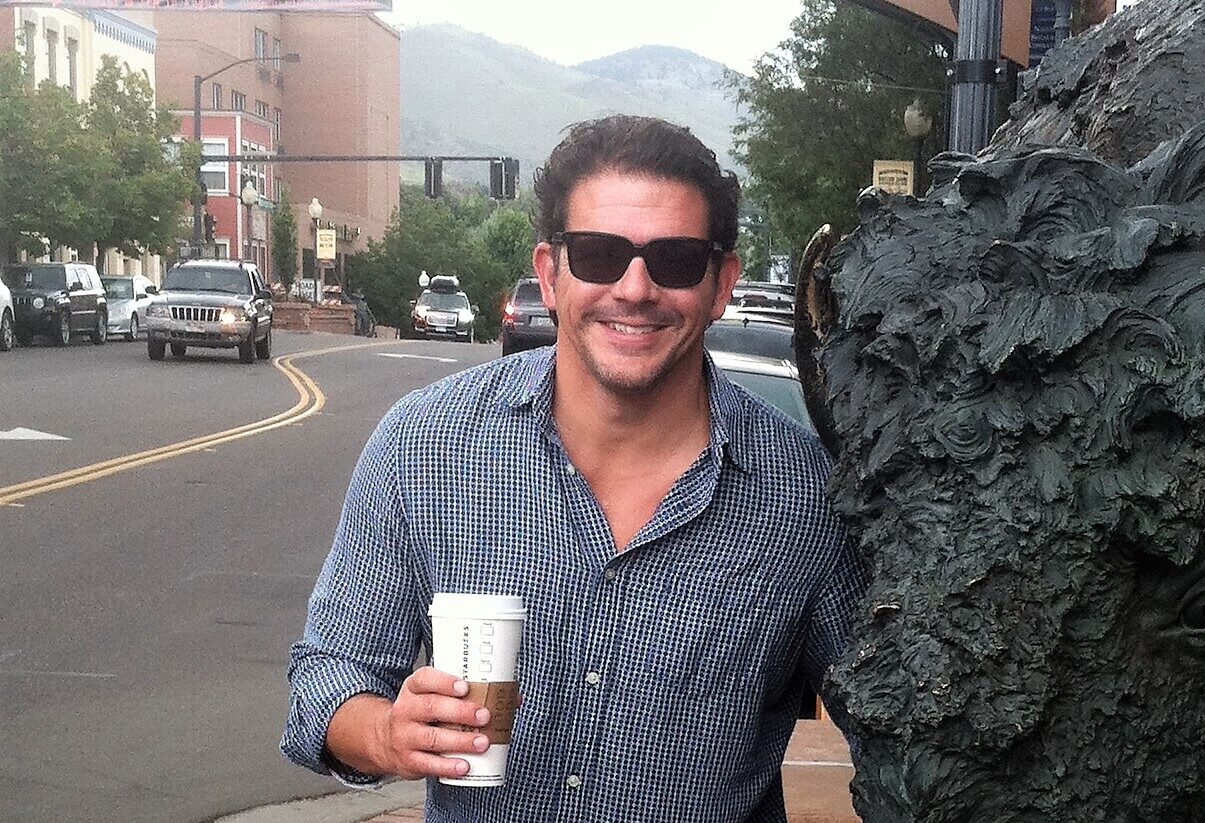

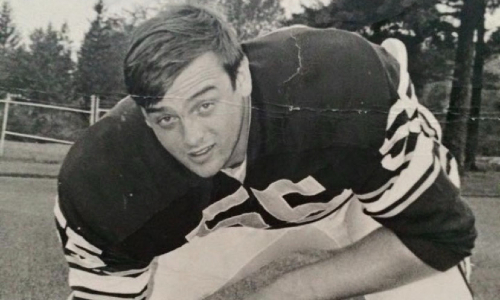

Herbert Carey Jr. was a talented athlete who played football starting in middle school and through college at the University of Maine, Orono. He was a terrific husband, father, and grandfather. Later in life, he struggled with alcoholism, impulsivity, and erratic behavior. After years of dealing with an Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis, Carey passed away on March 21, 2021, at the age of 70. His family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University, where researchers later diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) CTE. Below, his daughter Kristen shares the Legacy of her hero.

My father was one of the greatest men to ever live. He was thoughtful, kind, caring, hilarious and above all, loved his family more than life itself. Dad was my hero.

My father, Herb Carey Jr., was born on February 12, 1951, in Salem, MA and was raised in Marblehead, MA. My dad was born into a football family. My grandfather, Herb Carey, Sr. was captain of the 1950 Dartmouth College football team and was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles, though he decided not to play professionally. Ironically, my grandfather died of a brain tumor in 1983, but I often wonder what story his brain would’ve told.

From the time my father was a young boy he played football and absolutely loved the game. Dad played throughout middle school and high school, and also played all four years of his college career at the University of Maine, Orono. Throughout most of those years, my mother, Linda Hardwick Carey, was on the sidelines cheering him on.

My parents met when they were in middle school. They were married in June of 1972, the year before my father received his master’s degree. They would go on to spend 48 years of marriage together, raising two daughters and five granddaughters. But their marriage wasn’t always easy.

From the time I can remember, my father abused alcohol. Dad wasn’t aggressive, or mean, but he drank every day, and sometimes, all day. He received a few DUIs and lost his license for a period of time. I recall begging him not to drink before he came to any of my field hockey games, track meets, or before any major event, such as my prom, or family weddings. My dad finally got sober in July of 2004, three months prior to my wedding.

In addition to his battle with alcoholism, my father made some poor choices throughout the years. Dad had a temper, ironically, when he wasn’t drinking. Every once in a while he’d display erratic behavior, which became more frequent towards the end of his life.

One day, in the spring of 2012, my father was outside with my two daughters and he couldn’t recall their names. One of them is Carey, my maiden name, and the other is Hagan, his mother’s maiden name. It scared him, and it scared us, so we sought help.

In July of the same year, when my father was 60 years old, we received the punch in the gut of a lifetime: an Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis (after his death, we learned my father had stage 4 CTE). I vividly remember that day. After the appointment, I recall getting in my car, trying to process what I had just learned and wanting to throw up. The news hit me like a ton of bricks, and I had so many questions. How long would my dad live? What would his quality of life be? How would my mother handle this? How would I handle this? After all, he was my best friend. I also wondered how this happened since we don’t have a family history of Alzheimer’s. So, I couldn’t help but immediately think of the years he’d played football.

When you’re diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, you’re diagnosed with a death sentence. There has never been an Alzheimer’s survivor, and the journey for both the patient and their loved ones is the most grueling, heart-wrenching, painful experience. We know this now, because we’ve lived it. Alzheimer’s isn’t just about “forgetting” things; Alzheimer’s for us, was having to tell my dad he couldn’t work any longer and needed to retire. Then came the time we had to tell him he could no longer drive, or when we had to convince him to downsize and move out of their house because we knew it would help my mom. There was also the gut-wrenching decision of having to remove him from my parents’ home, because it wasn’t safe for my mother to be with him any longer. This wasn’t my dad; it was Alzheimer’s. I don’t wish this on anyone, and my father didn’t either. In fact, he offered to sign up for as many trials and studies at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) as humanly possible. He always said, “I know it won’t help me, but if I can be a part of something bigger, or a part of a cure so that another family doesn’t have to go through what we’re going through, then I’ll do it.”

My sister and I took turns driving my dad to and from MGH for years for him to participate in trials. I grew to love those trips to and from Boston because I was able to spend more time with him. I’ll never forget the last day of the last trial he was eligible for; the trial was over, and my father’s Alzheimer’s had progressed to a point where he was no longer eligible for trials. I remember telling him we were leaving the hospital and he asked me where his medication was (it was always handed to us in a brown paper bag). I said, “Dad, the trial is over, we don’t have any more to participate in.” He collapsed into a chair and started crying. He said, “I need the trial medication, I need to do this for your mother, I need to be here for her.” I sat next to him, we had a good cry, and I told him things would be OK.

In 2016, he told us he had made the decision to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University upon his death. My dad wanted to do whatever he could to help others, but that was Herb Carey. Dad had a heart of gold. My father showed up for everyone, especially for his wife, two daughters, and five granddaughters.

In March of 2020, just as the world was shutting down, so was my father. We had to remove him from my parents’ home (for my mother’s safety) and find a place for him to live. Little did we know at the time it would be months before we’d be able to see him or hug him again. When we were finally able to reunite, we could see the decline.

On March 21, 2021, my dad lost his battle with Alzheimer’s. We donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University upon his death and in January of 2022, our suspicions became reality. Dr. Ann McKee diagnosed my father with stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

In the end, the sport that my father loved, didn’t love him back. Instead, it cost him his life. Our hope is that with his brain donation to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, they will continue their tremendous efforts, so that one day, the world will be free of CTE.