The word “concussion” is on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Avid news-watchers rarely make it a day without hearing about a high-profile athlete’s retirement, or the latest research involving Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Even the average football fan is familiar with the concussion protocol, a reality that didn’t exist a mere ten years ago. The discussion, however, is almost always limited to the upper echelon of the highest impact sport, the NFL. It is important to expand upon this conversation, to let the world know that the phenomenon of repeated blows to the head observed in the NFL isn’t unique to those who earn a hefty paycheck for their skills.

Posted: May 12, 2016

One person in particular is developing the discussion beyond the professional level. This person, Jim Proebstle, is uniquely situated to tell the powerful story of a man who struggled dearly with dementia as a result of concussions and repetitive brain trauma in his athletic career. It is the story of a man who would never make the headlines of the sports section because his name wasn’t widely known. It is a story of rapid decline, radical transformation, and eventual diagnosis of CTE. It’s the story of Jim’s brother, Dick Proebstle.

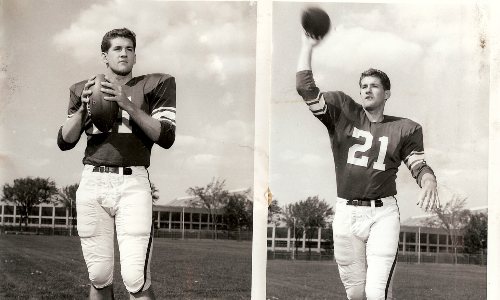

Jim’s closeness to his brother provides an intimate perspective on the world of concussions and CTE. Most stories offer little information about the personal lives of those suffering before symptom onset. Jim, who himself won a national championship ring as a tight end for Michigan State in 1965, has published three books and is an award-winning author. In Unintended Impact: One Athlete’s Journey from Concussions in Amateur Football to CTE Dementia, Jim provides a masterful portrayal of the tragedy of his brother’s life. We spoke with Jim about his book, his brother, and the past and present state of concussion awareness.

What was your relationship with your brother like as a child? How did it motivate you to write Unintended Impact?

I wanted to tell the whole story of concussions and the development of what can happen from repeated blows to the head. My brother and I played grade school, high school, and college football together. He was my older brother by two years, and an extremely talented athlete. Dick was a classic overachiever in everything he did, whether in the classroom, sports or whatever. I really looked up to Dick as a leader. How could this all-American young man end up with a life that contradicted his work ethic and fundamental value system? I wanted to tell his story, as I knew there were other Dick’s out there.

I started writing Unintended Impact right after Dick died. I was in a unique position as we were together in grade school, throughout adulthood, and ultimately to the point where he died. I couldn’t find any reporting that told the whole story of CTE. All I found were bullet points, the last chapter, so to speak. I felt I was in a unique position to speak about the progression of CTE from beginning to end.

What was the first thing you noticed that made you realize Dick might have a problem?

The migraine headaches came first and started right after college. Dick never flunked out of anything, but as a result of the headaches, he flunked out of law school at the University of Minnesota. He just simply couldn’t concentrate. These continued throughout life and we never knew the cause. It was his wife, at the time, that said, “It’s those damn concussions.” And she was right. The significant personality changes, however, didn’t start until his late 30’s.

In the beginning it was just “one-off” behavior quirks- whether it was aggressive behavior, arrogance, or memory issues. With time his interpersonal skills started to drop rapidly. Even his language suffered. From the outside, we thought, “What is wrong with Dick? He seems like kind of a jerk.” The community started to respond negatively, as well, as he fought back. We didn’t know about CTE—these were behaviors that we saw as personality issues, not that something was wrong with him mentally, or part of a disease. Instead we judged him. Looking back, that’s one of the things I regret most. However, Dick and I remained close, and my wife and I were probably the only people that he would trust.

At what point did you say this is a medical issue and we need to seek professional help?

When Dick was about 40, I thought it was odd that when we would visit him he didn’t have any friends. We grew up in the Canton area where he lived. That’s when we said this just doesn’t make any sense. Dick wasn’t the life-of-the-party type of person, but he was a nice guy. He was helpful and generous. He used to have friends, and somehow they just all went away.

Many years later, my dad told my wife, Carole, on his deathbed, that “Something is wrong with Dick.” That was a very declarative statement. We started to pay more attention. But Dick lived in Ohio and we lived in Chicago and it wasn’t always easy to keep track of the changes.

Later in the 1990s timeframe was when Dick’s situation really went off the wagon. The whole value system we grew up with, including what you believe in, what’s important to you, and what you fight for just left him completely. And along with that came additional behavioral issues; slurred speech, balance, significant memory issues, paranoia, judgment and problem solving issues, more aggression—that kind of stuff.

There was nobody telling us that this was a disease—that there was a reason for his decline.

What triggered my mind as to CTE was the Dave Duerson death. We were living in Chicago and the story was in the newspapers. I read it and looked at Carole and said, “That’s what Dick is suffering from.” We quickly became connected with the Concussion Legacy Foundation. At that time it was called Sports Legacy Institute. Everyone was enormously helpful to the family. Dick’s son, Mike, called Chris Nowinski and explained the situation. At that time Dick was in a memory center and long-term care facility. We knew he wouldn’t make it through the year. Even they didn’t know about CTE. Less than a year later, he died.

You played for a national championship team on Michigan State in 1965. What was awareness like in those years regarding brain trauma?

It was different back then, first of all, no one ever called it “brain trauma.” The idea of a concussion was just a temporary disruption to your ability to play—a ding. The treatment was to take someone out of the game or practice and give them a moment to collect themselves—maybe some smelling salts. The person in charge of your wellbeing was yourself because within a short period of time after getting your “bell rung”, the position coach would ask you, “Jim, are you ready to go back in?” And of course, if you ask a player then if he was ready to go back in the game, there was only one answer: “Yes.” We had no education about concussions or what we should do if we got one. We were in the “dark ages” from the 50’s through the early 2000’s. It wasn’t until about 10 years ago that our knowledge changed and our behavior as administrators, coaches, and players slowly started to change with it. We still have a long way to go.

Are there any specific concussions that you remember from your playing days?

Several. Three out of the four that come to mind were in practice—two where I was knocked completely unconscious, one during the game. I was a tight end running a drag route against the flow of the action. I caught the pass in the air but the linebacker hit me perfectly and took out my legs as I went up for the ball. The first thing that hit the ground was my forehead—hard. I was very proud of the fact that I didn’t drop the ball. I was lying on the field flat on my back with the ball on my chest. They took me out of the game, but was back with the next series of downs. Playing hurt was expected. What made the papers was the catch, not the concussion.

What is your opinion about concussion-related injuries for younger players?

I am not in favor of youth tackle football. I think we should start by playing touch football or flag football until high school, at which point we would have an option—an informed choice to play tackle football. I tell people that the only thing I learned playing football at the age of ten was that I was bigger than everyone else. I didn’t learn anything about the game that I couldn’t have learned playing flag football. In fact, I may have learned more. There’s no question that toughness is a requirement for tackle football, but so are so many other skills such as strength conditioning, quickness and footwork, blocking foundation, eye-hand coordination, angle of pursuit, teamwork, execution, timing and discipline, etc. All of these can be learned without the tackle element of football. As a player develops in the game they can make a more informed decision about whether they want to continue with contact football.

You have pledged your brain for CTE research. Could you please speak about your decision to do so?

My brain will obviously be of no use to me at that time. It makes perfect sense to me that a donation can create value for someone else and/or for the sport you love so much. I really didn’t have to think about the decision for very long.

What do you want your legacy to be?

An offensive lineman’s first job it to protect his quarterback. Dick was my quarterback. That says everything to me. Dick always had my back. He always took the high road when I was taking the low road. Some decisions that I would have made without his advice would not have been good decisions. My legacy through Unintended Impact is to honor Dick in the same way that he honored me in life. I would like my legacy to be a meaningful effort contributing to the educational component surrounding concussions. I think football is a great sport and I don’t want football to go away. I believe that player safety and football can co-exist in a sport that breeds excitement. Everything evolves and so will football.