Mark Cunard

Randy Davis

Steven Dudowitz

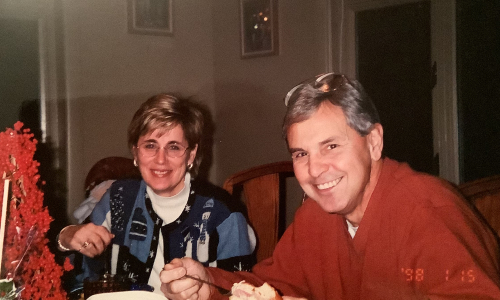

Jim Proebstle, author of Unintended Impact, sat down with the family of Steven Dudowitz to gain insight into his life and legacy.

Steven Dudowitz: A Tragic Story

The story begins

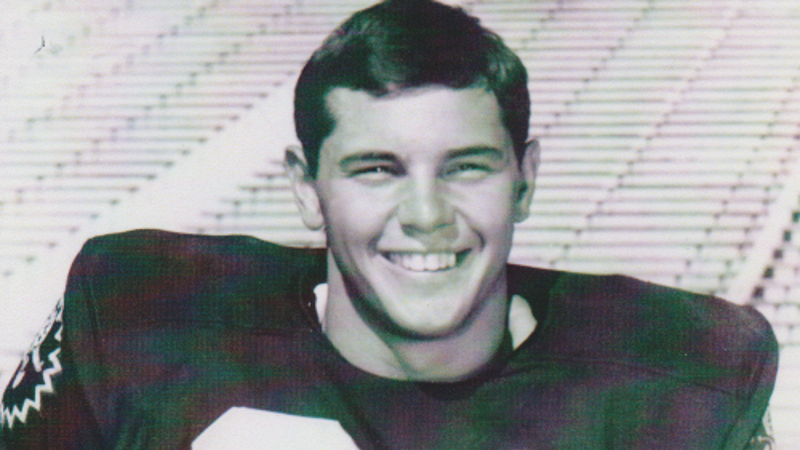

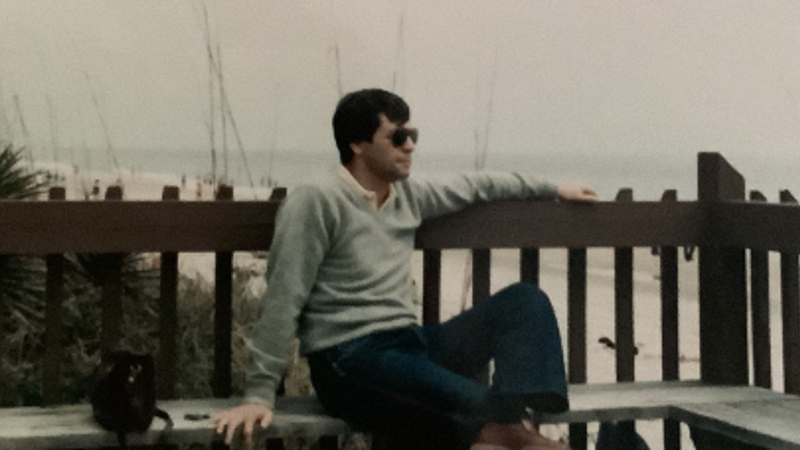

As an outstanding offensive tackle for Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, NY, considered to be the perennial favorite football program in New York City, Steve’s journey is different. After graduating, “the Dude” as he was called, continued playing at Geneva College (formerly Beaver College) in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. At 6 foot 1 inch and 200 pounds, Steve was not your stereotypical offensive tackle and was put on the coach’s watch list for players who were too thin. He worked his way up to the second string, only to develop knee problems, which was his undoing for playing football his sophomore year. According to Boston University’s School of Medicine Clinical Report, Steve experienced six concussions, but no one really kept track of how many times you got your bell rung back then. With today’s knowledge of the damage incurred by repetitive nonconcussive blows to the head and the lack of sideline safety protocols for concussions in the 70’s, it’s hard to estimate the extent of impairment done to the brain.

A successful career interrupted

Steve developed a thriving career in the securities industry starting in 1979 in a classic style. He started in the mailroom. For the next 37 years Steve continued to assume additional responsibilities through job promotions, company changes and various mergers. The dedication and compassion he showed to those who worked for him was unparalleled. Yet, the fairy tale story wasn’t quite what it appeared to be. Control issues presented themselves. An under the radar substance abuse and alcohol issue contributed to a substantial weight gain to over 300 pounds. The corporate move in 1999 to Switzerland was partly designed for him to get back on track, as he seemed lost and unfocused by those who knew him best. In parallel, his first marriage came to an end.

In 2001, he met Juliette. They bought a house in 2003, had their only daughter, Stephanie, in 2004 and made it official by getting married in 2009. Along with Alexia, Juliette’s daughter from a previous marriage, they began a new life—no drugs, no alcohol—yet the job stresses continued to mount. His personality started to unravel, moments of extreme irritation and anger boiled over as an apparent loss of control led to OCD mannerisms in the strangest of circumstances. Erratic behaviors continued to worsen over time with noticeable memory issues in his mid-fifties. Steve closed down and began spending hours on end in his man-cave, by himself. His participation in the marriage was stunted and initial requests to see a psychologist were categorically rejected. Everything bothered him.

Mysterious changes

In October, 2014, it seemed as if Steve’s brain just flipped. Maybe the new company merger had an impact, but judgement and fault-finding became a normal part of many discussions, almost always over trivial events. Memory issues increased. Lifelong friends were dropped for no apparent reason. Juliette was struggling to understand what was happening with Steve with the sudden increase in financial challenges, credit card irregularities, spending splurges, strange disinhibitive behaviors, depression, anxiety, divorce threats, impulsivity, and explosive rages. Everything was coming at Juliette rapid fire with no reasonable explanation—the wheels were off. He was becoming more difficult to deal with as their lives took different paths. Juliette made up her mind to stick by Steve but he was no longer himself and she just didn’t know what to do. He was making comments about being in a bad place, about not knowing what’s wrong and, in general, about feeling strange and different. It was at this time that he agreed to finally go to seek therapy. Maybe he wasn’t having a mid-life crisis. Maybe he was sick.

It was during the movie, Concussion, with Steve and their daughters, Stephanie and Alexia, that Juliette made the connection with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and Steve’s quickly devolving circumstances. Steve responded by looking at Juliette as if she were crazy..

Taupoathy: Closure… maybe

Steven had his heart attack on 5/12/16 and died on 6/13/16 while in hospice care. Juliette decided to contact Patrick Kiernan at Boston University School of Medicine CTE Center in order to donate Steve’s brain for research. The family received a different diagnosis from what they expected, however. The Clinical Report identified a neurodegenerative diagnosis called tauopathy. Related to CTE, tauopathy is somewhat different based on the unique deposition of neurofibrillary tangles. The unique findings in Steve’s brain opens a new door for future research as other cases are discovered. It would appear that the destructive path of concussions is not limited to a single answer (CTE) that could be made into a movie. The family is entering a new and frustrating world in search of more answers to connect the dots between Steven’s life and his untimely death.

Copyright © 2017, James Proebstle

Troy Ellis

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Troy Ellis had a big presence and an infectious personality. He was very handsome and charismatic. The boy could dance too, and he was the life of the party. He was often told how much he looked like Channing Tatum. Troy thought he could play Channing’s younger brother in a movie. He would say, “If I was given a dollar for every time someone told me I looked like Channing, I’d be a millionaire.” He was fun, energetic, lovable, and loved by many. He recited lines from movies on a regular basis, especially from the movie Forrest Gump, which always produced lots of laughs.

Troy Boy was a natural athlete, showing his abilities very early on in his life. He couldn’t even walk yet but was always reaching for a ball of some sort. When he was two years old, he received a baseball and glove as gifts. He slept with them and called it his “glub.” His older sister, Lauren, was also very athletic. I knew, as well as their father, that we were going to spend a great deal of our lives watching them play sports. They were talented and eager to compete. They made each other better and there were fights along the way. Both were voted “Most Athletic” by their peers in high school. His sister was his hero. Troy was Lauren’s best person and stood up for her when she was married.

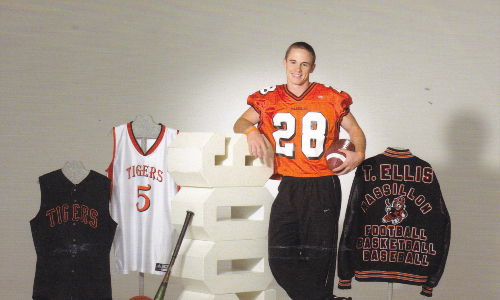

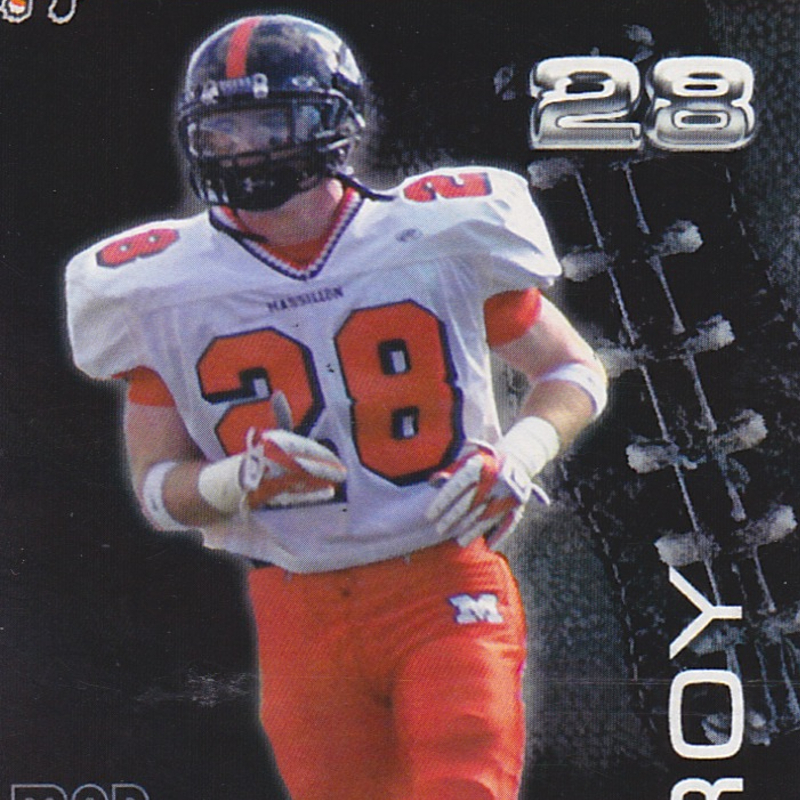

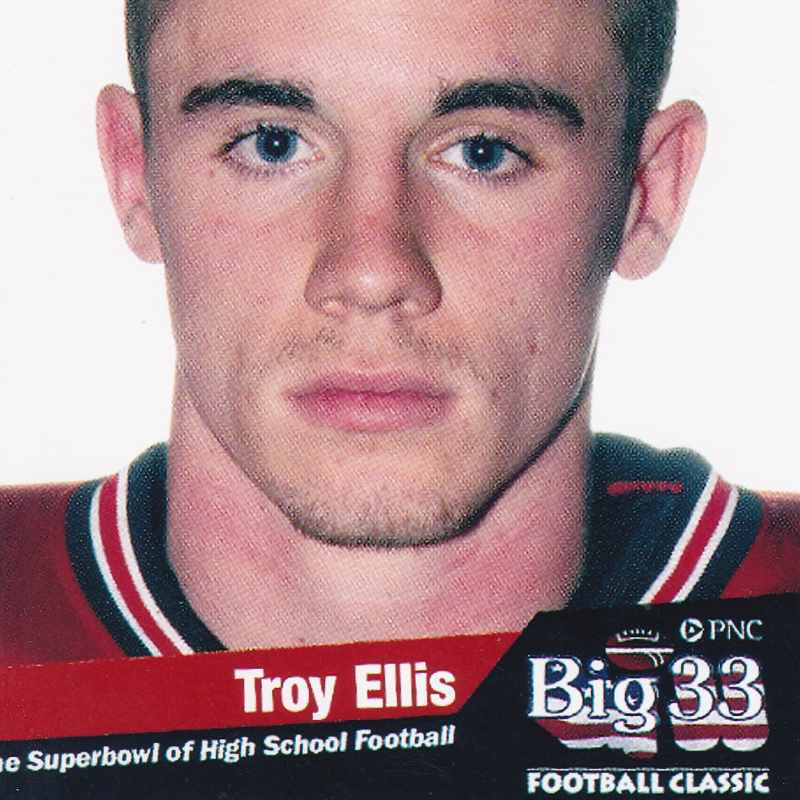

Troy played soccer, basketball, baseball, and of course, football, which he started in the fifth grade. He played for the storied Massillon Tigers in Massillon, Ohio. Football is close to godliness in Massillon. Troy loved the game. You are somebody when you are a Massillon Tiger. Little kids looked up to him and wanted his autograph. He was a three-year starter and never missed a game, playing cornerback, wide receiver, and punt returner. He was second team All-Ohio his senior year and was on the All-Stark County Team. He played in the Big 33 game in Hershey, Pennsylvania in 2006. He was a one-man highlight reel his senior year against Cincinnati Elder at the Cincinnati Bengals stadium. He had five interceptions in this one game (a record for the Massillon Tigers) while also recovering a fumble and returning it for a touchdown. He was named the game’s MVP.

Troy was known as a hard hitter and received the Bob Cummings Hardnose Award his senior year as voted on by members of the Massillon Tiger Booster Club. Former NFL player Chris Spielman also won the same award in the past. Troy received many accolades in the sports he played and he earned them all.

As his mother, I always thought baseball was Troy’s best sport. He was a four-year varsity starter in high school, the first at Massillon since 1975. He played second base and then shortstop. He played for the Stark County Stars in summer ball. A local reporter said, “Troy is the epitome of a leadoff hitter.” He went on to play shortstop at a junior college, Olney Central College in Illinois, for two years. While at Olney, he played a game at Busch Stadium. He also played Class A ball in Kentucky and played for the Canton Terriers.

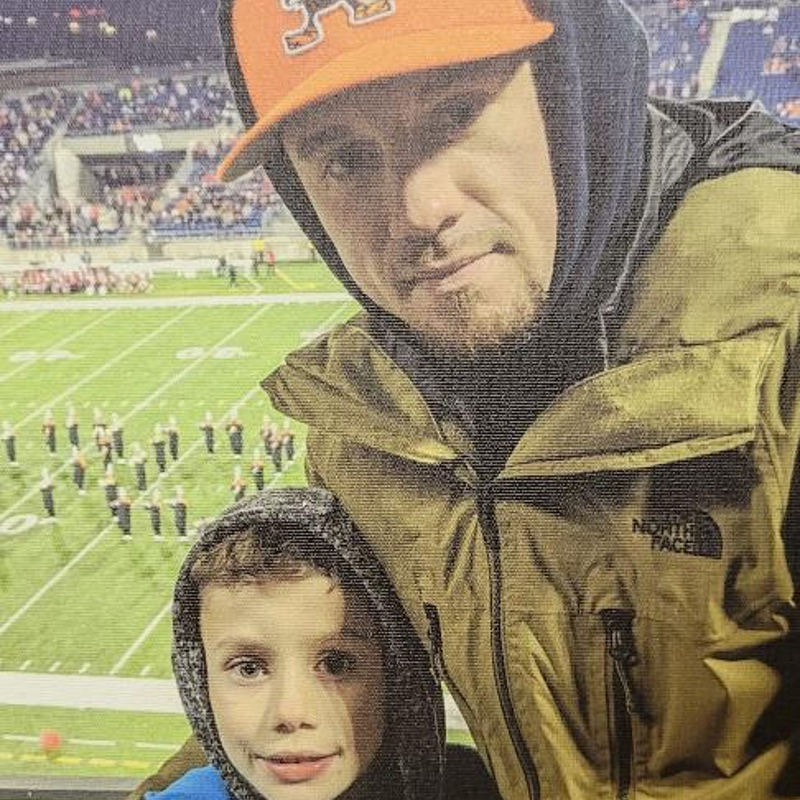

Troy had a son, Ashton, who was 10 at the time of Troy’s death. Troy and Ashton’s mother were no longer together, but he would get Ashton nearly every weekend. He enjoyed teaching him about baseball, football, and basketball. He installed a basketball hoop in his basement for Ashton. They would go fishing, golfing, roller skating, and played laser tag. He also shared his love of music and dancing with his son. Several years ago, Troy bought Ashton a pair of LeBron’s shoes in a large size that he has yet to grow into.

Troy was employed as a third generation plumber and pipefitter out of Local 94 in Canton, Ohio. His coworkers loved working with him. He also helped coach a middle school girls’ basketball team and was often known to lend a helping hand to others.

Troy had multiple head traumas from a young age. He fell out of a wagon and hit the back of his head on the cement floor. He fell off the side of the basement steps. He rode his bike down the deck steps. The front wheel came off of his bike and he fell face first into the sidewalk. The worst head injury was when he fell out of a tree at age eight and had a brain bleed. That was the worst day of my life, until the day he died. He was in the ICU for three days and in the hospital for a week. In time, he recovered and was cleared to continue playing sports. Additionally, he took a nasty pitch to the left side of his face while playing college baseball.

I would say around 2014 is when we started noticing changes in Troy’s behavior. He was very forgetful, erratic, angry, and engaged in risky and impulsive behavior. He started to struggle with life in general, including with money and getting in trouble with the law. He had relationship issues with family members, friends, and with women. In hindsight, I don’t think he was capable of settling down due to the CTE. I was so worried about him all the time. By 2020, the only thing predictable about Troy was his unpredictability.

In the early morning hours of December 26, 2021, Troy was believed to be the person who started a fire at his girlfriend’s home. The house was destroyed but fortunately no one was home at the time. Several hours later I received a call to go check on him. I did and he was distraught like I had never seen him before. He would not let me in the house. Shortly thereafter, he shot himself in the chest. As he was being loaded into the ambulance, he told me he was sorry. I could not see where he had been wounded but asked him if he was OK. He said, “I’m gone.” He told the paramedic to tell me he was sorry, that he loved me and this wasn’t my fault. He made the paramedic promise to tell me. Troy died three hours later. We did not get a chance to see or talk to him again.

The Massillon Tiger Community honored him after his death. Bracelets were made and sold with his football number on them and engraved “#28 Forever T.E.” Baseball hats were made with his number, as well as jerseys with a picture of Troy on the inside of the back of the neck. This way, Troy could “have their back.” Family members started a crowdfunding and all of the funds are being held for his son. The person at the mall who made the hats said, “We have made so many of these hats in memory of Troy Ellis. He must have been someone very special.”

I need to emphasize that I am not attempting to glorify Massillon Tiger football. I’m simply telling a true story about my son and his history of being a Tiger. Massillon football fans tend to over glorify their players. The kids are put on a pedestal and it’s just too much at times. The players in this program are more revered than those at most college programs. Many players have gone on to college and it has been a big letdown for them. I look at football through a totally different lens now.

After Troy’s death, his brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 1 (of 4) CTE. Had I known more about CTE, I would never have allowed him to play football. I have learned so much more about CTE and the devastating consequences it brings. I would never advise anyone to play football, or any sport suspected of causing CTE. His glory days turned into his gory days because of CTE. Simply put, the glory days were not worth it. I strongly urge parents to do their own research into CTE and make wise choices for their children, including supporting CLF’s Stop Hitting Kids in the Head. I certainly wish that I had. It’s too late for me now.

Troy said to me, later in life, “Football is a violent game, played by violent men.” After he passed, we were told that Troy had shared with others that he had “demons in his head and he was scared for himself.” He also said there was something wrong between his ears. He never shared that information with us.

We are all devastated and continue to carry a heavy load of grief, and the guilt that comes along when a loved one takes their own life. We love and miss him constantly.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Andrew Erker

The morning of January 11, 2017 started out just like any other morning. Andrew got out of bed early to send me off to work with a big hug, kiss, an “I love you” and his typical, “Whatever you do today, just be a good person.”

Andrew’s number one priority in life was to be a good person regardless of the circumstance. He never failed to live up to that standard he set for himself. I would always receive a text late morning just to check in and see how my day was going. Not hearing from him at all that day in January made me a little uneasy. Driving home from work that night I knew in my gut something was very wrong. Andrew died by suicide earlier that day in our home.

This horrific tragedy came as a massive shock. Surely that wasn’t him. It didn’t make sense. Andrew had such a love for family, his friends and me. His enthusiasm for life, nature and wildlife was unmatched. He would light up a room with his smile. Andrew was the most selfless man I had ever known. His intentions to make everyone happy and be a better version of themselves were as pure as they come.

Something in his brain was not right that day and hadn’t been for a long time. Andrew was not the type to complain or ask for help. He refused to burden or worry anyone. He wanted to do it all himself and was determined to do so. I believe he suffered internally for longer than I knew or could ever imagine. Andrew’s sense of humor was one of his best qualities. He was constantly making everyone around him smile and laugh. For as long as I knew him he would joke about football messing up his brain. He believed it made him “stupid” even though he was thriving at work and nothing about his daily life made it seem like he was missing a beat. Joking about it I believe was his way of trying to tell me something wasn’t quite right without making me worry. When Andrew and I started talking about having a family his number one rule was that our kids would not play football. It was becoming clear to me that he was truly worried about the toll football took on his brain.

Andrew and I met at a bar in Kansas City in 2014. I was 22, still in nursing school and he was 27 living in Lincoln, Nebraska. He was home for a weekend and out with friends when we met. From the moment I met him I knew he was incredibly special and early on we both knew it was meant to be. He moved back to Kansas City the following year and we were married in April of 2016. Nine months later he was gone.

Andrew played tackle football from the time he was a child through his college career at Kansas State University, where he played safety. Andrew was not the biggest player on the field, but he was tough and known for his hard hits. I believe Andrew suffered several undiagnosed concussions during his time playing football. He told me about several games he didn’t remember after playing in them and times where he just didn’t feel quite right after games.

A few months before he died, I started noticing the forgetfulness. He couldn’t recall certain conversations or plans we made. Towards the very end of his life he became more irritable and his patience was diminishing. Although his anger seemed to be heightened in the last couple weeks of his life, I do feel as though his emotions were fairly well controlled. It seemed as though Andrew was somehow able to mask many of the typical signs and symptoms of CTE.

Andrew’s family and I decided right away to donate his brain based on his football history and his recent behavior. Andrew was always helping others so when donation became an option I knew he would jump at the chance to try and help save someone else’s life. Boston University was an obvious choice for us, and I could not be more grateful for how we were treated and supported during this incredibly difficult time. I felt as though Andrew was respected and appreciated by the researchers from the UNITE Brain Bank from day one. Seven months after he died, Andrew was diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE. We were all shocked to see such advanced disease in a 30-year-old.

I want people reading Andrew’s story to understand the dangers and possible effects playing tackle football as a young child can have on your brain and your life. I want people to know that CTE can happen to anyone with a history of repeated head impacts like Andrew had. Choosing to put your child in tackle football at a young age could end up destroying their life and leaving their loved ones completely devastated. I know Andrew would have much rather sacrificed his football career for his life than his life for his football career.

I feel incredibly lucky to have fallen in love with a man who I know fought like hell against an uncontrollable brain disease to protect his friends and family.

__________________________________________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Larry Facchine

Larry Facchine grew up as an outstanding athlete, excelling in every sport he participated in – basketball, baseball, golf, tennis, and primarily, football. He was raised in Vandergrift, Pennsylvania, your typical small western Pennsylvania town where, like in the majority of Pennsylvania towns, everyone looked forward to Friday night high school football. There could have been no better place for Larry to spend his school years. His last four years of high school found him on the football field every Friday night doing what he loved.

After graduating from high school, he accepted a scholarship to play for Arizona State University. He loved ASU and he loved playing for the Sun Devils. He played both quarterback on offense and safety on defense and was a three-year letterman. He played hard and got hit hard. During one game, he was hit so hard his helmet broke. His senior year in 1963-64 was an exceptional year. The team had an undefeated season and he received the “Mr. Hustle Award” given for outstanding performance.

Larry and I met in the summer of 1969 when he returned to Vandergrift after coaching in Arizona. I had never met anyone who had his drive. He was tireless and relentless in his thirst for learning about everything imaginable. Nothing was ever “good enough” for Larry. He always tried to make himself or what he was doing better. I know these traits are what helped him succeed in everything he did.

I had just signed a contract for my first year of teaching and Larry had taken a teaching and assistant coaching position at the Jeannette School District nearby. He worked with an incredible group of young players. In his third year with them, they won the Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League Championship. It was one of the proudest memories of Larry’s football career. It made him realize how coaching, mentoring, encouraging others, and watching them succeed were what gave him the most satisfaction. After that third year, Larry accepted a head coach and athletic director position in another district, but he took with him a special, life-lasting bond he had fostered with so many of the players.

In the years that followed, along with coaching football, he gave golf and tennis instructions to youths and adults, became an emergency medical technician, taught golf at a community college, and began practicing intently to qualify for the senior golf tour in the future.

About seven years after he left Jeannette, his former quarterback stopped at the house for a visit. He was working for a water treatment company and had his boss with him. He had told his boss that Larry would be a perfect representative for the company because of his drive and personality. And that was the beginning of his career in the water treatment business. After working with the company for nine years, he decided to begin his own company and did so very successfully. And still he continued with giving golf and tennis lessons, coaching Little League, and practicing his golf to achieve his goal of joining the senior golf tour in the future. He never stopped touching lives and encouraging those he mentored.

Many years later, in 2011, Larry noticed he began “losing” words. He would know what he wanted to say but couldn’t retrieve the words. He thought it might be the beginning of Alzheimer’s Disease, so he met with doctors who put him through extensive intellectual and medical testing. It was determined he didn’t have the beginning of Alzheimer’s but did have blockage of the blood flow to the left side of the brain due to head trauma. Since this area of the brain was the language center of the brain it explained the occurring language problem.

Larry had great respect and confidence for our family doctor. We kept him informed about the Alzheimer’s study, the language problem, and all his developing mental and behavioral changes. It was our doctor who first mentioned the possibility of CTE. That was quite a surprise because it had been 46 years since Larry had been on the football field. As time went on, Larry started suffering periods of depression, thoughts of suicide, and unexplainable bouts of anger. Not only did he have trouble communicating but he had difficulty processing what was being said to him. Because Larry would only see our family physician, our doctor consulted with his neurology staff for possible medications that might help the changes being experienced. When medications were not helping and Larry’s condition was worsening, our doctor suggested a hospital stay to try to get a regiment of medication that might help manage the ever-changing conditions Larry was experiencing.

Larry spent 11 weeks in the hospital and finally came home with a treatment that worked. The treatment didn’t eliminate his problems but helped with them. Unfortunately, this treatment also created other new problems and took so much more away from him. He had to get used to a now unfamiliar home and no longer knew our friends and relatives.

Conditions for him worsened and after six months at home I realized I could no longer give him the care he needed because of the ever-changing behaviors. After searching for and visiting many facilities, I finally found Newhaven Court Memory Care which proved to be his home for the next two years beginning in January 2018. It was heartbreaking to face this major change in our lives.

Surprisingly, Larry adjusted to the change better than I ever would have imagined. The director of the Center took a personal interest in CTE when I told her that might be what we were dealing with. She researched CTE and learned as much about it as she could. She trained her staff to provide phenomenal care for Larry. At this time, he no longer knew people’s names and could not carry on a conversation or answer simple questions, but he seemed more content and calm. Within a few months, because his physical abilities were diminishing so rapidly, he started receiving the care of a wonderful hospice group. I spent many hours with him every day and was awed by the love and care the group continually gave Larry. As he lost the fight against the effects of what we believed to be CTE and could no longer speak or walk or eat, I was at least at peace with knowing he had had the best possible care.

Larry passed away on December 22, 2019. He was 78 years old. His brain was then studied at the UNITE Brain Bank, and the results of the CTE Neuropathology Report from Boston University CTE Center confirmed Larry did have CTE in addition to severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Knowing this didn’t change my sadness or the unbelievable loss I felt, but at least I had a reason for all that he had suffered. CTE had taken away many healthy years that he could have had, but it didn’t take away the person he was and the lives he touched. Even now I am constantly reminded of that by visits, phone calls and letters from those he mentored. That, indeed, was his legacy.

Becoming aware of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and all the research and studies being conducted to advance public understanding of CTE gives me such hope for the future. So many strides have already been made and much more will be achieved in the future because of the determination and hard work of everyone involved in the Foundation. I am forever grateful for their assistance and support and I am proud to be a part of it in some small way on behalf of my husband.

Dennis Farrell

“Don’t take life too seriously.”

This was the last wisdom Dennis shared with his children and family.

Dennis the Menace and Iron Papa Bear were his given nicknames. These offer you a glimpse into the life of this son, brother, father, and friend. He was a kind, loving, generous, strong man with a bright smile. He was born in Miami on the third day of the third month and was the third of nine children; three was always his lucky number. His family relocated back to Illinois when Dennis was a toddler. He had many fond memories growing up — causing trouble with his five brothers and neighborhood friends. His three sisters were around to try and keep them in line.

Learning didn’t come easy for Dennis. Being one of nine children, he needed a way to stand out. Exceling at sports was his thing. His success helped to deflect bad attention from his grades. He had natural talent, and he gave it his all from a very young age. He played baseball, basketball, and football. Football was Dennis’ pride and joy, and he starred at linebacker. He played for a junior league for three years, before entering Gordon Tech High School in Chicago. There, his incredible talents on the field earned him a full football scholarship at Illinois State University. A friend said, “I saw him get his bell rung multiple times. We didn’t know what the lasting effects were; we just got back up and played.” He played three and a half years before suffering a career-ending knee injury. He changed majors and knew he wouldn’t complete his education in four years, leaving Illinois State to attend a trade school. Following in his father’s footsteps, Dennis became a devoted millwright (heavy machinery mechanic). Later in life, he coached football teams in his hometown. He loved to watch the game.

Dennis had two children. He was married to their mother for 14 years. After their divorce, he never remarried. He was a devoted father and was never considered a part-time dad. Whether it was his son’s games or practices or his daughter’s musical performances he never missed the opportunity to cheer them on.

“We were and will always be a family, even as unconventional as we were.”

Dennis loved the outdoors. He liked to sail on Lake Michigan, golf with friends and family, and go on walks/hikes. He considered himself a born-again hippie, free spirit and all. He was also a craftsman at heart. He loved creating beautiful furniture pieces, winding stairs, decks, and any remodeling projects. He often worked with his brothers to complete home renovations and projects at one another’s homes.

Dennis experienced a lot of life. He traveled to where work was available in his trade, offering him many different sceneries. He traveled yearly to Arizona to spend time with his mother. This was special considering he was one of nine. Family was important to Dennis and he spent a lot of time with his brothers and sister who lived nearby in Chicago. They would attend festivals, garden together and have the best barbecues. He relocated to Miami for several years working with the millwright union there; he loved being back in the city where he was born. When not working, he enjoyed activities on the ocean. He watched both of his children graduate from college, get married, and he was able to walk his daughter down the aisle. His son granted him the title of grandparent (known to his grandchildren as papa). He enjoyed spending time with his two grandsons and attended many of their various sports events. They brought light and joy into his life. Usually you’d see Dennis sporting a tie-dye t-shirt with a feather earring in his ear.

Other than behavioral occurrences, no one thought Dennis was being anything other than himself. All our lives our dad was different, unique, and one-of-a-kind. We learned from him to accept people for their differences, as you’ll come to appreciate them in the end. In 2012, he had a cardiac episode that led doctors to perform a triple bypass with a mitral valve replacement. It was an extensive ten-hour surgery. It took him eight days to come off the vent. Once he was off the vent and coming around, he bounced back fairly quickly. He was doing great. He visited friends, engaged in light activities he enjoyed, and kept himself busy. He did retire from being a millwright after 36 years due to his heart.

In 2015, we started to see signs that were the beginning of the end, although no one knew at the time. He was making poor choices, forgetting to pay bills, and misplacing things. Over the next three years, he stopped engaging with friends. His mobility decreased and he couldn’t participate in the activities he loved. His children stepped in to help and find out what was causing these changes. We went to ten different doctors trying to find answers. Specialists would point to another one saying it wasn’t in their realm of medicine.

Dennis’ children helped manage his finances, insurance paperwork, and care. They shared doctor appointments and kept one another updated. The last couple years of his life family pitched in to help with his care. His children’s mother took him to a couple doctor’s appointments. A sister offered guidance and support, with her knowledge of the medical field. One of his brothers visited and took him out to different places. His other siblings gave motivation through messages and phone calls. As his symptoms and ailments progressed and we read more information on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, it started to sound like it fit the best with what we were seeing. The movie “Concussion” felt all too real. Doctors had told us there was no way Dennis had dementia; it was all behavioral. Another said, “he didn’t get hit enough times to have CTE” and that they could help him gain all his independence back. Many said they had no idea why everything was declining rapidly. They tested him so many times for so many different diseases. Traveling to Boston in December of 2017 with his daughter and son-in-law for Diagnose CTE Legend Study was the first time we felt like he was understood.

His wishes were to have his brain and spine donated to the UNITE Brain Bank. He wanted to donate not to help himself but to help others in the future.

Dennis had a great cardiologist that assisted when we needed advice or direction. In August 2018, we met a neuro-muscular specialist who worked so hard to help us. She came into the picture in the last quarter of the game and found answers. In September 2018 he was diagnosed with ALS — a couple years after the first symptoms appeared. Through all the struggles Dennis never gave up and did everything they asked him to do. He did daily PT and OT, until three days before his passing. He worked so hard. He wasn’t ready to leave his family. Surrounded by his children, on October 31, 2018 (Halloween), he passed away from complications related to ALS.

Dennis passed knowing he wasn’t going to find answers. He found peace knowing that we, his family, would get answers about what he was suffering from. More important to his final wishes, he knew his donation would benefit others in the future. Researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank discovered that he had Stage III CTE with ALS. Dennis Farrell loved football. We know for sure he still would have played the game he loved, but he would have played safer.

The best advice we can offer is keep notes and make observations of your loved one. You know them best. Spend lots of time and have lots of patience. Don’t stop trying to find answers. Advocate for those who can’t fight for themselves. You will find someone and a place to help. The staffs at the Boston University CTE Center and the Concussion Legacy Foundation have been amazing. They offer guidance and advice that many of the professionals in Chicago he saw couldn’t provide. We are grateful to the whole team in Boston.

We will forever love our father and will honor him every day for the rest of our lives. We miss him but know he is in a better place. Dennis’s famous sign off: Peace, Love, & Bell-Bottoms!

Hunter Foraker

As the coroner walked through Hunter Foraker’s apartment in Dallas, Texas, on September 18, 2017, she noticed football helmets displayed on his shelf.

They called Kim Foraker, Hunter’s mother, and asked her if she was interested in having an autopsy on Hunter’s brain. In their search for answers following Hunter’s suicide, the Forakers agreed.

Four days earlier, Kim, her husband Bill, and their daughter Jordan all spoke with a jovial Hunter. He was getting a carwash. The new job was great.

“Looking back on it, we all think he was drinking and just a little happier than usual,” Jordan said.

“Perfect”

Hunter Foraker was born on May 11, 1992. Within a year, he was in skis and joining his dad Bill on the mountains of Colorado. His childhood was spent doing all kinds of outdoor activities like mountain biking, camping, hiking and fishing.

Normal kids may fib every so often. Young Hunter was steadfastly loyal and honest to his family.

He had a drive for perfection that carried over to the classroom and every field Hunter stepped onto.

Hunter was a teacher’s dream. He may not have been the very sharpest in his class, but he was quiet, humble, respectful, attentive, and determined to do his best. His competitive spirit pushed him to do more and do better than his peers.

“I always thought it was the pressure to be perfect,” Jordan said. “He would stay up studying and working for hours because things didn’t come as easy to him, but he would put in the time to understand it just the same.”

Hunter dabbled in many sports but found the most success in football. With Bill as his coach, Hunter started playing tackle football in second grade. His size, athleticism, and aggressiveness made him a natural fit at linebacker.

“It was so wonderful to see Hunter and Bill together in a sport that gave Bill so much pleasure and fulfillment as a youth and knowing that Bill was coaching Hunter in the correct methods of hitting and tackling so that Hunter would not be injured,” Kim said.

“I Remember Seeing ‘Big Green’ Everywhere”

It didn’t take long for Hunter to make a name for himself on the Mullen High School football team in Sheridan, Colorado. He made varsity his sophomore year and was named a captain the following two years.

Hunter’s senior season at Mullen in 2009 included a long list of accomplishments. He recorded 100 tackles and led a Mullen defense that allowed just 5.7 points a game in their 14-0, state championship season. Hunter was named to the 5A First Team All-State roster and the state’s All-Academic team.

“I remember his senior year we went to some fancy dinner as a family, little did I know it was because Hunter was nominated for a pretty big award,” Jordan said. “Hunter acted like it was just another banquet. He was so humble.”

Football was a means to an end for Hunter. He decided before his junior year of high school that he wanted to attend an Ivy League school. He worked diligently and had great grades but knew he would struggle to get into his dream schools without football.

“He wanted to play with a higher level of player,” Kim said. “A player that wasn’t simply focused totally on football but had a future outside of football in mind.”

Dartmouth became the apple of Hunter’s eye. He loved that skiing was encouraged after the football season. He would be right at home in the cold Hanover, New Hampshire winters. He returned from his visit to campus and wrote “BIG GREEN” on everything he could at home. Later that year, he was ecstatic to learn he was accepted into Dartmouth and would play football there.

Football star. Ivy-bound. From the outside, Hunter succeeded in maintaining the image of perfection. But signs of deeper problems emerged in high school.

The confidence he played with on the gridiron was contrasted by a palpable anxiety in other parts of his life. His family believes the internal pressure he put on himself prevented him from trying new things.

In Hunter’s teenage years, massive mood swings began. Once, Bill confronted Hunter about why there was a scuff on his truck. The simple question caused Hunter to erupt and nearly strike his father.

Hunter began having terrible nightmares in high school. His dreams were so troubling he could never describe them to his family.

His junior year, Hunter intimated he wanted to end his life. After several consults, a psychiatrist told the Forakers that Hunter would be safe.

Hanover

Hunter was eager to start the nearly 2,000-mile journey from Littleton to Hanover. Once on campus, he adjusted well and quickly made new friends. He was a standout on the Dartmouth JV football team where he resumed his role as a magnet to opposing ballcarriers. Hunter’s freshman year was a success, save for a brutal biology course that dashed his pre-med dreams.

Hunter suffered a concussion in training camp prior to his sophomore season. The Forakers don’t know the details of the injury, but they know the injury left Hunter with a constant headache. Hunter had seen many teammates come back too early from concussions and wanted to avoid the issues that plagued them. He elected to retire from football. The sport had done its job and helped to set him on the path he so desired.

Once Hunter no longer needed to be a hulking linebacker, he became obsessed with his body image. He weighed himself several times a day and had strict discipline about what he ate.

After graduating with a double major in Environmental Science and Anthropology in 2014, Hunter stayed in Hanover to work for Dartmouth’s alumni relations department. He was in a place that gave him great joy over the last four years, but boredom and loneliness set in without the people who he had experienced his undergrad years with.

In February 2015, Hunter called home. He was in a rehab program for alcoholism at a Dartmouth Hitchcock hospital.

“It was surprising because he was so in control of everything,” Kim said. “He was so in control of his body.”

Tough Love

Hunter moved to Utah in August 2015 to work as an expert gearhead in Salt Lake City. There, he advised people on all the outdoorsman activities he grew up with.

He was closer to home but further from who his family had always known him to be. The Forakers sensed Hunter was intensely ashamed of his alcoholism. The boy who could not tell a lie was now lying to his parents’ faces.

He told his family he had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and was on a myriad of medications. The Forakers don’t know how much of what Hunter told them was true. They do know Hunter spent much of his two years in Utah rotating between emergency room visits, rehab facilities, and detox centers.

In January 2017, Hunter called home to let the family know he was going to Durango, Colorado for a ski trip. They began to worry when calls and texts to Hunter went unanswered later in the weekend.

Kim arranged a wellness check from local police. Police found Hunter. He had the highest blood alcohol level they had ever seen. The Forakers learned Hunter went to Durango to drink himself to death. He survived the suicide attempt and was taken to a nearby hospital.

Following the attempt, the Forakers were at a loss for how to support Hunter. They sought professional counsel and were advised to implement a strategy of tough love with their son.

“It was the most difficult thing we have every done in our life,” Kim said. “Professionals were telling us on one hand to practice tough love and to not have any contact with him. But your heart is telling you to be a loving parent and to be there unconditionally.”

Hunter turned against his family and set out on his own back in Utah. For the first six months of 2017, Hunter was in a revolving door of sobriety, rehab, and halfway homes. Later, the Forakers found out Hunter experienced eruptions during this time like what they saw in high school.

“The Old hunter Again”

In July 2017, Hunter finally contacted the family. They visited him in Salt Lake City where Hunter was in sober living. For the moment, it seemed like Hunter had tackled his demons.

Hunter came back home to Colorado for a brief stay with his family in August 2017. He was clean. He wasn’t looking for scales to weigh himself. He had a new haircut and bought new clothes. He was happy. The Forakers were thrilled.

Hunter apologized to Kim for his suicide attempt in January. He promised he would never do that to her again.

“I vividly remember telling Hunter that I was so proud of him,” Jordan said. “Because I did not want to have to tell his nieces and nephews one day that they did not have an uncle if he circled back into his behavior.”

Hunter found a job in Dallas, near where Jordan was attending school in Lubbock. Jordan and Kim came to Dallas to help Hunter decorate his new apartment. They left Hunter with smiles on their faces and hope in their hearts.

“Hunter was confident and looking forward to a new start,” Kim said. “We hoped that a new environment would be exactly what he needed.”

“That Sickening Feeling”

Hunter’s first week at work in Dallas went great. He told his family he loved his job and was jockeying to see if he could get Jordan a position there upon her graduation from college.

He reached out to his family on Thursday, September 14. If there was a problem, the Forakers couldn’t tell by how Hunter sounded that night.

But texts and calls slowed and then eventually stopped, just as they had when Hunter was in Durango.

“We definitely had that sickening feeling that something was wrong,” Kim said.

Hunter didn’t show up to work on Friday and had started drinking again. On Monday, September 18, 2017, Hunter Foraker died by suicide. He was 25 years old.

The Forakers’ Message

The Dallas coroners’ autopsy on Hunter’s brain found evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Perplexed, Kim Googled the degenerative brain disease. Within 30 minutes, she was on the phone with Lisa McHale, CLF’s Director of Legacy Family Relations.

Lisa guided Kim through the brain donation process at the UNITE Brain Bank. Months later, Brain Bank researchers validated the results of the initial autopsy. Hunter was diagnosed with Stage 2 (of 4) CTE.

The diagnosis helped explain Hunter’s erratic behavior, sleep disturbances, mood swings, and substance abuse. Learning Hunter had CTE set the Forakers off on their own research journey. They knew about concussions, but they learned how repetitive nonconcussive impacts catalyze the formation of CTE.

The potential dangers of nonconcussive impacts have changed the family’s view on youth tackle football. Hunter’s youth tackle football career had once brought the Forakers immense joy. Now, the family advocates for Flag Football Under 14.

“Please don’t let your youth play tackle football,” Kim said. “Hunter began playing football at the age of seven and stopped playing at 19. He would have sustained substantially fewer nonconcussive hits if we would have not placed him in youth football and waited to place him in football until his brain was fully formed.”

Kim didn’t know about CTE until after it was found in Hunter’s brain. The family hopes doctors working with former football players struggling with mental health symptoms or addiction consider CTE as a possible cause of their problems.

“Every time Hunter expressed he felt crazy, people brushed it off,” Jordan said. “When he started to drink heavily, it was the easy thing to say he was an alcoholic. When in reality, it was something much, much deeper that needs to be validated and explained.”

Three years after his death, the Forakers remember Hunter for his humility, kindness, and drive. They remember Hunter’s hugs, not his tackles.

“He gave the best bear hugs,” Kim said. “When he held your hand, you felt the love exude from his body.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. Learn the steps at BeThe1To.com.

If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.