Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

A Bright Light Dimmed too Soon

When I think of Alyssa, her eyes come first: light brown, luminous, and always scanning the world with empathy and curiosity. Vintage vibes, Crocs style. Sharp, witty, and wise beyond her years, she saw people deeply, even as a child. Her kindness wasn’t a choice; it was instinct. She didn’t perform goodness; she embodied it. She was sharp, too; quick with a comeback, clever in a way that made you laugh and think at the same time. She saw people—really saw them—in a way most adults never learn to.

Even as a toddler, Alyssa carried herself like someone who understood the world in ways other kids haven’t even begun to notice. I remember once, running late to feed her, bracing for a meltdown. Instead, there she was, looking up at me with quiet patience and a half-smile. No drama, just grace. That was Alyssa.

We used to ride bikes together. She’d fly ahead, wind in her hair, but always stopped at intersections to wait until I caught up. We’d talk about school, about life, about how lucky we were to be surrounded by beauty, even on the hard days.

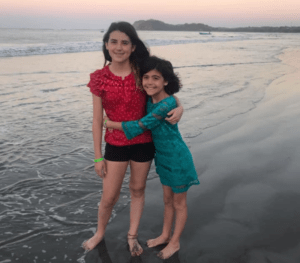

Alyssa was a natural athlete. Her first love was skiing, starting at just two and a half years old. She seemed born to fly down mountains. People from outside Colorado might think that’s crazy; those who live here know it’s not. She adored bundling up in layers alongside her younger sister, Emily—long underwear, wool socks, puffy suits, mittens, ski boots, and helmet. Alyssa skied on a local team and raced in the Nighthawks Series at Eldora, a small and notoriously windy ski area near Arvada. Eldora is known to locals as “Helldora” because of the icy conditions, but Alyssa embraced it. Under the lights and racing in the dark, she seemed to shine even brighter.

Alyssa also picked up mountain biking, skateboarding, and any other activity that screamed Colorado adventure. But it was soccer that truly captured her heart.

It was easy to see something click in Alyssa the first time she stepped on the field. She was four years old in tiny cleats, dancing through warmups pretending to be a kitty. By age ten, she was juggling the ball more than 100 times in a row. People would stop and film her in the park. No music, just her own rhythm. Neighbors would shake their heads in amazement and tell me, “That girl is going to be something.”

But Alyssa wasn’t just physically talented. She had wisdom and innocence that made her stand out. She played competitively, took private lessons, attended winter and summer soccer camps, and trained year-round. She set goals, writing them on her hand or the nearest napkin. Her ultimate dream was to go pro, then eventually become a coach. Our lives revolved around practices, matches, and tournaments. Alyssa loved every minute of it.

Changing Behavior

Around age 13, something began to change in Alyssa. At first, we chalked it up to adolescence: moody days, quiet withdrawal, the normal turbulence of a notoriously hard age marked by hormones, identity shifts, and social pressure. Looking back, I believe undiagnosed concussions may have played a much larger role in her mental health than we realized.

Throughout her childhood, Alyssa had several significant head impacts, from ski racing crashes and mountain biking spills to a poolside accident where she hit her head jumping in too close to the edge. Add in the frequent collisions from years of youth competitive soccer and practicing heading the ball, and the pattern becomes hard to ignore.

One of the most serious incidents happened when Alyssa was 11, ski racing in Glenwood. She hit a rut and crashed hard, landing headfirst and striking the right side of her head before sliding into a gate. She was wearing a helmet and stood up quickly, ready to keep skiing, but the dizziness and nausea came on fast. We took her to the hospital that morning.

At the time, I didn’t connect Alyssa’s physical injuries to her emerging emotional shifts. I didn’t realize concussions can quietly stack up, especially in the still-developing brain of a child. As I later poured over her medical records, I found times we hadn’t sought medical care after a fall. She was tough and wanted to keep playing, so we let her. We truly believed she’d be fine.

After Alyssa died by suicide in November 2019, I was desperate for answers. I devoured every mental health article I could find, spoke to those who knew her best, and examined every corner of her life. I even wrote a book, hoping somewhere in the pages I’d uncover clarity or closure. What I found instead was laughter, brilliance, beauty, and a million reasons to be proud, but no definitive answers. Alyssa didn’t have access to social media. She thrived academically. She was deeply loved and supported at home. I thought I was doing everything right, but I missed the quiet signs—her heart and her brain were hurting.

We lost Alyssa at just 13 years old. That sentence breaks me every time I speak it aloud. Even the detective assigned to her case said she was one of the most honest children he had ever encountered. Her teachers, friends, and coaches were equally stunned. There was no obvious trauma. No warning sign that screamed for attention. No clear reason.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, suicide is a complex public health concern, and there is no single cause. Suicide is exacerbated and most often occurs when stressors and health issues converge to create an experience of hopelessness and despair.

Here is what I do know: even in her pain, Alyssa remained full of love. She adored animals. She stood up for those who couldn’t stand up for themselves. She was kind, artistic, hilarious, and endlessly imaginative. We were, and always will be, unbelievably proud of her.

Grief is a strange, disorienting fog. You stumble through memories. You question everything. You try to make meaning from what feels like senseless pain. And in that process, you realize that maybe—just maybe—your story, your child’s story, can save someone else.

Advice for Other Parents

We now believe it’s possible Alyssa’s brain could have been injured—repeatedly and invisibly. Some of her symptoms align with what we now know about traumatic brain injury (TBI), post-concussion syndrome (PCS), and the long-term effects of repeated head trauma in youth sports.

TBI and concussions can lead to depression, anxiety, memory issues, and emotional instability. For teenage girls already navigating hormonal swings and social pressure, the impact can be devastating. And unlike a broken bone, brain injuries don’t show up on an X-ray.

If you’re a parent, please listen to what I’ve learned through the heartbreak of losing my daughter, Alyssa:

- Take every head injury seriously, even those which seem small.

- Advocate for baseline concussion testing in your child’s sport. It can make all the difference.

- Watch closely for changes in mood, not just changes in performance.

- Believe your child when they say they feel “off,” or anxious, or just not themselves.

- Ask the hard questions and have conversations even if they feel uncomfortable.

If your child’s joy starts to dim, don’t wait. Early intervention could save a life.

Alyssa’s legacy is one of empathy, courage, and kindness. We share her story not to scare others, but to awaken. Every parent who speaks up, every coach who learns, and every child who is protected keeps her light burning.

Because Alyssa, even in her quietest moments, gave us hope.

And it’s that hope we hold onto now.

For her.

For Emily.

For every family.

________________________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.