Jack Jacobson

Darrius Johnson

John “Curley” Johnson

John Henry Johnson

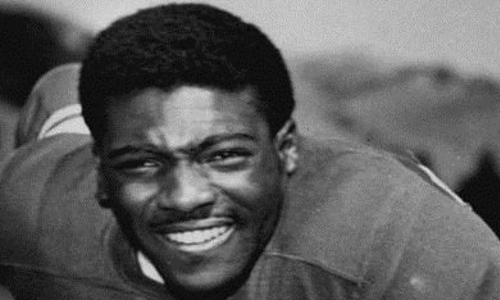

John Henry Johnson’s remarkable journey started in 1929, in the rural town of Waterproof, La. In the segregated South, Johnson did not have the option to attend high school near his hometown, so he moved to the Bay Area to live with an older brother at the age of 16. At Pittsburg High School, Johnson played organized sports for the first time, putting together a dominant prep career as a football, basketball, and track and field athlete.

Upon graduation in 1949, Johnson chose to play football at nearby St. Mary’s College, where he made history a year later as the first Black player in program history. He was the first Black student-athlete to compete against a University of Georgia team and was carried off the field by the home fans following a standout performance in a stunning 7-7 tie against the visiting Bulldogs.

St. Mary’s discontinued its football program after the 1950 season, prompting Johnson to follow several teammates transferring to Arizona State, where he continued to play on both sides of the ball in addition to returning kicks. The San Francisco 49ers selected Johnson in the second round of the 1953 NFL Draft, and after one season in the Canadian Football League, the fullback embarked on a legendary NFL career.

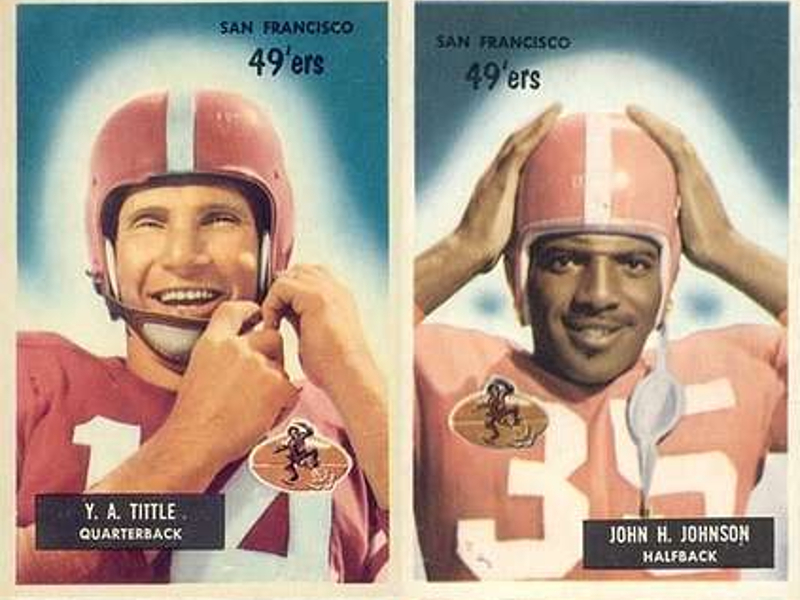

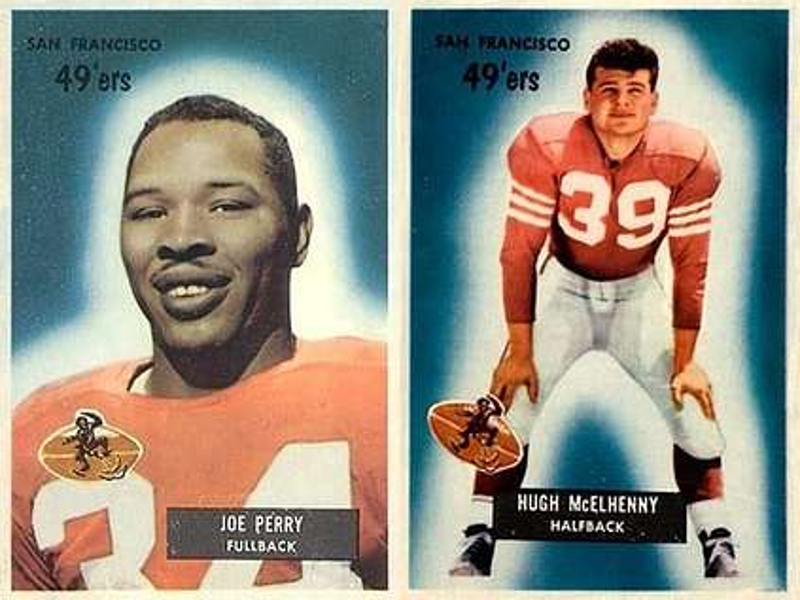

In San Francisco, Johnson joined quarterback Y.A. Tittle and running backs Joe Perry and Hugh McElhenny to form the “Million Dollar Backfield.” The four backfield mates captivated Niners fans for three seasons and are the only “T formation” fully enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

John Henry Johnson was one of four Hall of Famers making up San Francisco’s “Million Dollar Backfield.”

As his on-field success raised his nationwide profile, Johnson enjoyed raising his family when he had time away from football. John Henry’s daughter Kathy Moppin said her father loved to dance and always had a joke for his six children. She said he was proud of his place in the Bay Area community and enjoyed visiting schools with his 49ers teammates.

Kathy said because of her father’s playful demeanor off the field, she did not realize until late in his career he developed a reputation as one of the toughest players in the NFL, frequently sacrificing his body on crushing blocks and bruising runs between the tackles.

“He got hurt quite a bit,” Kathy said. “I can remember he had teeth knocked out and shoulders dislocated, and back then, they used smelling salts when they got lightheaded on the field. He went through a lot of trauma to his body.”

The 49ers traded Johnson to Detroit before the 1957 season, and that year he helped lead the Lions to their most recent NFL championship. Johnson joined the Pittsburgh Steelers ahead of the 1960 season. Though he was 31, Johnson still had his best individual seasons ahead of him. He earned the final three of his four Pro Bowl honors in his mid-30s. In 1964, at 35, Johnson became at the time the oldest NFL player to rush for 1,000 yards in a season.

When Johnson retired at 37 following the 1966 season, he ranked fourth on the all-time rushing list. He finished his career with the Houston Oilers but returned to Pittsburgh to start a new career with Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania and later with Warner Communications. Year after year, the Pro Football Hall of Fame overlooked Johnson, who was considered by peers to be one of the best all-around running backs in NFL history.

Finally, in 1987, Johnson got the call to Canton, joining his “Million Dollar Backfield” teammates in the Hall of Fame. He joked at the time that the nickname was far from literal, as he never earned more than $40,000 in an NFL season.

Back in the Bay Area, Kathy said she would speak with her father on the phone two to three times per week. However, when John Henry reached his 50s, Kathy and others close to John Henry noticed changes in his willingness and ability to communicate, on the phone and face to face. A friend in Pittsburgh called Kathy and encouraged her to check on her dad, which she did with the help of John Henry’s wife Leona.

“He still had a good sense of humor, but he was just a lot slower,” Kathy said. “It took him a while to answer if you asked him something. I noticed early on he was having some symptoms of something. I didn’t know what it was.”

In 1989, with Johnson’s cognitive issues affecting his daily life, Leona enrolled Johnson in an Alzheimer’s disease study in Cleveland. This led to a formal diagnosis, and Johnson retired from his post-playing career. Kathy said it was a difficult time for their family, with most of them more than 2,000 miles away from their dad.

“I was very sad, and my siblings were sad, too,” Kathy said. “My dad, at that point, didn’t really get a sense for how serious things were.”

Kathy said despite his struggles at home, John Henry looked forward to annual trips to Canton, Ohio for Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. Clad in their gold jackets, Johnson and his fellow Hall of Famers cherished the opportunity to reminisce about the glory days of decades past.

As the years went on, Kathy said, the late-summer tradition became an eye-opening experience for her family and other relatives of NFL alumni. In Canton, she recalled more wives, sons, and daughters privately sharing concerns about their loved ones’ health years after their football careers ended.

“Every year when I went back, there was more and more guys having symptoms like my dad,” Kathy said. “That’s what got me. Every few years, I could see the next husband with symptoms and the wife having to push him in a wheelchair.”

John Henry returned to California after his wife passed away in 2002. Kathy became his primary caretaker, which presented challenges she could only face with help from her husband and siblings.

“When you sign up for that, you don’t know how hard it’s going to be and how it changes your life,” Kathy said.

Then in his 70s, John Henry struggled further with memory and communication. Though it had been 50 years since he played for the 49ers, he still received fan mail from fans in the Bay Area. When he signed autographs, Kathy said she had to remind him which year to write under his signature when he mistakenly wrote the incorrect year of his “HOF” induction.

Johnson’s struggles with Alzheimer’s included a few instances of wandering from home, which only added stress to Kathy as a caretaker. She said she installed a bell on her front door after police returned her father, finding him waiting at a nearby bus stop. He told her he was on his way to join his Niners teammates for practice that afternoon.

“It was hard for me,” Kathy said. “It was sad to see him decline like that. I cried many a night. But all my siblings helped out, and I was able to get through it. It was sad to see.”

John Henry Johnson died in 2011 at the age of 81. At the time, the NFL’s concussion crisis and the growing understanding of CTE led Kathy to consider donating her father’s brain for study. His San Francisco teammate Joe Perry had died five weeks earlier, and with encouragement from Joe’s widow Donna, Kathy elected to donate her father’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank.

Boston University researchers diagnosed Johnson with stage 4 CTE, the most advanced stage of the neurodegenerative disease.

“It kind of gave me some closure,” Kathy said. “I was very shocked and sad to hear that, but then I understood more why my dad acted like he did.”

Kathy shares her father’s Legacy Story to celebrate his life while raising awareness about the potential long-term consequences associated with tackle football’s repetitive head impacts. While helmet technology has improved, Kathy said today’s players face most of the same risks as her father, and she hopes more parents and coaches educate themselves about CTE to help prevent similar outcomes to what her family experienced.

She hopes her father’s story leads coaches and administrators to consider policies and rule changes with long-term brain health in mind. Kathy and her family remember John Henry Johnson as a “loving, kind, funny guy,” a man who put smiles on the faces of fans from coast to coast.

“I was shocked to see so many people still remembered my father, and they remembered him as a hard player, a tough player,” Kathy said. “He loved football, and he was loved by his family.”

Ron Johnson

Calvin Jones Jr.

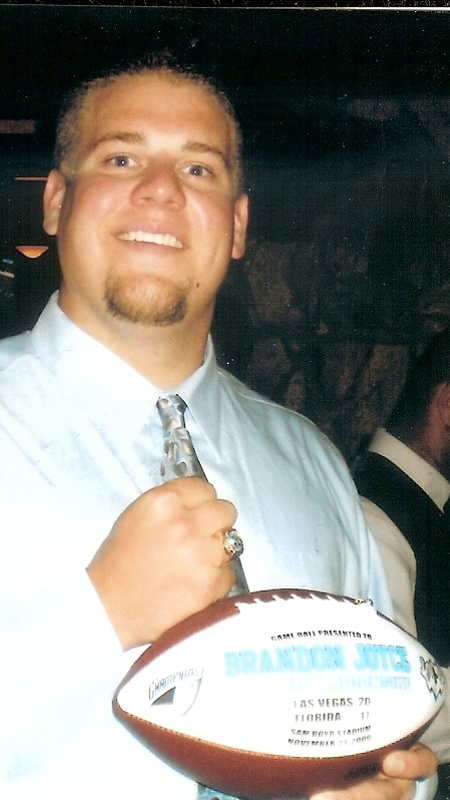

Brandon Joyce

Father and son are not only united in death, but are also together forever as Legacy Donors.

Terry’s and Brandon’s passion for football was endless; so much so that both men decided to become donors to help promote medical and scientific research for brain related injuries. Their decision to be part of the same team for concussion advocacy, awareness, education, understanding, diagnosis, and injury management will hopefully help protect players of all ages and make the game they loved that much safer.

Brandon was the first Concussion Legacy Foundation donated brain of a professional and former NFL football player to be diagnosed “without” evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) by the research team at the Boston University CTE Center. I distinctly remember watching Bob Costas’s Super Bowl XLVI special in 2012 and listening to the discussion about the issues relating to safety on the football field. Bob Costas had several guest, including Concussion Legacy Foundation Co- Founder and Executive Director Christopher Nowinski, who reported that of the 19 former NFL brains that had been donated, 18 were diagnosed with CTE. Only a year later at Super Bowl 2013, it was widely discussed by several media organizations and NFL players about football’s concussion crisis where 34 out of the now 35 donated NFL brains were diagnosed with CTE. That one NFL donated brain “without” CTE was my son’s, Brandon Patrick Joyce, age 26. One of the other 35 NFL donated brains studied “with” CTE, was Brandon’s father, Terrance Patrick Joyce, age 56. Terry was diagnosed by neuropathologist Dr. Ann C. McKee with CTE.

Brandon was the victim of an unspeakable crime: murder. On December 24, 2010, four cousins, all with extensive criminal histories, shot Brandon in the head during a confessed, planned robbery. Four days later, Brandon succumbed to his injuries and passed away on December 28, 2010, at the age of 26. We were then forced to endure not only the indescribable grief of losing Brandon but also a crash course on criminal proceeding. My daughter, Dr. Lindsay Joyce, and I have had to go through an unimaginable, excruciatingly painful legal process of the prosecution of all four of my son’s murderers, all of which have since plead guilty and are currently serving 20 to 45 years in prison.

In life, Terry, my husband and former NFL football player, and Brandon were alike in many ways; so much so that Brandon described the closeness of their relationship as if they were literally one and the same. Upon learning that his father’s brain cancer had returned and after witnessing his dad’s debilitating depression, Brandon texted me, “Mom you are the best mother ever but I love my dad and I feel like him and I am him. Get him that anti-depressant; help him now because he is stronger than that.”

Both Terry and Brandon experienced the dream of becoming NFL football players. Terry was a former St. Louis Cardinal, Los Angeles Ram, San Francisco 49er and Detroit Lion. He played both Punter and Tight End. Brandon was an Offensive Tackle for the United Football League (UFL) Toronto Argonauts and had been on his hometown team the St. Louis Rams roster the year he was killed. Both were Rams, Terry in 1978 and Brandon in 2010. They were big, smart, massive, strong, vibrant, and funny men, both 6’6″ tall weighing over 300 pounds each. Both shared a passion for sports, including: football, basketball, baseball, golf, and were blessed with amazing athletic abilities.

Brandon was quoted April 30, 2010, while at Ram’s Rookie Camp in an interview with Jim Thomas, sportswriter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, as saying, “I’m 25 years old and I’m out here having the time of my life. I get paid to play a game. And when I go to work, they don’t call it working, they call it playing. I wish I had bigger lips so I could smile bigger. I love this!”

Terry was recuperating at home after brain surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy when Conrad “Big Red” Dobler (a close friend, former NFL teammate, and Pro Bowler) and Jim Hanifan (NFL Head and Offensive Line Coach) came for a visit. Terry, Brandon, and I were all there when Conrad mentioned the study of former NFL players who had donated their brains for the research of CTE. Conrad mentioned that he planned to donate his brain to the study and suggested Terry should do the same.

After Brandon died, it was an understandably very confusing, devastating, and emotionally- debilitating time for our family. It wasn’t until February of 2011 when we learned from the Medical Examiner that they had Brandon’s “brain specimen” to release. We were stunned to learn that they had retrieved and saved Brandon’s entire brain. I asked Lindsay to call and ask Conrad Dobler about which organization he was speaking about that day when he was discussing the study of NFL brains. Conrad then contacted Christopher Nowinski on our behalf. Soon thereafter, Christopher Nowinski spoke with my daughter and discussed the details of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center Brain Donation Registry. It was that week when we decided to not only donate Brandon’s brain to the BU CTE Center, but also Terry decided to donate his brain as well.

An excerpt quoted from Dr. Lindsay Joyce’s Victim Impact Statement at the sentencing of one of Brandon’s murderers:

“Brandon was an amazing son, brother, boyfriend, cousin, nephew and friend. He was a big man with an even bigger heart. He loved his family! When our dad was diagnosed with brain cancer, he was devastated but remained motivated to help him during the long road ahead. From waiting for him outside the ICU as he came out of the first of two brain surgeries, to encouraging him to get out of bed when he didn’t have the energy, to checking on him during chemo and radiation treatments, to bringing him broccoli cheddar soup because ‘it has anti-oxidants in it.’ Brandon was always motivating my dad ‘to keep fighting and never give up.’ Brandon, however, never accepted our dad’s mortality.

Brandon wasn’t just funny; he was comical. He was quick-witted and sharp, always able to come up with a one-liner on a whim. I never laughed as much, or as hard as I did when I was with him. I miss laughing with my brother.

Brandon was a very motivated, well-liked, successful, and undeniably gifted athlete. My brother was a charitable, generous, and caring person, always willing to help others. Nothing speaks to that more than his donation to the BU CTE Center for the study of CTE. Brandon had signed the back of his license to be an organ donor. Unfortunately, the medications he received in attempts to save his brain, in turn, sacrificed his organs. He was no longer a candidate for organ donation. It wasn’t until we received a call from Boston University that we knew some good could still come out of this horrific event. Brandon’s brain was sent to Boston University to be studied and analyzed as part of an ongoing research project. The goal of the research is to “identify the neuropathology, pathogenesis, and disease course of progressive dementia seen in some athletes as a result of not only concussions but also repetitive forces on the head.” Brandon’s donation will live on forever.” – Dr. Lindsay Joyce

An excerpt from my victim impact statement about Terry’s recorded video:

“On March 21, 2011, Brandon’s girlfriend Rachel and my daughter Lindsay traveled to Las Vegas, Nevada to accept Brandon’s second UFL Championship ring from Coach Jim Fassel of the Las Vegas Locomotives. As I listened over the phone to hear Lindsay accept Brandon’s second UFL Championship ring on his behalf, I laid on my bathroom floor, holding my dog, sobbing hysterically in attempts to keep my paralyzed, grief-stricken, bedridden husband from hearing me cry. I lay there remembering how proud Brandon was after his first UFL Championship and the text he had sent to his dad:

“Today was the greatest day of my life. Because I know I made you proud. You knew I could always do it and that’s the “you” in me, always keep fighting and never give up. Because all I want out of life is to be as good as you. I love you dad. You’re the best.” – Brandon Patrick Joyce

In March of 2011, two days after all four murderers were indicted, we recorded Terry speaking about our wonderful son. We did this knowing Terry would most likely not live to give his Victim Impact Statement in person. I am so thankful he was still able to make his voice heard at the sentencing hearings. In his videotaped statement, you see a broken, frail, weak man with little resemblance to the strong, confident, former football pro, and leader Terry had always been. In his recorded statement Terry says, “I just can’t believe someone would try to do this to our family. We have never done anything to hurt anybody or inflicted pain on anybody.”

When asked how he wanted our son to be remembered; what was Brandon’s legacy? It wasn’t about Brandon’s perseverance, motivation, determination or even his great athleticism. Instead, Terry said he wanted Brandon’s legacy to be that “he was a good guy, a really good guy.”

Brandon was born on September 5th, 1984. Brandon had a real drive, passion, and love for all sports. He began playing T-ball and soccer at age four; tennis, basketball, baseball, and golf would follow later. Terry had worked for Rawlings Sporting Goods in 1980 and had always believed in providing the best equipment for our children. Brandon was big for his age and would beg us to let him to play football. Terry believed speed and agility were the most important factors to a developing, fast-growing, young athlete and encouraged Brandon to stay with soccer, baseball, and basketball. Brandon would not start junior football until the summer of 1996, just before his 12th birthday.

Brandon loved playing football and excelled as quarterback, defensive end, kicker, and special teams, only leaving the field when his team punted. And when his true size and strengths became apparent, he would later play offensive guard, offensive tackle, and defensive tackle for his high school football team.

During Brandon’s senior year at Duchesne High School, Class of 2003, he was selected to the Missouri All-State First Team as an Offensive Lineman. The Missouri State High School Activities Association of Coaches and the Sportswriters recognized Brandon as well. The St. Louis Post Dispatch selected Brandon to their “All-Metro First Team Offense” stating that he was one of the most “dominating players” in the Gateway Athletic Conference. Brandon was captain of Duchesne’s football team and also started for their basketball team as center.

In college, Brandon played Offensive Tackle and sometimes Offensive Guard when needed. He went at everything head first, helmet-to–helmet, especially in the red zone and on all short yardage 3rd and 4th downs. He was always a “head banger” fighting for those inches and yards. You could see and hear from the stands the crushing blows of their helmets and pads colliding. After the game, Brandon would describe some big plays, “as seeing stars” or “being messed up after that one!”

Brandon was recognized as an Indiana University Alpha Beta Honoree and named to the Illinois State University’s “All-Newcomer Team.” After graduating with his Bachelor’s Degree in Business from Illinois State, Brandon signed with the Toronto Argonauts Canadian Football League on his birthday, September 5th, in 2008.

In 2009, he was drafted to the Las Vegas Locomotive (UFL) team, eventually winning the UFL Championship in their inaugural season.

In April of 2010, Brandon was invited to the Rams Rookie minicamp and signed as a St. Louis Ram in May. Brandon would not make the final roster and returned to the Las Vegas Locomotives in August. Shortly thereafter, Brandon suffered a severe knee injury that required surgery.

Brandon spent the last four months of 2010 in Birmingham, Alabama rehabilitating his knee with some of the top Sports Medicine doctors in the nation. His first week there, Brandon met a young Medical Assistant, preacher’s daughter, and the love of his life, Rachel Hubbard. Birmingham was a very familiar place for our family as Lindsay had played Division 1 volleyball for the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and had graduated with a Bachelors of Science degree in Biology in 2004. We visited Brandon twice in Birmingham during his recuperation and fell in love with Rachel as well. Not long after, Brandon posted on his Facebook page the comment, “She’s the one!”

Brandon was home for just 24 hours before he was shot. It was during this time that he spoke to me about how he planned on asking Rachel to marry him on New Year’s Eve.

On June 17th, 2011, my loving husband, Terry Joyce, died at the age of 56 at home, surrounded by me and my daughter. A parent should never have to bear witness to their child’s murder; a parent should never have to bury their child; a parent should not have to die without both of their children by their side. Exactly six months to the day of Brandon’s shooting, we buried Terry next to Brandon. Jackie Smith, Hall of Fame Tight End, provided an amazing voice and tribute to both Terry and Brandon by singing “O’ Danny Boy” at both of their memorials.

I have been enthusiastically cheering my whole life. I have a true love and passion for football, as well as many other sports. My husband Terry was inducted to Highland Community College Athletic Hall of Fame as a three-sport athlete and became an All-American football player for the Missouri Southern State University Lions as a punter and tight end. Terry went on to live the dream of playing in the NFL. Our daughter Lindsay played Division 1 college volleyball for UAB. Our son Brandon played college football for Division 1 Indiana and 1A Illinois State and professional football for the CFL, UFL and NFL.

In high school and college, Brandon would get “dinged up,” but would never want to miss a minute, snap, play, or down. His sacrifice was all for the love and excitement of the game. Brandon’s college football teammates, too, would laughingly describe their head injuries as feeling dazed or goofy, getting their bell rung, or having just a bad headache. It are those dangerous cumulative repetitive hits to the head, left mostly undiagnosed, that the Concussion Legacy Foundation and Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy are bringing critical awareness to and contributing the necessary research in hopes of ensuring the safety of all athletes.

It is our hope that by sharing Brandon’s and Terry’s stories we will bring attention to the inherent dangers of concussions, that the very important research available through the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the BU CTE Center will be shared and create additional awareness about repetitive concussive and sub-concussive brain injuries, and that these discussions will offer an informed dialogue with parents, youths, coaches, athletes of all ages, and the news media to have a better understanding of the scope of the concussion problem. As Legacy Donors, Terrance Patrick Joyce and Brandon Patrick Joyce, father and son, will live on together, both big men, forever on the same team.

Terry Joyce

Father and son are not only united in death but are also together forever as Legacy Donors. Terry’s and Brandon’s passion for football was endless; so much so that both men decided to become donors to help promote medical and scientific research for brain related injuries. Their decision to be part of the same team for concussion advocacy, awareness, education, understanding, diagnosis, and injury management will hopefully help protect players of all ages and make the game they loved that much safer.

My son Brandon was the first Concussion Legacy Foundation donated brain of a professional and former NFL football player to be diagnosed “without” evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) by the research team at the Boston University CTE Center. I distinctly remember watching Bob Costas’s Super Bowl XLVI special in 2012 and listening to the discussion about the issues relating to safety on the football field. Bob Costas had several guests, including Concussion Legacy Foundation Co-Founder and Executive Director Christopher Nowinski, who reported that of the 19 former NFL brains that had been donated, 18 were diagnosed with CTE. Only a year later at Super Bowl 2013, it was widely discussed by several media organizations and NFL players about football’s concussion crisis where 34 out of the now 35 donated NFL brains were diagnosed with CTE. That one NFL donated brain “without” CTE was my son’s, Brandon Patrick Joyce, age 26. One of the other 35 NFL donated brains studied “with” CTE, was Brandon’s father and my husband, Terrance Patrick Joyce, age 56. Terry was diagnosed by neuropathologist Dr. Ann C. McKee with CTE.

Brandon was the victim of an unspeakable crime: murder. On December 24, 2010 four cousins, all with extensive criminal histories, shot Brandon in the head during a confessed, planned robbery. Four days later, Brandon succumbed to his injuries and passed away on December 28, 2010 at the age of 26. We were then forced to endure not only the indescribable grief of losing Brandon but also a crash course on criminal proceedings. My daughter, Dr. Lindsay Joyce, and I had to go through an unimaginable, excruciatingly painful legal process of the prosecution of all four of my son’s murderers, all of which have since plead guilty and are currently serving 20 to 45 years in prison.

In life, Terry and Brandon were alike in many ways; so much so that Brandon described the closeness of their relationship as if they were literally one and the same. Upon learning that his father’s brain cancer had returned and after witnessing his dad’s debilitating depression, Brandon texted me, “Mom you are the best mother ever but I love my dad and I feel like him and I am him. Get him that anti-depressant; help him now because he is stronger than that.” Both Terry and Brandon experienced the dream of becoming NFL football players. Terry was a former St. Louis Cardinal, Los Angeles Ram, San Francisco 49er, and Detroit Lion. He played both Punter and Tight End. Brandon was an Offensive Tackle for the United Football League (UFL) Toronto Argonauts and had been on his hometown team the St. Louis Ram’s roster the year he was killed. Both were Rams, Terry in 1978 and Brandon in 2010. They were big, smart, massive, strong, vibrant, and funny men, both 6’6″ tall weighing over 300 pounds each. Both shared a passion for sports, including: football, basketball, baseball, golf, and were blessed with amazing athletic abilities.

Both Terry and Brandon were marked with the same scar from brain surgery prior to their passing; Terry’s, a result of brain cancer and Brandon’s a result of a gunshot wound to the head at the hands of others (homicide). Both brains, NFL father and son, were donated to the BU CTE Center. On June 17, 2011, my loving husband, Terry Joyce, died at the age of 56 at home, surrounded by me and my daughter. A parent should never have to bear witness to their child’s murder; a parent should never have to bury their child; a parent should not have to die without both of their children by their side. Exactly six months to the day of Brandon’s shooting, we buried Terry next to Brandon. Jackie Smith, Hall of Fame Tight End, provided an amazing voice and tribute to both Terry and Brandon by singing “O’ Danny Boy” at both of their memorials.

Although Terry died in June of 2011, well before the completion of criminal proceedings, he was able to make his voice heard in the sentencing hearings of all four of Brandon’s convicted murderers. In Terry’s videotaped Victim Impact Statement, you see a broken, frail, weak man with little resemblance to the strong, confident, former football pro, and leader he had always been. Terry says, “I just can’t believe someone would try to do this to our family. We have never done anything to hurt anybody or inflicted pain on anybody.” Terry spoke about how Brandon had always helped young athletes at football camps. Upon hearing about one young man who couldn’t afford new shoes, instead using duct tape to hold together an old pair, Brandon gave the young man several pairs of his own football shoes. (We would later donate all of Brandon’s athletic shoes and football equipment to the youth’s high school). When asked how he wanted our son to be remembered; what was Brandon’s legacy? It wasn’t about Brandon’s perseverance, motivation, determination or even his great athleticism; instead, Terry said he wanted Brandon’s legacy to be that, “He was a good guy, a really good guy.”

At the age of 12, Terry won Missouri’s “Punt, Pass & Kick” competition and was awarded a plaque and Cardinal helmet. Terry participated in football, basketball, baseball, golf, and track & field while attending Knox County High School from 1968 to 1972. Terry’s #10 Jersey was retired at a half-time ceremony of the Knox County varsity football home opener on September 9th, 2011. A marquis is planned near the entrance of the Knox County R-1 campus east of Edina in memory of Terry, the only NFL player to date in school history.

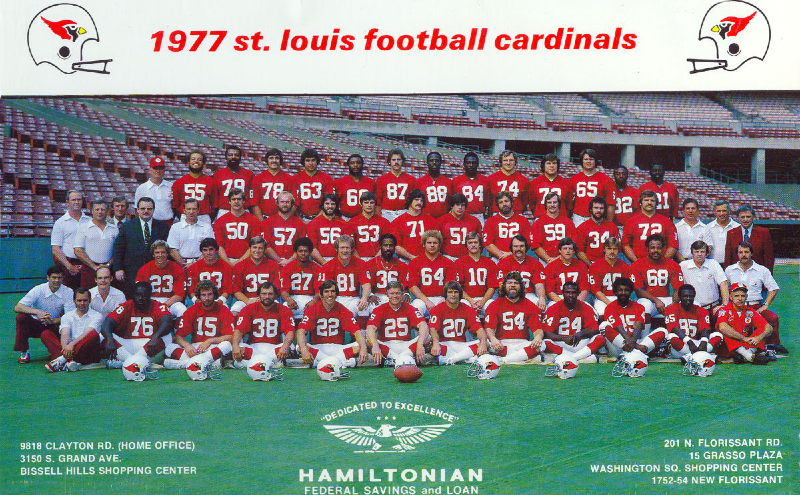

Terry was so gifted athletically that he was not only offered contracts to play professional football but also professional baseball. As a senior at Knox County High School, Terry was scouted and offered a baseball contract by the Cincinnati Reds. He, however, chose college football and went on to play at Highland Community College in Kansas. Terry was inducted to Highland Community College Athletic Hall of Fame as a three-sport letterman. As a member of the Scottie Football Team, he played quarterback, tight end, and punter. On the basketball court, Terry played forward and center, and on the baseball field, he was the team’s pitcher, along with seeing action at first and third base. After he left Highland Community College, Terry attended Missouri Southern State University, where he was recognized as an All-American Tight End and Punter. During his senior year, Terry led the nation in punting average and was eventually signed by the St. Louis Football Cardinals.

Terry and I met in Kirksville, Missouri, in May of 1976. I was 21-years-old entering my senior year at Northeast Missouri State-Truman. Terry was 21-years-old, too, and lived in the nearby small town of Edina, Missouri, total population of 1400. He was at home working-out nonstop getting ready for football camp starting in July in St. Louis. I had plans to go back to St. Louis, where I was born and raised, to begin student teaching in Elementary and Special Education. It was the perfect match! Together, we had so many things in common, including a passion for sports. I had been a loyal St. Louis Cardinal fan my whole life; my dad was a season ticket holder and former high school football coach and assistant basketball coach. I have been enthusiastically cheering for sports teams my whole life, having a true love for football along with a great passion for many other sports.

Terry and I were inseparable from the moment we met. Together, we headed to St. Louis in July. We were married May 27, 1978. Terry would go on to live the dream of playing in the NFL. Terry was coached by future Hall of Famer Don Coryell and played with NFL Hall of Famers, Tight End Jackie Smith, Offensive Lineman Dan Dierdorf, and Defensive Back Roger Wehrli on the St. Louis Football Cardinal’s team in 1976 & 77.

Terry and I had two children, Lindsay Ann Joyce born April 4, 1982 and Brandon Patrick Joyce born September 5, 1984. Our children, taking after their athletically-gifted father, both became Division-I scholarship collegiate athletes, our daughter Lindsay played Division 1 volleyball for the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and our son Brandon played Division 1 college football for Indiana and 1A Illinois State. After graduating from UAB with her Bachelors of Science in Biology, Lindsay went to medical school at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Upon earning her Doctorate in Medicine, M.D., Lindsay went on to complete her residency training in Emergency Medicine at the University of Louisville Hospital, Level I Trauma Center, and is currently an Attending Physician in Emergency Medicine. After College, Brandon enjoyed a career in professional football with the CFL, UFL and NFL.

Terry had many, many best friends, and people who truly loved him. From his friends he was also given a lot of nicknames; “The Big Man”, “The Man” “#87″, “Big Foot”, “Daddy T”, “TJ”, “Friendly Terry” and “Big Buddy” to quote a few.

Ron Meyers had these words to say about Terry’s friendship and mentoring his son, Will Meyer #39 IU, first team freshman All-American & Big Ten Defensive Freshman of the Year honors, roommate and friend to Brandon:

“For Will, Terry was kind of a second father and role model/mentor during an important time of his life. Terry’s constant encouragement for the “headhunter” was something that kept feeding his desire to perform at the highest level he was capable of. For me, Terry was simply my best friend. The best thing I can say about him is that he acted like everyone’s best friend – from the parking attendant at IU, to the ticket lady, to the restaurant manager (JB), to the trainer. He had that kind of charisma and interest in the people around him. He was not too good for anyone. And he saw the best in everyone he met. I will never forget ‘The Man’ or your entire family.”

Edina native, Knox County Sports writer, David Sharp wrote in the Edina Sentinel on June 29, 2011 (excerpt):

“Terry was hired by the Rawlings Sporting Goods Company of St. Louis. He later joined a St. Louis area Miller brewing company distributor as a salesman. Later became The General Manager for Best Beers. Terry Joyce moved on to one of the largest adult beverage distributors in the Midwest. Joyce had an 18-year career with Major Brands, one of the top Missouri businesses in terms of sales and coverage area. After rising to the top of the football world, Terry Joyce ascended to the upper levels of the St. Louis area business community. He eventually became the General Sales Manager and Vice President of Sales for Major Brands Premium Beverage Distributors in St. Louis.”

NFL Alumni spokesperson Jim Morris offered this comment to the Edina Sentinel from his New Jersey office:

“The NFL Alumni wants to tell the Joyce family that the thoughts and prayers of the entire NFL Alumni organization are with them as they go through this time. Terry Joyce had a tremendous impact on the football community…. He (Terry) sat on the St. Louis NFL Alumni Board of Directors. He touched many lives with his work with the NFL Alumni, and also during his bought with cancer.”

The Edina Sentinel continued to say: Terry Joyce played in numerous charitable golf tournaments for Missouri Southern State, the NFL Alumni and many others. Joyce was a championship flight golfer until the final years of his life. Conrad Dobler, also known as ‘Big Red’, was one of the most feared guards in the NFL during his ten year playing career. Dobler was a Pro Bowler in 1975, 76 and 77. Conrad Dobler currently works for the NFL Alumni in their Kansas City office. According to NFL Alumni spokesman Jim Morris, the St. Louis NFL Alumni chapter has disbanded.

Conrad Dobler offered the following comments to the Edina Sentinel of his St. Louis Cardinal teammate:

“I had the opportunity to play with Terry Joyce for two years. He was one of the biggest punters ever in the NFL. He could really boot the ball. He was a really good guy. If you needed anything, Terry was there to help you… Terry certainly gave back to the community he lived in. That’s what made him special. He was bigger than life!”

Conrad continued…

“Terry could have probably had a nice career as a tight end and a punter. We had a pretty good tight end in Hall of Famer Jackie Smith and JV Cain. More yards are exchanged in the punting game than any other facet of the football game. Terry covered more yards than anyone else. He had more yards than (running backs) Terry Metcalf and Jim Otis put together. Most kickers and punters are kind of strange guys. That wasn’t Terry. He was right in the middle of it all in practice. He ran the opposing defenses for us in practice. Outside of football, he always made sure I had engagements to do when he worked for the Miller Distributor.”

Conrad Dobler had national endorsements for Miller Beer. Dobler was one of the ‘Miller All-Stars’ of his era. He said of Terry, “He took care of his own. He helped raise a lot of money for charity. Terry got involved. If you knew Terry, you couldn’t-not like the guy.”

Clarence Cannon, an All-Conference basketball player at Knox County, offered the following comment on playing with Terry Joyce at Knox County:

“Terry was the finest teammate anyone could ask for in sports. He had a great sense of humor and quick wit. When he walked onto the baseball diamond, the football field or the basketball court he became the most intense and focused person I ever knew. I don’t think there is any question he was the best all-around athlete Knox County High School ever saw.”

Another former teammate at Knox County and current Marceline High School teacher, Brian McGlothlin, remembered Terry by saying:

“What many people do not realize is the level of fierce competitiveness he possessed. As his teammate, I was often caught up in the middle of the game just watching him perform. He was one of my sports heroes growing up.”

Milan head football coach and Knox County R-I graduate John Dabney said:

“I remember sitting in a third grade classroom at St. Joe and feeling the thrill when I heard Terry Joyce had made the St. Louis Cardinals football team. I looked through a lot of Topps Football Cards before I got Terry’s card. I still have the card today. I don’t think Terry really got the recognition he deserved in Knox County. He was a great athlete, no doubt the best athlete ever at Knox County.”

Terry had at least two known concussions. One occurred while playing quarterback for the Highland Scotties. Terry was ‘knocked out’ on a pass play and ended up face down in a muddy puddle. The coaches and players ran onto the field to roll Terry’s mud-caked body over so he could breathe. Dale Miller, a lifelong friend and teammate, remembers helping Terry off the field. Terry would later jokingly describe the story of how he woke up in a fog on the bench not knowing what had happened, where he was, or how much time had passed. This was the typical story of concussions back in the day; players were told to ‘shake it off’ and get right back into the game.

It is our hope that by sharing Terry’s and Brandon’s stories we will bring attention to the inherent dangers of concussions, that the very important research available through the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the BU CTE Center will be shared and create additional awareness about repetitive concussive and sub-concussive brain injuries, and that these discussions will offer an informed dialogue with parents, youths, coaches, athletes of all ages, and the news media to have a better understanding of the scope of the concussion problem. As Legacy Donors, Terrance Patrick Joyce and Brandon Patrick Joyce, father and son, will live on together, both big men, forever on the same team.