Joseph Coyle was a tough but loving family man who enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17 and spent a tour of duty abroad. Upon his return, he joined the Metropolitan Police Department in Massachusetts, often getting into altercations when arresting suspects. As he got older in life, Coyle’s family noticed him having trouble with his memory as well as other changes. After Coyle’s death in September 2022 at the age of 86, his brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) CTE. Below, Coyle’s son Sean shares the Legacy of his father to help others who may also be struggling.

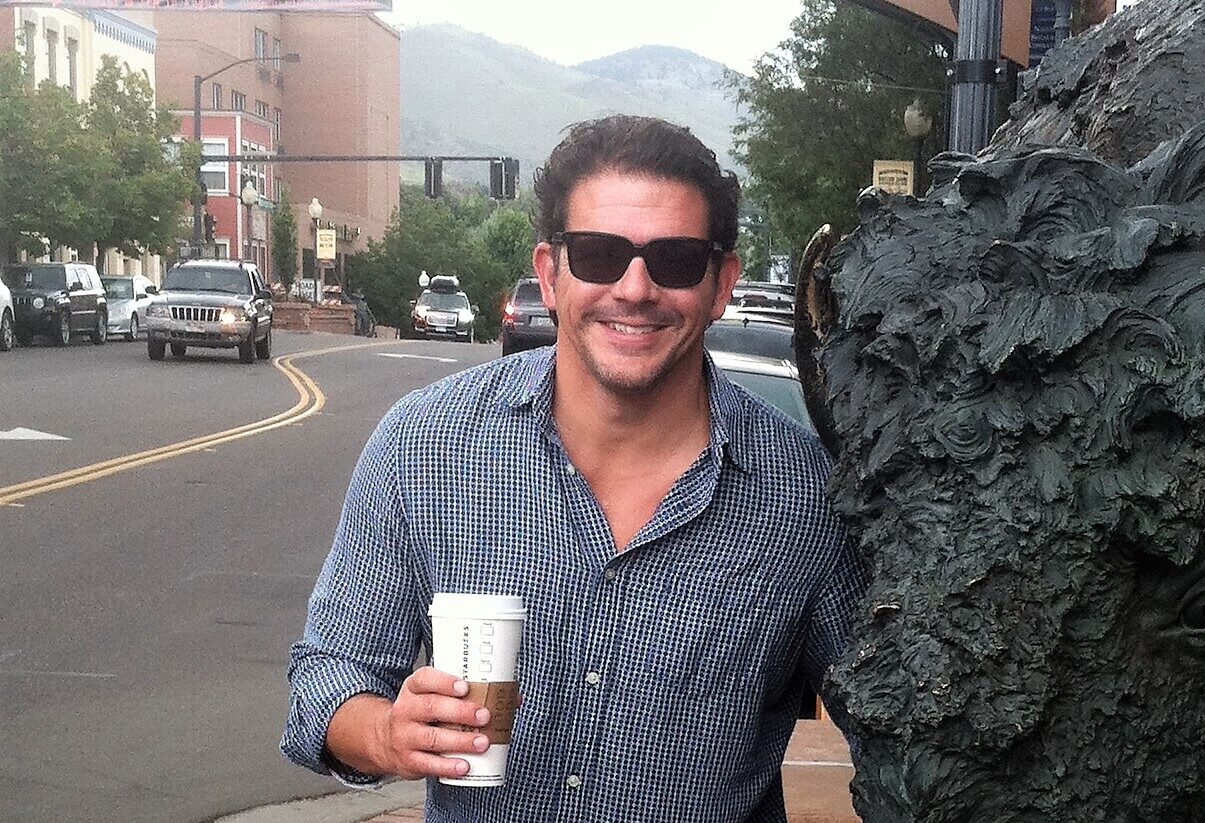

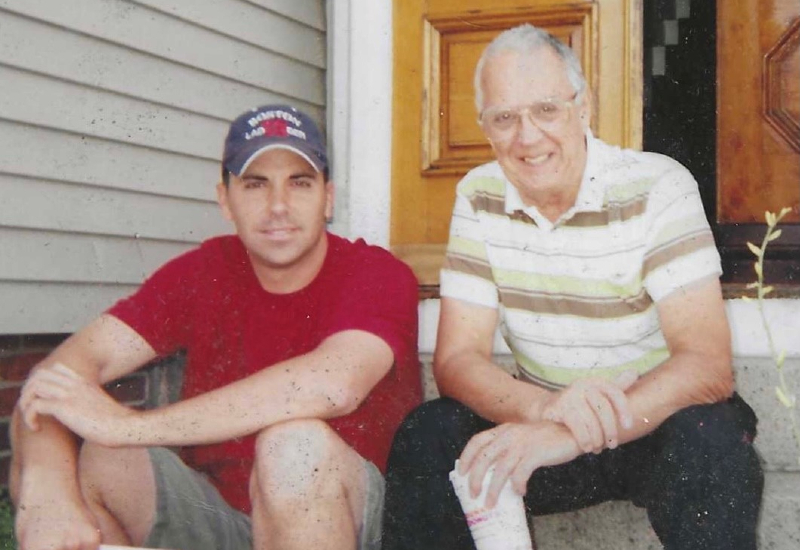

The honor of being at my father’s side when he passed on September 21, 2022, was a day I’ll hold dear the rest of my life. I felt it a privilege to be there in the final moments of a life I believe was that of a hero. For certain, he was a good man. He always tried to do his best and my earliest memories in life are of him and how good a Dad he was, how much he wanted what was best for me.

Joseph “Joe” Francis Coyle was born in the Mission Hill neighborhood of Boston on June 21, 1936. It was a tough Irish Catholic neighborhood and he was definitely a city kid. The 1940s in Mission Hill were much like the rest of America where post-Depression and WWII were the dominant forces for kids growing up. He was very intelligent, however school and academics were not his focus and he enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17.

His strong personality and being from Boston made for interesting stories, including his tour of duty in Korea. He incurred several documented injuries where he suffered head injuries, one in particular was severe and his brain/skull was operated on. He was young, strong, and recovered quickly and probably thought little of it after the fact.

After being discharged and returning home, he worked several jobs, including joining the Metropolitan Police Department (merging later with the Massachusetts State Police). The Metropolitan Police was a department that covered unique jurisdictions ranging from rural state properties to inner city patrol assignments. He did them all with the same intensity as the city kid who joined the Marines.

Before they had some of the current police equipment of today, cops in the 60s, 70s and 80s resorted to much of their suspect interactions using their hands, engaging in arrests resulting from a fight. He certainly did not back down from anyone and from all accounts was in the fight whenever needed. I’m sure he took additional brain trauma in the years he was working nights in Boston.

He was well read, well spoken, and challenged me to expand my goals and intellectual pursuits. He truly was the smartest guy I’ve ever known. He was always available for any advice I ever needed and looking back, he was instrumental in my life and successes. Whether during my time in the Marine Corps, or in college, or at a new job, or in a relationship, I could talk to him and get the advice of a dad who only wished the best for his son. I have so many memories of having a tough, but loving dad that truly wanted and prayed for my success. I’m so grateful for every day I had him and miss him still, always will.

In 2016, when he was age 80, I started to notice little things, forgetful inconsequential patterns which I wrote off to natural aging. Just a missed appointment or repeating himself or losing his train of thought easily – all of which were very new for me to see in him. Concerned enough, I moved him in with me in Boston, so I could look out for and take care of him as he always did for me.

At the time, I was a Boston firefighter and worked 24-hour shifts, but felt calling him often while at work would be OK on those days. It was only living with him that I realized it was so much worse than I thought. I was seeing how short his memory had become and when I returned home, I could tell he didn’t really know how long I had been gone. It was apparent to both of us he needed 24/7 care that I wasn’t able to give him.

Once in the care facilities in Boston, we could really see something was very off. Some medical professionals thought it was typical Alzheimer’s and/or dementia. As a firefighter I had seen a lot of both diseases and just didn’t think it fit him. I couldn’t put my finger on it, but knew it was something else.

After seeing several documentaries on CTE in football and some subsequent reading on the subject, I just knew it was the answer. I really had no doubt. I told my dad my thoughts, he would listen and agree and two minutes later he would tell me he thinks he’s having memory issues and wasn’t sure why. I’d tell him about CTE and he would listen and agree – and two minutes later tell me he thinks his memory is failing and he’s not sure why.

I researched BU’s Brain Bank and made a point of telling my dad more than ten times over several months I wanted us to donate his brain for study. We had a laugh once when I told him again about the plan and he sat up and said, “When?!?” I told him, “After you pass.” “Oh that’s fine,” he replied back. I can still hear his laugh, so genuine, just wanting to enjoy the company with him and make sure everyone around him felt good.

Within an hour of his death, arrangements were made with the amazing and dedicated scientists at BU to harvest and study his brain. I was hopeful, if my suspicions were found to be true, some good needed to come from his donation.

In the week between his death and funeral, friends of mine from the military and fire department started gathering to recall stories of my dad and begin to assist me in laying him to rest. It was an honor to have them, heroes of mine, to help me in giving the first hero of my life the burial honors he earned and deserved.

The researchers got back to me once my dad’s study was complete and told me they found stage 4 (of 4) CTE. It was comforting to know the answer as to what had been impacting his final years. To have my friends, all serving in those very roles he served in, carrying his casket I immediately knew I wanted his life and service to continue in the Legacy efforts to help others. I look forward to sharing my dad’s story so military members returning home or young cops on the job might be more aware of the critical education and care needed for themselves and their peers, regarding brain injuries resulting from work related traumas.

The effort was best summed up when I told Congressman Seth Moulton about the report findings and my hopes for my dad’s story helping others: “And now he continues to serve others!” I look forward to the path ahead, gaining education and working together to advance awareness and policy to care for those who protect us everyday.

Maybe my next conversation with Congressman Moulton will be more formal.