Danny DiFrancesco was a talented hockey player who always put others before himself. A few concussions early in life led to headaches, impulsiveness, and anxiety. He struggled in his thirties and could not find any answers from medical providers. Danny passed away unexpected in November 2021, at the age of 40. His family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 2 (of 4) CTE. Below, Danny’s mother shares his story to remember his Legacy and help educate others in the community who may be in a similar situation.

Danny was the second of five children. By nature, he was quiet and shy. Sports helped draw him out, and he grew to have many friends. He loved animals, nature, and adventure. His sensitivity showed very early; I remember he was sitting in front of the TV intently watching Sleeping Beauty with the family milling around him on a New Year’s Eve. He was less than three years old. As I started to move him a little farther away from the screen, I noticed his eyes were welled up with tears – just as the prince was waking the beauty. He never lost that sensitivity and became the most compassionate human being.

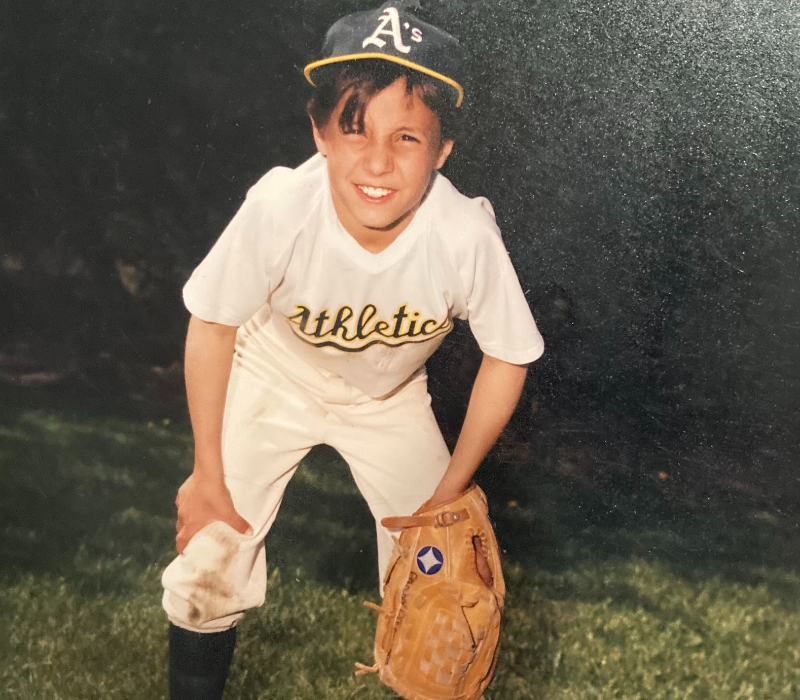

Danny’s first years of school were rough. He had debilitating separation anxiety that caused a sense he was different from others – a feeling he was acutely aware of throughout his short life. When Danny was around nine years old, he suffered his first concussion playing baseball. The protocol then was fairly simplistic: watch for headaches or uneven pupil dilation, and make sure he could be awakened from sleeping. At the age of fourteen Danny was hit by and pinned under a truck while riding his bike. This was his second documented concussion, which also left him with a fractured lumbar spine.

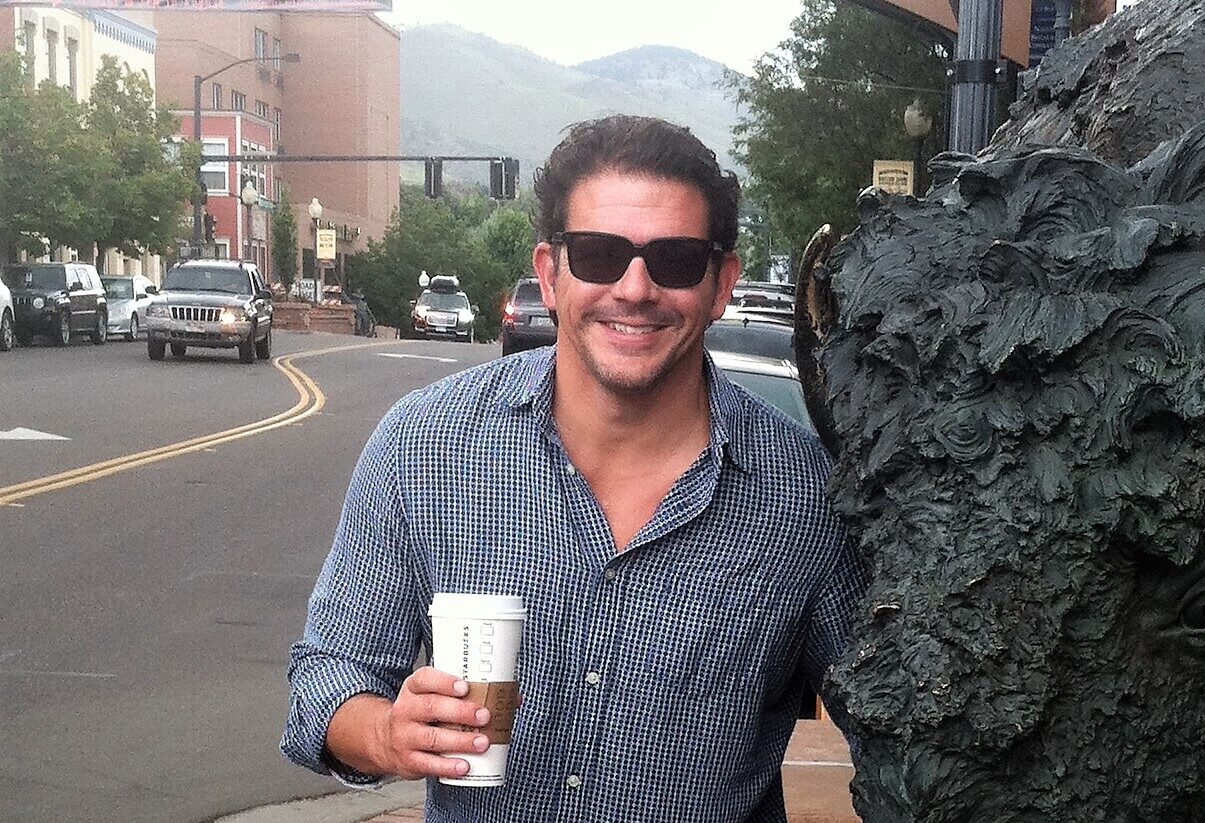

Within two years of the bike accident, we were noticing impulsiveness, outbursts, indecisiveness, and frustration. After punching a window and severing his artery, Danny’s behavior and judgment were being called into question. ADD and PTSD from childhood trauma were the first of many diagnoses. He initially rejected counseling, medication, and labels, furthering his confusion while compounding his anger and reactiveness. His passion for sports, in particular hockey, was his primary outlet. His ethics in sport and hard work never wavered, even though his personal life began to unravel. Our separation and divorce sealed the deal, and soon he found himself in legal trouble and suspended from school. He played harder in hockey than ever and sustained more head injuries. By the time he was 27, Danny felt he had to get as far away from our town and its memories as possible. The next few years seemed to be the best for him. He found and loved South Lake Tahoe. Within a year he worked his way into a supervisory position as security in a casino; he would say he was good at this job because he knew how to relate to the ‘troublemakers’ and effectively deescalate any bad situations. He made fast and close friends with others who loved to snowboard, hike, and fish with him. There were hints of troubles – heartbreaking relationships or annoying roommates, but it all took a turn when Danny’s best friend had to carry him off a ski slope after he tore everything there was to tear in his knee. He had to come home, and his athletic days were all but over.

The last ten years of Danny’s life were a cascade of insensitive or incompetent doctors, never knowing exactly which fire needed to be addressed first. His body and mind were simultaneously torturing him. He saw over two dozen specialists for almost every system in his body. He was hospitalized almost as many times with infections, injuries, disorders, and by then, reactions to dozens of ineffective medications or treatments. The ever-changing diagnoses from mental health providers were overwhelming. He was screaming in his sleep from night terrors. He couldn’t sleep, changed jobs frequently to accommodate his hurting body, and faced evictions due to either financial stress, “noise offenses” when sleeping, or both. Meaningful relationships were tested, leaving some broken. In the last few years, the only people he saw daily were myself, his lifelong friend and brother-in-law, T, or a health provider of some sort. I personally do not know what I would have done without T, Uncle J, or Danny’s friend, J. I don’t know, either, how much more painful it would have been if he hadn’t had their faith in him. And everyone who knew Danny would agree that without his niece, nephews, and little twin cousins to look forward to seeing, his life may have been void of any joy at all. He was keenly aware that family, friends, and the public at large saw him primarily as having troubles due to drinking. With complex PTSD and ever-worsening diagnoses plaguing his life, and the added shame of judgment and criticism, burns and cuts on his arm from self-mutilations were common signs of his internal and external pain. His desperate words, “There’s something wrong with my head,” and “Please, ma, please let me go,” or “Why am I like this” still echo in my head and absolutely break my heart.

Danny never stopped trying to find help, but he had lost hope. He became suicidal and made multiple attempts, even jumping out of my moving car. He was often triggered by the sight of a cop car, a knock on his door, or even thinking about another invasive or intrusive doctor appointment. A year or so before his death we had both watched a documentary about CTE, and Danny brought the subject up with his psychiatrist via Zoom. I happened to be on the call as well when this extraordinary man responded very compassionately and firmly. Dr. G had been reviewing the past two years of notes (he was relatively new) and asked Danny if his neurologist had done any brain scans or studies. The neurologist had ordered an MRI years earlier at my request, but said the results were unremarkable. The psychiatrist then asked Danny why it appeared that his primary was not treating his hypothyroidism. Or his anemia. Or his high cholesterol and blood pressure. Only one other specialist – his orthopedic surgeon – had ever approached Danny with simple human compassion and concern. The psychiatrist’s next comment was directed to me: Find him new, reputable doctors immediately, and get his brain looked at again. We did manage to get his brain looked at, but only after he had died suddenly. After 10 months we still have no answers from the medical examiner, or even an investigation into his death by local police. He had said many times that he just wanted to donate his organs to help kids. My daughter (almost by divine intervention) remembered to relay Danny’s wishes to the coroner. It was too late to harvest any organs, so she immediately pulled up the website for the Boston University CTE Center. This he could do. This is how we came to learn he had stage 2 CTE; bittersweet to finally have a diagnosis that explained so much and felt like vindication for him, but also unleashed a tidal wave of guilt and regret on family and friends who loved him so much.

There is an indescribable tragic cycle that starts with a head injury. The cycle of alcohol, or abuse, or judgment, or shattered families and relationships. The cycle of being misinformed and misunderstood. This is a horrifying and tremendously sad story. But Danny’s life absolutely had purpose. His life left us with endless and indelible joyful memories. He was a skillful and determined Easter egg hunter and there was no theme, costume, or competition he was too proud to embrace. He was known to scan the fridge and cupboards for so long thinking about what to eat, that inevitably he would walk away empty-handed mumbling, “I’m full.” He was a master at moving furniture – the bigger the couch and steeper the stairwell, the better. He always loved a good puzzle.

Our Danny was more than a good person. He was the one who never hesitated to help others or recognize someone else’s distress. He befriended and shared his food with local homeless people. Being judgmental of others was not in his nature; he was charming and could genuinely connect with anyone. He helped anyone stuck in the snow. He helped before you even knew you needed help. Despite his chronic pain he was the first one on the floor to pet an animal or play with a child. Despite his emotional pain he would take great joy from sitting at the kids’ table. He was colorful and quick with a laugh; smart, hilarious, clever, observant, and kind. He has opened so many hearts and minds to new insights on love, patience, and acceptance. His brain donation has helped educate and inform our family and community. I’m so sorry we can’t tell him how devastating his death will forever be. How painfully aware we are that we let him down. How enormous the hole is in our hearts he left behind. How much we love you, Danny.

You never seemed to understand why I was, and still am so proud of you. You are a warrior, and I celebrate your life and Legacy, and especially your strength and spirit. I will always love you. ~Ma