were worthy. Worthy of a GOOD life, free of the pain you were suffering from. And you were never, EVER, a burden.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.