Gus Lee was a kind, quiet defensive back at the University of Richmond. Lee battled homesickness in his sophomore fall term but still thrived academically and socially. On December 9, 2018, Gus Lee took his life at age 20. Lee’s parents, Phyllis and Chris, donated his brain for research at the UNITE Brain Bank. Phyllis Lee is sharing her son’s story to shed a light on Gus Lee’s mental health battle in hopes other athletes learn the importance of speaking up if they’re struggling.

This article adheres to the Suicide Reporting Recommendations from the American Association of Suicidology.

Monday, December 10, 2018

Anxious and exhausted, Phyllis and Chris Lee decided to finally go to bed at their Vienna, Virginia home.

“If he’s going somewhere, he’s coming here,” Phyllis said. “He’s gonna come home.”

Gus Lee had finished his second football season at the University of Richmond and was set to take two finals that day. Finishing finals would mean he was one step closer to what was shaping up to be a fun and well-needed winter break. But texts and calls the previous day from Chris and Phyllis went unanswered.

Phyllis was worried after Gus’ roommate said he hadn’t seen Gus in a whole day. After a quick check with local friends and relatives, the family made the decision to involve the police in the search for Gus.

Jumping in

Augustus “Gus” Lee was the youngest of three and developed the kind of bravery that comes from watching older siblings. The Lees belonged to a neighborhood pool in Vienna. One day, neighborhood children took an interest in the daunting high dive. A five-year-old Gus was the first to go up, calmly, without saying a word.

Chris looked on in preparation for a last-second backout, but his son jumped off the diving board and into the pool. Gus blazed a trail and a cascade of other kids followed his lead.

Young Gus was a teacher’s favorite type of student and eventually a coach’s favorite type of player. He may not have been top of his class, but he listened with great intent.

The Lee family soaked up their time together before college splintered everyone’s availability. They hiked often and took many vacations to beaches along the east coast. The Lees were not the type to plant their chairs in the sand for hours on end. The beach was a recreation center. The family played football, kickball, racquet sports, and eventually started surfing.

For Gus, the beach was just another field to excel on. His amazing speed was on full display in whatever sport he picked up. Gus stood out from the time he was barely taller than the soccer ball he was kicking down the field.

The hits

Gus was knocked out cold in the middle of the field in an eighth-grade lacrosse game in 2013. Chris and Phyllis looked on while Gus’ coaches came to his side. Eventually, Gus sat up. He could answer who he was and where he was, but the score of the game he had just exited was a total mystery.

At the hospital, doctors determined Gus did not have a brain bleed. He was alert and talking. The best sign to Chris and Phyllis was that Gus was hungry, which meant the always-ravenous teenager felt like himself. ER doctors told the Lees to take him home, let him rest, and let them know if anything changed.

Two days later, Chris had a physical with the family doctor. Gus’ injury came up in conversation. The physician referred the family to a sports medicine specialist to assess Gus.

The specialist determined Gus was suffering from a concussion. No school, no sports, no activity until Gus recovered.

Gus returned to school about a week later and didn’t seem to have any lingering problems. But the specialist still decided sports were out of the picture. It took nearly six weeks for Gus to return to sports.

The delay shocked the Lees. He seemed fine. Gus said he was fine.

Gus would put football on pause after that season but kept playing lacrosse year-round. The concussion would be the only one Gus was ever diagnosed with, but he was involved in several high-impact collisions, including one during an indoor lacrosse game and another big hit in college.

At the time, Gus may have only had to miss a couple of plays or stay down for a few extra seconds on the turf. But Phyllis now believes some of those hits may have been undocumented concussions.

The odd couple

Gus transferred to Paul VI Catholic School in Fairfax, Virginia before his junior year of high school. Before the year, he started training with the Paul VI lacrosse players. Many of them also played football. Seeing his tremendous athleticism, they urged Gus to come out for the football team.

Initially, Gus declined. But Gus decided at the last minute he wanted to join the team in summer practice.

Gus became the perfect target for Paul VI quarterback Jimmy Check. Check could throw deep and Gus could go get it. Check, tall and lanky, and Gus, short and stocky, may have looked like a funny pair but the two boys were highly compatible. They were constantly practicing routes and perfecting their chemistry. Check to Lee became a combination worth watching.

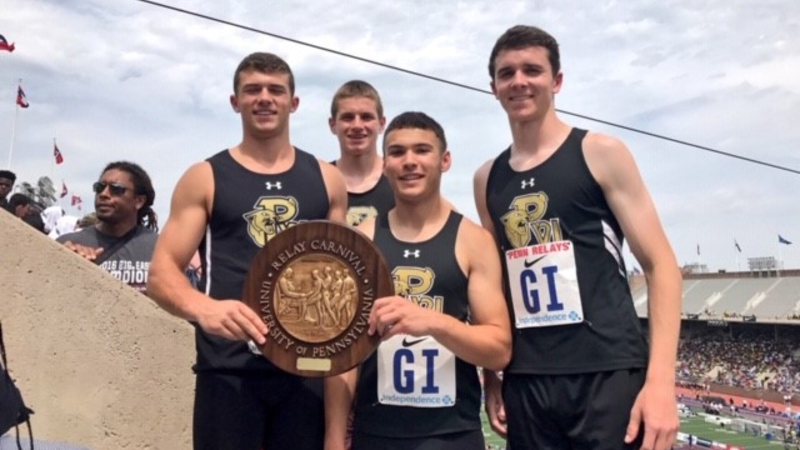

Gus’ senior season at Paul VI was one for the books. He was named captain, set the school record for receptions with 79, and made the VISAA Division I All-State First Team.

Gus checked a lot of boxes for your classic high school jock. He was handsome, athletic, and well-liked. Yet he lacked any of the undesirable qualities that come with the stereotype. He remained a diligent student. He was quiet. He was even a bit quirky. He also cared about every student at Paul VI, whether or not they had letterman’s jackets.

In need of an elective his senior year, Phyllis encouraged Gus to participate in Paul VI’s Options program. Part of the program connected Paul VI’s general education population with their special education students. Gus was a kid of few words, but his ability to listen made him a favorite among the Options students and faculty.

Richmond

Gus wanted to be a D1 athlete from an early age. His family thought it would be lacrosse that helped him achieve that goal. But the impressive stats from his senior football season garnered some last-minute attention from college scouts. He and his high school coach met almost daily discussing recruiting opportunities and finding a school that was a good fit academically and would afford Gus the opportunity to play and contribute to the success of the team.

Richmond fit the bill perfectly. Gus knew his family thought highly of the school already and after a day on campus with the coaching staff he happily accepted their offer to walk on to the football team.

Gus enjoyed his coursework at Richmond. He enjoyed the team workouts and thrived in the weight room. He did not particularly enjoy redshirting and having to watch the game from the sidelines. He had been recruited as a slot receiver but the coaches switched him to defensive back. He worked hard to learn the new position and adjusted quite well.

He liked meeting new people. He liked going to parties. But all the newness wasn’t enough to drown out how much he missed what he had grown comfortable with at home. He missed his high school friends. He missed his bed. He missed the family dog, Beanie.

By that point, Gus was Phyllis’ third child to go through the college adjustment process. This homesickness didn’t seem like anything out of the ordinary.

In the annual Spring Game on April 21, 2018, Chris and Phyllis finally saw Gus dressed in full pads for the Spiders. He intercepted a pass, recorded seven tackles, and was named the game’s defensive MVP.

Gus was back home a few weeks later but didn’t have much time to recharge. He got a summer job digging wells. Gus worked long, hard hours in the hot Virginia summer and returned at night covered in earth. Well pumping took Gus into late June before he got time to spend a few days with friends at the beach in Wildwood, New Jersey and a few more at the Outer Banks. Then it was back to Richmond for a summer class and the start of summer workouts.

The 2018 season opening game was nerve wracking for the entire Lee family. Chris and Phyllis didn’t know what to expect. Would Gus even see any playing time? But they happily drove to UVA in Charlottesville where Gus’ older sister Gillian had already graduated and his brother Jackson was in his fourth year.

The family all watched Gus play on the kickoff and kick return teams. He made several appearances on the Scott Stadium video board. The Spiders did not win that night but Gus made sure to find his parents after the game for a hug and a quick check-in before boarding the team bus, a ritual they repeated each game for the rest of the season.

“I’ll be home in an hour.”

Gus got sick with bronchitis during the season and came home to Vienna to rest. After he recovered and was back on campus, Gus and Phyllis began speaking often on the phone.

These calls elucidated how Gus was again struggling being away from home. Gus, who was usually to food as a Dyson vacuum is to dirt, had little appetite and was worried about losing weight.

The Spiders’ season ended on November 17, 2018 with a hard-fought win at William & Mary. Stressful finals loomed for Gus, but so too did the comfort and relaxation of the holidays. Gus had started making winter break plans that included a visit to a game at FedExField with his friend Danny.

On Wednesday, November 28, 2018, Gus called home. He was lonely and homesick, he said. He was already halfway up to Vienna from Richmond. He’d be home in an hour.

Gus didn’t seem overly emotional when he arrived. Chris and Phyllis asked if got into a fight or was in trouble with his team. Gus said there was nothing wrong – he just wanted to come home. He missed his friends and family.

Sensing signs of depression, Phyllis asked Gus if he would be receptive to therapy to help him out of his funk. He obliged.

Phyllis made dozens of phone calls to try and find Gus an appointment. Most therapists’ earliest availability was in two weeks. Not soon enough. Finally, a friend’s recommendation came through. A therapist agreed to see Gus after her last patient on Thursday, November 29.

The therapist told Phyllis how Gus had characteristically done more listening than talking but agreed to continue speaking with her over the phone while he was at Richmond. Phyllis mentioned how Gus was a long-time contact sports athlete with a potential concussion history. The therapist recommended Gus should see a psychiatrist for a full screening. They scheduled the screening for Gus’ return to Vienna over winter break.

“You must be so proud of yourself.”

Gus returned to Richmond ahead of finals. Phyllis and Gus kept up their calls.

Meanwhile, Phyllis connected with Shannon St. Pierre. The friendly compliance officer became Phyllis’ eyes on the ground for Gus’ status on campus. Phyllis spoke with St. Pierre often, and asked at one point if Gus was doing well.

St. Pierre seemed surprised at the question. She saw Gus often studying with friends, appearing in good spirits. He even popped by her office to give an update on how his older sister was doing and his plans for winter break.

A call from Gus corroborated St. Pierre’s account. He told Phyllis he got a 92 on his calculus final.

Phyllis used a parenting verbiage trick to bolster Gus’ confidence.

“You must be so proud of yourself,” she told him. “People hate math!”

She was proud of him, of course. But she felt Gus needed to feel the esteem, too.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Gus was still missing. The Lees decided to go to Richmond to try and find their son. As they were about to head out, a Virginia state policeman arrived at the door and told them the devastating news. Gus was gone. He had died by suicide two nights earlier. A snowstorm in Richmond covered Gus’ car and hid it from police on their first search.

Pretending

Chris and Phyllis drove to Richmond and arrived to receive an outpouring of support from the school community. St. Pierre helped the family collect Gus’ things and meet with Gus’ coaches and the school’s chaplain.

Phyllis worried Gus’ suicide was an indicator he didn’t have many friends at Richmond. But the school gave the family a box stuffed with handwritten notes from students who knew Gus, filled with stories of how Gus made them laugh, inspired them, or had been there for them in their time of need.

The Lee family was left to wonder why Gus didn’t feel he could ask the same of his friends.

“From the outside, he seemed like he had a perfect life,” Phyllis said. “He was pretending to everybody that everything was fine.”

Searching for answers

In her sleepless nights after Gus’ death, Phyllis decided she wanted to donate Gus’ brain to the UNITE Brain Bank.

Phyllis initially donated Gus’ brain with the thought he may have had Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease caused by repetitive head impacts found in the brains of hundreds of former football players. But the more she researched the disease, the more she questioned whether Gus’ symptoms fit.

Before his death, Gus wasn’t struggling cognitively or behaviorally. He maintained good grades, had a flawless memory, and was thriving socially. Phyllis wasn’t surprised, then, at the pathology report from the Brain Bank. Dr. Russ Huber found Gus did not have CTE.

Dr. Huber’s detailed report concluded Gus’ brain exhibited many of the molecular and structural changes that precede the onset of CTE in the brain and are consistent with a history of brain trauma.

In the report, Dr. Huber wrote: It is a case that could easily have had CTE but doesn’t. I would hope that this case will be part of the resilient group that we are studying to find out what kind of genetic factors and lifestyle choices are important to prevent CTE.

Starting the conversation

While Gus’ brain was being studied, the sports community rallied around his death. Teams from across the country sent autographed footballs and jerseys to the Lees.

A.J. Mejia played football with Gus at Paul VI and went on to kick for the University of Virginia. Mejia changed his uniform number at the University of Virginia to Gus’ Richmond number 28 for the 2018 Belk Bowl. Virginia won the game 28-0.

Roman Puglise played lacrosse with Gus at Paul VI and went on to play for the University of Maryland. When Maryland played Richmond on February 9, 2019, Puglise changed his number from 8 to 23. Gus wore 23 for the Paul VI lacrosse team.

The gifts and number switches started important conversations in college locker rooms about mental health. Through tears, Puglise spoke to his Maryland teammates about the prevalence of mental illness and reinforced that it was OK for an athlete to speak up about their own mental health.

Since Gus’ suicide, the University of Richmond hired a psychologist for the athletic department.

Phyllis came to learn about the intersection of concussions and mental health. A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found the rate of suicide is twice as high for individuals who have experienced a traumatic brain injury.

“I knew that concussion was a serious issue and needed attention,” Phyllis said. “But I didn’t know that there were these other long-term dangers. And parents need to know that.”

Parents can help their children, but Phyllis and Chris want athletes to know how to help themselves. They believe athletes should tend to their mental health status as seriously as they would a sprained ankle. Gus had plenty of friends, teammates, coaches, and family that he could have confided in.

“Athletes need to know that if you play a contact sport, you’re at a higher risk for crisis,” Phyllis said. “They need to recognize how they’re feeling and then be open and honest about those feelings with others. It’s heartbreaking because we would have moved mountains and spent our last dime to get him the help he needed had we known he was in distress to this level.”

Suicide is a complex public health issue, involving many different factors. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide most often occurs when stressors exceed current coping abilities of someone suffering from a mental health condition.

The Lee family still holds the sports Gus played in high regard. Sports were central to Gus’ identity and provided him with tremendous opportunity in life. It’s their hope the millions of contact sport athletes who may be struggling know they’re not alone and that it’s OK to not be OK. They hope their honesty and sharing Gus’ story will save lives.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.