New Brain Bank Study Sheds Light on My Past

By Chris Nowinski, PhD

CLF co-founder and CEO

My quest to understand and treat the long-term effects of concussions and repetitive head impacts (RHIs) is not just an academic pursuit – it’s personal. Our team studies individuals with a history of RHIs, a history that I share. Each study helps me better understand my brain health, and what I can expect in the future. Sometimes the news is positive.

Our latest study is not. It serves as a stark reminder that we urgently need effective treatments for concussions and CTE, and we need your help to do it.

Last week I coauthored a VA-Boston University-CLF Brain Bank study led by Dr. Mike Alosco and Dr. Ann McKee that reveals magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can tell us more than we previously knew about the brain health of an athlete who has been exposed to repetitive head impacts (RHIs). The study, Association Between Antemortem FLAIR White Matter Hyperintensities and Neuropathology in Brain Donors Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts, was published in Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology and covered well in The Guardian.

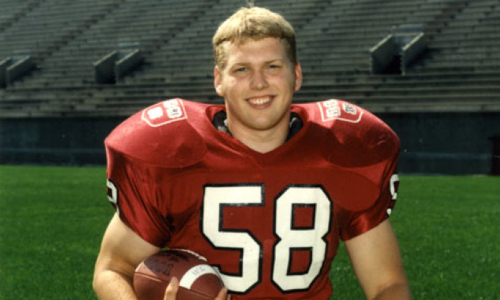

I have about 16 years of exposure to RHIs. Eight years of American football, about five years of soccer with heading, and professional wrestling for three years. I retired from professional wrestling in 2003 due to post-concussion syndrome.

Our research team collected and analyzed MRIs from 75 of our brain donors taken during life and compared them to their post-mortem findings. 67 of the subjects played American football and 70% had CTE.

We discovered the volume of a well-known MRI abnormality, white matter hyperintensities, was related to years of American football play and correlated with neuropathological changes like white matter rarefaction, arteriolosclerosis, p-tau accumulation, and CTE stage, as well as reported cognitive symptoms in symptomatic brain donors exposed to repetitive head impacts. Simply put: the longer the football career, the more white matter hyperintensities found, and the higher likelihood for symptoms.

As a symptomatic future brain donor exposed to repetitive head impacts, this news is not welcome. When I wrote Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis in 2006, I shared a story from my first visit to see now-CLF medical director Dr. Robert Cantu in 2003. He ordered an MRI, and on my way home from the scan, the technician called me and told me I needed to come back for a follow-up MRI the next morning. She wouldn’t tell me why. My imagination ran wild.

While in the MRI the next morning, I could see Dr. Cantu in the next room reading the images live. Long story short, I had so many white matter hyperintensities that Dr. Cantu had to rule out multiple sclerosis. I didn’t have MS. Instead, he told me my brain lesions likely represented dead brain tissue from prior head impacts and concussions. The full passage is below.

At that time, the findings didn’t bother me. What was done was done.

Now, 18 years later, I know what was done is not done. Those lesions may be an indicator of worse things to come.

For those of us who used our heads as battering rams, the clock is ticking. If you’re still on the sideline in the fight against CTE and other consequences of head impacts, it’s time to get in the game. If you’d like to get more involved, email me at [email protected].

EXCERPT BELOW FROM HEAD GAMES (2006)

Dr. Cantu decided to perform an MRI to see if there was any physical evidence of brain damage. I told him that I’d already had one, and it was negative. “While it’s a long shot, sometimes the evidence can take a while to appear, and sometimes you just have to know what to look for,” he said. I left the doctor’s office with more answers, but even more questions.

A few days later, I drove back to the hospital for my second MRI in two months. The MRI process is always impersonal; you don’t know the nurses and technicians, and they don’t know anything about you, save for the part of your insides that a doctor wants to see. This encounter was no different. I slipped into the tube with nary a word spoken. Some people find being trapped in that tiny tube with the loud noises and vibrations of the machine claustrophobic. I’ve had so many MRIs over the years that I usually fall asleep.

This particular morning, the technician interrupted my nap. My new habit of acting out my dreams was causing me to squirm, ruining the MRI images. When I left, I felt anxious about the test results. Yet, since I was confident they wouldn’t find anything wrong, I figured the only harm done was having wasted the morning.

On my way home from the hospital, I got a phone call from a number I didn’t recognize. It was the MRI technician. With a strange tension in her voice, she urged me to return the next morning for another test.

Hesitating, I asked, “Why, did something not work?”

“We’d like to take some more pictures” was all I could get her to say.

I couldn’t tell if she was hiding some huge discovery that they would only tell me in person, or if she honestly didn’t know why they wanted to see me again. Either way, that’s a phone call you don’t want to get. I got more worried when I found out that this busy MRI center (I’d had to wait over a week for my first appointment) had cleared an early morning appointment for me the next day.

From the moment I ended the call, I desperately tried to figure out what diagnosis could possibly require such an urgent second test. Scenarios ran through my mind like flash cards. The stack of cards was short, due to my lack of knowledge of the brain and my lack of imagination. I could only think of two legitimate reasons why I had to go back. Either they had made a mistake, and nothing was wrong (this is what I was hoping for) or they had found a brain tumor (this terrified me). What else could be so urgent that I had to go back to the hospital the next day, but not urgent enough that I didn’t have to go that very second? I figured that a tumor would explain why my symptoms weren’t going away.

I had to stop torturing myself, so I distracted myself by watching a movie, and then tried to go to bed. I figured I’d have plenty of time to make myself crazy on the 45-minute drive to the hospital the next morning. Despite my best efforts, and the usual sleeping pills, I didn’t get much rest that night.

When I arrived the next morning, everything seemed eerily normal. The same nurses and technicians were there. No one was acting weird—as far as I could tell. They slid me into the tube again. There was a mirror over my head set at a 45-degree angle so I could see out past my feet—probably there for the claustrophobics. I had a good view of the technician’s room, where they watch the live pictures on computer screens. In my experience, there are usually only one or two people in the technician’s room. I did a quick head count. One, two, three, four . . .Uh, oh, I thought. That’s too many people.

In addition to the two technicians, I saw Dr. Cantu and another man wearing a lab coat. I assumed he was the doctor scrutinizing the pictures on the screens. No one had told me that all those people would be there. I don’t think I was supposed to know they were there. It was just my luck that two workmen were installing new blinds over the windows that day, so the doctors were in full view. I felt a wave of nausea and started to sweat. I wanted out of the tube.

After twenty more minutes of agony, the test was over. The doctors had left, and the technicians weren’t very talkative. I was told to go up to Dr. Cantu’s office on the eighth floor. That hadn’t been on the agenda either. Not good. When I arrived, there were four people in the waiting room, but I wasn’t even given a chance to sit down. I was whisked right in to see the doc.

By this time, I think I’d stopped breathing. Dr. Cantu must have noticed, because he gave me an overly reassuring smile.

“Don’t worry, you’re fine.”

A wave of relief swept over my body, followed by a wave of confusion. “What did you think was wrong?”

“Well, Chris, you have a few small areas in and on the surface of your brain that show up as white spots on the MRI. Multiple white spots can be early evidence of multiple sclerosis. We had to rule that out, and we did.”

“How?” I asked.

“If you had MS, you’d have a lot more of the spots.”

He seemed satisfied. I was not. “Okay, then what are these spots?”

“Well, the answer is that we don’t know . . . I would venture to guess they’re most likely the residual evidence of tissue damage caused by impacts—concussions. But they look like they’ve been there for a while, so they’re probably not from your latest ones.”

“Does that confirm that I’ve had concussions that I didn’t know about?”

“More than likely,” he answered.

I sat back in my chair and let it all soak in. Sweet. I have dead chunks of brain from all those shots I took over the years. I didn’t know that was even possible. By the end of the week, I would receive a physical copy of the MRI report, and would discover that “a few areas” meant five, and “small” meant as big as 4mm x 3mm on some slides. I didn’t know what was considered big, but I decided that that was all the dead brain tissue I was comfortable having.