Most athletes can only dream of reaching the pinnacle in just one sport, let alone two. Ollie Matson was not like most athletes, however. Not only is he a member of both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame, he also won two Olympic medals with the U.S. Olympic track and field team in 1952.

Matson started playing football as a freshman at George Washington High School in San Francisco before joining the University of San Francisco Dons as a star two-way player. He was a 1951 Heisman Trophy finalist following his senior season, when he led the country in both rushing yards and touchdowns. While Matson finished ninth in Heisman voting, his performance led the Chicago Cardinals to select him third overall in the 1952 NFL Draft. Matson went on to play 14 seasons for the Cardinals, Rams, Lions, and Eagles. Throughout his career, Matson was a six-time Pro Bowler, and his 12,799 career all-purpose yards at the time of his retirement ranked second all-time only to Jim Brown. Matson is a member of the NFL 1950s All-Decade Team and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1972 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1976.

Upon retiring from football, Matson joined the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as its director of special events, where he remained until retirement in 1989. Outside of work, Matson dedicated his life to others. He was a passionate volunteer who spent much of his free time mentoring children, especially those in juvenile hall and corrections. Matson also served as a football coach for nearby Los Angeles High School.

But family always came first and foremost.

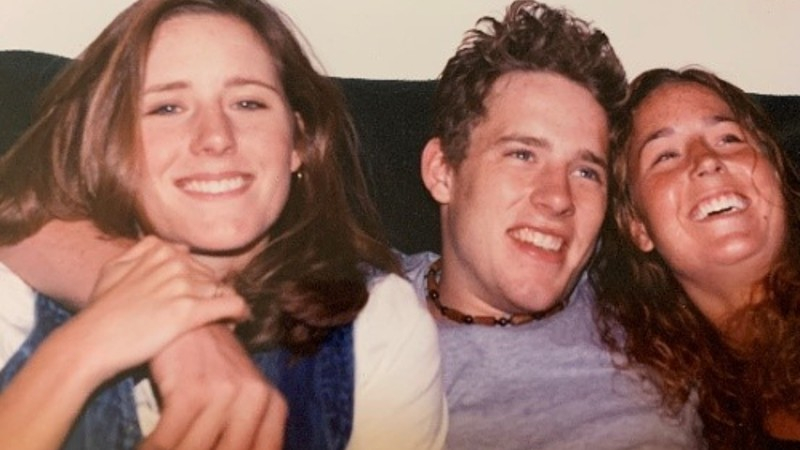

“My grandfather was a gentle giant, soft-spoken and disciplined,” said Matson’s granddaughter Lara Parker. “He made sure to spend time with all of his children and grandchildren, even though they were scattered throughout the country.”

In addition to being with family, Matson followed a strict daily routine of his favorite activities, including cooking and gardening. He stayed active by walking every day from his home to L.A. High School and back. He also loved watching horse racing but had to stop when his memory began to worsen, as he would forget how to return home from the track.

Once Lara graduated from college, she moved back to Los Angeles to help take care of her grandfather, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. As the only person around him full-time, Lara was able to see his changes firsthand. Though Matson never talked about the injuries he sustained while playing football, his wife and twin sister often commented on the amount of hits he took. There were occasions he stayed in bed for days with a headache, only to take the field again as if nothing happened. One particular college game comes to mind: a 1951 matchup against the University of Tulsa. Matson was specifically targeted and hit by the other team for being a Black player.

The always determined Matson slowly started acting in unrecognizable ways, becoming almost childlike at times. Once he reached his 70s, he could no longer drive and did not have the capacity to stay active. There were moments he would forget how to do simple tasks like taking a shower. Matson would get down to play with his grandchildren, but not have the strength to get back up. And though he remained stubborn, he fortunately was never aggressive or physical around people. While Matson’s family originally attributed his decline to Alzheimer’s and old age, they sensed something else more serious might be in play, as news about former football players diagnosed with CTE became widespread.

After Matson’s death in February 2011 at the age of 80, his family made the decision to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) CTE and noted it was one of the most severe cases they had seen at that time. In fact, they were shocked he was able to survive so long in his condition.

“We discussed the donation before his death, suspecting he was in the end stage of CTE,” said Lara. “The hope was to help future families from suffering like we did.”

Though the Matson family wasn’t surprised by the diagnosis, they were startled by the severity. Because Matson mostly kept everything to himself, they didn’t know how much he was struggling.

“He must have known something was wrong but couldn’t express it,” said Lara. “Was he depressed? Sad? Frustrated? It’s painful to know the strongest person you know was suffering internally and we couldn’t help.”

Lara and the rest of the Matson family want other families who may be in a similar situation to learn from their experience. They are strong supporters of CLF’s Stop Hitting Kids in the Head campaign, which aims to convince sports to eliminate repetitive head impacts under the age of 14 to prevent future cases of CTE. She urges other parents to reevaluate their young children’s involvement in contact sports and the potential risks of pursuing this path.

“Ultimately, we want Ollie’s donation to help further this crucial research so we can truly understand the impact of concussions and related traumatic brain injuries,” said Lara. “We also want others to know no matter how bad something may seem, you’re not alone, and there is a strong network of other families like ours who understand.”