Fulton Walker played college baseball and football for West Virginia University in the late 1970’s and was drafted to play both sports professionally before choosing football. He played in the NFL for seven seasons before retiring in 1986. By age 50, he began struggling with memory and executive functioning skills and was diagnosed with dementia. At age 58, Walker died unexpectedly of a heart attack. His family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). His son Kevin is telling his story to share his Legacy and to advocate for Flag Football Under 14 and early action to support a parent with CTE.

Before Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, Tim Tebow, or Kyler Murray blurred the lines between professional football and baseball, there was Fulton Walker. Walker grew up in Martinsburg, West Virginia and started playing tackle football at eight years old. He raced past defenders in youth football and shined on the baseball diamond. His exploits became the stuff of legend. Walker’s son Kevin was born when Fulton was in high school, so Kevin was well versed on his dad’s athletic prowess by the time he grew up.

“I was sitting in one of my P.E. classes and the teacher tells me how my dad was the best athlete to ever come out of West Virginia,” Kevin said. “He was saying, ‘I watched him play a baseball game one day and rob a home run and then that night run a punt back.’”

Walker was a four-sport letterman for Martinsburg High School and a key player at home as well. He would rush back home from games and track meets to mow his family’s yard and to split wood for a fire.

After he graduated from Martinsburg, the Pittsburgh Pirates selected Walker in the 25th round of the 1977 MLB Draft. He opted instead to attend West Virginia University, where he watched many football games as a kid and where he could play both football and baseball.

Walker became one of the first Black athletes to play for the WVU baseball team. In football, he played running back and returned punts for the Mountaineers as a freshman. He made headlines his first season by returning a punt 88 yards for a touchdown against Boston College.

He switched to defense his junior season and held a larger role on the team. Coach Don Nehlen arrived at WVU for Walker’s senior season and immediately counted Walker as one of his favorite players.

“You have certain guys on your football team that really enjoy the game – it doesn’t matter if it’s Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday or Saturday, they like to play and Fulton was one of those guys,” Nehlen would later say. “You’d go out there on Tuesday and he was grinning and then on Wednesday he was grinning. He was very popular on our football team.”

Walker’s popularity was not contained to the Mountaineers locker room. Kevin Walker saw his dad get stopped by friends and strangers his whole life. Fulton could not go to a cookout or a grocery store without someone wanting to stop and chat with the local legend.

“He was always pulled one way or another for conversation and one minute turned into 30 minutes and we’d be hours late for things. And he would always stop. He always had time,” Kevin said. “He’d never act like he was Superman. You know, he was just a regular old guy from a little country town.”

Walker’s senior season at WVU was a huge success. He finished with 86 tackles and two interceptions for the team in a season that would be credited with turning the football program around. The Miami Dolphins selected Walker in the 6th round of the 1981 NFL Draft.

His cool, upbeat, down-to-earth personality made him just as much of a locker room favorite in Miami as he was in Morgantown. Walker’s next-door neighbor in Miami was Dolphins star quarterback Dan Marino. Walker and Marino bonded over the rivalry between their alma maters, Walker’s West Virginia and Marino’s Pittsburgh, which is serendipitously known as “The Backyard Brawl.”

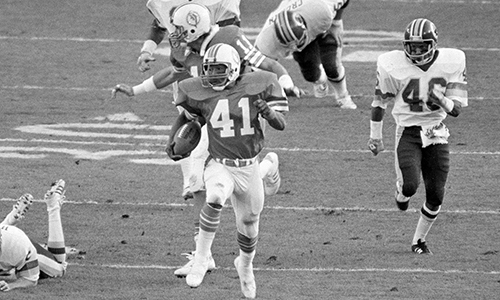

Walker played five seasons with the Dolphins as a cornerback and a special teams ace. His career highlight came when he became the first player to return a kickoff for a touchdown in a Super Bowl when he sprinted 98 yards for a touchdown to give the Dolphins a 17-10 lead in Super Bowl XVII in 1983.

No one could catch Fulton Walker that day, or most days for that matter. But Kevin did. Once.

“We were walking to my aunt’s house and he was like, ‘Man you wanna race?’ and I said let’s do it,” Kevin said. “And we ran pole to pole and I beat him.”

Walker tried to put an asterisk on the defeat by claiming he did not have the right footwear for the occasion. But 13-year-old Kevin let everyone in his junior league baseball dugout know he beat the Super Bowl record-holder.

After two more injury-riddled seasons with the Los Angeles Raiders, Fulton Walker retired from football in 1986. Playing primarily special teams, Walker only saw the field for a handful of plays each game. But the impacts he was involved in on kick and punt returns count among the fastest and most violent in the sport. After football, Walker had his ankles fused, his vertebrae fused, and took more than a dozen pills a day to alleviate pain in his neck and to help him sleep.

“His injuries, you’d think it was from motorcycle wrecks or something. But he just played football. So yeah, you’re tough. But your body can only take so much,” Kevin said.

With football behind him, Walker went back to WVU to earn his master’s degree in Industrial Safety. Kevin says Walker was extremely sharp and could handle a very large workload. For years he managed a trucking company in West Virginia and then became a teacher and coached football and baseball back at Martinsburg High. He satisfied his itch to stay physically active by playing golf and softball as often as he could.

Walker then started to struggle with his memory. He would forget where he put his keys, leave his car running, go to the store and forget why he went by the time he got there, and repeat himself in conversations. These short-term memory issues affected his ability to work. He would forget how to use certain computer systems he mastered the week before. Eventually, the state of West Virginia determined he needed to go on full disability.

The memory battles caused Walker to get frustrated with himself. He took his frustrations out on others and slipped into depression.

“My problem is I can’t multi-task. I can’t get my brain full of stuff because it puts me in a place of confusion,” Walker said in an interview with Katherine Cobb in September 2016. “Stuff in the present I can have problems with, but stuff in the past, I still have good recollection. I have to write things down now, so I remember. It is what we guys have been going through but we didn’t understand what was going on. It’s been frustrating and overwhelming sometimes.”

When Kevin saw his dad almost daily, his decline was less noticeable. But when he moved away to North Carolina and saw his dad less frequently he noticed how steep his fall was. Kevin knew his dad needed help and set up appointments for neurological testing in Orlando and Atlanta. Those tests showed Walker suffered from dementia, which qualified him for benefits from the NFL’s “88 Plan,” named after Hall of Fame tight end and CLF Legacy Donor John Mackey.

On the night of October 11, 2016, Kevin called his dad to let him know he would need to switch cars with him for Kevin’s upcoming work trip. Kevin arrived the next morning and grabbed the keys his dad had left out on the counter. He chose to let his dad sleep rather than to say goodbye. As Kevin was driving home from the meeting later that day, he received a call that Fulton was being rushed to the hospital.

Kevin drove to meet his dad at the hospital, but it was too late. Fulton Walker was pronounced dead on October 12, 2016 at 58 years old. He died from a heart attack.

Walker’s funeral in Martinsburg was full of testaments to his humility, generosity, and ability to make those around him feel like they, not him, were the Super Bowl record holder in a conversation.

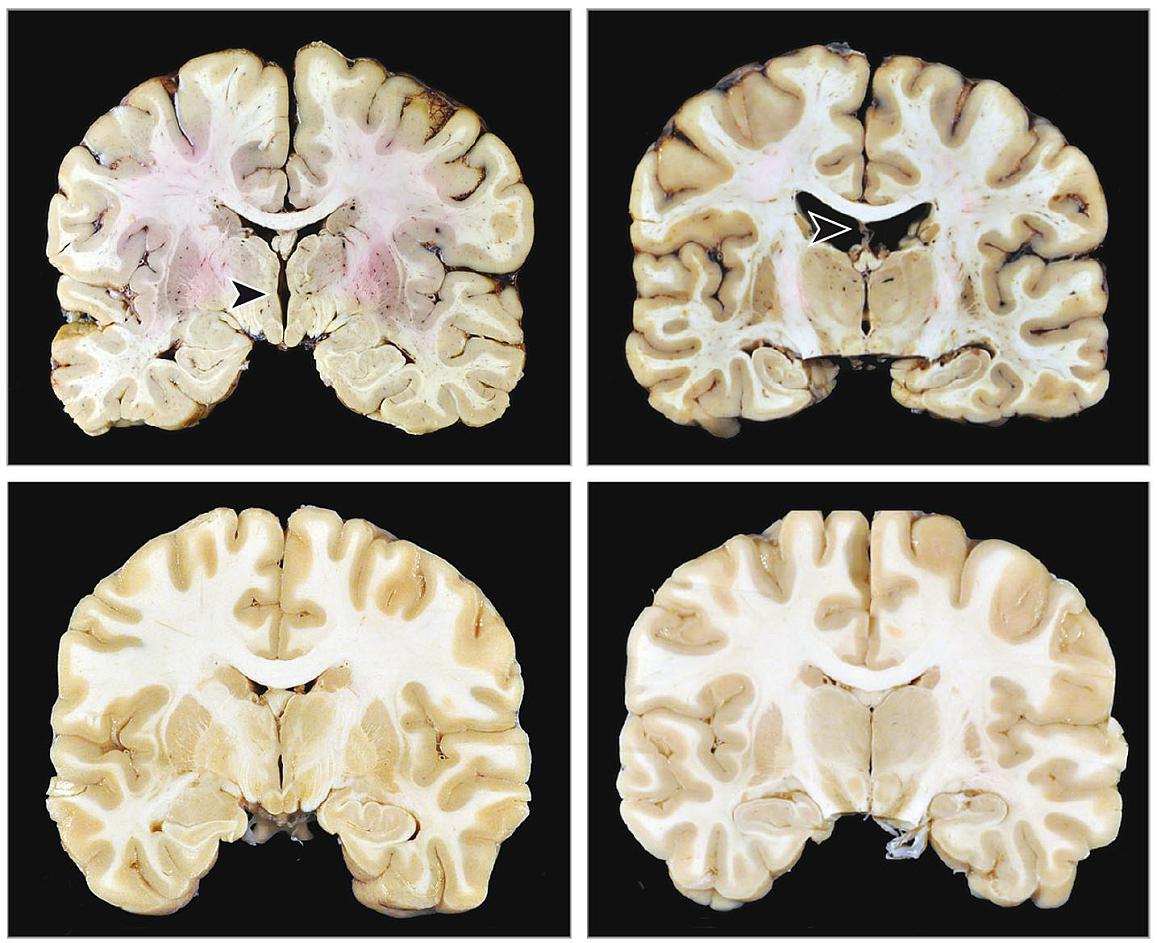

Kevin and the family decided to donate his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank after his death to see if his cognitive and emotional problems could be attributed to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, diagnosed Walker with mild CTE in his dorsolateral frontal and temporal cortices.

Fulton Walker loved football too much for the family to hold ill will against the sport for its role in his CTE. Instead, Kevin believes his dad would have opted to play flag football as a kid and would advocate for the next generation to do so as well. Kevin points to Barry Sanders’ training in flag football to increase his elusiveness to show how playing flag football improves ballcarriers’ open-field skills.

Kevin knows that playing pro football when his father did and now are two different financial realities. He thinks today’s NFL players have the liberty of shortening their careers and protecting themselves in a way his father’s generation did not.

To other children who have parents that spent a life in contact sports and who might be at risk for CTE, Kevin urges you to stay aware, and take action to get help sooner than later if you see signs like mood swings or forgetfulness.

Kevin will always remember his dad for his work-ethic, humility, laid-back personality, and as a pioneer for two sport athletes.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms or possible Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.