Ed Wolf was an athlete, a serviceman, and above all, a family man. During his life, he gradually began to experience the symptoms of CTE and his family chose to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 3-4 CTE. Below, his wife, Mary Jo, shared his story as the final contribution of Ed’s Legacy.

Ed was a man of many talents who excelled both academically and athletically. He held an impressive list of accomplishments in his lifetime, both on and off the field. He was a minor league baseball player, a four-sport varsity letter athlete, a member of the Army National Guard, and was inducted into two local halls of fame.

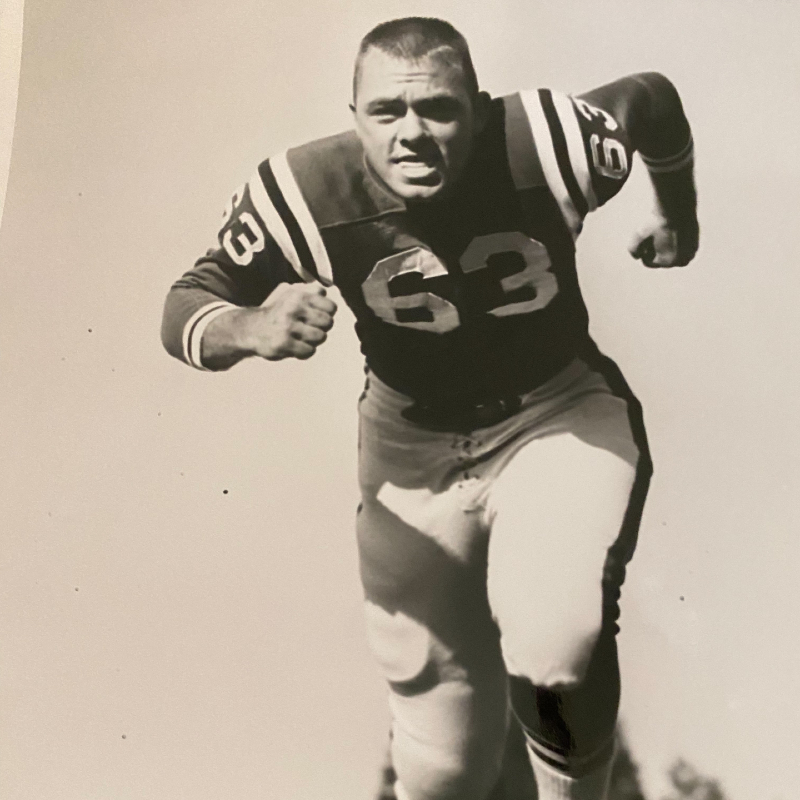

Born in 1939, Ed’s love of sports began when he started playing football in grade school and continued to play through high school and college. He was first team all-city for football, but his athletic accomplishments did not end there. During his time at Deer Park High School in Cincinnati, Ohio, he lettered in four sports: football, baseball, basketball and track.

Ed then attended the University of Cincinnati where he continued his athletic career and lettered in football and baseball. He was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity and the Sigma Sigma honorary fraternity.

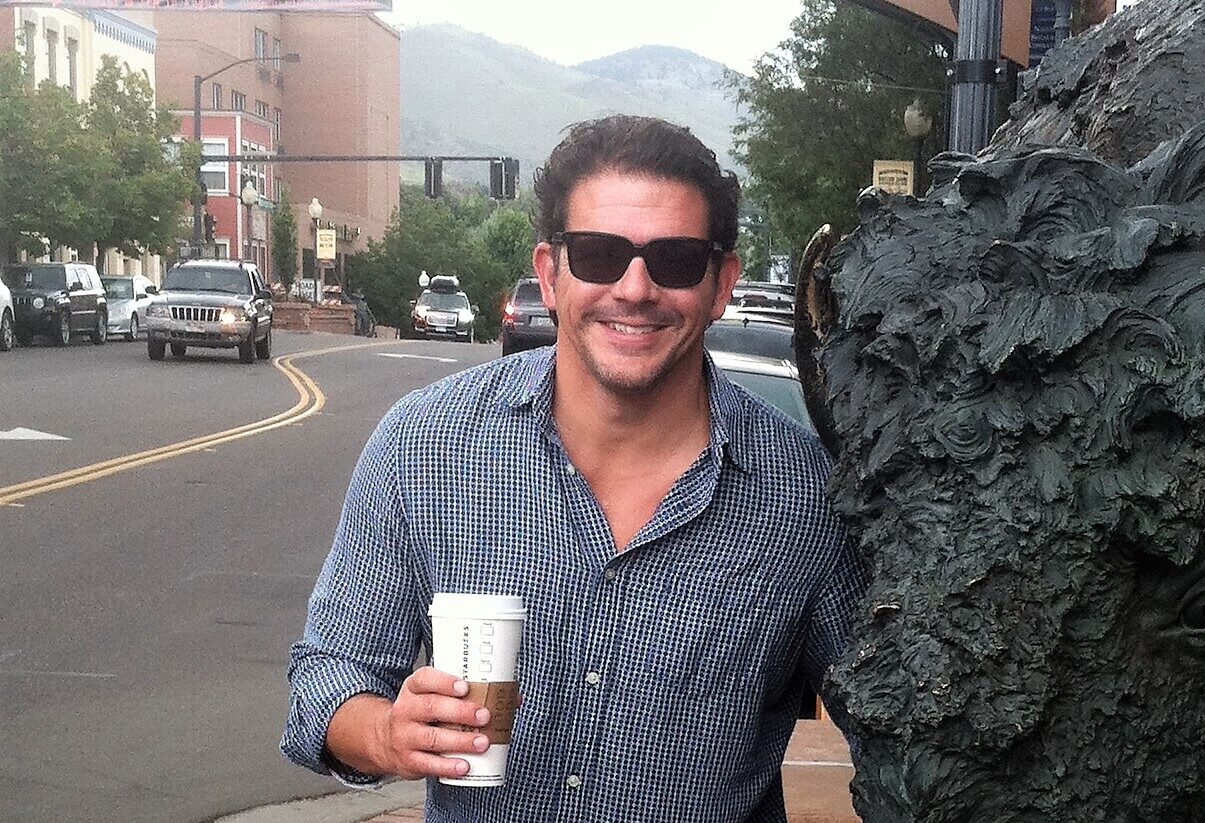

He later signed with the Houston Colt .45s, a minor league baseball team, and was a catcher for two years. His years of playing sports and childhood concussions led him to experience many head injuries. After his time in the minor leagues, Ed was in his twenties and gravitated away from sports. He joined the National Guard and proudly served for six years. We met during our college years, married, started a family and Ed began his career. He pursued his MBA at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management and led a successful career in executive sales and marketing. He was the director of the Port of Wilmington. He traveled the world and enjoyed the challenge of this multi-faceted, but politically vulnerable job. In the ’90s, Ed reentered the job changing pattern. We had relocated many times to Kentucky, Illinois, Florida, Delaware, and back to Cincinnati for his retirement. It is difficult to pinpoint but somewhere in this history was the onset of the symptoms. I remember his comment, “I just can’t seem to find the right situation where I can be all that I want to be. Something seems to be blocking me, something seems to be getting in my way.” Overall, Ed did not appear to be conscious of the challenges of CTE.

Looking back, inexplicable behaviors seem to form a profile indicative of the disease. In his later years, Ed displayed cognitive impairment with the inability to problem solve or strategize. He loved to sing and was a member of his local chorus. But after two years he could no longer participate. The effects of the disease took its toll in many ways.

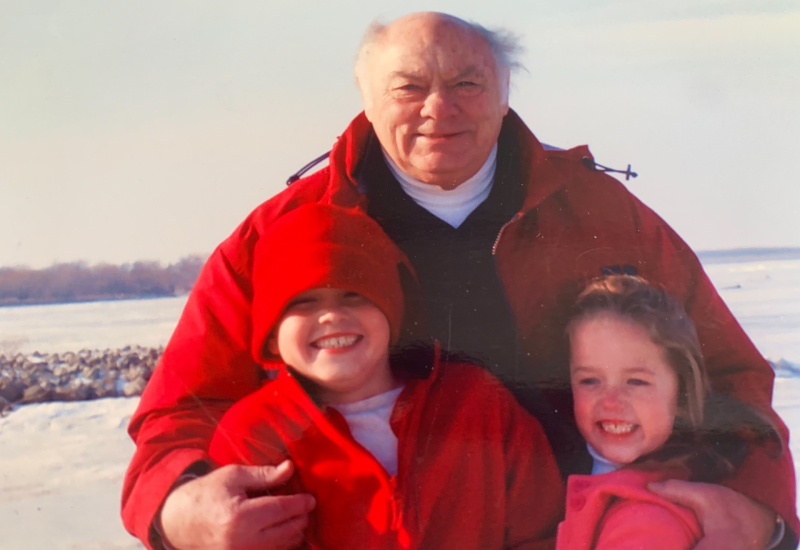

We were fortunate because the slow onset of symptoms meant it did not have a great impact on our family life while raising our children. Looking back, I remember he experienced some agitation and depression, and it was in the last two decades of his life that we noticed changes in his personality and behavior. He was a humorous guy and relished the role of loving father and coach for the kids’ baseball, soccer, and softball teams. His daughter Leslie relates, “He was the dad who was always there, and that presence gives much joy to the memories of our childhood and adult life.”

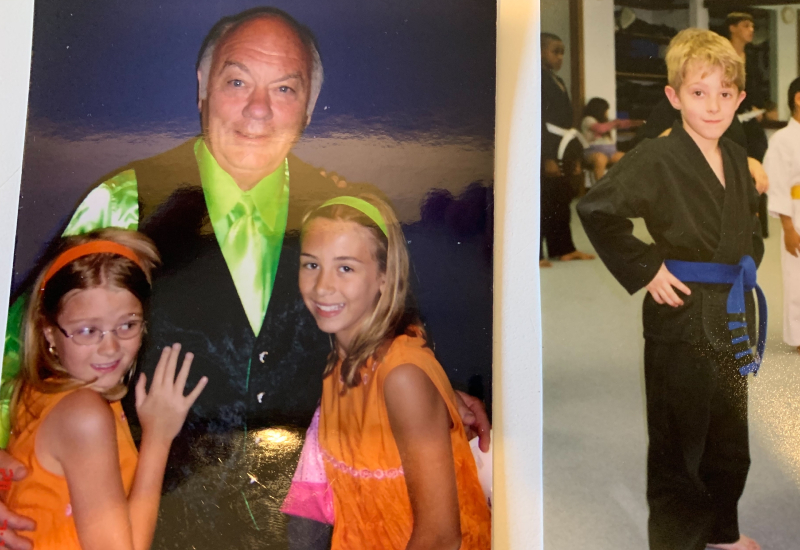

Ed was an all-around good man. The impact of the disease was irrelevant to that goodness. He had many friends and loved and cherished his three children, five grandchildren and his grand dogs. These relationships brought him much joy throughout his life. The times Ed spent with his family were the times when the symptoms and challenges he experienced from CTE seemed to be minimal. It felt like a true gift to know that despite the changes happening to Ed, his family meant so much to him.

During his life, Ed worked with a neurologist who helped us narrow down the cause of the dementia and we knew CTE was a high possibility. In retrospect, it is clear how much of his behavior was likely caused by CTE and it is hard for families to watch the demise of a loved one and not know what is happening to them.

A few years prior to Ed’s passing, our daughter, Wendy, discovered the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the UNITE Study at the Boston University CTE Center. She registered his willingness to participate and made the brain donation possible. Though his CTE diagnosis wasn’t a surprise, it was difficult for us to accept.

For him, the playing of the sports, the recognition of his abilities, the joy that he got, the commitment, the determination that he had, seemed for him to be the reward that he remembers. The actual outcome and the price that he paid for that, I don’t think he was ever cognitively aware.

It is important that athletes know the risks of sports from an early age. Our family is happy to know that Ed’s final contribution and legacy are part of crucial CTE research. There are so many famous athletes that have contributed, and it was just very exciting that our guy, his brain, was just as valuable. That made us feel that this was his very best contribution that he could make.