Steve Romanik

Rocky Rosema

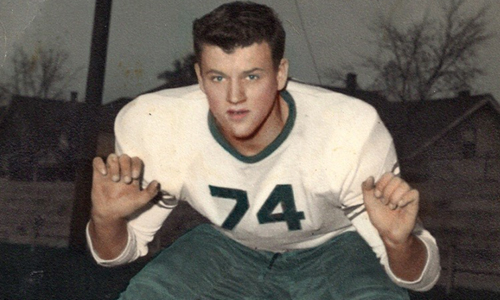

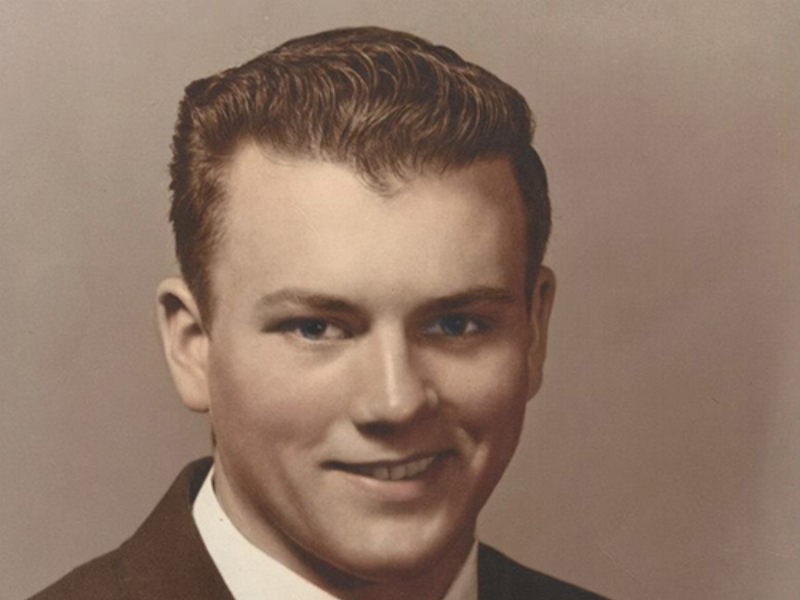

Edward Allen Roth

Edward Allen Roth was born on June 2, 1929 in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The son of Joseph and Nellie (Leiter) Roth, he was the last of four children. His parents divorced shortly after his birth and his siblings were significantly older. Growing up in the Depression Era, Ed often referred to himself as a product of the “School of Hard Knocks,” living on his own from age 14. Strappingly handsome and equally strong, Ed took an early liking to football, taking his frustrations out and proving himself on the athletic field. He also had an intense passion for music, playing various horn instruments in his high school band.

Despite his first love of music, athletics were his ticket to success. Ed earned a statewide reputation in both track & field and football as a student at South Side High School (not to mention joining the band on field at halftime). He was recruited by Bear Bryant to play for the University of Kentucky. However, his loyalty to his home state led him to play for Clyde Smith at Indiana University, where he earned his B.S. in Physical Education and was a member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity and R.O.T.C.

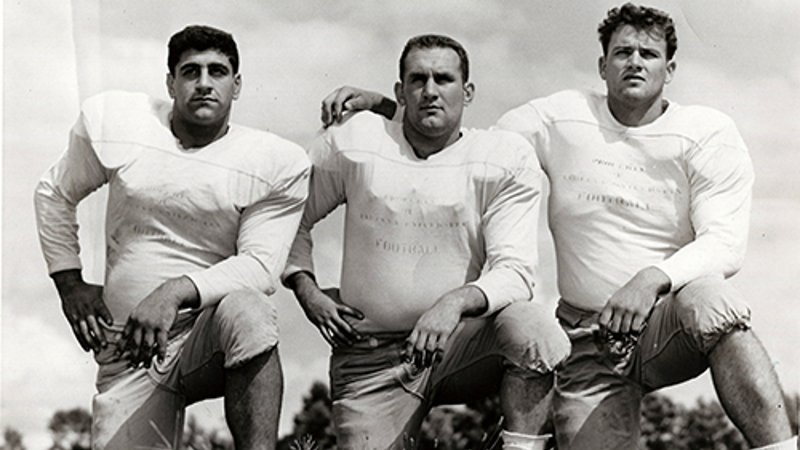

Ed lettered in football, track & field, and wrestling while at Indiana, playing offense and defense on the football team. Due to injury that kept him from playing most of his sophomore year, Ed was granted permission to play at Indiana for five seasons, allowing him to work on a Master’s degree. The highlight of his junior year was Indiana’s last defeat of Notre Dame, in which he played a pivotal role earning him accolades in the press.

Ed’s last two “senior” seasons were his most successful. In both seasons, despite Indiana not being a powerhouse football team, he was named for the All-State College First Team Offense & Defense by the Indianapolis Star and earned Honorable Mentions for both the UPI All-American and AP All Big 10. In 1952, he was named the Big 10 MVP Lineman of the Year, as well as 1st team All American “60 Minute Team” by the Chicago Tribune. At the end of the 1952 season, Ed played in both the Shriners’ College All Stars North-South game in Miami, FL as well as the Senior Bowl in Mobile, AL. Due to scheduling conflicts, he declined invitations to play in the Blue-Gray Game and the Shriners All Stars East-West Game at the end of his final college season. His proudest achievement of the 1952 nine-game season was 427 minutes played, which may still be a Big 10 and NCAA record. Unfortunately, I.U. never recognized him in its Athletic Hall of Fame, as official records were not kept of his team’s losing seasons.

In the spring of 1953, Ed left I.U. prior to earning his Master’s degree when called to serve his country during the Korean conflict in the U.S. Air Force. During his military service, he was chosen by J. Edgar Hoover to work as an international courier. He was later honorably discharged from reserve forces as a First Lieutenant.

After his active service ended in 1955, Ed played in the Canadian Rugby Union (later the CFL) for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. He had an offer to play for the Chicago Bears, but he turned it down as the Blue Bombers paid more money. However, Ed quickly realized that his prospects for injury with no long-term medical benefits were not worth the abuse his body suffered playing pro ball. After one season, he returned to Indiana to work on the Pennsylvania and Nickel Plate Railroad lines. He later served proudly as a fireman with the Fort Wayne Fire Dept. for 15 years, achieving the rank of Captain.

He met the love of his life, Rosalind Cozmas, and married her on February 5, 1961. His love of family led him to embrace Rosie’s family’s Macedonian way of life, and he was ever grateful for being accepted into the Macedonian community of Fort Wayne. Ed and Rosie had two children, Nick and Mary. While he encouraged his children to love athletics, Ed never pressured his son to play football. Despite his love for the game, he did not want his son to endure the lifelong consequences from the types of injuries he had suffered on the football field.

Ed was passionate about investing in the stock market, always willing to teach friends and family how to chart stocks and ride the waves with the bulls and the bears. He was almost never seen without his Wall Street Journal, even in the steam room at the downtown YMCA. He also loved his kennel full of hunting beagles, perhaps his greatest joy after his family during his adult years. A bit unique, Ed’s quirkiness, occasional explosive outbursts and unusual use of expletives could be shocking to strangers, but they were amusing and endearing to those who knew and loved him. He was an honest man who gave truthful advice, putting family and unconditional love first. Friends lovingly referred to him as “Big Eddie”, but to his family he was “Big Daddy”, “Poopsie”, “Dedo”, or “Papa Grande”.

Later in Ed’s life, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s-related dementia. However, as news reporting and coverage of CTE slowly grew, Mary and Nick began discussing the possibility that their father might be suffering from CTE instead. After all, throughout their lives, he had exhibited the typical symptoms of depression, explosive outbursts and organizational dysfunction that accompany the disease. However, as Ed advanced in age and lost more of his memory, his temper mellowed and his loving nature became much more evident.

Upon his death on August 3, 2013, the family was fortunate to coordinate a brain donation to the UNITE Brain Bank. The team at the Brain Bank was able to definitively tell them that Ed Roth had lived with relatively severe CTE for much of his adult life. It was a comfort and relief for Nick and Mary to understand their father with this new perspective.

Ed always preached the life lessons he learned playing football. He loved the game and the bonds it helped him forge with players he encountered on both sides of the line, but he also understood the physical toll it took on his life. A product of his persevering generation, Ed lived his life with courage, strength, and occasional frustration, sharing his love for his family and friends, as well as capitalism and country, with all willing listeners.

We are grateful to the wonderful team of Boston University doctors who interviewed and debriefed us, giving us answers to questions that otherwise would have never been answered. Nick and Mary’s only regret is their mother predeceased their father, and she did not receive the same knowledge and closure. Edward Allen Roth was a wonderful husband, father, grandfather, uncle, friend and patriot. Bog da Prosti (Memory Eternal), “Handsome Eddie”.

Max Runager

Tyler Sash

Eric Scoggins

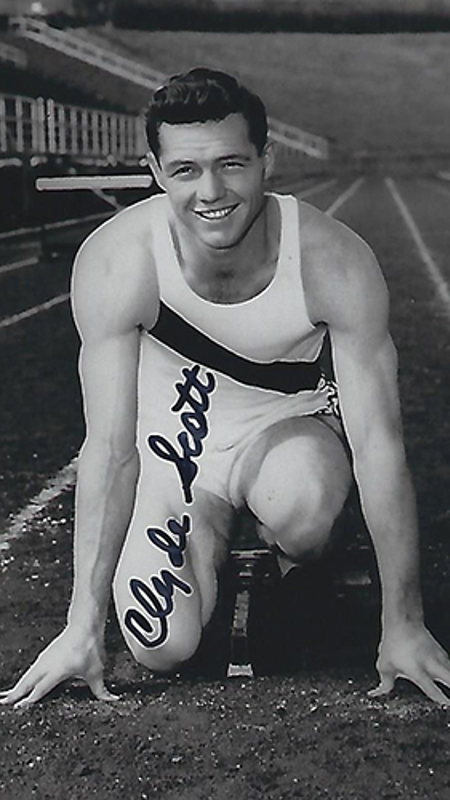

Clyde L. Scott

My father Clyde Scott was an extraordinary athlete who lived a long and productive life. He died in 2017 at the age 93 after a long battle with dementia. After his passing, we were surprised to learn that he was diagnosed with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

In February 2000, the state’s largest newspaper The Arkansas Democrat Gazette declared Clyde Scott Arkansas’ Athlete of the Century (1900 – 1999). They called his sports resume impeccable and undisputable. It is easy to see why.

Clyde was an All-American at two universities and at two sports, held two world records in track, won a gold medal at the NCAA championships, a silver medal at the 1948 London Olympics, was a first round NFL draft pick, played four seasons and was on two World Championship teams (1949 Eagles and 1952 Lions). He was considered one of the greatest athletes of his time.

Clyde was born August 29, 1924 in Dixie, Louisiana, the third of ten children. His dad was an oil field worker. Clyde first gained notoriety in high school on the football field, but he also ran track where he set a number of state records. In the summer, he played baseball which he always considered his best sport. The St Louis Cardinals offered him a contract his senior year. Clyde loved baseball but wanted to go to college.

With the help of some businessmen in his home town, he received an appointment to the US Naval Academy. He played football for the Midshipmen in 1944 and 1945 and was named a second team All-American in 1945. At the time, Navy was the second best team in the country. He also ran track at the Academy where he set Academy records in the 100 dash, 220 low hurdles, 110 high hurdles and the javelin. In 1944 and 1945, he was the Academy’s undefeated light heavyweight boxing champion.

After football practice one day in 1945, Clyde had the good fortune to meet Miss Leslie Hampton from Lake Village, Arkansas. She was the reigning Miss Arkansas visiting the Naval Academy for a tour. His roommate was scheduled to be her escort but was called away on a cruise and Clyde was asked to fill in. They met, fell in love, and decided by the end of the school year they wanted to get married. With the war having ended, Clyde made the decision to resign from the Academy. That summer he was visited by coaches from around the country including Bear Bryant at Kentucky and Johnny Vaught at Ole Miss. He was recruited to come to the University of Arkansas by head coach John Barnhill, where he ultimately decided to continue his football career. The fact that his bride-to-be was attending the U of A may have influenced his decision to join the Razorbacks.

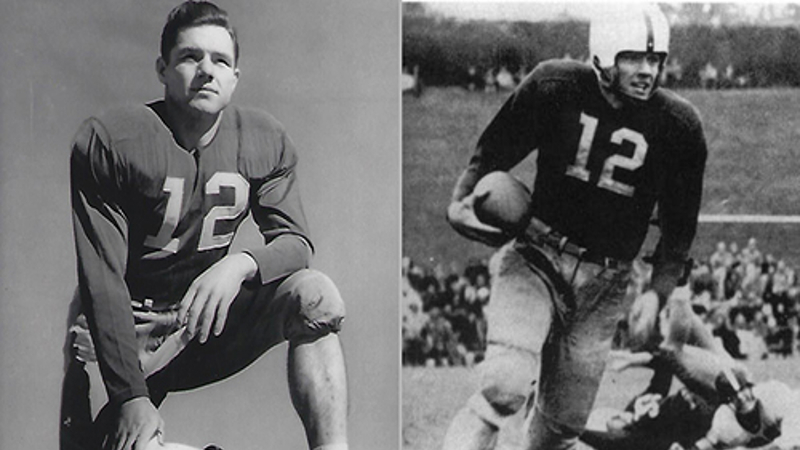

At Arkansas, Clyde was named All-Southwest Conference in 1946, 1947 and 1948, a second team All-American in 1946 and a first team All-American in 1948. His jersey number 12 was retired after his graduation. Clyde also wanted to play baseball, but his coach would not allow it. He did permit Clyde to run track where he set school records in the 100-yard dash, the 220 low hurdles, the 110 high hurdles, the 440-yard relay, and the javelin. In the 1948 NCAA Finals he tied the world record in the 110 high hurdles with a time of 13.7 seconds. That summer he made the U.S. Olympic team in the 110 high hurdles and went to the 1948 London Olympics where he won the silver medal in a very close finish.

Clyde was drafted in the first round of the 1949 NFL draft by the Philadelphia Eagles. He played three seasons with the Eagles and one season with the Detroit Lions. He battled injuries throughout his professional career and was forced to retire after the 1952 season.

Having lived such a long life, my dad would seem to be an unlikely candidate for the CTE brain study. His cognitive problems began when he was in his 80’s, much later in life than would be expected. Having a 93-year-old suffer and die with dementia did not seem that uncommon. Credit his wife of 72 years, Leslie, for making the decision to donate his brain to the study. She had seen some press coverage of the CTE study being conducted at Boston University and heard that the researchers were especially interested in brain donations from former NFL players. She realized it was an important study. After talking it over with me and my sister, the family decided to pledge my dad’s brain for research through the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank research registry prior to his death.

After his death, the efficiency of the donor program was very impressive. His brain was in Boston within the first 24 hours. Over the next several months, researchers gathered detailed information on dad’s life and sports career. You could tell that everyone we dealt with in the program was very committed to their work.

It came as a big surprise to the family that the study found dad had stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The reporting doctor said they found evidence of CTE throughout his brain which had also shrunken considerably.

Looking back, we realized there were signs that fit the CTE profile. He did not become aggressive or suffer from depression, but he did become extremely paranoid. For years, he had several irrational fears he had a very hard time dealing with. He hallucinated and had recurring nightmares. It made his life very difficult. It was also very hard on his family, especially his wife. Thankfully, the paranoia went away in the later stages of his dementia.

Dad’s mother lived to be 102 and maintained her wit and intellect to the end. His dad died of emphysema at the age of 96. There was no history of dementia in his family. How many years of meaningful life did he lose to CTE? I suspect a couple of decades but of course we will never know.

Would he have played football if he had known what may be coming? I never got to ask him that question. Football got him out of poverty, gave him an education and helped set up a successful business career, so I expect his answer may well have been yes. I do know he never encouraged me or my son to play football. Would he be glad to be part of this important study that may encourage others to avoid that dangerous path? Knowing what we know today, I have no doubt he would say “yes” to that.

Jake Scott

Charles “Bubba” Smith

Read this excerpt from Spartan Verses by Pat Gallinagh; edited by Jim Proebstle, author of Unintended Impact.

Pat and Jim were teammates of Bubba’s at Michigan State University during the 1965 and 1966 seasons, when they won back-to-back National Championships.

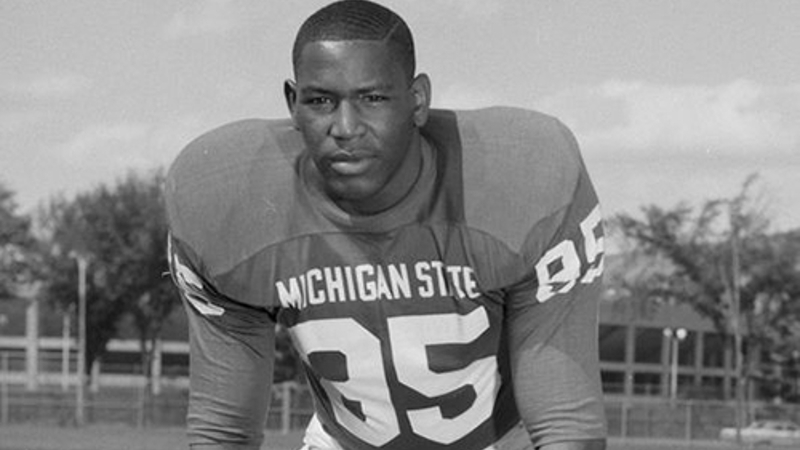

Every now and then you run into a character who is “bigger than life.” Charles “Bubba” Smith of Beaumont, Texas at 6 ft. 7 in. and 270 lbs. did both literally and figuratively fit that mold. Bubba was a passenger on the “underground railroad” of talented black athletes from the Jim Crow south that prohibited players from playing in the South. He, along with many others, was actively recruited by Coach Duffy Daugherty of Michigan State University in the sixties in what was to become one of Duffy’s hallmark achievements. Given a choice, Bubba probably would have preferred playing at a major university in his home state, like the University of Texas or Texas A&M.

By far the biggest member of the Spartan freshman football team in 1963, it was impossible for him to blend in with the thousands of new students pouring into East Lansing from all over the world. He stood out like a giant oak in an apple orchard. Many students stared at him in disbelief and rather than shy away from the fact that he was a behemoth, Bubba played the role to the hilt using his comedic talent to pretend to be a dim-witted, bumbling, good-natured oaf. A skill he would parlay into a successful acting career in Hollywood. He was a teaser and practical joker pushing his teammates’ buttons and his coaches to their limits with his pranks. In reality, Bubba was a good friend to those around him and never actively sought out the notoriety that just naturally presented itself.

There were some members of the college community who thought football players were modern day Neanderthals who dragged their knuckles on the ground as they prowled the campus. Others felt the football scholarships were a form of color-blind affirmative action for the intellectually challenged. Bubba was neither uncivilized nor stupid, although his persona did often catch the attention of the administration and coaching staff as his celebrity peaked during his senior year. The many Bubba sighting and urban legend stories that still exist to this day on the MSU campus are telltale of a man who easily adapted to the “big stage.”

With his enormous physical talent, he was often accused of not using it to the fullest on the field. There may have been some truth to that at times, but if so, it probably had more to do with peer pressure than not making an effort. When you are the biggest kid in your class you are often chided for using your superior strength and size by your classmates. Being labeled a class bully was not a coveted title back then or now, so unless prodded to do so by teammates or coaches, he sometimes may have appeared that he wasn’t trying very hard. And, it may have been because he didn’t have to. We should ask Terry Hanratty, Notre Dame’s QB who was permanently knocked out of the 10-10 Game of the Century, what he thought after a crushing tackle by Bubba in 1966. In any event, most teams ran their offense away from him as the fans in the stands chanted, “Kill, Bubba, Kill.” In the locker room Bubba was a very unique actor and just one of the guys adding tremendous chemistry and humor to a determined team of athletes.

The pros knew what they were doing when he was selected as the number one draft pick in 1967. He helped lead Baltimore to two Super Bowl performances in his five years with the Colts, winning Super Bowl V in 1971. After the Colts he spent two seasons each with Oakland and Houston. As one of the best pass rushers in the game, Bubba often drew two blockers, yet was effective enough to make two Pro Bowls, one All-Pro team and be recognized through the Vince Lombardi Trophy. Bubba Smith was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1988. The Big Ten Defensive Lineman of the Year Award bears his name. It is not documented to what extent he experienced concussions during his playing years. Clearly, there was significant punishment. What is known, however, is that the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) discovered in Bubba’s brain by neuropathologists at Boston University Medical Center was classified as Stage III CTE with symptoms that included cognitive impairment and problems with judgment and planning. Bubba died on August 3, 2011 at the age of 66. Smith was the 90th former NFL player found to have had CTE by the researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank out of their first 94 former pro players examined.

He was likely on his way to the NFL Hall of Fame until landing on a sideline marker in an exhibition game that curtailed his playing career and headed him into his acting career. Between 1979 and 2010, Bubba appeared in various roles in over twenty-two movies and television performances. Probably his most noteworthy efforts came in his role of Moses Hightower in the Police Academy movies and his role with Dick Butkus in the “taste great…less filling” Miller Lite commercials. It was this beer commercial contract that led to his proudest moment. When he realized that he was being used as an instrument to promote drunkenness; he walked away from his contract. His matured social consciousness took both strength and courage to break such a lucrative deal. He valued integrity over money. In the final analysis he was just Bubba: friendly, easy to approach, generous and never getting “too big” as a result of his success.

Bubba Smith is survived by his son, Nathan Hatton.