AJ Mleczko Griswold led the U.S. Women’s National Hockey Team to a gold medal in the 1998 Olympics and captained the Harvard University Women’s Ice Hockey to a National Championship a year later. Despite never being diagnosed with a concussion herself, her perception of the injury has changed over the years since her kids began playing sports. Griswold pledged to donate her brain to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) research to help widen the brain donor pool and further research on brains that were never diagnosed with a concussion. In this story, she shares how she’s seen concussion culture in hockey change over the past few decades and how she hopes other female athletes will follow her lead and take the pledge to donate their brains.

Posted: February 17, 2017

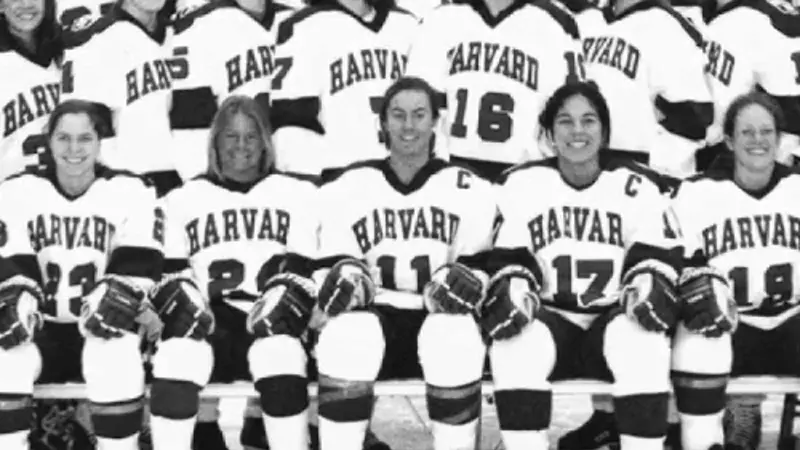

Griswold was a force on the ice. She led the U.S. women’s hockey team to a historic gold medal at the 1998 Nagano Olympics, and a silver medal at the 2002 games in Salt Lake City. In between, she captained the Harvard University women’s hockey team to a National Championship in 1999. That same year she was named the USA Hockey “Women’s Player of the Year” and won the Patty Kazmaier Memorial Award which is presented annually to the nation’s top intercollegiate varsity women’s hockey player.

It wasn’t until the tail end of her playing career that AJ Griswold noticed a change toward concussions. She was in Salt Lake City for the 2002 Winter Olympics and, for the first time she could remember, the team took a baseline test to help diagnose concussions. It wasn’t something she and her teammates spent more than a minute thinking about. They knew to avoid getting a concussion, but mostly because you never knew how much time you would miss if you got one.

Now Griswold has noticed a dramatic shift in her thinking. The mother of four kids, she says concussions scare her more now than they ever did when she was playing. Griswold cares about women’s hockey because it’s given her so much and she hopes by pledging her brain to research, she can leave a legacy of safety.

Why are you pledging your brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation?

What the Concussion Legacy Foundation has done is fantastic. Just bringing awareness to the unknown – the risks and dangers of brain trauma and concussions is great. For me, I care about all sports, but I specifically care about women’s hockey because it was the sport that gave me so much. I want parents to be excited about have their children learn to skate and play hockey. I don’t want them to be fearful for their child’s future.

I have four kids, all four are playing hockey and they’re playing other sports, like soccer and lacrosse, where concussions exist. It’s scarier now, as a mom, than it ever was as an athlete. There is so much great research being done, but there is still just so much that’s unknown about what’s going on. As an athlete, you just sort of play through it and don’t think about the consequences, especially in high school and college. Now, I look at my kids playing and it’s really scary to think that I could be putting them at risk without even knowing.

What do you want your Legacy to be?

I have never been diagnosed with a concussion. So I think it will be important to see what damage had been done with no diagnosed concussions. I think we’re getting better and better at recognizing when someone has a concussion than when I was playing.

As a coach now, if a kid gets hit in the head, I don’t put them back in there. If he or she comes off with a headache – they aren’t going back in. They might say it hurts and then ten minutes later, they’re saying they’re fine. And it really might not be anything, but it’s not my responsibility to take that risk. I mean, it’s youth hockey, they’re only ten. It’s not worth it.

I want to do anything I can in my years after playing to help future generations, whether it be my kids, my friends’ kids, or my kids’ friends. That’s My Legacy.

What has been your experience with concussions?

I was never diagnosed with a concussion in my career. I don’t think I’ve had one, but we really didn’t know much about them and it wasn’t something we were overly concerned with. There were unknowns about it. There was a feeling of ‘you don’t want to get a concussion because then you don’t know how long they’re going to keep you out.’ I don’t think anyone knowingly played through them, but I also don’t think concussions were diagnosed nearly as often.

What’s the major difference between how we view concussions now and how we viewed them when you were playing?

I think there’s more awareness – obviously there’s still so much we don’t know, which is why the research is so important, but there’s definitely more awareness now which is a start.

It’s interesting to me how much more information there is on concussions and head trauma than when I was playing. Which is crazy because there’s still not nearly enough! It wasn’t until 2002 before the Salt Lake City games, the very tail end of my career on the national team, that we did baseline testing. And even then, I don’t know that anyone actually used it. There weren’t as many concussions diagnosed when I played. Looking back on it, I’m pretty sure people had concussions and just didn’t know it.

Unfortunately, it’s taken high profile athletes from the NFL and NHL that have had concussions and tragedy to bring light to the risk of repetitive head trauma.

How does the hockey community view concussions?

Within hockey, Sidney Crosby has brought a lot of attention to concussions and brain trauma and recovery. I think that’s been great because he’s a star and he’s been smart enough to take the time to fully recover from the concussions he’s suffered. That’s the good part. The hard part is when the players who aren’t Sidney Crosby get concussions. They don’t have the same name recognition – they need more protection. There needs to be more player education and awareness of the dangers of concussions.

Would you like to see other prominent athletes step forward and pledge their brain to research?

Of course. I would love to see more athletes, men or women, make the pledge. Men have had the opportunity to play professional and Olympic sports much longer than women, so the pool of retired male athletes is much larger. We’re getting to a time with the Title IX generation – women who played in the ‘90s, a big time for women’s sports – that they’re getting older. I’m hoping more and more women see the benefit of research and are willing to do it. It’s incredibly beneficial.