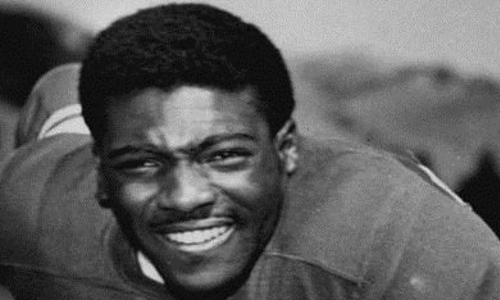

Decades after his final snap, John Henry Johnson remained a beloved NFL figure. A bruising fullback in the 1950s and 60s, Johnson quickly earned a reputation as one of the league’s toughest players, launching to stardom as a member of San Francisco’s “Million Dollar Backfield.” When John Henry was in his 50s, family and loved ones noticed issues with speech and memory, and the Hall of Famer was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1989. His daughter and caretaker Kathy donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank after his death in 2011, and researchers diagnosed Johnson with stage 4 (of 4) chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

John Henry Johnson’s remarkable journey started in 1929, in the rural town of Waterproof, La. In the segregated South, Johnson did not have the option to attend high school near his hometown, so he moved to the Bay Area to live with an older brother at the age of 16. At Pittsburg High School, Johnson played organized sports for the first time, putting together a dominant prep career as a football, basketball, and track and field athlete.

Upon graduation in 1949, Johnson chose to play football at nearby St. Mary’s College, where he made history a year later as the first Black player in program history. He was the first Black student-athlete to compete against a University of Georgia team and was carried off the field by the home fans following a standout performance in a stunning 7-7 tie against the visiting Bulldogs.

St. Mary’s discontinued its football program after the 1950 season, prompting Johnson to follow several teammates transferring to Arizona State, where he continued to play on both sides of the ball in addition to returning kicks. The San Francisco 49ers selected Johnson in the second round of the 1953 NFL Draft, and after one season in the Canadian Football League, the fullback embarked on a legendary NFL career.

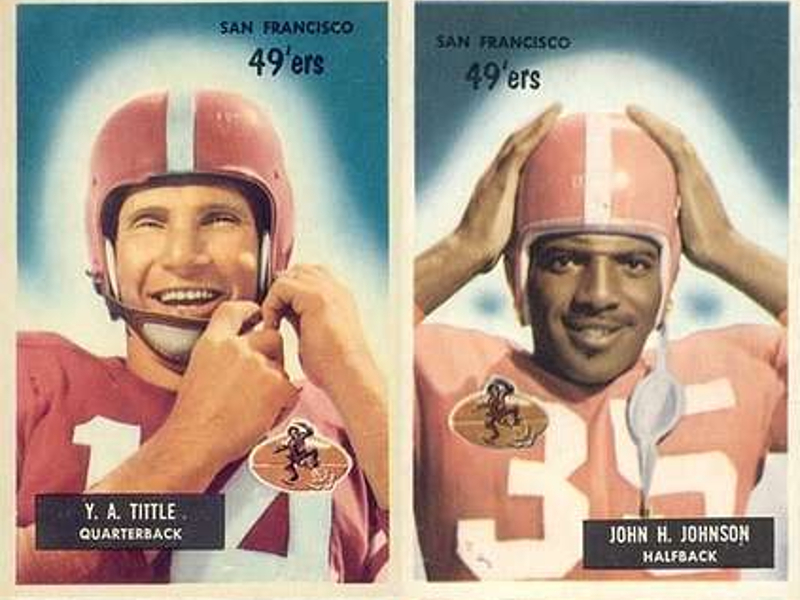

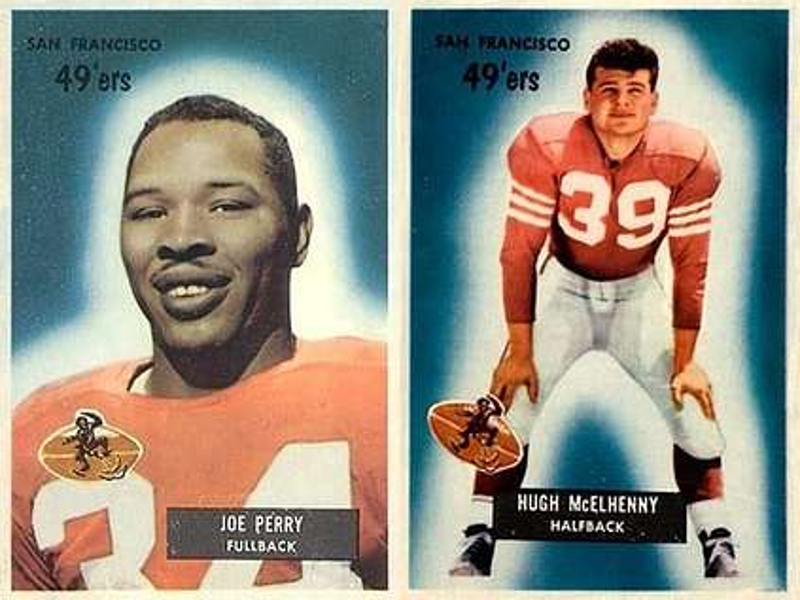

In San Francisco, Johnson joined quarterback Y.A. Tittle and running backs Joe Perry and Hugh McElhenny to form the “Million Dollar Backfield.” The four backfield mates captivated Niners fans for three seasons and are the only “T formation” fully enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

John Henry Johnson was one of four Hall of Famers making up San Francisco’s “Million Dollar Backfield.”

As his on-field success raised his nationwide profile, Johnson enjoyed raising his family when he had time away from football. John Henry’s daughter Kathy Moppin said her father loved to dance and always had a joke for his six children. She said he was proud of his place in the Bay Area community and enjoyed visiting schools with his 49ers teammates.

Kathy said because of her father’s playful demeanor off the field, she did not realize until late in his career he developed a reputation as one of the toughest players in the NFL, frequently sacrificing his body on crushing blocks and bruising runs between the tackles.

“He got hurt quite a bit,” Kathy said. “I can remember he had teeth knocked out and shoulders dislocated, and back then, they used smelling salts when they got lightheaded on the field. He went through a lot of trauma to his body.”

The 49ers traded Johnson to Detroit before the 1957 season, and that year he helped lead the Lions to their most recent NFL championship. Johnson joined the Pittsburgh Steelers ahead of the 1960 season. Though he was 31, Johnson still had his best individual seasons ahead of him. He earned the final three of his four Pro Bowl honors in his mid-30s. In 1964, at 35, Johnson became at the time the oldest NFL player to rush for 1,000 yards in a season.

When Johnson retired at 37 following the 1966 season, he ranked fourth on the all-time rushing list. He finished his career with the Houston Oilers but returned to Pittsburgh to start a new career with Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania and later with Warner Communications. Year after year, the Pro Football Hall of Fame overlooked Johnson, who was considered by peers to be one of the best all-around running backs in NFL history.

Finally, in 1987, Johnson got the call to Canton, joining his “Million Dollar Backfield” teammates in the Hall of Fame. He joked at the time that the nickname was far from literal, as he never earned more than $40,000 in an NFL season.

Back in the Bay Area, Kathy said she would speak with her father on the phone two to three times per week. However, when John Henry reached his 50s, Kathy and others close to John Henry noticed changes in his willingness and ability to communicate, on the phone and face to face. A friend in Pittsburgh called Kathy and encouraged her to check on her dad, which she did with the help of John Henry’s wife Leona.

“He still had a good sense of humor, but he was just a lot slower,” Kathy said. “It took him a while to answer if you asked him something. I noticed early on he was having some symptoms of something. I didn’t know what it was.”

In 1989, with Johnson’s cognitive issues affecting his daily life, Leona enrolled Johnson in an Alzheimer’s disease study in Cleveland. This led to a formal diagnosis, and Johnson retired from his post-playing career. Kathy said it was a difficult time for their family, with most of them more than 2,000 miles away from their dad.

“I was very sad, and my siblings were sad, too,” Kathy said. “My dad, at that point, didn’t really get a sense for how serious things were.”

Kathy said despite his struggles at home, John Henry looked forward to annual trips to Canton, Ohio for Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. Clad in their gold jackets, Johnson and his fellow Hall of Famers cherished the opportunity to reminisce about the glory days of decades past.

As the years went on, Kathy said, the late-summer tradition became an eye-opening experience for her family and other relatives of NFL alumni. In Canton, she recalled more wives, sons, and daughters privately sharing concerns about their loved ones’ health years after their football careers ended.

“Every year when I went back, there was more and more guys having symptoms like my dad,” Kathy said. “That’s what got me. Every few years, I could see the next husband with symptoms and the wife having to push him in a wheelchair.”

John Henry returned to California after his wife passed away in 2002. Kathy became his primary caretaker, which presented challenges she could only face with help from her husband and siblings.

“When you sign up for that, you don’t know how hard it’s going to be and how it changes your life,” Kathy said.

Then in his 70s, John Henry struggled further with memory and communication. Though it had been 50 years since he played for the 49ers, he still received fan mail from fans in the Bay Area. When he signed autographs, Kathy said she had to remind him which year to write under his signature when he mistakenly wrote the incorrect year of his “HOF” induction.

Johnson’s struggles with Alzheimer’s included a few instances of wandering from home, which only added stress to Kathy as a caretaker. She said she installed a bell on her front door after police returned her father, finding him waiting at a nearby bus stop. He told her he was on his way to join his Niners teammates for practice that afternoon.

“It was hard for me,” Kathy said. “It was sad to see him decline like that. I cried many a night. But all my siblings helped out, and I was able to get through it. It was sad to see.”

John Henry Johnson died in 2011 at the age of 81. At the time, the NFL’s concussion crisis and the growing understanding of CTE led Kathy to consider donating her father’s brain for study. His San Francisco teammate Joe Perry had died five weeks earlier, and with encouragement from Joe’s widow Donna, Kathy elected to donate her father’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank.

Boston University researchers diagnosed Johnson with stage 4 CTE, the most advanced stage of the neurodegenerative disease.

“It kind of gave me some closure,” Kathy said. “I was very shocked and sad to hear that, but then I understood more why my dad acted like he did.”

Kathy shares her father’s Legacy Story to celebrate his life while raising awareness about the potential long-term consequences associated with tackle football’s repetitive head impacts. While helmet technology has improved, Kathy said today’s players face most of the same risks as her father, and she hopes more parents and coaches educate themselves about CTE to help prevent similar outcomes to what her family experienced.

She hopes her father’s story leads coaches and administrators to consider policies and rule changes with long-term brain health in mind. Kathy and her family remember John Henry Johnson as a “loving, kind, funny guy,” a man who put smiles on the faces of fans from coast to coast.

“I was shocked to see so many people still remembered my father, and they remembered him as a hard player, a tough player,” Kathy said. “He loved football, and he was loved by his family.”