Timothy Webster

Ralph Wenzel

Ralph Wenzel was an 11th round pick in the 1966 NFL Draft, and played guard for seven seasons with the Pittsburgh Steelers and the San Diego Chargers, where he estimated that he suffered more concussions than he could count. After football, Wenzel went on to coach football at the college level, but began suffering from significant memory lapses and cognitive problems in 1995 at age 52. His symptoms worsened to the point that he could no longer work, communicate, or feed himself and he was diagnosed with early signs of dementia at 56. Wenzel couldn’t drive or read a book by the early 2000’s, became dependent on a caretaker by 2003, moved to a full-time facility for dementia care in 2007, and had lost the ability to walk by 2010.

While Wenzel was losing his fight with dementia, his wife, Dr. Eleanor Perfetto, was a vocal advocate for the long-term effects that her husband and other former NFL players were experiencing. By publicizing her husband’s drastic decline, Dr. Perfetto, a former CLF Board Member, was instrumental in causing the NFL to change some of its safety policies and increasing public awareness of CTE and other long-term damage. Below, Dr. Perfetto tells Ralph Wenzel’s story.

Charles White

Jesse Whittenton

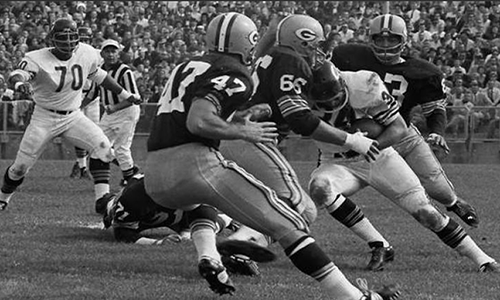

Jesse Whittenton was born in Big Spring, Texas. He was a star athlete at Ysleta High School in El Paso and a highly sought-after recruit by many college coaches. He attended Texas Western University (now UTEP) and littered the school’s record books. In the 1955 Sun Bowl, the Texas Western Miners upset the heavily-favored Florida State Seminoles thanks to a legendary performance from Whittenton.

Whittenton was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in 1956 and joined the Packers in 1958. Coach Vince Lombardi arrived in Green Bay the following season in 1959 and immediately made his presence felt.

Lombardi turned the then-woeful Packers into NFL champions in 1961 and 1962 and saw something special in Whittenton.

Lombardi once wrote Whittenton was “as close to being a perfect defensive back as anyone in the league… he can run with any halfback or receiver in the league and… he is a great student of opponents. He has studied everything about all of them, including the expressions on their faces that, when they come up to the line, may tell him something about what they are going to run.”

Whittenton was at times the perfect pupil, but at others he couldn’t shut off his jokester nature. In one of the two Pro Bowls Whittenton played in, his teammates were betting that no one would do the popular dance “The Twist” during the nationally televised game. Whittenton took the bet and twisted as his name was announced. He felt the wrath of Lombardi, who was also his Pro Bowl coach. Lombardi initially threatened to fine Whittenton $6000 for the dance, but Lombardi himself tried dancing while on vacation in Italy, realized the humor of the act, and reduced Whittenton’s fine to just $200.

Whittenton played in an era where concussions weren’t in the football lexicon. He swore he never suffered a concussion in his career, but then he would reminisce about getting his “bell rung” and returning to the game as soon as he came to.

Whittenton intercepted 20 passes in his seven seasons with the Packers, cementing his legendary status among Packers fans and his former teammates. Even decades after Whittenton retired from football, security guards at Lambeau Field would hug him when he returned for alumni weekends.

After football, Whittenton, who had taken to golf in college, returned home to west Texas and started his second athletic career as a golfer on the PGA Senior circuit. He and a cousin bought El Paso’s Horizon Hills Country Club in 1965. There, Whittenton hired a young man named Lee Trevino to serve as a bag boy for the course. A few years later, Trevino was in the midst of a Hall of Fame golf career and became Whittenton’s business partner.

After Jesse Whittenton’s football career ended, he (left) and future Hall of Fame golfer Lee Trevino (right) became friends and business partners.

Whittenton golfed every day for the rest of his life. The course was an outlet for his constant itch to be outside in the world. He was only able to sit still inside if a John Wayne western was on TV. On the course, his magnanimous personality was on full display.

“He just wanted people to be happy. He’d play golf with anybody,” said Barbara. “He didn’t care if you were a 40 handicap or you were a one handicap, really. He enjoyed it and he didn’t care.”

Whittenton always had dogs in his life, often by the same name. There were several Storm’s and always a Sheba. When a prior Sheba died young, Barbara saw Whittenton cry for the first and only time in their lives together. Whittenton got a new Sheba, who, along with Buster, followed Whittenton around the golf course like foot-tall furry caddies and slept with him at night.

In 2004, Whittenton and Barbara moved to the Sonoma Ranch golf course in Las Cruces, New Mexico. The two of them golfed and traveled together, with Whittenton still repairing clubs and helping at the course.

Five years later, Whittenton was diagnosed with throat cancer. The prospect of becoming a burden upset him.

“Why would I go through treatments when I’m going to die?” Whittenton asked his doctors.

Whittenton’s cancer treatment spotlighted his growing memory loss. He frequently forgot chemotherapy appointments or got lost during drives he’d made dozens of times.

The memory loss was so stark that friends of the Whittentons assumed it was just joking from the same man who did “The Twist” on live TV nearly 50 years earlier.

Whittenton was triumphant in his first bout with cancer. His memory continued to fade but the cancer was in remission.

He survived feeling like a burden through the first diagnosis, but he was crushed by a second terminal cancer diagnosis in March 2012.

On May 21, 2012, Barbara was in El Paso and Whittenton’s friends were scheduled to take him to an appointment. Before they arrived, Whittenton called a neighbor and instructed him to call 9-1-1 at 3PM. The neighbor didn’t wait that long.

By the time the ambulance arrived, Jesse Whittenton had taken his life. He was 78 years old.

The following day, Barbara received a call from the Las Cruces medical examiner. Researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston were requesting to study Whittenton’s brain.

“I said yes without hesitation. It was something I needed to know. I think everybody needs to know,” said Barbara.

Brain Bank researchers diagnosed Whittenton with Stage 3 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The diagnosis brought comfort to the Whittenton family. Rather than being a victim of dementia, something had caused his late-life memory loss and occasional outbursts.

At his funeral, former teammates told tales of Whittenton’s legendary kindness and humor. He was a beloved husband, father, and grandfather, as his grandchildren adored his playful spirit and ability to make them laugh.

Barbara has golfed only once in the seven years since Whittenton passed away. Sheba and Buster are her last link to the man she loved so deeply. They still sleep on his side of the bed.

John Wilbur

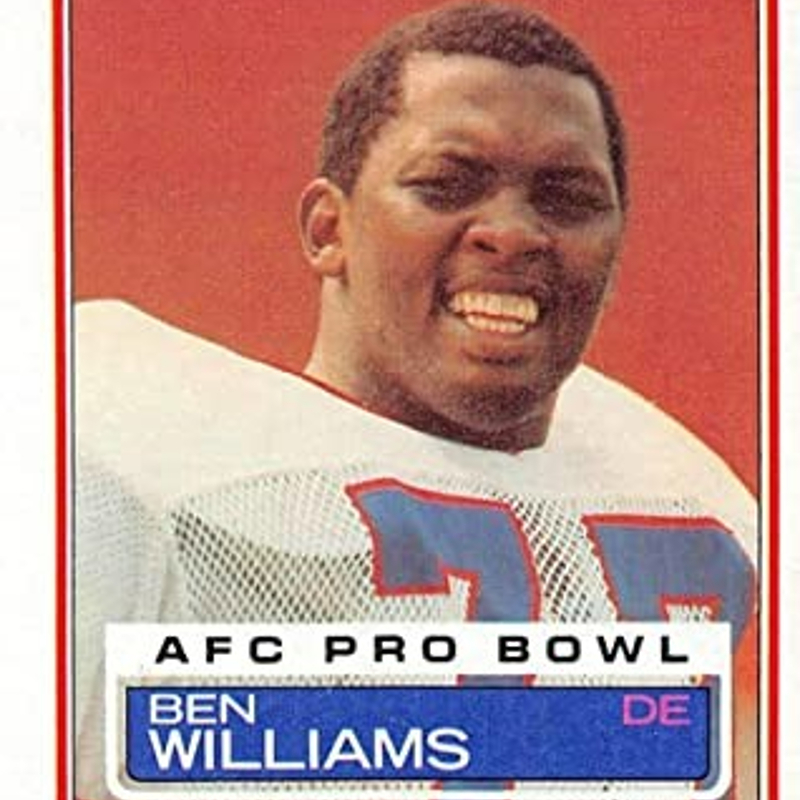

Ben Williams

“I think Ben got up that morning thinking he could cook.”

In October 2019, Linda Williams’ husband Ben Williams had just returned to their home in Jackson, Mississippi from a reunion with other Buffalo Bills alumni. Linda says Ben, 65 at the time, came back feeling like his younger self.

“He was stuck in that time period of back when he played football,” said Linda. “I couldn’t get him back. I tried to get him back, to talk about ‘now.’”

30 years earlier, Ben was the quintessential morning person and the engine of the family – often making breakfast for he and Linda’s three children and getting the family’s day started. But the Ben that woke up with intentions of making breakfast in October 2019 was no longer capable of doing much of anything by himself.

Linda woke up that morning to the sound of their dog barking, which was normal. The smoke she smelled in the hallway was not. She quickly realized Ben’s attempt to cook had gone disastrously wrong. She rushed to get them both out of their house while neighbors called the fire department. Once outside, Ben and Linda watched their house burn down.

“That didn’t faze him that much,” said Linda. “At that point, he was out of it.”

Mr. Ole Miss

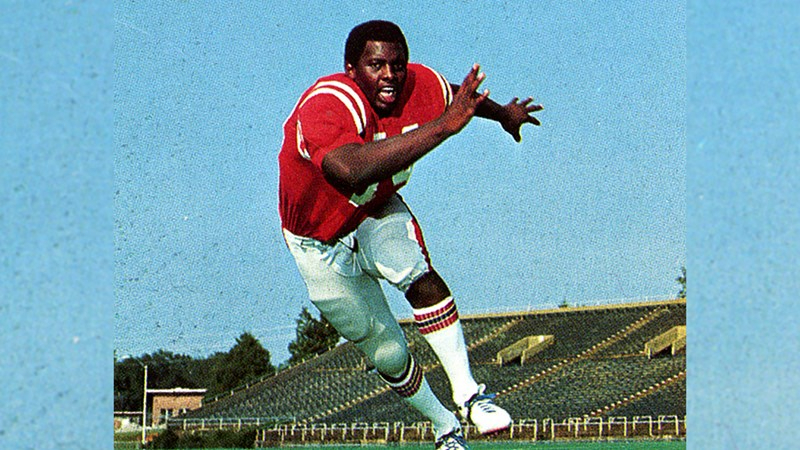

Born on September 1, 1954, Robert Jerry “Ben” Williams grew up in Yazoo City, Mississippi. He and James Reed were the first African American student-athletes to sign football scholarships with Ole Miss in 1971.

Linda met Ben her freshman year at Ole Miss. Ben showed an interest in Linda, but he was two years older than her. She was weary of upperclassmen and didn’t care about football in the slightest. But Ben’s nickname – “Gentle Ben,” after the titular character from the hit 1960s TV show – was no misnomer. She eventually gave in to his persistence and the two started dating.

“From the time I met him, he was always helping people,” said Linda. “He was very outgoing, real nice, and laughed a lot.”

Ben was a standout in every way at Ole Miss. He earned first team All-American honors as a defensive end in 1975, was elected as the first African American “Mr. Ole Miss” in school history and earned his degree in Business Administration from the school in 1976.

The Buffalo Bills selected Ben in the third round of the 1976 NFL Draft. Ben and Linda married that same year before making the nearly 1,000-mile trek north from Oxford to Buffalo.

“Dollar Bill”

Over 10 seasons in Buffalo, Ben Williams amassed 52 sacks, played in three playoff games, and was named to the 1982 Pro Bowl team. Pro Football Hall of Fame defensive end Bruce Smith arrived in Buffalo in 1985 and credits some of his success to Ben’s tutelage.

“I certainly owe a lot to Ben for embracing me as a young rookie coming into the league,” said Smith to the Buffalo News in 2020. “And not only on the field, but off the field as well.”

Ben’s work ethic made him a football star, but his industriousness was not reserved for football season. Ben returned home to Mississippi every offseason with the Bills to work for a bank in Jackson. For his off-the-field hustle, Ben’s Buffalo teammates called him “Dollar Bill.”

Ben retired from football after the 1985 NFL season. He, Linda, and their three children, Rodrick, Aisha, and Jarrett, relocated to Jackson.

Once in Jackson, Ben started his own company, LYNCO Construction. As busy as he was, Ben maintained the generous spirit he had at Ole Miss. He was very active in local charities, especially those benefitting children.

“He never did stop,” said Linda. “Anytime anybody needed something, they would call Ben and he was there.”

A Different Ben

Ben had always been easygoing and unflappable. If he ever had a bad game, he processed his frustration by watching hours of film to correct his mistakes.

But as Ben entered his 40s, his anger began to flare up. His whole life he had been the big man on campus and a beloved teammate. Little by little, Linda noticed some of his closest friends stopped hanging around as much. Later, she learned those friends had not left Ben – Ben had rudely pushed them away.

Linda experienced this new side of Ben, too. When she came home from work, she often noticed Ben stewing in anger in a way he never had before. The mood swings were so alarming and so out of character that family and friends no longer recognized the Ben they once knew.

In the next decade, Ben’s mood swings lessened, and he became more docile. As Ben mellowed, he started experiencing a new set of challenges.

Ben was struggling cognitively, and it sometimes took him days to recall the answers to some of Linda’s questions.

At this point of Ben’s life, re-living the past was much easier than managing the present. He struggled to remember anything short-term, but he came alive in conversations about his days at Ole Miss and with the Bills. He loved watching “Sanford and Son” and old John Wayne and Clint Eastwood movies – anything with a familiar plotline he could follow.

Ben’s driving became problematic as time went on. He routinely got lost on his way to events. Friends often told Linda they saw Ben aimlessly driving around town and were worried about him.

“He wouldn’t tell me he needed help because he didn’t want me to know,” said Linda. “He just pushed himself and made himself do things.”

Ben hid the full extent of his issues for as long as he could. After the house burned down in 2019, Linda and Aisha were trying to reconcile the family’s sudden financial problems – as “Dollar Bill” could no longer handle finances like he always had. They realized Ben had not been going to work every day for nearly 10 years like he said he was.

“Be Gentle”

Ben’s physical health and cognitive state eventually required full-time care. Linda quit her job to fill the role.

After the fire, many of the friends who had become strangers since Ben’s 40s soon came back around to visit. They laughed with Ben through old memories and old games. For all the joy, Linda remembers many of Ben’s old friends leaving their home in tears over the condition he was in.

In April 2020, Ben suffered a stroke and was placed in a rehabilitation center. The COVID-19 pandemic had struck a month earlier, so the family’s ability to visit him was limited to speaking to him through a glass window.

On May 17, Linda visited him in the evening. She repeatedly called his name to get his attention. Finally, Ben turned to the window, looked at Linda, and said, “Hey, Linda. I see you.”

Ben Williams died the next day.

Towards the end of Ben’s life, a group of retired ex-players in Mississippi reached out to Linda and recommended she donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank for CTE research. Linda was vaguely aware of CTE and had seen news reports about former NFL linebacker Junior Seau’s CTE diagnosis years earlier. When Ben died, she agreed to donate his brain.

Months later, researchers informed Linda that Ben had between stage 3 and stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The severity of Ben’s CTE surprised Linda. Ben had never talked about his concussion history or raised any concerns about having CTE.

“He was strong,” said Linda. “Even though he was having those problems, he was fighting it.”

Linda wants to share Ben’s story and CTE diagnosis to help explain to those who knew Ben why he may have exploded on them and alienated them years ago.

“I want the people who thought he was crazy to know that he was not,” said Linda.

Sharing his story also honors Ben’s lifelong legacy of helping others. Linda knows there are other spouses like her and other former players like Ben who could learn from their journey. Armed with the knowledge she has now, she says she would encourage spouses worried about a loved one with suspected CTE to seek professional care.

Linda also urges other loved ones of suspected CTE to pray, to practice empathy, and to remember Ben’s first nickname.

“Be gentle,” said Linda. “Be calm, and don’t fault him.”

Sam Williams

Stanley Wilson Jr.

Stanley Tobias Wilson Jr. was a compassionate, talented, and courageous man who died Feb. 1, 2023, at the age of 40. He was the blessed, beloved, and only child born from the union of Stanley Tobias Wilson Sr., and Dr. D. Pulane Lucas. Stanley was born on November 5, 1982, in Oklahoma City, about 20 miles from where his father played football at the University of Oklahoma. Stanley later lived with his parents in Cincinnati, where his father was a star NFL running back with the Bengals. Stanley would eventually move to Oakland, Calif. with his mother.

Stanley lived in the Bay Area while his mother completed her undergraduate degree. When she decided to relocate to New England to further her education, Stanley’s paternal grandparents, Henry and Beverly Wilson, became his loving and legal guardians in Carson, Calif. This move allowed Stanley to remain close to his father, relatives, and numerous friends while attending Frederick K.C. Price Christian School. At Price, at the age of 13 in the 9th grade, he was introduced to football, and he began to thrive as an athlete.

Growing up, Stanley also spent time in Boston with his mother, who was studying at Harvard University. He enjoyed serving as a ball boy for the Harvard University basketball team, attending classes with his mother, and walking around the university and Harvard Square. But a brutal winter, combined with a longing for athletic opportunities and the entertainment and holidays at his grandparents’ home led him back to Carson in the custody of his grandparents.

Upon his return, Stanley enrolled in Bishop Montgomery High School in Torrance, where he became a standout football player as a safety and member of the track team. He also performed in theater productions, served as a calculus tutor, and was crowned homecoming king.

Stanford University recruited Stanley to play defensive back for their football team from 2001-2004. As a senior, he recorded career highs for both tackles and pass breakups, earning an honorable mention on the All-Pac-10 team. Stanley also proved to be a dominant sprinter on the Cardinal track team, posting some of the school’s best results in 100 and 200-meter events. His 100-meter time of 10.46 is still the fourth-fastest all-time by a Stanford athlete.

Stanley’s peers elected him to be a senator in Stanford’s Associated Student Body. He pledged Omega Psi Phi Fraternity (Alpha Mu Chapter) and served as vice president (2003-2004). Stanley became a mentor in the Children’s Visitation Program, where he focused on inspiring youth with incarcerated parents to become positive assets in society. In 2005, Stanley graduated with a B.A. in Urban Studies.

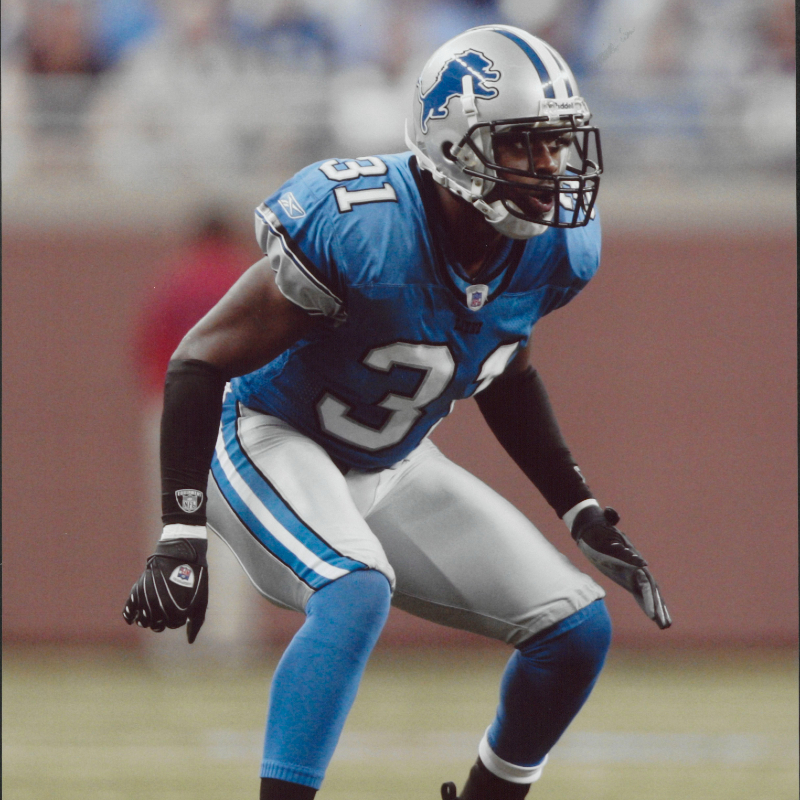

The Detroit Lions drafted Stanley in the third round of the 2005 NFL Draft. He focused on becoming a premier football player and second-generation NFL player. In 32 NFL games, Stanley Jr. racked up 86 tackles, eight pass deflections, and one forced fumble. In 2007, he was placed on injured reserve due to a knee injury, then re-signed to a one-year deal. Unfortunately, he tore his Achilles tendon during an exhibition game against the New York Giants, ending his career in the NFL.

Regardless of his situation, Stanley made time to volunteer and help those in need. From 2005-07, he was a motivational speaker, inspiring high school students to focus on education, health, fitness, and achieving their goals.

Stanley cherished spending time with family and friends, driving, reading, conducting research, and listening to music. He traveled the world, to places like the Caribbean, Italy, South Africa, Australia, Israel, and Egypt. He was an avid learner with a brilliant mind. He knew a quality education, real-world experiences, and a network of friends and mentors were critical for him as he transitioned into a successful post-NFL career.

In 2008, Stanley completed a certificate at the Aresty Institute of Executive Education and the Wharton Sports Business Initiative’s Business Management and Entrepreneurship Program. The Wharton program at the University of Pennsylvania was sponsored by the NFL and the NFL Players Association.

In 2009, Stanley completed The NFL Player Development Program: High Growth Entrepreneurship at Northwestern University. The same year, he enrolled in the Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing in New York City. He earned his nursing degree in 2014. After graduation, Stanley worked in the healthcare field in New York and later relocated to Portland, Oregon. He eventually returned to Carson to live with his grandmother.

Throughout his life, Stanley was a team player who cherished his friendships and valued his relationships with teammates and fraternity brothers. He courageously accepted new challenges with a strong faith in God and love of family. Stanley greeted each new day resilient with hope, optimism, purpose, and drive. He never stopped longing for the life that he knew he deserved.

Yet, over time, Stanley’s behavior reflected the signs of his struggles with the trauma of same gender childhood sexual abuse, mental illness, drug addiction, and indications of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a condition that links brain degeneration to repeated hits to the head. Having been deemed incompetent to stand trial, Stanley spent the final months of his life in the custody of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD). He died under suspicious circumstances.

Stanley Wilson Jr.’s family would like to thank the Detroit Lions, Stanford University, Bishop Montgomery High School, Frederick K.C. Price Christian School, and many of Stanley’s friends and teammates who have shared their condolences, kind words, and memories.