Posted: November 20, 2017

As a kid I grew up in a small town of 2,000 black people in Shaw, Mississippi. I appreciate my hometown because it’s where I learned about how to get through struggles and how to work hard, but there was no diversity and there were few job opportunities. Then my family moved, and I discovered football. I started playing at the age of 10 when I first moved from Mississippi to Bloomington, Illinois. I saw that they had Junior Football League, and I was in awe because we didn’t have those programs when I was growing up. Football gave me a chance to see the world, to dream about seeing something different outside of Shaw. I saw that it gave me an opportunity to stay out of trouble and gave me an incentive to want to do something in life. Football gave me hope.

But I want people, both players and fans, to understand that this is a game. People say so many negative things about the players who are struggling. It hurts my heart to hear, “They knew what they were getting into. They knew what was going to happen.” That’s hard to deal with when the doctor tells you that your seizures are so severe that you may die at any time.

I love football, but we are not prepared enough to handle the risks that come with playing the game. My goal growing up was to use football to get out of poverty, to stay out of the homeless shelter, and to provide something different for my kids. To be in the situation I am in now—it hurts.

My concussions were recognizable, but I wasn’t aware of or able to remember most of them. The concussions came from big collisions when I played strong safety in college. It was a hard-hitting position and there were times I’d be knocked unconscious. Usually I’d be told about them later by teammates or friends. I’d also be told that I was placed back into that same game a few plays afterwards. This happened a few times. After a while, a teammate saw that I was having seizures and reported it to the team, but I was never told this may be serious or that I shouldn’t play anymore.

The consequences of the trauma started to show back in 2009, and they’ve continued up until now. There are blackouts. Memory loss. Seizures.

I wake up every day wondering if I’m going to have a seizure. On days that I have one, I’m unable to do anything. Being a former student athlete, I’ve felt fatigue, but never the type of fatigue that I have after a seizure. Every muscle in your body hurts. You’re in a bed for a full day.

Sometimes I wake up with my friends or my kids standing over me, crying, because I had a grand mal seizure. Or I’ll have seizures where I’m just standing there staring off into space. People wonder what’s going on with me. Sometimes they think I’m being a jerk when I can’t concentrate on anything except the pain in my head.

I usually have at least two or three seizures a week. Some weeks I’m lucky and I’ll have one, but a seizure-free week is rare. I take medications that slow down my seizures and make them less frequent, but they’ve never stopped. I’ve never had anything that stopped my migraine headaches. Some days I can’t handle it. It’s just mentally frustrating to try get through everything and not be understood.

Doctors don’t want me to be alone with my kids. They don’t want me to drive. They don’t want me to work, but social security doesn’t provide much for our family.

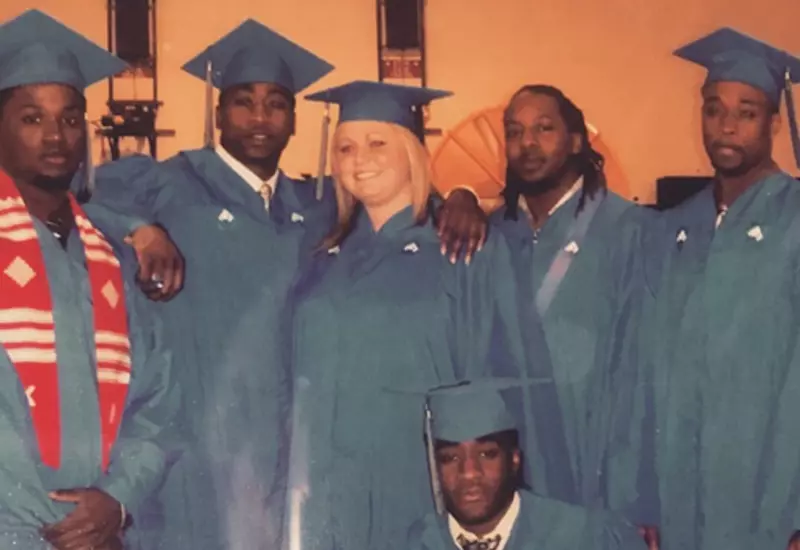

As someone who has pride in his work ethic and wanted to finish school and start a business, it’s hard for me to go through everyday life knowing the doctor has told me I can’t work. I struggled with finishing school due to my brain injury.

I don’t want to be on disability. I don’t want government assistance. But this is the reality of what I go through because the doctor is telling me I can’t work. If I sneak off and get a job to try to work to pay a bill, they would take the benefit. And if I end up having a seizure I risk losing that job because I have to sit at home for days or be in the emergency room to recover.

My family knows I’m worried, stressed, and battling depression because I don’t know how to provide for my kids, or what’s going to happen if I die. Is social security going take care of my kids? Am I going to die in front of my kids? What consumes me is the pain of figuring out everyday life.

When it comes to my family, I’m amazed at the support system that I have. There are situations where guys have committed suicide with their family not being aware of what they’re really going through, and it’s hard for them to get through that. I know my family sees that I’m struggling through pain and these seizures and my depression. It’s really important for them to recognize. But it’s still a huge struggle for us.

When we were in college, I ran away from my wife because I was so embarrassed by the fact that I had seizures, that I had to drop out of school, that I had memory loss, that there were times when I would use the bathroom and I would pee on myself, or throw up from my headaches. I didn’t want her to see me as a weak man. But we fought through it over the last seven years and she stood by my side.