Former Rockies president Keli McGregor’s legacy lives on

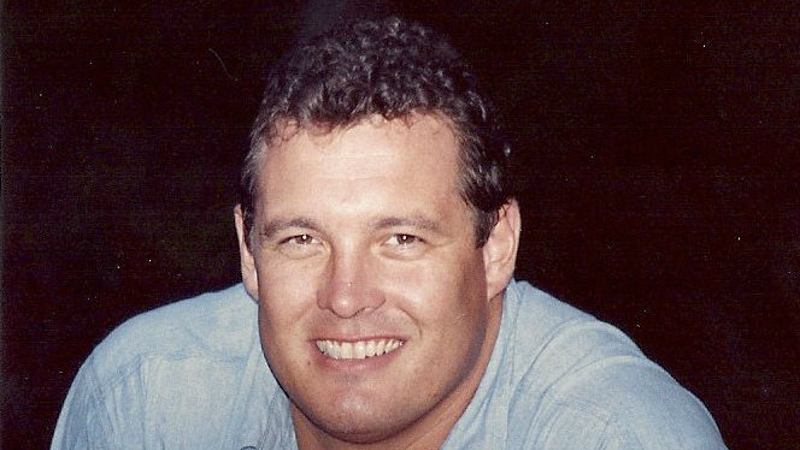

DENVER (AP) — It’s been a year since Rockies President Keli McGregor, a 6-foot-7 fitness fanatic and former NFL player who was the picture of health, died on a business trip in Utah at age 48, sending shock waves through the club and the Colorado sports and business community.

His legacy lives on in many ways big and small, both in Colorado and in Arizona, where the planning and construction of the Rockies’ new spring training complex in Scottsdale consumed much of his final years.

Wednesday marks the one-year anniversary of McGregor’s death, and reminders of him are everywhere.

The Rockies have painted his initials “KSM” over purple pinstripes inside a giant baseball in right center field. Some players still have his picture on the leaflets handed out at his memorial taped to their lockers.

“I think you see it in the organization that he helped build,” catcher Chris Iannetta (FSY) said. “I think you can see it in the spring training complex that he helped build and I think you can see it off the field in the relationships that he had.”

Manager Jim Tracy said: “I think the first place and the best place to start would be take a walk through our spring training complex. In addition to the Keli S. McGregor fitness area, his fingerprints are all over our spring training complex.”

Iannetta said Colorado’s 12-4 start was directly attributable to the team’s move to spiffy new digs in the Phoenix area. No longer do the Rockies have to make two-hour bus trips between Phoenix and Tucson, where they were often forced to face minor leaguers because other teams were reluctant to bring their front-line players and starting pitchers to Hi Corbett Field.

Iannetta said the players were refreshed when the season started and had already hit stride several weeks earlier instead of having to do so in April, when the Rockies have traditionally gotten off to slow starts.

“I think it’s the continuity of the lineup, the continuity of the guys playing on consecutive days, not having to travel, and facing better pitching,” Iannetta said. “Teams were reluctant to bring their No. 1s down to Tucson, and when we played the Diamondbacks, they never showed us their starting staff anyway. So, I think we’ve benefited from that.”

Regardless of the wins or losses, “he would be proud of us because we go out there every single night and play hard and that’s all he ever asked for,” slugger Troy Tulowitzki (FSY) said.

“And I think not only on the baseball field but I think being good role models off the field is really what he appreciated and standing for the right things,” Tulowitzki said. “And in this clubhouse we have a bunch of really good guys on and off the field and that’s what he’d be most proud of.”

On Wednesday, the Rockies will dedicate a baseball field in his honor in nearby Lakewood, where he grew up.

McGregor, a former NFL tight end, had passed a physical just before spring training last year. He’d later caught a cold, but nothing that would have kept him from accompanying other team officials on a business trip to Salt Lake City.

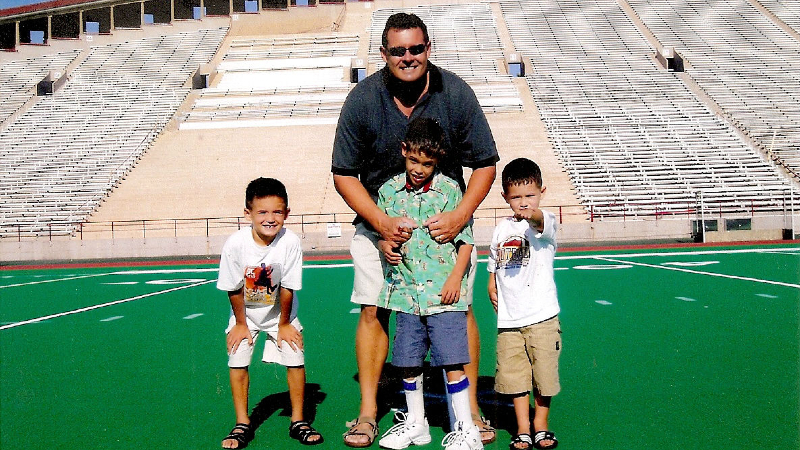

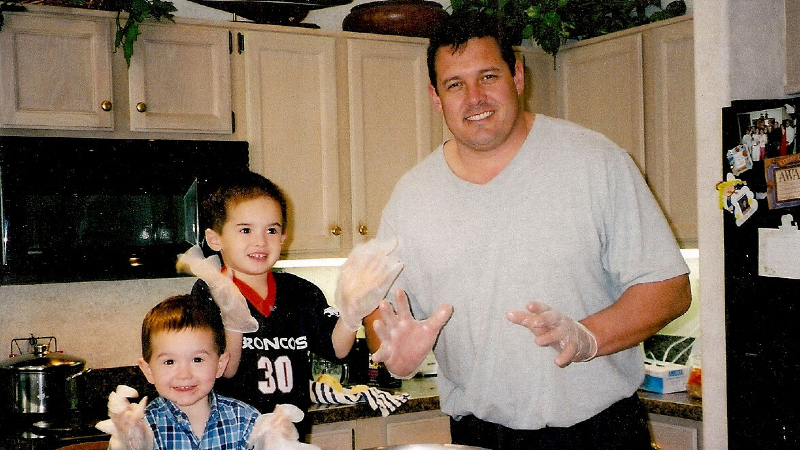

When he didn’t meet them in the lobby one morning for their flight home, police were called and found his body in his hotel room. It was later determined the father of four died from a viral heart infection.

McGregor’s loss shook the sports communities across Colorado, where he was a multi-sport athlete at Lakewood High School, starred as a tight end at Colorado State and was drafted by the Denver Broncos. He also played for the Colts and Seahawks before going into coaching and then embarking on a career in sports administration, joining the Rockies in 1993.

Commissioner Bud Selig called McGregor “one of our game’s rising young stars.”

His widow, Lori McGregor, told the Denver Post during spring training that tests after her husband’s death revealed he had a degenerative brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which causes memory impairment, emotional instability, erratic behavior and depression and eventually develops into full-blown dementia.

She said her husband suffered a couple of concussions in college and was transfixed one day when he saw an ESPN report on former NFL players suffering from debilitating depression. Although he displayed no symptoms, he wanted his brain and spinal cord donated to the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy based out of Boston University, she said.

CTE can develop when an athlete is exposed to hits that result in concussions or even as a result of repetitive nonconcussive contact, according to the center.

A cross-section of his brain was tested and came back positive for CTE, Lori McGregor said, telling the Post: “That has truly been the answer to my prayers about this, because I understand now that’s why Keli went, that’s why God took him. Because CTE is ugly and there’s no way to treat it. I really, honestly know that’s why (the heart virus) happened.

“He let a great man die a great man.”