Chris Benoit

Richard Byrne

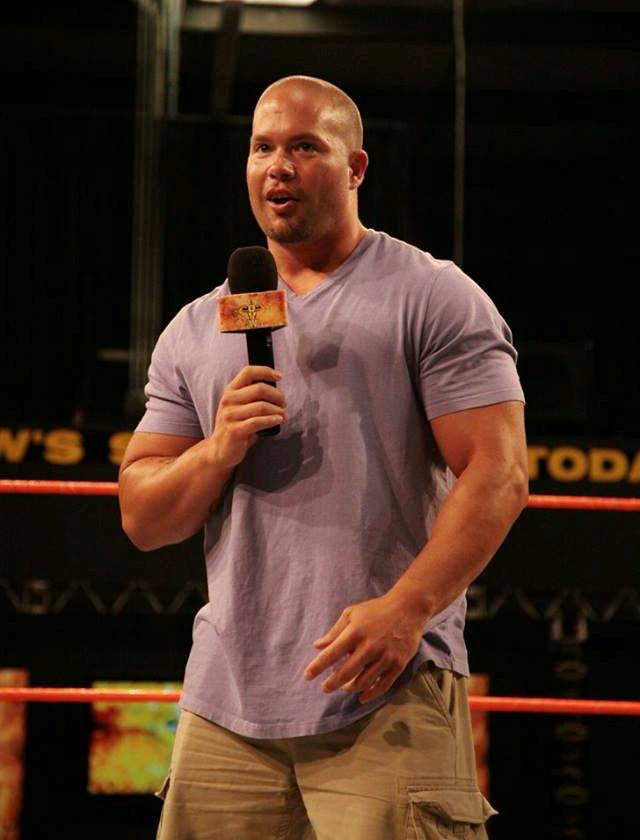

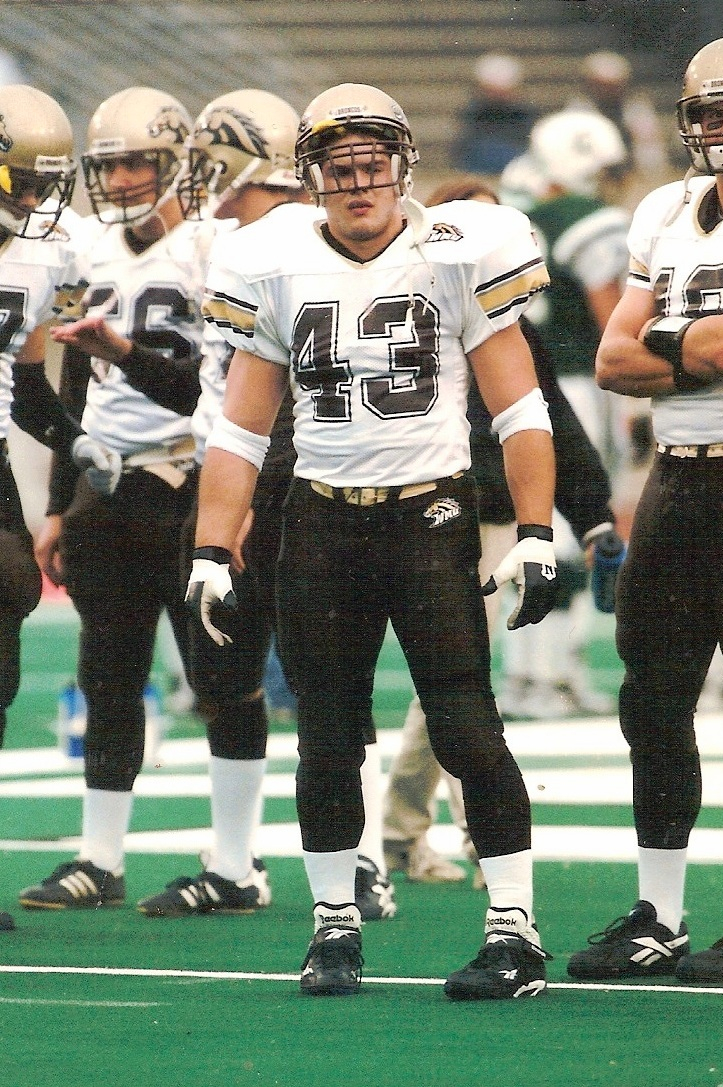

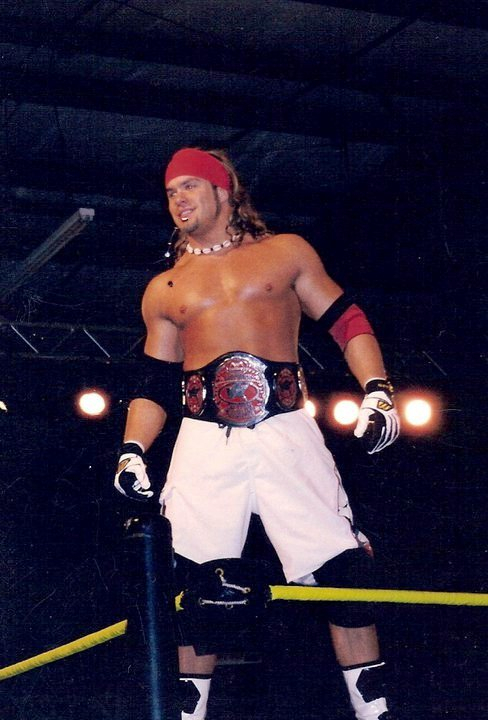

Matt Cappotelli

Matt grew up in the small town of Caledonia, New York, which was a huge football town. His dad owned a gym and had him start lifting weights at a young age, something he loved and continued for the rest of his life. He started playing football in 8th grade and quickly became a star player. Matt had a great work ethic and was an amazing athlete, but he was also smart, witty, funny, outgoing, humble, and kind. He was known in his town and high school not only as a terrific football player, but for his humility and caring personality. Matt was a Jesus follower, and you could see that in the way he loved and interacted with people.

Matt continued playing football throughout his first couple of years of college at Western Michigan University, until he had to stop playing due to knee issues. This was when he decided to audition for Tough Enough, a reality show on MTV where contestants competed to win a contract with the WWE as a professional wrestler. Matt had been a wrestling fan since he was a little kid, growing up watching wrestling on TV with his dad. He ended up winning the show and was then sent to Louisville, Kentucky, to train at Ohio Valley Wrestling before being put on TV. That’s when I entered the picture.

Ohio Valley Wrestling (OVW) held a live weekly show on Wednesday nights that I would occasionally go to with friends, and we ended up meeting there after one of the shows. I knew who he was from watching Tough Enough a few times, and I was instantly drawn to him because of his strong faith. After our first date, I knew he was “the one” and that I would marry him some day.

We dated for two years, during which he continued to train at OVW, as well as occasionally travel to shows with the WWE. Matt’s dream was to become a WWE Superstar, not only because he loved to entertain and perform, but also to be a positive example for Christ in that industry. He was on the verge of his dream becoming reality when he discovered he had a brain tumor. It was one week before he was set to debut on Monday Night Raw.

Incredibly, Matt had no symptoms and only discovered the tumor after being knocked unconscious in the ring during an OVW match. He was sent to the hospital to get checked out, which was when they discovered the tumor. After a biopsy, Matt was diagnosed with stage 2 brain cancer. We got married on the beach in Hawaii two months later.

Unfortunately, with the cancer diagnosis, Matt had to put his dream of becoming a WWE Superstar on hold. In 2007, he had surgery to remove the tumor, and then did six weeks of proton radiation, followed by oral chemotherapy for the following two years. From that point on, he had MRIs regularly and the scans were clear for the next 10 years.

We had an amazing 12-year marriage, and I’m so thankful for those cancer free years I got to have with him, living life to the fullest. From our beach trips, to cruising in the Jeep on summer nights, our pizza and putt-putt dates, and even just our boring nights chilling on the couch at home, every day with him was fun. His smile and laugh were the joy of my days. I thanked God every single day for sending him to me. I never imagined the tumor would come back and naively thought his fight with cancer was over. Little did I know; the worst was yet to come.

Exactly 10 years after his first brain surgery, an MRI showed the tumor had grown back. I’ll never forget the day I got that call and heard those words come from his mouth – my worst nightmare had come true. Two days later, Matt had surgery to remove as much of the tumor as they could from his brain. About a week later we got the official diagnoses: Grade IV glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the worst and deadliest form of brain cancer. The prognosis for GBM is not good, and we were told that even with treatment, the average life expectancy is around six months.

Matt underwent chemotherapy and also used a device called Optune, a fairly new form of treatment for brain cancer. Unfortunately, the treatments couldn’t keep the tumor from growing, and he continued to decline as the months went by. Watching my strong, outgoing, energetic husband slowly deteriorate was the worst thing I’ve ever been through in my life. He passed away exactly a year after his brain surgery on June 29th, 2018.

I knew Matt wanted to donate his organs, but because of the cancer he was unable to do so. He couldn’t speak towards the end, but I just knew he would have wanted to do something to help others in some way. Then I remembered his interest in CTE. During Matt’s time with the WWE, he became friends with Chris Nowinski and learned of the work he was doing to advance concussion and CTE research.

Matt was committed to CTE research as someone who had suffered multiple concussions in the past through football and wrestling, and someone who always wanted to help out a friend in any way he could. When he had his tumor removed in 2007, he reached out to Chris and coordinated sending the brain sample to Boston and the UNITE Brain Bank, just in case they could learn something from some of the healthy tissue that was removed. He did the same thing after his surgery in 2017. When we lost Matt, I knew he would have wanted his brain donated to help further CTE research. So that is what we did. He is the first person to have his brain tissue studied for CTE while he was alive and after he passed away.

While Matt had no obvious symptoms of CTE I saw during his life, it’s hard to really know because of the enormous changes his cancer caused. He did suffer from mild seizures or partial seizures, as they’re called, for the last two years of his life. Around the same time, he was also diagnosed with Parkinsonism, which is a neurological disorder that has many similar symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, such as slow movement, speech and writing changes, and muscle stiffness, among others. I noticed some of these changes a few years before he died, as well as some slight personality changes over the last few years.

When we got the results back from the donation, we learned he had been diagnosed with CTE, as well as Parkinson’s Disease. I found myself a bit emotional after hearing the diagnosis, and it explained a few things for me. Now I know that along with everything he dealt with from his brain cancer, he may also have been experiencing the early stages of CTE’s effect on his mood, memory, and thinking. Despite all of this adversity, he handled it like a champ, always stayed positive, and never complained.

The most common thing people say about Matt is that he was one of, if not the BEST, person they knew. He impacted countless lives. There was something about him – his smile, his laugh, just his presence, that drew people to him. More than that though, I think it’s because of the way he genuinely cared about others and how he made everyone he met feel important, no matter who they were. He made everybody feel like a somebody. He loved helping others and making people laugh. I think he was happiest when he was putting a smile on someone else’s face.

Throughout all of his injuries and health conditions, and even after two brain surgeries, chemo, and radiation, he never complained or felt sorry for himself. He never let it get him down. He was still always looking out for others and always laughing and joking around, even at the very end of his life. That was just Matt. I know he was disappointed that his dreams of becoming a WWE superstar didn’t become a reality, but he didn’t let it get him down. He continued to trust God’s plan and made the best of where He put him. He continued to help and inspire others, even if it wasn’t in the wrestling ring. All he wanted to do from his initial diagnosis of brain cancer in 2006 was to help and inspire others with his story and to point them to Jesus, and my hope is that his story will continue to do so. I’m thankful for the Concussion Legacy Foundation and that Matt was able to play a role in advancing the research and awareness of CTE, which I know is what he would have wanted.

Joseph Chernach

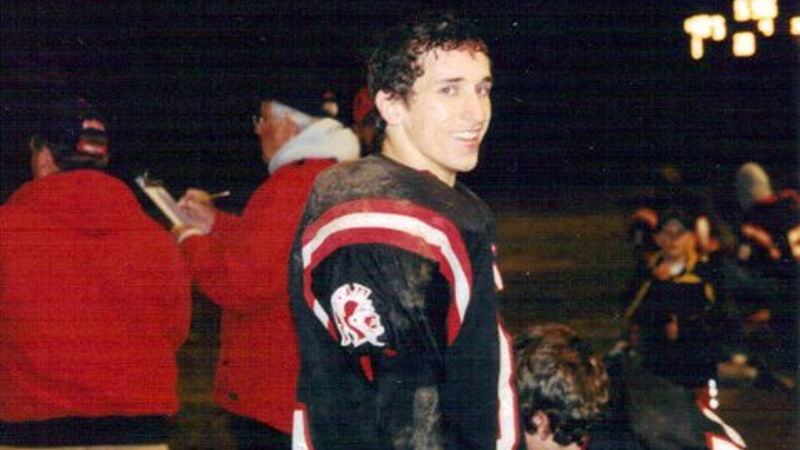

Joseph Chernach traveled to his next journey on June 6, 2012. With his Forest Park Trojan and Green Bay Packer jerseys, his difficulties and struggles with depression finally came to end at the age of 25.

Joseph was a competitive and talented athlete from an early age, playing summer baseball, wrestling since the age of six and throughout high school, a pole vaulter in track, and pop-warner, JV and Varsity football in high school. He won many medals and trophies from grade school through high school.

He was the Michigan High School Upper Peninsula pole vault champion, Michigan High School state wrestling champion, named all U.P class D defensive back, all State class D defensive back, MVP of football along with senior athlete. He was proud to play in the Michigan High school state football finals in 2004 with the Forest Park Trojans.

His greatest accomplishment was graduating with high honors from Forest Park High School in 2005.

He also attended Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan with plans to graduate with a degree in Physical Therapy.

Joseph was baptized at the Northfield Lutheran Church, Hixton, WI, and confirmed at the United Christ Methodist Church in Crystal Falls, MI. His Facebook page reflects his religious views as “God Loves Me.”

Joseph was fun, active and lived for making people laugh and his sense of humor touched many. He was a fan of the Michigan Wolverines, Milwaukee Brewers and Green Bay Packers. He loved to fish and deer hunt in Wisconsin on the family farm.

Joseph leaves behind many family and friends, father Jeffrey Chernach, mother Debra (Fred) Pyka, brothers Tyler (Michelle) and Seth, sister Nicole, step-sister Samantha, Grandmother Lolly, nieces Braylee and Layla and the Forest Park Class of 2005.

A yearly scholarship has been set-up in his memory.

Joseph Chernach Memorial Scholarship

Forest Park High School

801 Forest Parkway

Crystal Falls, MI 49920

In Joseph’s final few years, he suffered with depression and unable to overcome all the struggles and difficulties with life. CTE was destroying his brain until he could no longer go on with life here. Looking at his headstone in the cemetery is very heartbreaking knowing he is gone. We will never see him graduate college, marry, become a father, and live a happy, healthy and successful life.

We will always wonder what he would have accomplished in his lifetime and we know he will be waiting to see us all again, until that time comes, we are left with the devastation of losing him and living our lives without him. We are all grateful for having him in our lives for almost 26 years. Until we meet again, our love goes with you and our souls wait to join you.

For almost 20 years, the NFL covered up and denied evidence to the connection between brain damage and football. How many people have died from this brain disease whose families are unaware? How much progress could have been made for research, a cure, and the safety and health of everyone had this evidence been made public 20 years ago?

I have contacted the news media, local congressman, senator, representative, the National Federation of High schools and the White House with my son’s story and concerns with sports, head trauma and CTE. The safety and health of our children are at risk. I hope someone will finally listen.

We love you and miss you Joseph and we’ll all be together again one day soon.

We are grateful to the Concussion Legacy Foundation for the research and diagnosis to finally give us the answers to what caused Joseph’s depression and early death. Joseph never played college or pro-sports and we do not know of any concussions during his middle or high school years. This is the report we received from Dr. Ann McKee at the BU CTE Center in December 2013:

“Fixed tissue samples were received from Sacred Heart Pathology Department, Eau Claire, Wisconsin on 9/6/12. There were no obvious abnormalities. However, microscopic analysis of the tissue revealed considerable pathological tau deposits as neurofibrillary tangles throughout the frontal brain regions. There were also very severe changes in the brainstem, with numerous tau neurofibrillary tangles in the locus coeruleus, an area of the brain thought to play a role in mood regulation and depression. The changes in the frontal lobes and locus coeruleus were the most severe I’ve seen in a person this age. These findings indicate Stage II, possibly Stage III (with Stage IV being most severe) CTE and are particularly noteworthy, given the young age of the subject.”

Read more about Joseph and his story from his parents and BuzzFeed News.

Jared Crippen

This story adheres to the Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide from reportingonsuicide.org

Laura Lowney entered her son Jared’s room in Brick, New Jersey, at 6:00 a.m. on the morning of April 23, 2019. He wasn’t there. This had happened before. Jared could be any number of places. He could be lifting at the gym. He could be surfing. He could be at the lacrosse fields. But an ominous feeling told Laura something was very wrong.

The night before, Jared had left to go to a party. He returned late that night and went to Laura’s room to say goodnight. Jared was 16, popular, handsome, and athletic, but he was never ashamed of how much he loved his mother. He hugged her tight, then bent down at the foot of the bed to kiss the family cat, Nala. Jared came back and hugged Laura again.

“I love you mom.”

“You seem mellow, Jared. Are you okay?” Laura asked.

“I’m okay. I’m just tired,” Jared said as he left the room.

Golden Boy

Born on December 6, 2002, Jared Crippen was special from the start. Baby Jared was constantly smiling. Tantrums were not in his repertoire.

Jared’s teachers found him adorable and appreciated his work ethic and infectious energy. He got along with everyone, worked hard, and thrived in school.

Jared was also naturally athletic. He got on a surfboard and balanced himself in a lagoon for the first time in fifth grade. Twenty-four hours later he was riding waves. In just one day, a lifelong hobby was born.

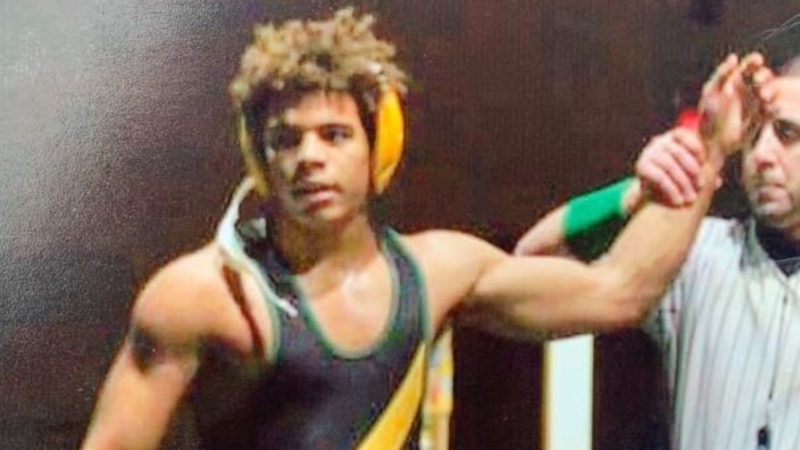

Jared wanted to wrestle and play lacrosse. Jared pleaded to follow in his older brother Jaden’s footsteps as a wrestler, but Laura held him out of competition until sixth grade. Once he started his strength, coordination, and speed allowed him to excel in both sports. As a freshman at Brick Memorial High School, Jared made the varsity wrestling and lacrosse teams.

Jared reached the regional championships for wrestling while competing against juniors and seniors. College coaches took note of his athletic ability.

“He was a caring friend and teammate. He had that ‘it’ factor. I could feel it. People were attracted to him,” Jared’s wrestling coach Mike Kiley said. “When he would walk into the gym, students would flock to him. He was just that type of kid. You wanted to be around him.”

In lacrosse, Jared’s ability to win face-offs and fly up the field untouched for goals had him dreaming of playing at Johns Hopkins.

He also excelled in his one season of football his freshman year, but the sport wasn’t for him. Football’s demands made it hard to paddle out later in the day to surf. Despite prodding from coaches, Jared called it quits after one season.

Surfing wasn’t a team sport in the traditional sense, but Jared found community along the beach with friends, surfers from neighboring schools, local riders, and even small business owners who, like most people he encountered, adored him. Surfing offered Jared something football, wrestling, and lacrosse never could.

“Surfing was no competition, no coaches, just him and the ocean,” Laura said. “He was free.”

“Mom, I don’t feel so good.”

Heading into his sophomore lacrosse season, Jared was eager to build off the success of the previous year. He was starting at midfielder for the Mustangs.

With three minutes left in a preseason scrimmage on March 14, 2019, Laura momentarily turned away from watching the game when she heard that Jared had collided with a teammate.

Jared collided face-first with a teammate and was sent to the ground. He came off the field, where Laura went to check in on him. Jared waved her off, assuring her he was fine.

Once the game was over, a still-helmeted Jared told Laura he was going with his friends to IHOP instead of coming home for dinner. About an hour later, Jared came home and walked up behind her in the kitchen.

“Mom, I don’t feel so good.”

Laura turned around to see Jared for the first time without his helmet on. There was a gash on the left side of his face. He said his head was pounding and his body felt tingly and almost numb. Without hesitation, she took him to the hospital.

ER doctors diagnosed Jared with a concussion. They told him to lay low; no screens for a few days, no exercise.

Laura watched Jared sleep the night they returned from the hospital. Doctors reassured her he would be fine, but she wasn’t one to take chances.

For the first three days after his concussion, a splitting headache and extreme sensitivity to light kept Jared from leaving his room. Laura delivered food to him and blacked out his windows to keep the light out.

Eight days after his concussion, Jared said the kitchen light bulb was “bright like the sun.”

Eventually, Jared could move around the house if he had his sunglasses on. His doctor cleared him to return to school. Lacrosse was temporarily off the table, but Laura took him to practice so he could watch his team through sunglass lenses. She demanded his coaches not let him do anything physical. They obliged.

“No, mom. I’m fine.”

Two weeks after the concussion, Jared went back to the doctor. He went through a battery of tests on his memory, vision, and balance. During the balance test, Laura saw the normally sturdy Jared struggle to maintain his balance on one foot. Still, the physician said Jared passed the test.

“What do you mean? He looks shaky. He usually balances a lot better than that,” Laura said.

Jared’s doctor reassured Laura and Jared his balance was satisfactory. He was ready to seek full clearance from the athletic trainer who went ahead and cleared him to fully participate in practice. He was set to play in Brick Memorial’s next game.

Jared was back in action, but Laura didn’t stop checking on him. After every practice she asked if he was feeling alright and if he had a headache. Each time she received the same response.

“No, mom. I’m fine.”

In the next few games after returning to play, Laura noticed a change in his playing style.

Jared normally received the ball and made a beeline to the goal to take a shot. The trademark speed was still there but gone was his usual aggressiveness. Jared was routinely passing up wide open shots to send teammates the ball.

“I’m just playing relaxed, mom. I’m just having fun,” he assured her.

Laura noticed Jared was frequently picking at the left side of his bristly head of hair. She called him on it, but Jared brushed that off too. His hair was knotted. Laura’s questions were also beginning to receive an uncharacteristic shortness from Jared.

Jared got rides to school from friends. He was usually ready to go in the mornings and waiting on them to arrive. Now, Laura had to get Jared out of bed because his friends were waiting on him.

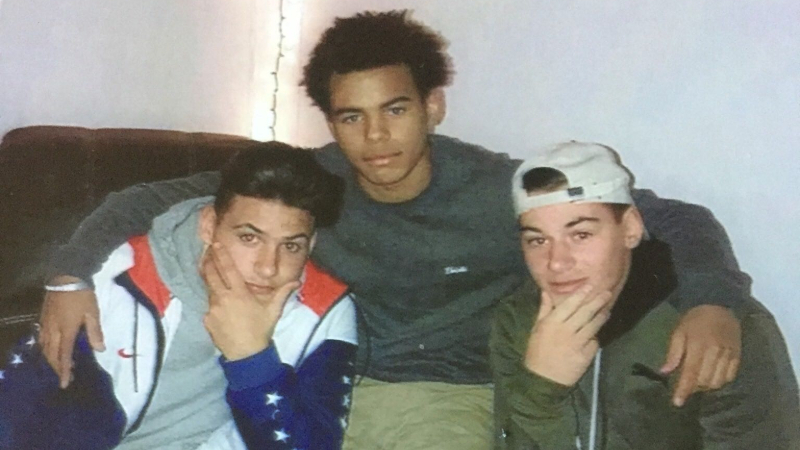

Jared with Joey Zalinski (left) and Anthony Albanese (right). Zalinski and Albanese later switched their soccer and football numbers, respectively, to Jared’s number 7.

That April, Laura found her antacid tablet container in Jared’s room. Jared said he overdid it at Buffalo Wild Wings.

Later that week, Laura had to pick Jared up from school because of his upset stomach. Again, he said the wings were the culprit.

The change in playing style, the attitude, the sleeping in, the hair picking, and the stomach issues were all peculiar for Jared but not peculiar for a typical teenager. Laura was slightly concerned about the changes, but they all had reasonable explanations. Teenagers get tired. Teenagers have attitude. Teenagers are about the only people who would eat the ghost pepper wings at Buffalo Wild Wings.

Normal teenage stuff, she thought.

On April 22, 2019, Jared came home and sat on the couch with a burrito in-hand.

He laid next to Laura to debrief about his day. He had completed his first Driver’s Ed drive with James Brite, who was also one of his lacrosse coaches. It went great. He was set to get his learner’s permit the next day. He talked with Coach Brite about next season. He sent texts to teammates about the pasta party Laura would be hosting next week before the big game against rival Brick Township.

He left for a party and returned home later that night to say goodnight to Laura and embrace her for the last time.

“I can still feel that hug,” she said.

On April 23, 2019, Laura woke up to find Jared wasn’t in his room. She called Jared’s best friend Anthony, who like all of Jared’s friends, called Laura “mom.”

“I don’t know where he is, mom.”

Laura jumped in her car and drove around town to look for Jared. He wasn’t at the gym. He wasn’t at the lacrosse fields. He wasn’t surfing.

Frantic, Laura drove home to try and collect herself. On her way, she saw a police car pulled over on the side of the street. She begged the officer to help her find Jared.

He told her to hold on a minute. Almost immediately detectives pulled up. Her heart sunk when the detectives approached her.

“Jared’s gone,” one of them said.

Jared Crippen took his own life. He left a note, written in his signature cursive handwriting. He was 16 years old.

Jared’s wake was on April 27, 2019. More than 1,500 people came to pay their respects.

Laura received a letter in the mail a week after Jared’s death from a mother of one of his classmates. She explained how her daughter suffered from anxiety and didn’t have many friends at school, but she sat next to Jared in a class. Whenever she walked into class, Jared took his headphones out, smiled, and spoke to her like few others at school would.

In the grief-filled weeks to come, friends and family came to console Laura and the rest of Jared’s family. More sympathy. More love for Jared. Still no answers.

“Jared? Not Jared. Why would he do something like that? He was so happy.”

But one night, a family member asked Laura: “Didn’t Jared have a concussion not too long ago?”

“Yeah. Why?” Laura replied.

“You better look into that. Because it could have something to do with what he did.”

So, Laura looked into it. Her research started a cascade of information-gathering. She learned more about concussion symptoms than she was ever told from any doctor or athletic trainer.

She learned after concussion, an athlete should be slowly reintegrated into their sport rather than going from zero to full-participation like Jared did. She learned about Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) and the potential for concussion symptoms to last longer than two weeks. She learned about the depth of emotional symptoms, including depression and anxiety, that can accompany concussion.

Her research led her to connect Jared’s string of odd behavior in the last month of his life to his concussion. Her instinct about the wobble in the doctor’s office. The upset stomach. The short fuse. Even the hair-picking could have been an attempt to relieve pressure in his head.

And those were just the signs she knew about.

In the weeks following Jared’s death, his friends were mainstays at Laura’s house. They ate meals there and shared stories about Jared. They laughed, cried, and told Laura other ways Jared was struggling.

She learned Jared skipped a second period, but not to get into any trouble. He skipped class to sleep in a friend’s car.

She learned Jared started drinking at parties a couple of weeks before his death. Friends say he left multiple parties because he would get upset and start crying for no reason and want to leave. Once, he and his girlfriend were at a party for just 10 minutes before leaving because Jared’s head hurt so badly.

Jared was usually the life of the party. At the party the night before his death, he sat quietly with earbuds in. Friends saw him with tears in his eyes before he left.

According to a 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the rate of suicide is twice as high for individuals who have experienced a traumatic brain injury.

Suicide is a complex public health issue, involving many different factors. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide most often occurs when stressors exceed current coping abilities of someone suffering from a mental health condition. The hopeless tone of Jared’s note began to make more sense.

Laura believes Jared never fully healed from his concussion. When he took his life, Jared wasn’t the happy and carefree kid he had always been.

“These are all the things I found out after my son was gone,” Laura said. “If I would have known these things, my son would still here. I would have immediately gotten help.”

Laura sought community to cope with her loss. She soon found out she wasn’t alone.

She spoke with Graham and Cathy Thomas, whose son Zander took his life following a concussion in 2013. She learned about Austin Trenum, who died by suicide in 2010 at age 17.

“My 16-year-old son Jared took his life 5 weeks after a concussion. I don’t know how to put my story into words… yet I have so much to say,” Laura said in a message to CLF.

CLF connected her to Gil and Michele Trenum, Austin’s parents. Talks with the Thomas and Trenum families have given Laura comfort and support. They can empathize with the inescapable guilt Laura feels and they can also remind Laura about the role a concussion likely played in Jared’s story.

“There are people out there to help you get through this,” Laura said.

“I wouldn’t wish this on anyone else.”

In the face of tragedy, Laura hopes Jared’s story can affect change. She has simple messages for parents and athletes. Messages that could have saved Jared’s life.

For athletes: it’s never worth it to play through a concussion or shake off your symptoms. Don’t play with your health, and don’t risk your friends’ health either. If a teammate is acting out of character after a concussion, as Jared was, let an adult know.

“It’s not going to help you get back in the game. If you’re not feeling well, it’s going to make it worse. You’re not going to perform like you should,” Laura said. “Wait until you’re ready, until you’re okay to go back in, because this is your life.”

For parents, Laura learned three key lessons. The first is concussion needs to be taken seriously. The second is to seek out a concussion clinic to find a specialist for your child’s concussion management. And lastly, any abnormal behavior after a concussion should be taken seriously.

“I want my son here. I could care less about how long he was out from his sport,” Laura said. “He needed to get well. I know he wouldn’t be happy, but you know what? It’s his life. And I didn’t know it was his life. Now, I know it was his life.”

She hopes athletes, parents, teammates, coaches, teachers, and everyone around a young athlete knows the role they should play in concussion management.

“It takes a village. Everybody has to watch that kid.”

“Jared was out there with us today.”

In late June 2019, family and friends congregated to celebrate Jared’s life with a Paddle Out in Manasquan, New Jersey. Christian Surfers of Manasquan organized the Paddle Out, which is a high honor in surfing culture, reserved for respected members of the surfing community.

The wake in April was full of heartache and confusion. The Paddle Out was a celebration.

Rob Brown, a coach and teacher of Jared’s, spoke at the Paddle Out. So did Anthony Albanese, the friend Laura called the morning of Jared’s death. Anthony later switched his football number to Jared’s #7. People wrote notes about Jared on seashells before sending them into the water. The group of Jared’s friends and other surfers paddled out to the ocean with flowers on their boards. Riders formed a circle, they prayed, and some of Jared’s ashes were spread into the ocean.

“Jared loves everyone who is here today,” Laura said as she closed the day’s festivities. “I need you all to know that if you ever have a concussion or you’re feeling anxious or sad or anything, you have to go to a parent or a coach. They can get you the help you need.”

When riders paddled out that day with flowers and ashes, the Manasquan waters were flat. Then, almost right after Jared’s ashes were poured into the water, waves started crashing. One surfer approached Laura and said what everyone else was thinking.

“I just want you to know Jared was out there with us today.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Walter Haney

Jack Hatton

James McLaughlin

Ethan Ogata

Ethan was born on September 16, 1994, in Honolulu, Hawaii. Growing up, he was a typical boy with lots of energy, a twinkle in his eyes, and a smile on his face. He brought his parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents so much joy!

Ethan was an avid reader and enjoyed making elaborate buildings out of blocks. His favorite activities included taking trips to the zoo and aquarium, and building sandcastles on the beach with his dad and his brother, Jacob. He was also a tremendous big brother to his sister, Kaitlin.

As a child, Ethan participated in soccer, baseball, and swimming, but never really found his passion until his freshman year at Mililani High School. There, he was part of the judo team from 2009-2012 and received the Most Improved Male Award his first year. He had never played the sport before but took a liking to it and put in the time to improve.

Judo was especially important to Ethan as it made him feel part of a team. Prior to his last season, he trained with Taylor Takata at Hawaii Judo Academy in Aiea and earned a chance to play for the state title at the HHSAA Judo Championships.

Though he fell short and placed second in his weight class, he was proud of this accomplishment considering he started with barely any experience yet found himself in a position to win it all. And in 2012, he received a silver medal at the National Judo Championships held in Irving, Texas.

Throughout his four years of participating in numerous tournaments, Ethan sustained over 15 concussions. Most were never mentioned to his family or coaches, as this would prohibit him from competing. We remember several occasions taking him to the emergency room during practice and at a few tournaments.

After graduating from high school, Ethan enrolled in community college for a year, then transferred to the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He also had the privilege to attend Queens College in New York City for a semester, as part of the Student Exchange Program. In Queens he met many lifelong friends, while exploring the city and expanding his horizons.

Upon his return, Ethan continued his studies and eventually graduated with a BA in psychology in 2021. He later took a job as a case manager at the Institute of Human Services where he helped people who were experiencing life challenges, something he could relate to and empathize with.

Ethan was very health conscious and always read food labels, especially if there was any meat or fish products, since his grandparents were vegetarian. He loved poke but tried sticking to salmon because of the higher mercury content in predatory fish. Ethan was also deeply knowledgeable about general trivia. Along with reading, his idea of fun was watching the History Channel, anything about aliens, and all kinds of different sports.

Ethan experienced life to the fullest, traveling often to countries including Mexico, Canada, Russia, Japan, South Korea, and many states throughout the U.S. As a child, he enjoyed visiting Gettysburg and got to reenact Pickett’s Charge with his dad and brother, while his mother and sister met them at Cemetery Ridge. They participated in an overnight stay on the U.S.S. Missouri on December 6, and woke up early on December 7 to imagine what the morning would have been like for the sailors on board the U.S.S. Arizona that fateful day.

On his travels, Ethan would always purchase several magnets for himself and as gifts. He also loved collecting mini snow globes from around the world, as well as any blue colored bottles he found because he knew his grandmother loved them. One experience Ethan was particularly fond of was skydiving with his good friend, Jordan, saying he “felt like he was on top of the world.”

Ethan was always thinking about ways to better his life. He was highly creative and had many big dreams for the future. Prior to his death, he was working on a business plan and market analysis for a meal prep and delivery service he created, called Aloha Express Meals. Another dream he had was to live on a sustainable farm.

Ethan was a Christian and was not afraid to die when that time would come, because he knew he would be going to heaven to be with Jesus. We are so happy that in sixth grade at Vacation Bible School, he accepted Jesus Christ into his heart as his personal Savior.

Life threw several challenges at Ethan, which he overcame to be a stronger and more resourceful individual. Along with sustaining several concussions while training for judo, he also survived a major head-on car collision in 2016 while at a drug treatment center in San Francisco. The car did not have airbags and his head cracked the windshield. After that, Ethan was never the same.

He complained of extreme headaches, pain, cognition and balance issues, had problems with memory loss, and could no longer perform simple, everyday tasks. While seeking medical attention at a pain management clinic, he was given opioids to ease his pain and suffering.

Throughout the following years he tried his best to get psychiatric help and sought therapy. We noticed many behavioral changes, which Ethan was aware of as well. He suspected his symptoms were early signs of CTE and verbalized his thoughts to his family on several occasions.

Though Ethan continued to see his psychiatrist on a regular basis, he felt he needed more help and entered drug treatment a third time. He wanted to stop having to rely on all the various medications he had been prescribed. Unfortunately, on the evening of December 11, 2023, he was found unresponsive. Ethan was only 29 years old. His cause of death was an accidental overdose on opioids.

After speaking with the Honolulu Medical Examiner’s office and with his history of concussions, the decision was made to have his brain examined for possible CTE. On May 29, 2024, we received the written report from UNITE Brain Bank researchers that there was no evidence of CTE. However, they did find white matter throughout the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortex, which is commonly seen in those with a history of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).

Ethan is survived by his parents Garret and Michelle, brother Jacob, sister Kaitlin, paternal grandparents Masayoshi and Frances Ogata, maternal grandmother Toshiko Foss, and his cat Charlie, who misses him dearly. He is predeceased by Ronald G. Foss (2019). We all miss his smile, his unique sense of humor, his generosity, and willingness to help his family and friends.

With the assistance of the UNITE Brain Bank, we were introduced to the Concussion Legacy Foundation. We are very grateful for the opportunity to share Ethan’s Legacy Story to raise awareness of what concussions and TBIs can do to an individual.