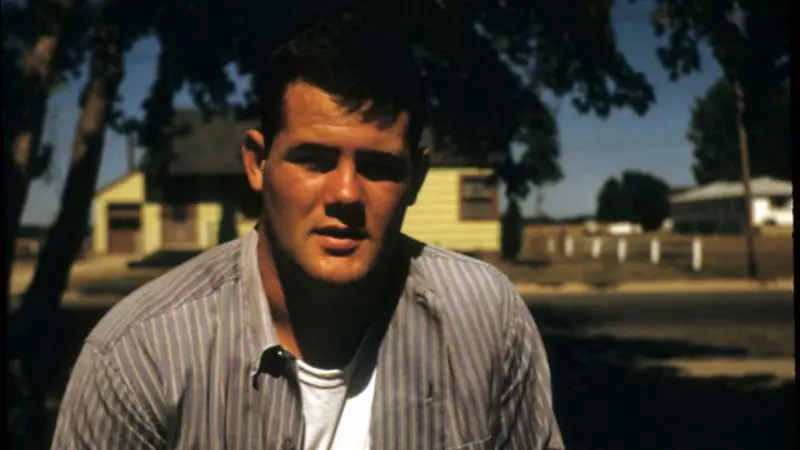

George Andrie

George Andrie was a defensive standout for the Dallas Cowboys from 1962-1972. A five-time Pro Bowler, George was a pivotal part of the Cowboys’ Doomsday Defense. George is still top-five in single-season sacks and career sacks for the Dallas Cowboys. He was a powerful star as a defensive end, and a bigger star in his personal life.

George went to Marquette University on a football scholarship. A phenomenal athlete, he had the opportunity to play basically every sport in college.

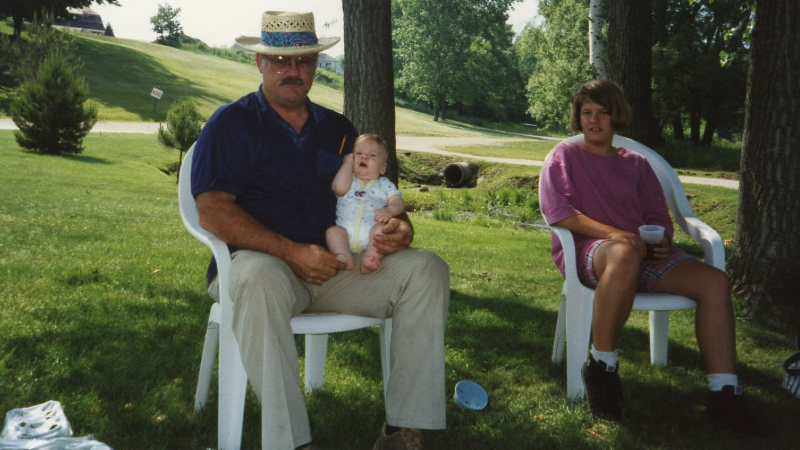

George was a man of integrity. He and his wife, Mary Lou, had seven children. They stayed together until the day they died. True love.

Dad had symptoms in the middle of his life that plagued him. He had a series of psychotic episodes, which led him to a 14-day stay in the psychiatric hospital where they diagnosed him with major depressive disorder in 2003. He shared that he heard voices and had hallucinations. Yet after thorough examinations, he was never diagnosed with any mental illness that would explain these symptoms.

But things only got worse. He got lost in his boat on the Great Lakes fishing one day, a trip he had made many times before. Luckily, he made it home as he had forgotten his cellphone. It really shook him, and he began to get very scared. He lost interest in his hobbies and became withdrawn.

He would go to the grocery store with a detailed list and forget how to get there. Then if he did arrive, he forgot he had a list. He would get embarrassed and became a person who avoided social situations where he said, “He might sound stupid.” His short-term memory was so bad that he would walk into a room and forget why he went in there.

Finally, Dad said he was going to a neurologist to answer a question he was asking himself, “What the hell is wrong with me?”

The secret no one knew was later discovered in 2019. After his death in August 2018, George’s brain was sent to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank in Boston. There, neuropathologist Dr. Russ Huber and a team of researchers diagnosed George with Stage 4 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

George’s stage of CTE was the worst, but also had progressed substantially in the worst stage.

George’s family had suspected he was suffering from CTE for four years before his death. Realizing he might be suffering from the disease helped George understand that he couldn’t entirely control what was happening to him. An improved understanding of the behavior and struggles he faced made an enormous positive difference in the relationships George had with his wife, Mary Lou, and his seven children. This awareness was possible because of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. CLF works tirelessly to spread awareness, research, and support to CTE families. We are eternally grateful to them.

When George learned about the degenerative brain disease CTE, he said he wasn’t surprised. He was especially concerned for his football comrades; those who played before him, and those who would be affected later. He became very vocal and passionate about speaking out to help others understand they were not alone in their suffering. He encouraged his family to turn his illness into positive change for others, never thinking about himself. George said if he knew football would bring him to where he was, he would have chosen differently. He said he would have been a pro golfer Instead.

Make no mistake, George and his family are very proud of his pro football accomplishments. We just wish the outcome were different, but you can’t escape reality.

George has made a difference. His voice is loud and lives on in his family. We will never stop sharing his and our story.

Thank you, Dad….. For everything…. The Concussion Legacy Foundation and your children will carry on your remarkable Legacy forever.

Peter Antoniou

Mark Arneson

Richard “Rick” Arrington

Robert Basten

Maxie Baughan

Terry Beasley

Dave Behrman

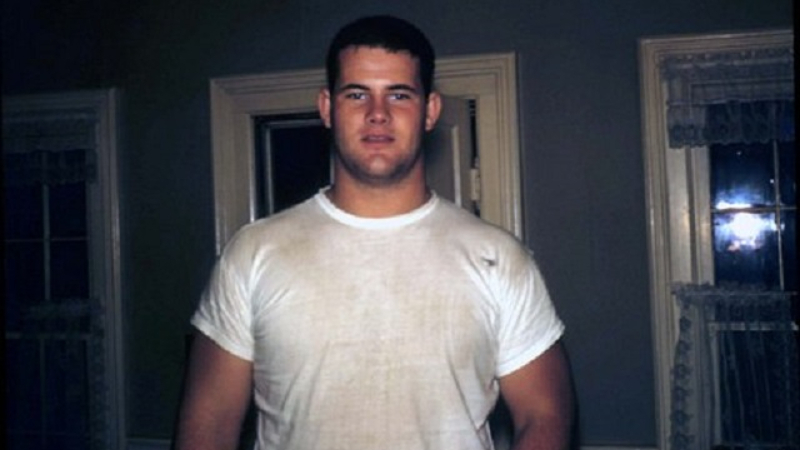

Dave Behrman and football…how good was he?

I was never an advocate of football and didn’t realize while growing up that he will forever be remembered as one of the greatest offensive tackles in Michigan State University football history. He was always big and as a 6-foot-4, 265-pound tackle he dominated opponents with his strength and quickness. MSU Head Coach, Duffy Daugherty, said that “If there is a college lineman anywhere with his speed, power, quickness, and intelligence, he has been well hidden.” Dave was an All-American pick in 1961 and 1962 and became part of the 1963 College All-Stars team that upset the NFL Champion Green Bay Packers, 20-17, on August 2, 1963 at Soldier Field in Chicago. After being distinguished as a first round draft pick in both the AFL and NFL, Dave’s AFL All-Star career with the Buffalo Bills and Denver Broncos ended in 1967 with back injuries. It was after that time period that he became a full time dad.

How do you remember your dad?

After football, he finished his business degree at Michigan State University and spent his career in the manufacturing and production environments in business and with the State of Michigan prison system tool and die shop. He loved tools and could make anything. He was a very intelligent man. At one point in my childhood my sister, Kellie, and I were wondering if he may have been one of those people who actually had a photographic memory, because he appeared to be able to retain everything he had ever read, learned or experienced. He also loved science and the value of scientific research, and I did too. He taught me that anything I ever needed to know could be found by researching it. At the same time, he taught me to pay attention to that pit in my gut, that feeling that you get when something isn’t quite right, and that the first thing that pops up might not be right, but it is the direction you go in seeking the answer.

Maybe that’s what caused him to be so good with “fixing” me. He worked with me before my ADHD diagnosis was available, without an owner’s manual, so to speak, by taking an interest in me, helping in what I was trying to do, helping to develop skills that I was good at. Since I learned by doing and not through lecture he would say, ‘don’t worry about mistakes, just make sure you learn something from them when you make them and try again.’ This is part of what motivates me today. His interest was always in what I was trying to accomplish. With my homework he simply read the chapter, looked at my assignment, and basically retaught me the lesson, one-on-one at the dining room table. Who knew just how effective that would actually be? This one-on-one fatherly touch continued when I was being punished for some teenage transgression. He would reconnect with me, alone, to discuss at length what happened, without judgement or anger, listening to me and even sharing his own personal experiences. All of those moments usually ended in some sort of agreement, often including a handshake, which I recognized as a contract that was in my best interest. And I honored every one.

Even as an adult today, one of my favorite early memories was a trip to grandma’s house and I realized that I had forgotten my baby blanket. We couldn’t go back because we had gone too far and I was not happy. My dad stopped at three stores along the way to grandma’s until we found a baby blue blanket with satin trim that made me happy. He was someone I knew I could count on.

All of this changed when the onset of his Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) began.

When did you notice that changes in him were taking place?

As he got older, his interest in his workshop at home helped him focus by being alone, just like the boating and fishing activities where he could retreat from the confusion of his mental decline and the conflict of a struggling marriage. As a natural introvert, with a talent in fixing and building things, he liked model boats and collected Karmann Ghias that he could repair and restore in his workshop. It was odd that he liked these tiny cars because he was so big and they were so small. Maybe the size of the cars represented the contradiction in his power and skill in football vs. his quiet, peaceful, and thoughtful demeanor as my dad.

Sadly, the depression, confusion, memory loss, lack of motivation, secretive behavior and balance issues, attributed to CTE, began to take over as he became more and more isolated. He lost the ability to maintain interest in friendships as well as being a devoted grandparent. We didn’t understand who he was becoming or what was happening. At times he was clear thinking in making a point and just as quickly he would lose all sense of logic and understanding of the truth. We reacted with anger, hurt and resentment and his behavior was hard on family relationships—because we didn’t know. As a result, we started professional medical support for him far too late. It wasn’t until we saw the Frontline Special, League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis in October, 2013, that we began to understand what was happening to him, but the damage was done. When he died on December 9, 2014, he was diagnosed at the Boston University Medical Center for CTE with Stage III/IV CTE dementia.

How do you think about football as a result of your dad’s condition?

My dad never wanted my son, David, to play in the youth football programs in grade school. When he called me about the possibility of his playing, his advice was for David to pursue dog training or work related to animals. My dad didn’t eat, drink and sleep football like some athletes do—it wasn’t his passion. For me he was quiet, principled, shy and liked being by himself. It was sad to lose him to this disease (CTE). Knowing what I know now about my dad, I’m not so much in favor of football. I’ll admit that I don’t really understand the sport all that well and appreciate the fact that some people may disagree with my thinking.

© 2016, James Proebstle

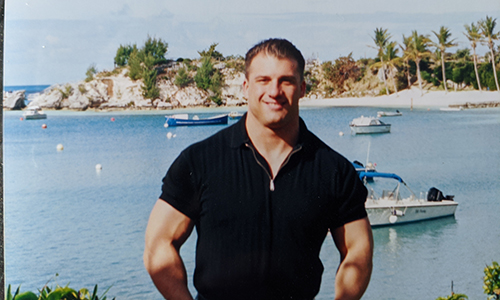

Wes Bender

Wes Bender had a kind heart. He would take the time to speak with anyone and share his experiences and challenges.

Wes started playing Pop Warner at the age of six and was passionate about football. The very first time he took a handoff, he ran 80 yards for a touchdown. Wes was smaller than the average kid, but overcame that challenge with his speed.

Wes was bright but sometimes his words and numbers were scrambled. His teachers, coaches, friends and family helped him until a key teacher recognized he had dyslexia. At the time, learning disorders like dyslexia weren’t common knowledge. Still, Wes overcame this challenge thanks to programs to help dyslexic students.

By the time high school rolled around Wes began to emerge with uncommon size, speed, strength, smarts, and competitiveness. The results? A powerful offensive running back who started as a freshman and sophomore at Burbank High School in southern California. But at the start of his junior year, the coaching staff wanted to move Wes to the offensive line. The proposed switch challenged his dream of being a college running back so he transferred schools to the cross-town rival, John Burroughs High.

Wes’ transfer to John Burroughs produced one of the most productive high school offenses in Southern California history. Against his old team, Wes scored a 50-yard touchdown run in a 41-0 victory. Wes’ success led to his induction into the John Burroughs Hall of Fame in 2015.

Dyslexia made it difficult for Wes to learn a foreign language, a college requirement. Many colleges were interested and offered scholarships, so he attended Glendale Junior College to refine his skills. Wes went on to set several Glendale College records and lead his team to win the Western State Conference title. His time at Glendale earned him a full athletic scholarship to play for the only college he would consider, the University of Southern California.

Wes started for two years at USC and set several weightlifting strength records that still stand posted in the weight room today. Wes was a powerful, hard-hitting fullback, routinely stuffing linebackers at full speed, blocking players in the open field, knocking them to the ground, and creating holes for the tailbacks to follow.

Mazio Royster was the tailback who benefitted from Wes’ blocks at USC.

“Wes was a great teammate, but an even better person,” Royster said. “It was my job as the tailback to read the fullback’s block. These were some of the most violent collisions imaginable and Wes never shied away from contact, complained, or even asked for praise.”

Wes’ incredible blocking earned him a shot in the NFL. Marty Schottenheimer, then head coach of the Kansas City Chiefs, said Wes was one of the best blocking running backs he had ever seen come out college.

Wes accomplished his dream to play in the NFL with the Chiefs. Wes earned the nickname “Fender Bender,” delivering crushing hits, knocking out All-Pros and Hall of Famers while team members would joke and tell him to tone it down a bit. An ankle injury sidelined him that year, leading him to his hometown Los Angeles Raiders. Wes was referred to as “Bam Bam” with the Raiders, receiving game balls and Monday night honors until he moved to the New Orleans Saints two years later.

New Orleans was Wes’ final stop in the NFL. He played for the “Coach” Mike Ditka. Coach Ditka preached tough, hard-hitting football. Wes was at home in New Orleans, winning more game balls, and creating key plays with his blocking.

Wes’ position and style of play led to countless head impacts. He suffered a reported 23 concussions in his football career. He retired from the NFL in 1997.

The football chapter of Wes’ life was closed, opening the door to the business world. Wes always loved to modify cars and trucks, so he started a successful business building modified four-wheel drives and other auto specialties. Wes was very good with people, had a kind heart and would chat with anyone. One of his clients thought he might enjoy the sales and service elements of the concrete business.

Wes was very successful running large concrete jobs in Los Angeles, but some things in his life were not clicking fully. Sleep became more challenging, as Wes would wake up frequently at night. He became overwhelmingly stressed by simple things most people can cope with easily. The concrete business was very competitive, stressful, and becoming too much for Wes, so he decided to retire from that business due to health concerns.

The final chapter was starting a business with family in the medical and dental industry. This was perfect, helping the business get started at his Alma Mater USC and crosstown rival UCLA. The UCLA dental program loved Wes, despite him being a USC alum.

Wes could always make you laugh and could remember movie lines from 30 years ago or jokes from childhood. But he strangely couldn’t remember what he had for dinner the night before, or a conversation he had with a salesperson a week ago about training.

“What was going on?” we’d ask Wes.

Wes would get frustrated and say, “I just can’t remember.”

Simple tasks, things most people don’t think about became a challenge. Wes would run to the store to get milk and then forget why he went to the store.

My brother Wes passed away in his sleep on March 5, 2018 at age 47. The stress of his life was too much for his heart and his brain.

Four months before his death, Wes completed his will and stated his intention for his brain to be studied at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston. At the time, we thought this was an interesting decision, but we followed his request and sent his brain to the Brain Bank.

There, researchers diagnosed Wes with Stage 2 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). We didn’t know it at the time, but Wes’ intuition about his brain was correct.