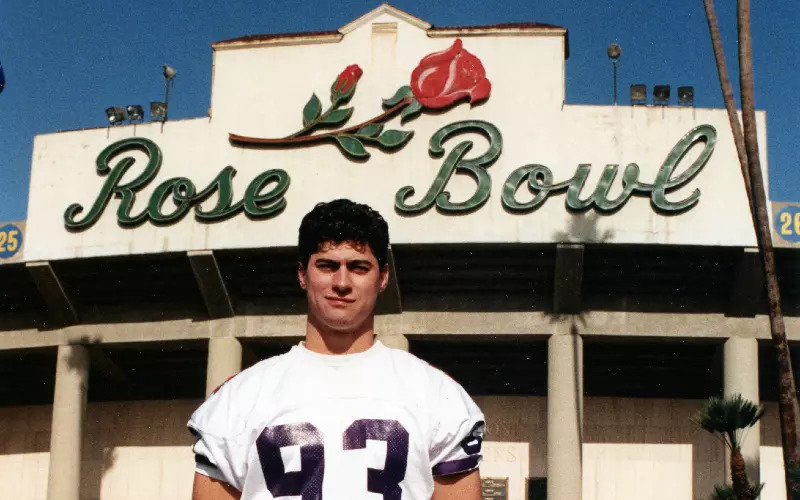

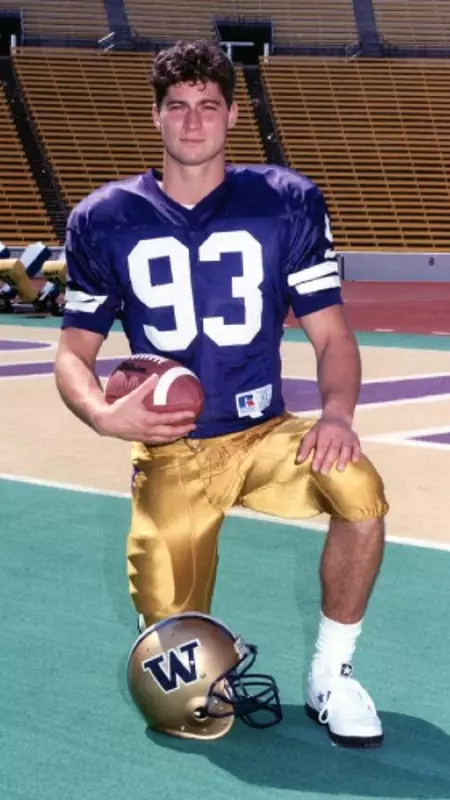

Green graduated from UW in 1993, but his late bloom made him dream of the possibility of playing professional sports. He moved to Massachusetts and tried out for the upstart New England Revolution MLS team. Despite not having played a game of college soccer, Green made the final round of cuts before being sent home.

After a few years playing in a Portuguese American soccer league on the south coast of Massachusetts, Green decided to enter the ranks in the business sector. He joined a small startup company in Arizona before a former boss recruited Green to work with her at Sony. Just as Green ascended from intramural leagues to the Pac-10, he went from a tiny company to interacting with Sony’s top executives in a sales role.

“I took a fearless approach,” Green said. “If you don’t know something, just fake it till you make it.”

Green made it. He thrived with Sony and moved back to the Seattle area around 2005 so he and his first wife could take their kids to Husky games.

In early 2018, Green’s second wife Jennifer noticed Green’s triceps were twitching. Green was totally unaware anything was wrong. The twitching soon spread to other parts of his body, causing concern.

Cutting out coffee didn’t help Green’s twitching. Neither did cutting alcohol.

The twitching intensified and spread further. When Green lost the pinch strength to clip his fingernails, he began to resign himself to the direst cause left on the table.

On August 29, 2018, Green’s suspicions were confirmed. He was diagnosed with ALS, a relentless neurodegenerative disease that attacks nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

Facing ALS with anything but fearlessness would betray who Green had been his whole life. Once he was diagnosed, he couldn’t feel sorry for himself. It was time to get to work.

“The official diagnosis gives you the ability to move on,” Green said. “It enabled me to make a difference and see what I could do while I still could.”

Green’s first step was to connect with someone else with ALS. His old friend Jarrett Mentink had a younger brother who played for the Washington State University baseball team alongside Steve Gleason. Gleason, the famed former New Orleans Saints safety, was diagnosed with ALS in 2011 and has since founded Team Gleason, an organization that improves the lives of people with ALS. Green messaged Gleason and was soon catapulted into the world of ALS advocacy.

In addition to Gleason, Green was connected to Brian Wallach, founder of I AM ALS. He became close friends with Nancy and John Frates, parents of the late Pete Frates. Frates played college baseball and was diagnosed with ALS in 2011 and died in 2019 at age 34. He created the Ice Bucket Challenge to raise money for ALS research. In a twist of fate, Green participated in the Ice Bucket Challenge in 2014, four years before his own diagnosis with ALS.

“I don’t know how I would have been able to get through this without having those connections,” Green said.

Among his extensive list of ALS advocacy efforts, Green is the co-chair for the clinical trials committee for I AM ALS and works tirelessly to reform clinical ALS trials to be more patient-friendly and increase funding so those with ALS can access them. Green says that 30,000 people live with ALS and less than 1,000 qualify for clinical trials each year. He was in a trial last year that seems to have slowed the progression of his ALS.

“The experimental therapies that are in clinical trials are really our only shot at hope,” Green said.

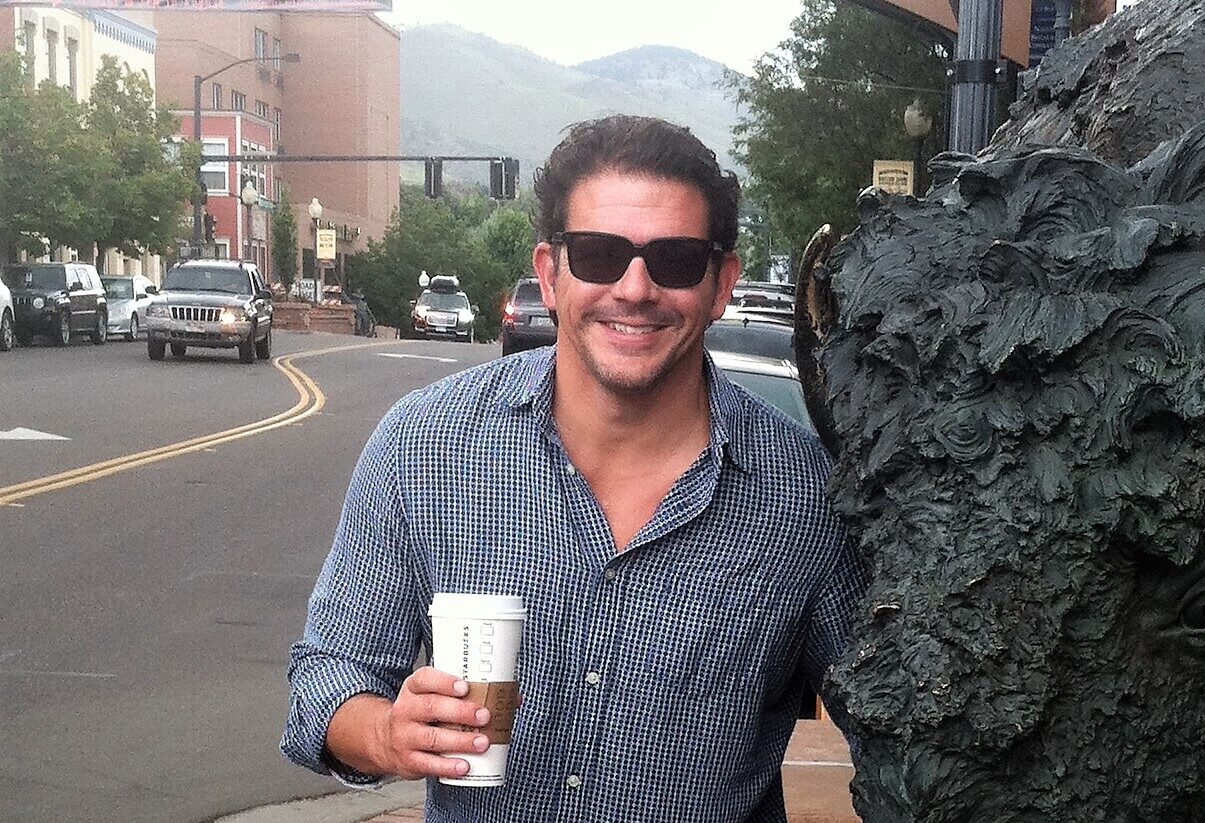

ALS strikes fast and hard. He and Jennifer enjoyed their belated honeymoon in Jamaica in April 2019. At that time, Green could still walk on his own, snorkel, and get in a boat. Now, 18 months later, Green is in a wheelchair most of the day, save for maybe five feet of walking in a walker.

But Phil Green is restricted only in mobility. The same fearlessness that got him onto the UW football team, on the brink of an MLS roster, and into board rooms with global executives stays with him now.

“I have no problem asking for things,” Green said.

Green’s days are filled with phone calls. He recently had a call with Apple’s director of accessibility to encourage the company to create products that work for the ALS community so those with ALS can choose between Windows and Mac. He learned early on that the top ALS doctors in the world were receptive to what he had to say as an ALS patient.

In his hunt for information from the medical community, he connected with Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. After former NFL fullback Kevin Turner died in 2016 at age 46 with symptoms of ALS, Dr. McKee found Turner’s brain had Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). She became the first researcher to report on the association between ALS and CTE.

“This is the best circumstantial evidence we will ever get that (Turner’s) ALS type of motor neuron disease is caused by CTE,” Dr. McKee said after Turner’s diagnosis.

Green never had a diagnosed concussion but remembers having his “bell rung” many times playing at UW and throughout his soccer career. In 2010, Green stopped heading the ball in pickup soccer games because he’d get blurred vision, headaches, and nausea after games.

Dr. McKee connected Green with her collaborator Dr. Gil Rabinovici, the Edward Fein and Pearl Landrith Endowed Professor in Memory & Aging at UCSF. Dr. Rabinovici has studied Green since his diagnosis. Green will be donating his brain to Dr. Rabinovici and UCSF after death to close the loop on the research process.

“I’m committed to helping answer those questions,” Green said. “Anything that I can do to help the science and understanding of both ALS and TBI from soccer and football.”

Green’s ALS is known as “sporadic ALS,” meaning he has no family history of the disease. This sporadic ALS could be caused by CTE, but there are many other potential sources. Green’s history of intense physical activity is also a risk factor. So is a lack of sleep.

Green’s family won’t know if he has CTE until after his death, but he has clarity now that the sports he played need to reform to protect the next generation.

He is a proponent of Flag Football Under 14 and knows many of his former UW teammates share the same opinion. He held his oldest son out of youth tackle football.

“It was important for my kid to understand the game and not how hard to hit people,” Green said. “Tackling is just one small piece of the game.”

As a kid, Green would toss a soccer ball onto his roof practice heading the ball as it fell over and over again. Now he’s glad heading is banned for his youngest daughter’s soccer league.

“It’s like sending your ten-year-old into a boxing ring,” Green said. “That’s probably not the best thing for the developing brain.”

Green knows what he’s up against in his fight with ALS. He has lost many friends to the disease and knows the odds that he beats ALS are extremely slim. But Green, who has never cared about odds, has two sets of goals. One for the rest of his lifetime and another for the future of ALS medicine.

In the short-term, he continues fighting for expanded access trials and patient-centered reforms to ALS care. Both, he thinks, are imminent.

Down the road, Green and the rest of the ALS community hope researchers discover the mechanisms and gene mutations that cause sporadic ALS. With a better understanding of why someone has ALS, researchers can develop more targeted therapies to slow the progression of the disease.

Green will continue fighting with as much as he can give for as long as he can give. Telling his story is another way to fight.

If you’d like to support Phil Green and his family’s fight against ALS, you can support him at PhilYourHeart.org. Green also partnered with Wilson Creek Winery in Temecula, California to release three special Philanthropic wines. Proceeds from the sale of either his cabernet sauvignon, sparkling brut, or the cab/brut bundle go directly to the Phil Your Heart trust.