My journey started and ended like many others who began playing contact sports in the mid 80’s up until retirement as an adult. I knew there were inherent risks in playing contact sports. I knew the chances of being injured were greatly increased the more I played, and the longer I played them. I’ve sustained broken bones, stitches, sprains, and all kinds of ailments related to sports. I do not regret for a second the path I took to get where I am. What I do wish, however, is that the information available today on concussions (the signs/symptoms, reporting, etc.) and potential long term health effects were available to me when I was growing up. Again, I want to be clear: it’s nobody’s fault as to why things played out the way they did. But I want to implore everyone to get a holistic view on concussions through education and research, speaking with experts in this field and to other former athletes who have suffered sports-related brain injuries. Below, I’ll lay out a few scary truths and long-term effects, all of which have stemmed from my personal history of suffering multiple concussions and repetitive head impacts.

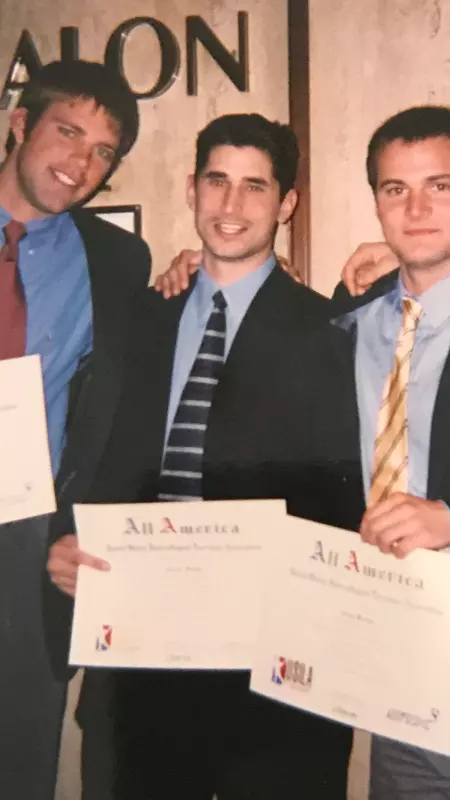

I was a Division I lacrosse player for The Ohio State University. I was also a three-time All-Conference and an All-American my senior year, after which I was drafted into the National Lacrosse League and played one year with the Colorado Mammoth. Sadly, I had to retire at 25 because of countless concussions. Leading up to the final “break the camel’s back” (or put another way “almost obliterate Curt’s brain stem”) hit I suffered, which led to five months of Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS), came a colossal list of concussions that began at a very young age.

I was always athletic from as far back as I can remember. I was on hockey skates when I was two years old, picked for numerous rep teams in multiple sports, always picked first in PE class, etc. However, I gravitated mostly towards contact sports. During my era, I’d hear things like,” shake it off, sit out a shift then get back out there!” or, “oh you just got your bell rung, toughen up!” and of course, “you don’t want to let your team down do you?!” These were ideologies I lived and breathed for the multiple teams I was on. Yet later I came to find out all the while I was doing irreparable damage to my brain and changing my personality along with it.

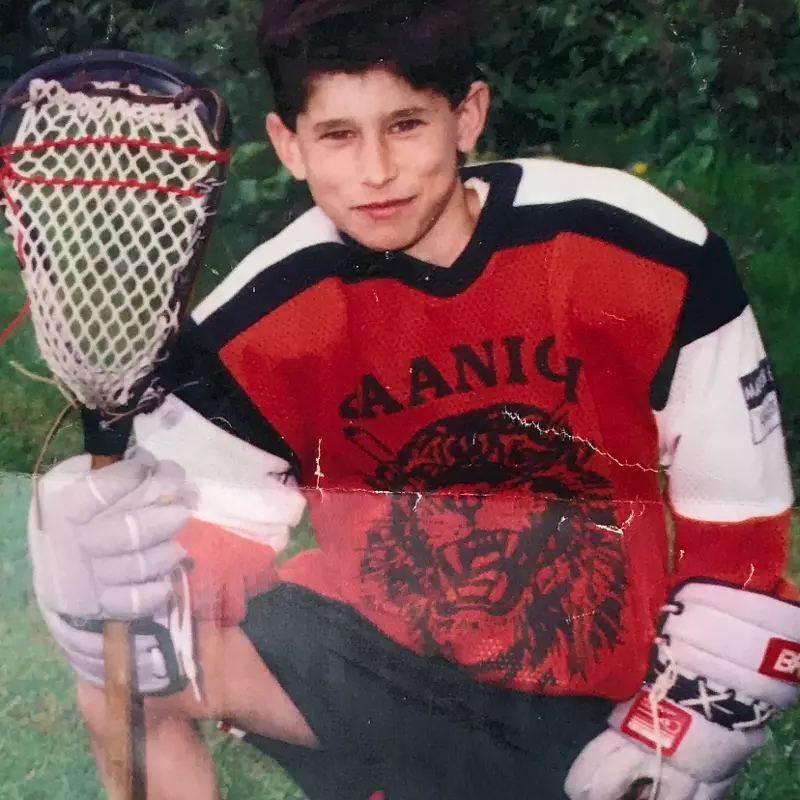

I grew up playing lacrosse, hockey, and rugby, all three of which were relentless when it came to blows to the head. I was introduced to box lacrosse (indoor version) by my second-grade teacher, who suggested it to my parents. She noticed I was faster than most kids and loved to roughhouse with friends during recess. My parents signed me up and I fell in love with the sport immediately. This was back in 1987 when we were allowed to cross-check, slash and body check each other. It wasn’t just legal, it was encouraged! I can vividly remember laying kids out and being praised for it. I also remember multiple times, being on the team bus coming back from tournaments with what felt like migraine headaches. The team trainer would be rotating ice cold cloths on my head to try and alleviate the pain.

When I reflect on those years, I realize it wasn’t until around 12 years old the cascade effects of concussions began to manifest. 1992 was when the intense, social anxiety began to creep in, and my obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) began to reveal itself. The anxiety would rear its head at different times, such as in school when I met new people, and even just attempting to buy a pack of gum from 7-Eleven, to name a few triggers. I was a quiet kid; others called me shy, and I started getting a reputation as an a**hole. This was a major misconception at the time as the behavior I exhibited back then stemmed from the anxiety and overwhelming fear of being in the spotlight (outside of sports). I had certain people I trusted and a close-knit clique, but otherwise, it was difficult to get to know me or get more than a sentence out of my mouth.

And so began a long road of wash, rinse, repeat: I’d receive yet another brain injury, dump some gasoline onto the social anxiety fire and then await the next hit. What’s the definition of insanity again? Oh right, doing the same thing over and over but expecting a different result. As crazy as it sounds, the only thing about this vicious cycle that changed once I got to college was narrowing it down to one sport instead of three.

My time at The Ohio State University was remarkable. I was fortunate enough to play with incredible teammates and under a great coaching staff, while matching up against some of the best players in the NCAA. It would be an understatement to say I was in my element. But as great as it was to play college lacrosse at the highest level, I also suffered seven concussions during my time there. After my third concussion at OSU, another long-term side effect decided to join my symptom “party,” one I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

Trouble with sleep is common after concussion. Sleeping more than usual, or struggling to fall asleep and battling insomnia can happen for a short period of time or can develop into a prolonged issue for those with post-concussion syndrome. But another type of condition that I’m convinced was brought on by my history of head injuries is “Old Hag” syndrome. The actual medical term is sleep paralysis (a type of parasomnia which has been reported following brain injury) and it’s a condition where one is put into a “state,” when either falling asleep or waking up, where they are lucid and aware of their surroundings but paralyzed. The kicker here, and the worst part of sleep paralysis, is the person can hallucinate. My first episode and all others since, have had hallucinations associated with them… and they are terrifying!

When I say hallucinate, I don’t mean friendly cartoons or rainbows in the room. Its alternative name of “Old Hag” syndrome was coined for a reason. It’s associated with occult-like entities such as demons, witches, and paranormal black masses. The medical community attributes this condition to people who claim they have been abducted by aliens, just to offer perspective as to how real it feels when experiencing it. I could speak on this for hours as I still suffer from it to this day, but I encourage all to do their own research on this condition if interested.

As noted above, concussions have led to many adverse long-term effects throughout my life. Over the years, I’ve developed ways to cope with and even overcome them. Just as concussion and PCS symptoms can vary from person to person, so too can their treatment methods. What’s worked for me isn’t a cure-all for others. The key is to find the path that works for you, which is why I think it’s invaluable for all of us to share our stories and struggles, as well as certain methods of dealing with them. For me, it’s been a combination of speaking with healthcare professionals, medication, exercise, meditation, and nutrition, just to name the most impactful. The Concussion Legacy Foundation has been instrumental in my path with finding resources, hearing other personal stories, educating me on specific studies and possible treatments, and ultimately knowing at the end of the day there are MANY people out there who struggle daily with similar issues. If you have never seen the documentary Head Games, it’s incredible and a must watch. It was also the catalyst for me to start reflecting on my concussion history and to start researching the long-term effects of sustaining repeated blows to the head.

My decision to pledge to donate my brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation was an easy one and was based on a few factors. Former football players dominate the discussion when it comes to CTE, and for good reason. There isn’t a higher profile sport, or organization than the NFL in the United States. Highlighting former NFL players who struggle is well documented and highly publicized. Part of the reason I wanted to donate my brain to the Foundation was to show lesser profile sports such as lacrosse can still yield the same results. The second reason was to contribute to ongoing research and the goal of finding a cure.

I’m as certain as I can be I have CTE (seeing how the only way to confirm is post-mortem). I look at my history of concussions, nonconcussive impacts, and the countless times seeing stars after all those hard hits (which I now know is a concussion). Combine those with my present-day issues of forgetfulness, poor impulse control and moments of intense irritability and you’ll understand why I self-diagnosed. It’s a sobering thought and I really hope I’m wrong but I’m not one to live with regrets or worry about things that I have no control over. In regard to my concussion history and probable CTE, all I can do now is share my story and educate others on the risks of playing contact sports, reasons to never hide concussions from your coaches, and to NEVER attempt to “tough through” a concussion and continue playing.

Trust me when I tell you from experience, it won’t end well.