John Hilton

Glen Ray Hines

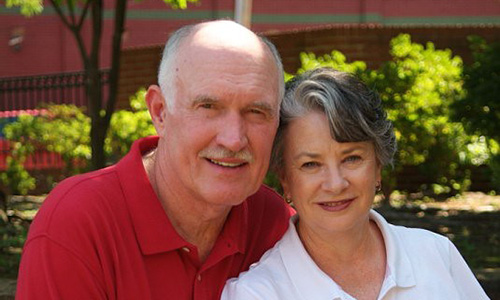

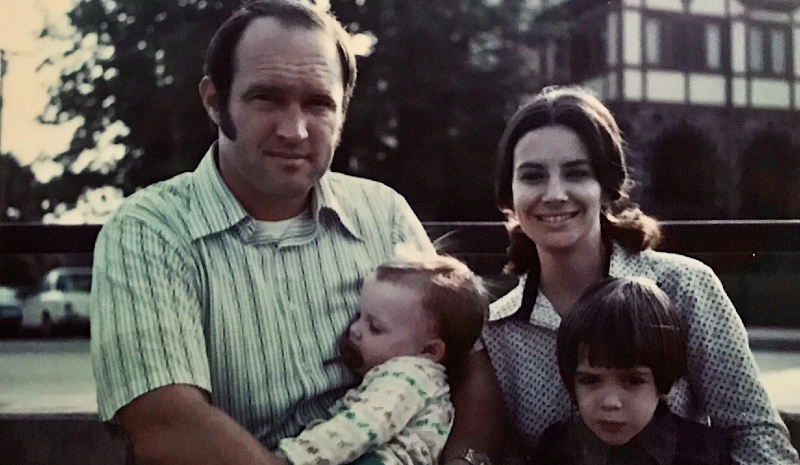

My father Glen Ray Hines was born October 26, 1943, in El Dorado, Arkansas. He graduated from El Dorado High School in 1961, and attended the University of Arkansas from 1961-1965. He and his family lived primarily in the Houston, Texas area, where myself, my brother Wes and sister Sheila were born, before he and our mother moved to the northwest Arkansas area.

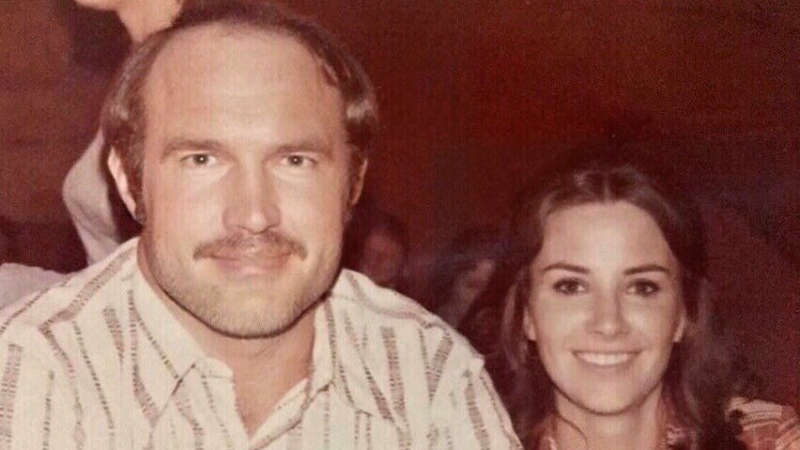

Above all things in his life, Dad loved his wife, children, and grandchildren. He met our mother Jody, his high school sweetheart, in their teens and they married in 1965. Dad was first and foremost a family man. He took an avid interest in his children’s education and extracurricular activities, but the event he was most proud of in our lives was our individual acceptance of Jesus Christ as our personal Lord and Savior.

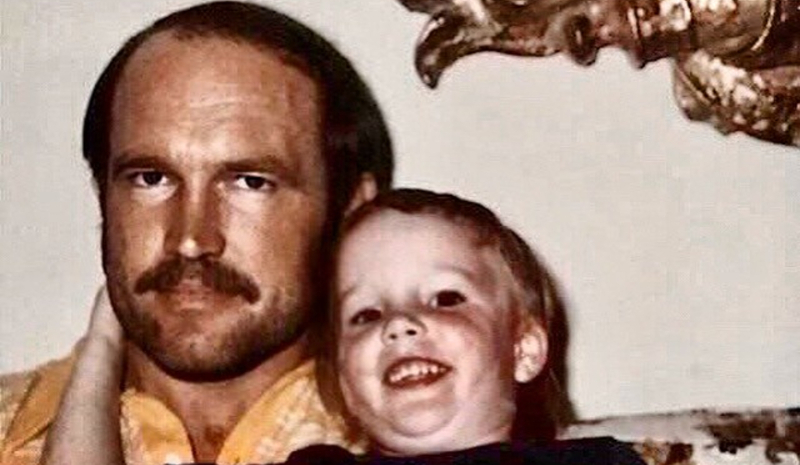

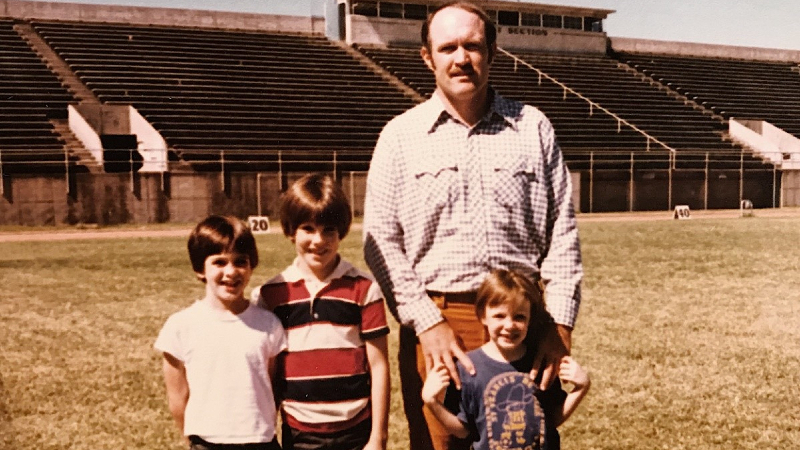

I’ve often told people that Dad was a big man, but he cast a very small shadow. He was a quiet man who preferred action over words. The most humble man his children ever knew, he would much rather speak with you about the latest accomplishments of his children or grandchildren than anything he had accomplished himself. I’ve never known another man to spend more time, quality and quantity, with his children. During our formative years, he was completely and totally invested in everything in our lives, and if you asked him, he – in a rare moment of being prideful – would tell you this investment paid off. After his children were grown with families of their own, he took a keen interest in his grandchildren’s lives, always asking about their education and activities, and in his later years, he enjoyed nothing more than attending their athletic and scholastic events.

Indeed, our father was his children’s hero, but not because of anything he did on an athletic field. That was a small, finite period of his life. He played football for only 15 years. He lived for another 60. It was what he did during the other 60 that mattered, at least to his family. It was what he did in those other 60 years that bore fruit. It was an investment that paid off.

As much as I might want to overlook it, we must admit football was, without question, a significant part of his life. It affected his life as well as ours, in many different and conflicting ways. As much as football impacted his life, he in turn, left his own, influential mark on the history of Arkansas Razorback and Houston Oiler football.

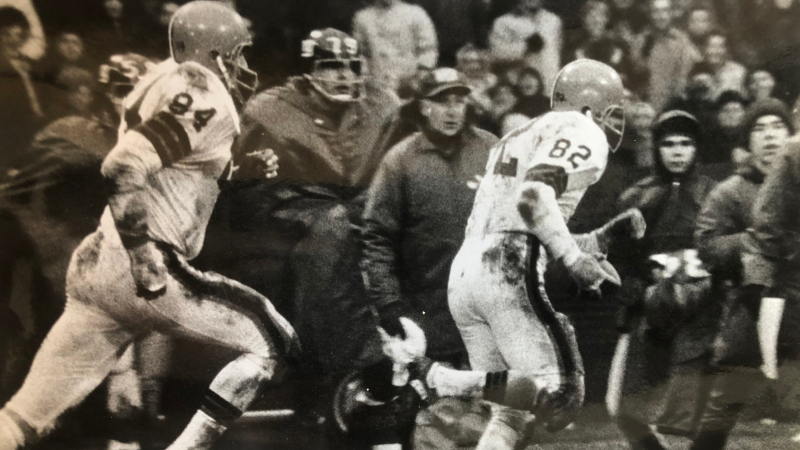

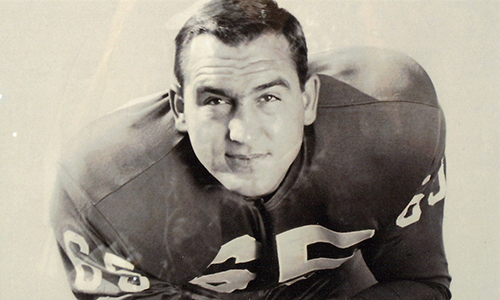

A two-sport standout at El Dorado High School in Arkansas, he played collegiately for the University of Arkansas Razorbacks from 1961 to 1965. In 1964, he was the anchor of an offensive line that helped Arkansas win its only National Championship in football, and in 1965, he was a consensus All-American. The Houston Post named him the Southwest Conference’s Most Outstanding Player for the 1965 season, a rare honor for a lineman. In 1989, Dad was named as one of the best two offensive tackles of all-time in the 82-year history of the Southwest Conference when he was named a member of the Express News San Antonio, All-Time Southwest Conference Football First-Team Offense. In 1994, he was selected as a member of the Arkansas Razorback All-Century team. He was inducted into the Razorback Sports Hall of Honor in 2001 and the Union County (Arkansas) Sports Hall of Fame in 2012. In October 2018, he was inducted into the Southwest Conference (SWC) Sports Hall of Fame.

In 1965, there were two professional football leagues, the NFL and the AFL, and Dad was drafted by both; the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals, and the AFL’s Houston Oilers. In 1966, he signed with the Oilers and played for Houston until 1970. He played the 1971-72 seasons with the New Orleans Saints, and retired after his final season with the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1973.

Dad was an accomplished pass blocker at a time when offensive linemen were severely restricted in the use of their hands to block pass rushers. He was an AFL All-Star game selection, the AFL version of the Pro Bowl, in 1968 and 1969. A model of durability, from his first season in 1966 through his final season in 1973, he started and played in 115 consecutive NFL games, including three playoff games. In December 2005, the Football Digest named him to the All-Time Houston Oilers Team.

But all this achievement and recognition that American society places so much value on, at least while football players are in the public eye, eventually came at a big price to my father and our family.

Shortly after he retired from the NFL in 1975 at the age of 32, Dad began to show some early symptoms that have become all too familiar to other football players and their families. When he was diagnosed many years later with serious neurological disease and probable Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), these symptoms started to make sense in hindsight, but at the time our family had no idea what to make of them. He was reclusive. He was always writing things down in notebooks, which he had countless numbers of around the house that he would keep long after they were completely filled. We didn’t know why. He experienced sudden fits of anger that seemed to be way out of proportion to the precipitating cause. He would close himself off from people. He went through dark moods that made him unapproachable. He had difficulty maintaining a job, although he was offered numerous opportunities. His explanation at the time was that the jobs took too much time away from being able to spend time with his family. But we suspected there were other issues at play that made it very difficult for him to maintain steady employment. He avoided attending any functions that required him to speak publicly and did not often attend reunions of his football teams. People concluded he was aloof, standoffish, and even arrogant. But they had no idea what was really going on.

He also suffered from an acute, palpable depression that no one could understand, least of all him. It debilitated him, and in turn, it debilitated our family. Our fellow “football families” who have been through these same experiences can understand this and how this insidious affliction affects not only our loved one – our father, our brother, our son – who played the game, but it also leaves a wide path of damage in its wake that impacts everyone who loves and cares about them.

When it started to manifest itself, Dad even wrote letters to his children attempting to explain what he was going through.

“I can’t explain what exactly happened to me,” he wrote. “Lately I’ve been having more and more doubts of whether I will ever get back on track. It seems like nothing ever works out for me, though I still consider myself the luckiest man in the world and I have much guilt about letting myself get down after I have been blessed with so much in life. However, I haven’t given up, and I will continue to try and make something positive happen with my life. As long as I can breathe, I have a chance.”

He was still a relatively young man when he wrote this, but he knew there was something wrong. The real miracle of our father during these years was the fact that he was so strong, he was somehow able to hide much of this and keep it under control for the most part; to live with it while at the same time knowing he had some kind of strange affliction that he couldn’t understand. This is why during his last days, most of his friends expressed shock that he had taken such a rapid physical and mental crash that he was in hospice care within the span of about two weeks. No one had any idea how bad his condition was, nor how long it had existed.

Later in life, his physical and cognitive decline became more rapid and advanced, and he was eventually diagnosed with advanced dementia that his doctors found resulted from his football career. He decided to donate his brain for analysis to the Boston University CTE Center. Almost one year after his death, in January, 2020, the Boston University CTE Center diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE, the most advanced and severe form of CTE. There was “global spread” of the disease to every part of his brain and even in deeper parts of the brain rarely observed in other cases.

But football and his CTE diagnosis are not his legacy.

Despite what football did to him, he was still able to overcome it, until nearly the very end. With perseverance, he ran the race marked out for him, and he won.

His legacy is that he was an example. He was an outstanding role model for his children. He was the example of what a Christian husband should be. He was the example of a good Christian father and grandfather. He was the example of a humble Christian servant. And he was an example of a good and loyal friend.

This is the legacy he gifted us. And these are the things we will remember.

We are very thankful to the incredible staff at the Boston University CTE Center and the Concussion Legacy Foundation, especially Lisa McHale and Dr. Thor Stein, for their dedication and hard work, and the professionalism they exhibited from the first hours after Dad passed away through the long wait to find out the results of his testing.

Michael Hoban

Paul Hornung

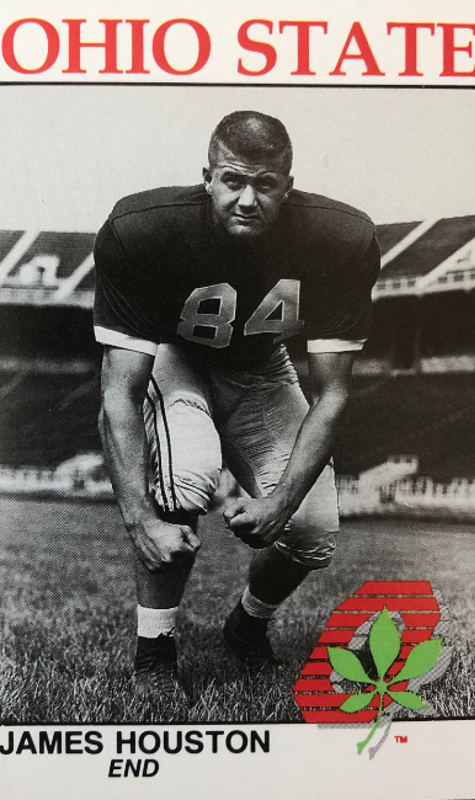

Jim Houston

Mr. Dependable

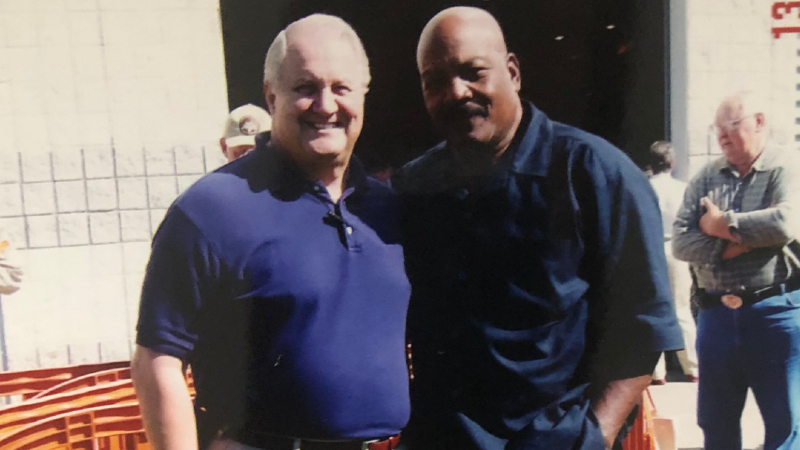

At lunchtime in Massillon, Ohio, a young Jim Houston would run home from school to snag food. Then he’d run back. In an age before sparkling weight rooms for football teams, Houston had to squeeze in exercise any way he could. The team needed him, of course.

Houston started playing football in the eighth grade. He tried out for the team the prior year, the first age kids could start playing in Massillon, but he was deemed too small. Two years later, Houston earned All-City honors as a tackle and defensive end for Massillon Washington High School. He led Massillon Washington to a state championship in 1953.

His exploits in high school garnered the attention of Woody Hayes, then coach for The Ohio State University. Houston’s older brother Lin had starred for the Buckeyes in the 1940’s. Hayes recruited Houston to play defensive end and convinced Houston to relocate 118 miles south along Interstate 71 to Columbus and play for the Buckeyes. There, Houston’s habitual winning continued.

Freshmen weren’t allowed to play varsity football when Houston arrived on campus. Still, coaches saw his potential and heavily involved him in film sessions and practices in preparation for a big role his sophomore season. In that 1957 season, Houston started on offense and defense including catching an interception and playing all 60 minutes in the Rose Bowl to help the Buckeyes win a National Championship.

Houston continued to play both ways his junior and senior seasons, before being selected in the first rounds of both the 1960 AFL and NFL Drafts. He again followed Lin by opting to play for the Cleveland Browns.

Houston played defensive end for his first three seasons with the Browns, but setting the edge wasn’t his only obligation. In 1962 and 1963, Houston served as an infantry unit commander for the U.S. Army spending his weekdays at Fort Dix, New Jersey. On the weekends, Houston flew to wherever the Browns were playing. His commitment to his country and his NFL team earned him the nickname “Mr. Dependable.”

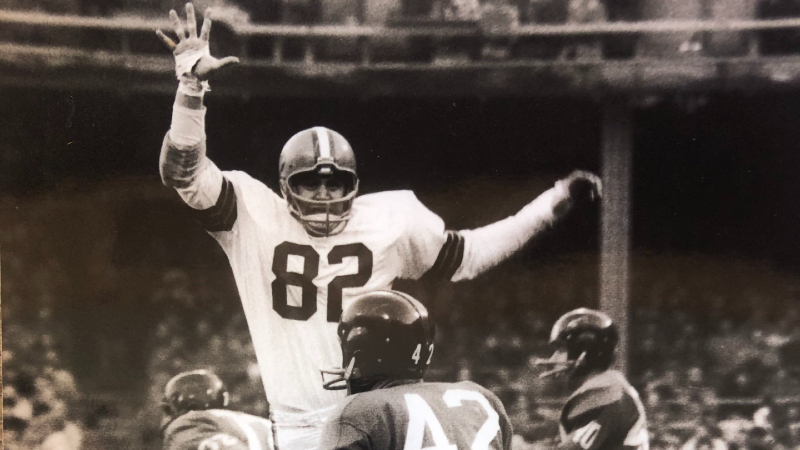

The 1963 season brought change and success. The Browns hired Blanton Collier as head coach, who moved Houston from end to linebacker. The following season, Houston made the Pro Bowl and the Browns found themselves in the NFL Championship against the Baltimore Colts.

The Colts were favored heading into the game, but the Houston-led defense shut out the high-powered Colts offense in a 27-0 win. Houston covered Baltimore tight end John Mackey in single coverage and held the future Hall of Famer to one catch for two yards.

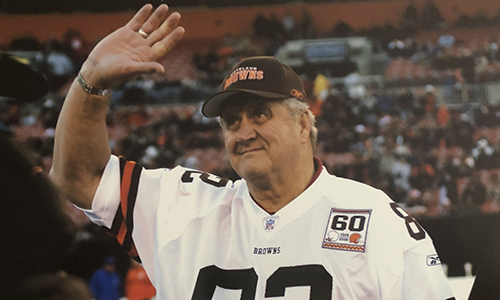

Houston made three more Pro Bowls in his career while moving to whichever linebacker spot the Browns needed him. He retired from the NFL in 1972 and was inducted into The Ohio State University Varsity “O” Hall of Fame in 1979, the College Football Hall of Fame in 2005, and the Browns Legends in 2006.

His career was not without pain, as Houston suffered several concussions. His most public came in a 1969 playoff game against the Minnesota Vikings, led by quarterback Joe Kapp. While trying to chase Kapp, Houston’s helmet hit Kapp’s knee pad and knocked him out. The Browns lost the game 27-7, and Houston was delirious for weeks afterwards. He had trouble driving and couldn’t go to work.

Houston’s concussion history predated his NFL days. During one of his many speeches for charity causes, he recounted being knocked out on the opening kickoff of the Ohio North-South all-star game, and then re-entering the game in the second half. “There was no holding me back after I regained consciousness,” Houston said. “By that time, it was in the second half.”

Life after football

Jim Houston’s post-football life was colored by charitable ventures, most often to give back to the youth of Ohio.

Houston’s dedication to the next generation started early. He frequented the Boys and Girls Club of Massillon as a kid and led fundraising efforts to give back to the clubs of Ohio. In 1964, a 15-year-old Akron boy who had just lost his father wrote to Houston for advice. Houston wrote back as he did with all fan mail. He penned, “When you come to the point where you can’t take one more step, take two.”

After he and his first wife divorced, Houston moved to Bainbridge, Ohio in the early 1990’s. He started attending the United Methodist Church in Chagrin Falls.

“He never said anything about being a former player or anything,” said Donna Houston. “Finally, someone in the congregation told me that he was the most eligible bachelor at the church and I should pay attention to him.”

Donna was a nurse in the area and noticed how Houston cared for his granddaughter. She would hear him say, “How ya doing, kid?” to the many churchgoers whose names he didn’t remember but whose presence he so appreciated.

They attended the same classes between first and second services and began to find common interests and beliefs. Donna and Jim started dating in 1997 and were married in 1998.

The Houston’s loved to travel, and they did it often. Aside from frequent trips to Columbus and Cleveland, they rented various timeshares. Their travels took them to southern mainstays like Myrtle Beach, Hilton Head, and Savannah. Donna and Jim fell in love with Savannah’s courtyards complete with fountains and vines. They installed their own Savannah-style courtyard in 2002, which became the site of many nights entertaining friends and peaceful mornings together.

Houston’s grandchildren adored him, and he adored them right back. Donna and Jim loved to babysit, and hosted the children for summers, and attended their sports games.

But around this time, Houston’s decision making began to alarm Donna. He made choices without any regard for consequences, especially financially. He gave telemarketers exactly what they wanted and spent money the Houstons didn’t have.

“It’s like you don’t have any common sense,” Donna would say to him.

“Just forget it”

Donna came to learn that Houston’s financial issues were set in motion years earlier. He declared bankruptcy before they got married.

His troubles began to extend beyond financial issues. By around 2006, his behavior was so bizarre Donna began to take notes. He once removed a lightbulb from a lamp and put it in a different lamp, then vehemently denied ever doing it.

“Just forget it,” Houston said to Donna in what became a phrase she heard far too often.

Donna always went to bed before Houston and would kiss him goodnight. Minutes later, Houston would ask Donna where his kiss was and assumed Donna was lying when she corrected him.

Houston could become angry and frustrated after these bouts of confusion, especially behind the wheel. He couldn’t believe there was a law that he had to slow down in a school zone. When driving became dangerous, Donna had to quit work to take care of Houston.

Donna received validation when one of Houston’s sons came to visit in 2006. After seeing his father struggle, he voiced his concerns to Donna.

“It was absolutely overwhelming,” said Donna. “I loved him so much. When he starts fading away from you, it felt like your heart was being ripped out. How could this be?”

Losing Jim

Donna and Jim knew there was a problem, and Donna began to connect the dots between Jim’s football career and his cognitive and physical decline. She clipped newspaper stories about the then-burgeoning link between NFL players and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Houston was primarily concerned his decline could be passed on to his children. In 2008, Houston jumped at the opportunity to have his brain studied for research. He began participating in the Boston University LEGEND study and participated in yearly questionnaires about his cognitive state.

Donna got plenty of advice to get help with Jim’s care. But her love for Jim, her nursing experience, and her desire to learn kept her going. She took a six-hour class from the Alzheimer’s Association about how to best take care of Jim. She made sure Jim got outside and stayed social. The two took daily trips to libraries and various metro parks in Cleveland.

Mobility also became an issue for Houston and therefore Donna. He was diagnosed with ALS in 2014 and visited the Cleveland Clinic’s ALS center. For Jim to go upstairs, she had to hold on to a gait belt to stabilize him to navigate the stairs.

One day, Jim and Donna tumbled down the stairs. Donna realized she was no longer able to care for Jim herself. She moved him in to a dementia living facility in June 2017.

Donna visited the facility every day to bathe and change Jim and spend time with him outside. Jim’s trademark spirit was still on display.

She still heard “How ya doing, kid?”

She noticed Jim, who had an enormous sweet tooth, give his cookie to a man who was worse off than he was.

She noticed his charm was still winning over other ladies at the facility, who overwhelmed him with attempts at kisses.

But she also noticed Jim’s affliction was different than his peers at the facility who were suffering from Alzheimer’s. While others couldn’t remember their own kin, Jim still knew who Donna and his kids were when they visited.

Named after Houston’s old Super Bowl foe John Mackey’s uniform number, the 88 Plan provided some respite for Donna and Jim. Mackey died in 2011 after a long battle with what was eventually diagnosed as CTE. His public struggle with the disease led to the 88 Plan to provide $88,000 a year for former players living with dementia. The 88 Plan paid for Jim’s care and for Donna to find community.

Twice a week, Donna went to support groups for dementia caregivers. She thanks those groups for helping her get through the idea that her husband was fading away.

On Tuesday, September 11, 2018, Jim Houston passed away at age 80.

Jim’s Legacy

After his death, Jim’s brain was sent to the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston. His spinal cord was supposed to also be studied for ALS research but complications from the coroner prevented it.

Dr. Russ Huber of the Brain Bank informed Donna of the test results. Houston was diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE. All signs pointed to ALS as well, but researchers could not confirm the diagnosis without spinal cord tissue.

Donna wasn’t surprised but took comfort knowing Jim’s problems weren’t genetic. Going public with his findings is important to Donna to continue Jim’s legacy of giving back to kids.

“He loved kids. He was always encouraging them and talking to them about exercise and doing their homework,” Donna said. “He just wanted people to know there’s a problem.”

Donna says Jim’s message wouldn’t have been to avoid football entirely. He would have supported initiatives for safer play, such as our Flag Football Under 14 campaign, which asks parents to reduce their child’s risk for CTE by not enrolling them in tackle football until they’re at least 14.

For other caregivers, Donna says self-care is vital. Taking time for herself, even just to get laundry done, helped her feel normal during Jim’s decline.

“Get the help, go to support groups, and make sure someone goes with you,” Donna said. “You need to talk to somebody who knows what’s happening and know that you’re not the only one who is going through it.”

Charles Hubbard

Gerald Huth

In the postgame frenzy of the 1960 NFL Championship at Franklin Field in Philadelphia, Gerald “Gerry” Huth found his old coach, Vince Lombardi.

“Hey coach!” Huth joked to the notoriously dour Lombardi. “Thanks for teaching me how to block!”

Minutes earlier, Huth’s block sprung Philadelphia Eagles’ fullback Ted Dean open for the game-winning touchdown against Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers. Five years earlier, Lombardi was Huth’s offensive coordinator for the NFL Champion New York Giants.

The defender wearing 47 in white whom Huth displaced on the play was Jesse Whittenton, a star defensive back for the Packers. 60 years later, Huth and Whittenton are connected in another way. Both of their brains have been diagnosed with CTE by researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank.

Humble beginnings

Gerald Huth was born in July 1933 in the small town of Floyds Knobs, Indiana, six miles outside of Louisville. He was the second oldest of seven children in a devout Catholic family. Huth always aspired to ascend out of his circumstances.

Tragedy struck when Gerald’s father passed when Gerald was just 16 years old. He was quickly thrust into the provider role, a role he would take on for the rest of his life.

Huth turned out for the New Albany High School football team and played well enough to earn a scholarship at Wake Forest University in 1952. In three consecutive seasons, Huth earned a spot on the Carolina College’s All-Star team in 1952, was named 2nd Team All-ACC in 1953, and Honorable Mention All-ACC in 1954.

The New York Giants selected Huth with the 285th overall selection in the 1956 NFL Draft. Football had taken Huth from a county of less than 45,000 people to a city of nearly eight million.

“He tried to help everybody.”

Diane Huth was on vacation from Pittsburgh to South Florida. She missed her flight home and lost her job. Her search for a new job led to a position with an airline. She accepted without quite reading all the fine print. The job required relocation to New York City.

She stayed with a college roommate and while at a friend’s house, Gerald Huth walked in with a case of Ballantine beer. Diane was skeptical of dating a pro football player, but she soon learned Gerald was much different than the playboy pro image she had in her head.

Diane learned Huth’s primary motivation was his family at home in Indiana. He sent money from his Giants’ paychecks home to support his mother. His needs always came second to the needs of those closest to him.

“He tried to help everybody,” Diane said.

His selflessness made him a better offensive lineman. In his rookie season for the Giants he blocked for star quarterback Frank Gifford and halfback Alex Webster and was coached by the legendary Vince Lombardi. The Giants beat the Bears 47-7 in the 1956 NFL Championship. Gifford would later personally thank Huth’s family for Huth’s efforts to keep him safe on the field.

Huth and Diane had started dating that season and quickly fell in love. Gerald hesitated at the idea of marriage because his responsibility to his family in Indiana was too great. Diane said she was willing to accept a share of that responsibility if it meant she could spend her life with him. The two were married in 1958.

Leading headfirst

After Gerald’s championship season with the Giants he was drafted into the U.S. Army and was deployed in Germany for 18 months. There, he coached the Third Division, Fourth Infantry team to a European Championship.

Upon his return in 1959, the Giants traded him to the Philadelphia Eagles. After he won his second championship with the Eagles in 1960, Huth was selected by the Minnesota Vikings in the 1961 NFL Expansion Draft. In Minnesota, the tricks of Huth’s trade were on full display.

In May 2010, the Philadelphia Eagles celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the 1960 Championship team. Huth and several of his old teammates returned to Franklin Field to commemorate the championship.

At 5’11”, Huth had to use every advantage he could to move defenders. On the first block of each game, Huth liked to aggressively use his head to make his defender think twice about messing with him the rest of the game. This style of play led Huth to acquire a whopping eight cracked purple Vikings helmets.

Huth had plenty of concussion stories to accompany the plastic shrapnel. He wrote Diane letters sharing how he was knocked unconscious on a play and returned shortly afterwards. Teammates would later share how he would frequently ask, “What’s the next play?” or “What am I supposed to do?”

Huth retired from football in 1964 at age 30. By then, Gerald and Diane had four children: Sharon, Gerald II, Carol, and Kathleen. The family moved out to Garden Grove, California and Huth began a career with State Farm insurance. The new Huth household resembled the farms of Huth’s youth with animals abound.

“He was, pardon my expression, a real hardass when it came to playing football,” Kathleen said. “But when it came to family and friends, he had a heart of gold. He would give you the shirt off his back.”

Kathleen remembers her father driving the family car after a skiing trip in Mammoth when a horrible snowstorm hit and caused a huge backup of cars. Huth took out a shovel and dug the family car out and then proceeded to dig other cars out as well. The Huth family even had to urge Gerald to stop shoveling others and start driving home.

Huth had strict rules for his children, all born out of the virtues he internalized along the way of his success story. He valued hard work, honesty, and education. Huth went back to school to finish his Wake Forest degree in 1960 and saw what it had done for him. He encouraged Diane to get her accounting degree once they were established in Southern California. His support of Diane’s education led her to become CFO for an international company.

He very much had a lighter side as well and his family says he loved to laugh, even if he was the butt of the joke.

“Not my father”

Throughout life Huth possessed a great intelligence hidden by his characteristic humility. But suddenly, he was slipping.

In his late 40’s, Huth often found himself in the family’s garage unsure why he entered in the first place.

Violent outbursts came next.

“One moment you would be talking to him,” said Kat Willis, Huth’s daughter. “The next moment, he’d be yelling at you for something in your life going on and then you’d start taking it personally and it would get you upset.”

Huth’s problems only grew more intense. Once, he stepped out of the house to visit the mall near the family’s home. Hours later, he called Diane in a panic. He could not find where he parked the car.

When Diane arrived at the mall, she found the car right where Huth would have always parked it. Driving was no longer an option.

Diane felt immense pain as she slowly lost the man who walked in with the Ballantine beer all those years ago. She was heartbroken but took it upon herself to do the best she could for Huth.

“He needed me,” Diane said.

Huth usually called Kat “Kathy.” By his mid-50’s, he started calling her “Carol,” confusing her for her sister.

Huth’s memory problems began to infiltrate his work life. He struggled to remember appointments or keep any of his files straight. He was put on permanent disability from State Farm and retired at age 57. He and Diane moved to Las Vegas when she retired in 1999.

The family enrolled Huth in neurological testing to determine what was causing his decline. Huth’s problems were atypical of an Alzheimer’s case. The best doctors could assume was that he was suffering from advanced dementia. In the mid-2000’s, CTE from Huth’s football career was never discussed.

Football helped lead to fleeting moments where the family had the Huth of old back. Kat’s second husband was a football junkie and was excited to meet his former champ of a father-in-law. At their Big Bear vacation home, her husband watched clips of the 1960 NFL Championship. Huth could still give a thorough play-by-play of the game and rejoiced after big plays just as he had when the plays happened live.

“My second husband didn’t really know the father that my father was,” said Kat. “He was a different person. And it makes me sad because my husband’s very much like my dad. It was sad that he couldn’t have that connection.”

Glimpses of the old Gerald also came through when he was with his pets. He had dogs all his life, including three different miniature dachshund named Heidi. Diane gave Heidi III to Huth for his 50th wedding anniversary, a gift he would repeatedly say was the best he ever received.

On November 20, 2010, Huth was inducted into the Wake Forest University Sports Hall of Fame during a halftime ceremony of a game against Clemson. Upon returning home from the ceremony, Huth fell off a curb at his Las Vegas home and fractured his tibia. He was taken to the emergency room and later sent to the hospital for rehabilitation.

While Huth was in the hospital Diane received a phone call. Four attendants were required to hold Huth down in the facility. He was too violent to come home and was moved to a memory care facility.

Huth’s months in memory care were demoralizing for him and his family. When his children visited, Huth told them his presence in the facility meant he was “at the end of the line”. Diane continued visiting him daily, and each time she had to leave alone. Huth could not grasp how his violence precluded him from living with Diane.

On her last visit, an incensed Huth said, “You’re always leaving me. Why don’t you get a [expletive] divorce?”

On February 11, 2011, Huth died of a blood clot in his lung. He was 77 years old.

“It was difficult to see him go the way he did. I just loved the guy,” Diane said. “I still do. I tell him that every day. He was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Relief

After death, Huth’s brain was sent for study to the UNITE Brain Bank. Huth agreed to donate his brain before his death in hopes research could explain why he had such problems in the last decades of his life. Huth’s posthumous brain donation was his last act in a lifetime of generosity.

“He was such a generous man,” Kat said. “And I know that if he knew the effect that his legacy could have and the changes that they could make with football based on him and all of the other Legacy Donors, I know that he would want to be a part of that very special group.”

Kat and her family were touched by the care and delicacy the Brain Bank team took with Huth’s brain. Researchers at the Brain Bank diagnosed Huth with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The diagnosis brought relief and the gift of knowledge to the family. There was a reason for Huth’s changes.

“My dad was such a kind and loving person,” Kat said. “But he could be so mean. And that wasn’t my dad, but I didn’t know what was wrong with him. Knowing that he had CTE was a relief because I knew it wasn’t his fault.”

Diane profoundly misses her husband of 53 years and the countless memories the two made together. She still has Heidi III as a living symbol of her and Gerald’s union together.

For other partners in her shoes, Diane preaches patience.

“I would tell them to be very, very patient,” Diane said. “Try to understand that what you’re dealing with truly isn’t them. It is their brain and their brain is not functioning properly.”

Kat has given to CLF every month since 2012 and has all her gifts matched by her employer. She is proud to have her father in the group of hundreds of Legacy Donors who have contributed to CTE research and awareness.

“CTE is a real thing,” Kat said. “And all of these legacy donors that have donated their brains have paved the way to help the future and to help people understand how devastating this disease can be.”