John Mackey was a revolutionary football player and advocate for social change. Mackey played tight end for Syracuse University and then for the Baltimore Colts and San Diego Chargers in the NFL. His decorated career his number 88 being retired by Syracuse, five Pro Bowl selections and being inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame. After his playing career, Mackey became the first president of the NFLPA. After being diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, Mackey began having issues with his memory and lost the ability to care for himself. Mackey passed away in 2011 at the age of 69. After his death, Mackey’s family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank where he was diagnosed with advanced stage Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Read how CTE affected Mackey and how his legacy of helping others continues today.

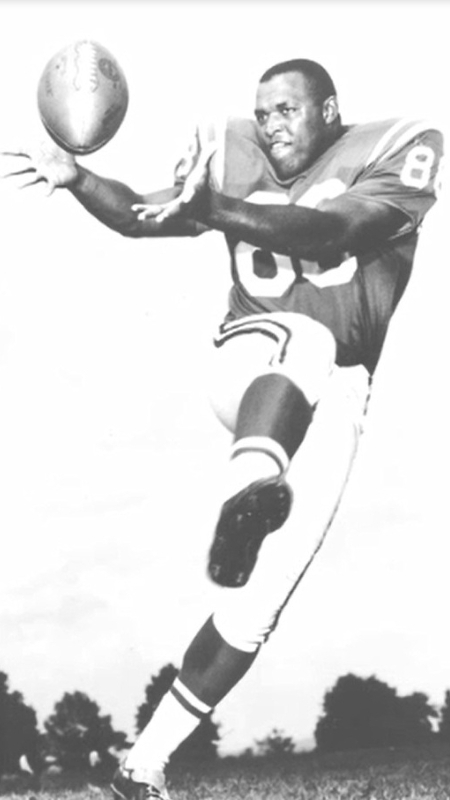

John Mackey made a difference – in football, in business, and in life. A star tight end at Syracuse University, his impact was so significant that the university retired his jersey number – 88 – in his honor in 2007. While at Syracuse, he quietly and peacefully made inroads into the discrimination that permeated society, building lifelong friendships that transcended ethnicity and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Selected by the Baltimore Colts in the second round of the 1963 draft, John played nine seasons with the Colts before finishing his playing career with the San Diego Chargers in 1972. In 10 seasons in the NFL, he earned Pro Bowl honors five times, including his rookie season. In 1992, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, only the second at his “revolutionized” tight end position to be so recognized. To this day, Mike Ditka – the first tight end to be inducted in the Hall of Fame – describes John as the greatest to ever play the game.

In 1970, John became the first president of the National Football League Players Association following the merger of the NFL and AFL. He spent the next three years leading the union through turbulent times, fighting for better pension and disability benefits for players, and gaining free agency that today’s NFL players still enjoy. It was a battle that some contend kept him out of the Pro Football Hall of Fame for 15 years.

Off the field – and for nearly three decades after his football career ended – John was as committed to advocating for those in need as he was to football – and in particular, Syracuse University and the Syracuse Orange, and Baltimore and the Baltimore Colts. Although he and former U.S. Congressman Jack Kemp (an NFL veteran himself) had different political perspectives, they partnered to launch a non-profit to give an educational advantage to disadvantaged children. He actively supported the civil rights movement that changed the course of history. He reached out to others, whether it was to offer guidance on career choices or to advocate for recognition of an under-appreciated teammate. At John’s funeral in 2011, in fact, his Syracuse teammate, former Denver Bronco Floyd Little, told mourners what John wrote to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in support of Floyd’s candidacy: “If there’s no room for Floyd Little in the Hall of Fame, please take me out and put him in.”

That’s the kind of person John Mackey was.

He was also my college sweetheart. We started dating as freshmen at Syracuse, thanks in part to our friend Ernie Davis, a teammate of John’s who loaned him the money to pay for our first date. John and I married in 1964, raised a son and two daughters together, and had just begun to enjoy our grandchildren when John was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia. He was just 59 years old.

Until then, I thought we would grow old together. I thought we would watch our children’s children grow up. Instead, over the last 11 of our 47-year marriage, I watched the love of my life lose every memory of the family, the friends, and the game he treasured. Over those 11 years between his diagnosis and death, the compassionate person who cared so much for others, the man who stood up for the underdog, the mentor who provided guidance to so many young people, the citizen who gave back to the community – the loving husband, father, and grandfather – slowly regressed to a childlike adult.

Despite the ravages of the disease, there was one constant in John’s mind – he was a Baltimore Colt. When his disease progressed to the point where hygiene became an issue, a fake message from the NFL’s then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue convinced John to brush his teeth. He proudly wore his Super Bowl V and Pro Football Hall of Fame rings, yet it was absolutely heartbreaking to hear him ask friends and fans alike, “Do you want to see my rings?” Even in the fog of dementia, the Baltimore Colts and the National Football League broke through.

Although dementia robbed John of his powerful voice, the disease gave him the ability to influence the discussion about head trauma, to inform active and former players about the dangers, and to impact the future of sports medicine and player safety. His private battle with dementia became the public face of the link between head trauma, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and related ailments. He was the catalyst for the 88 Plan that provides financial assistance for those affected, for the advocacy and fundraising efforts of his Baltimore Colt teammates that changed the conversation from blaming the player to protecting the future, and for my own involvement in the Concussion Legacy Foundation. When John died on July 6, 2011, a few months shy of his 70th birthday, the widespread media coverage focused as much on these and other post-diagnosis accomplishments as on any of his other achievements in life. Even in illness and in death, he changed the world.

That, I believe, is John Mackey’s greatest legacy. What will your legacy be?

Sylvia Mackey

Mrs. #88