Chuck Muncie

Fulton Kuykendall

David Drachman

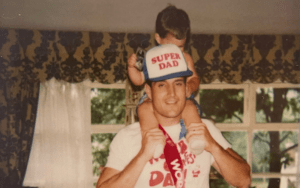

David Jay Drachman was a born winner. A wonderful husband and father, he did everything with the utmost intention and desire to be the very best.

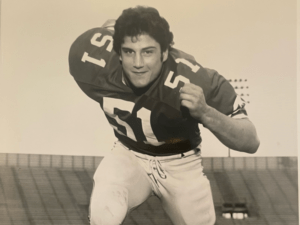

He was an All-American defensive football star at the University of Louisville, which landed him a spot in the NFL with the Buffalo Bills.

After football, David brought his energy and intense passion into the cardiovascular medical device industry. He became the first CEO of AtriCure and took the now multibillion-dollar company public, starting with just five employees. He built a winning culture wherever he went and took pride in always acting with the highest level of integrity.

Around the age of 50, David began experiencing haunting symptoms of suspected CTE. From intense pain to poor sleep, as well as mood changes, his issues only got worse. After David’s passing, we donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 3 CTE. It is our hope, as he would want, that this research can help all the other individuals & families affected by this disease.

Although David could sometimes be the most intense man in the room, he was also the most generous and giving. On behalf of the entire Drachman family, we will continue to push for safer sports, advancements in research, and pray for everyone out there who may also be suffering.

Bill Demory

An Athlete Since Youth

John William (“Bill”) Demory was born on December 1, 1950, and raised in Indianola, Iowa, the youngest of three boys. After grade school, Bill moved with his family to Phoenix, Arizona, where he blossomed into an athletic teenager, playing basketball, baseball, and football. His first known, serious head injury occurred at age 11 when he was hit in the head with a baseball – you can see a bandage above his eye in the following photo:

Bill attended Cortez High School, where one of his proudest sporting accomplishments was setting the Arizona Division 5A basketball record (which still stands) for most free throws in a single game, completing 24 of 27 attempts. His junior year, he also became starting quarterback for the football team.

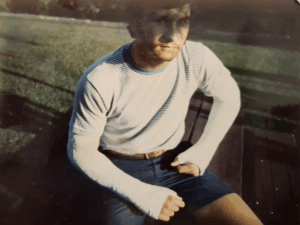

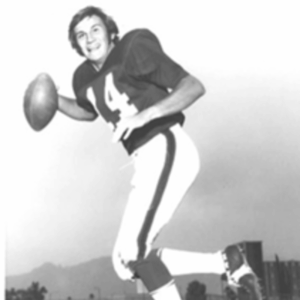

After high school, Bill earned a football scholarship to the University of Arizona, where he wore #14. In the months leading up to Wildcat football tryouts, he fractured both wrists during drills and had to wear casts on his arms to facilitate recovery. Right before tryouts began, his father cut off the cast on his right arm so he could throw. Bill would rarely tell this story, but when he did, he said his father told him, “Don’t tell your mom,” and would credit him for saving his football career.

During Bill’s sophomore year, the starting quarterback had to exit play due to a concussion. Bill made the most of this opportunity by playing well the rest of that game. From that day forward, he was the starting QB until the end of his college career.

Bill was known for his ability as a passer with a strong throwing arm, but also for his ability to pop back up after taking a big hit. Many times, his teammates wondered if he would be alright given the hit he had just taken – and yet he always stayed in the game. He remained tight knit and forever friends with many of his college teammates, who stated in those days it was a “test of manhood” to get up after being knocked down. One teammate estimated Bill suffered at least 12 concussions in college alone, and possibly many more.

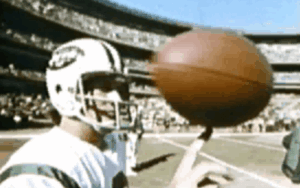

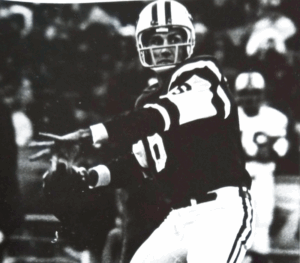

After graduating with a degree in public administration, Bill pursued a career in the NFL. Thanks to his determination and persistence, he was signed as an undrafted free agent with the New York Jets as a backup quarterback (wearing #6) to Joe Namath and Al Woodall. Due to their injuries, he was the starter for three games in 1973 and 1974.

Post Football Years and Health Decline

Following retirement from the NFL, Bill spent the next 16 years as a sales account executive, covering Iowa and Illinois. He also completed his MBA from the University of Iowa and started teaching business classes. After his four children finished high school, he furthered his education with a master’s degree in Economics for Educators from the University of Delaware and taught the subject for 20 years.

Throughout his life, Bill lived according to his favorite acronym, “Fully Rely On God” (FROG) and was active in his church and local communities. He exemplified this phrase in the way he treated not only loved ones, but teammates, friends, and students as well.

At the age of 70, Bill began having gastrointestinal issues and stomach hernias, along with the related surgeries afterward. These were accompanied by stifling, daily bouts of nausea, headaches, and hand tremors, all of which worsened over the years. On top of that, Bill was also diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. At the time, any potential connection between Parkinson’s and CTE had not yet been studied.

A lifelong athlete who played pickleball into his late 60s and rarely missed an opportunity to exercise, Bill’s physical ailments and limitations caused him increasing frustration and wore down any optimism he would find relief. Nevertheless, and despite often not feeling well, he still made time to meet friends, attend Arizona football reunions, and travel by plane to visit his children and grandchildren as much as he could.

As the Parkinson’s progressed, Bill was diagnosed with prostate cancer which ultimately was listed as his cause of death in February 2025 at the age of 74.

A Lasting Legacy

For many years while he was sick, Bill sought answers from medical professionals for his physical ailments as his Parkinson’s symptoms worsened and put a significant damper on his mobility. He knew there was a possibility all those years of playing football and accompanying concussions and repetitive head impacts could have been a factor in his declining health.

Prior to Bill’s passing, he participated in two research studies and was found eligible for compensation from past football-related injuries. He made it well known to us that his lasting legacy after death would be brain donation for CTE research, in the hopes others could benefit and learn from his experiences.

Bill’s quick-witted, dry, and sometimes caustic humor would catch those who did not know him well by surprise. But those closest to him understood the kindness behind his jokes and pranks. He never shied away from any challenge and lived life to the fullest. Bill enjoyed opportunities to think outside the box and found a way to thrive no matter what came his way, thus why his later decline in health was so devastating.

In the end, Bill pushed through these adversities and by his actions continued to selflessly support his wife, family, and friends whom he loved fiercely, and was loved just as much in return.

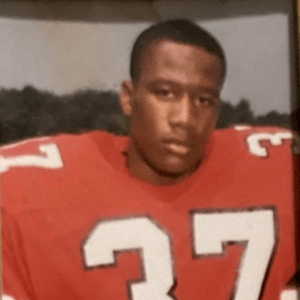

Joey Smith Sr.

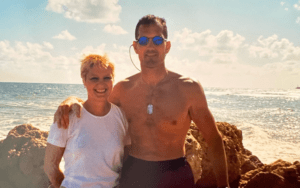

Joey Leon Smith, Sr. was an amazing son, brother, husband, father, and grandfather. His vibrant spirit and infectious smile made a lasting impression on everyone he met. Joey’s ability to make everyone laugh, his knack for fixing almost anything, and his defense of the underdog were just a few of the qualities making him a unique and beloved figure in his community.

A proud graduate of the Class of 1987 from Austin-East High School, Joey’s academic journey led him to the University of Louisville, where he not only pursued his education but also shone as a football player. His passion for the game was evident as he played with heart and skill, eventually leading him to a professional career in the NFL with the New York Giants for four years.

Joey’s love for football never waned and after his time in the NFL, he dedicated his time to coaching. He served as a defensive coordinator for both the Jacksonville Sharks and Brooklyn Bolts, and was a committed football coach at East Stroudsburg University for 14 years. Joey became a mentor for countless young athletes in their football careers and in life.

During his later years, Joey began to battle with depression, anger, and impulsiveness. He suspected his concussion history was affecting him and that he suffered from CTE. So, Joey began to write research papers on the subject. He passed away on May 21, 2024. On recommendation from one of his football friends, we sent his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank where researchers diagnosed Joey with stage 3 (of 4) CTE.

We are now sharing Joey’s story to show how CTE robbed the world of a wonderful man.