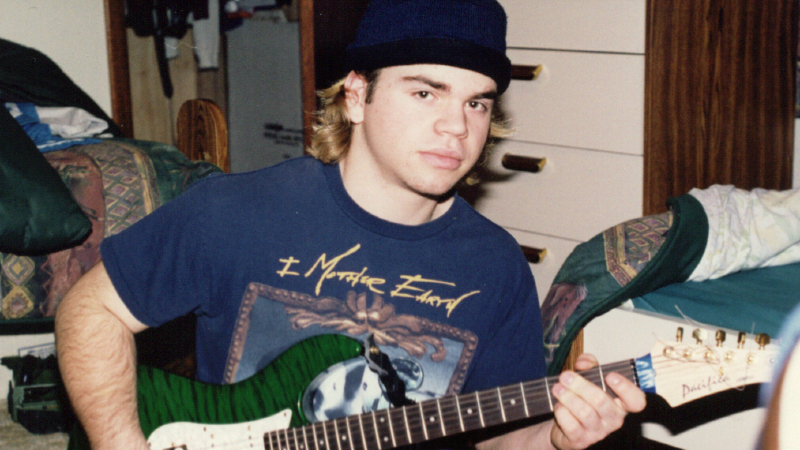

Lyndon Kenny was an imposing hockey enforcer on the ice and a lovable teddy bear off of it. He grew up in Saskatchewan, Canada and started playing hockey at age 5. Kenny reported hundreds of blows to the head in his hockey career. Late in life, Kenny battled substance abuse and reported how he suffered from a litany of Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) symptoms, including anxiety, depression, sleep issues, and headaches. On November 1, 2011, Kenny took his life at age 27. His brain was later studied at the UNITE Brain Bank where Dr. Ann McKee diagnosed him with stage 1 Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Four months after Kenny’s death, his brother Sheldon wrote a story for his school newspaper about Lyndon Kenny’s life and concussions and CTE in hockey.

The following was written by Sheldon Kenny, Lyndon’s brother four months after Lyndon’s death. Sheldon’s story originally appeared in The Sheaf, the University of Saskatechwan’s student newspaper in March 2012.

This past November I lost my brother Lyndon Kenny to suicide.

Lyndon was a very good hockey player. He was drafted by the Brandon Wheat Kings of the Western Hockey League and he was not only a highly-skilled defenceman and strong skater, but also the toughest person I have ever known.

His ability to scare opponents and produce game-changing hits and fights was unparalleled for someone of his age.

Unfortunately, this enforcer style of play made my brother vulnerable to multiple concussions and, therefore, more susceptible to depression.

Enforcers are the designated tough guys on a hockey team. Players in this role often struggle with depression not only because they suffer numerous and severe head injuries, but also because they must deal with the pressure of fighting almost every game in order to keep their spot in the lineup.

Lyndon was no exception.

My brother became addicted to alcohol and drugs at an early age. His addictions carried on through most of his life, even with multiple stints in rehab centres.

He was not a drug addict like those on TV shows, though. He hardly let it show in his personal life. He was the most loving and caring person I knew and was constantly looking out for others.

He struggled to explain his problems to me and our family, however, and for a long time he turned away from those closest to him — as the archetypal tough guy, he tried to cope with his struggles alone.

It was only recently that Lyndon came to understand that he needed help. He began to open up to our family and made an effort to guide me down a better path of life than he had taken.

He had been drug- and alcohol-free for two months before he took his own life on Nov. 1.

The depression and anxiety proved too much for him.

Only a few weeks before his death, Lyndon left a comment on a sports medicine website indicating his struggles.

“I’m 27 and have been on a serious decline since [my] early to mid teens,” my brother wrote.

“I have had hundreds of blows to my head since I was around age five. Most occurred from my reckless style of hockey throughout my teens. Here’s a list of symptoms I have — Lack or loss of knowledge, insight, judgement, self, purpose, personality, intelligence, opinion, reasoning, train of thought, motivation, relationships, thinking, humour, ability to process information and learn, organize, planning, communicating, finding speech, decision making, visualizing, interest, sensitive to sound, ears ring, trouble sleeping, head aches, PCS [Post Concussion Syndrome] etc.”

Lyndon’s comment ended with an appeal: “Protect yourselves and loved ones! What a scary situation. I feel so bad for my family.”

His final wish came in the form of an unsent text message intended for me. Lyndon wanted to have his brain donated to research at the Boston University School of Medicine so we could have the answers he had sought for years.

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Lyndon was adamant that he suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

He knew everything about it and the pursuit of the answers he needed led him to many medical professionals who could have helped him. However, he was extremely frustrated by every doctor’s complete refusal of his claims and he was angry with himself because he felt like he could not explain to them exactly how he was feeling.

It has recently been released that legendary professional hockey players Bob Probert and Derek Boogaard both suffered from extreme cases of CTE, which is no doubt directly related to their roles as enforcers.

When a team needs something to give them a momentum boost, enforcers are counted upon to go out and get a big hit or to get in a fight. This physical playing style leads to more blows to the head, resulting in concussions.

But the evidence does not stop with Probert and Boogaard. Rick Rypien and Wade Belak both died by suicide this past summer after lengthy battles with depression. Both players played a tough game and they no doubt suffered many concussions.

While we have yet to hear the results of the tests performed on Lyndon’s brain at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy in Boston (now the UNITE Brain Bank), it is obvious looking back at all the conversations we had and the symptoms he listed that he had battled with CTE for a long time. Update: Lyndon Kenny was diagnosed with stage 1 CTE at the Brain Bank.

Sadly, there is no known way to reverse the effects of concussions. Even sadder is the fact that CTE can only be diagnosed after death.

As of 2009, only 49 cases of CTE have been researched and published by medical journals.

However, the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy recently began a clinical study of over 150 former NFL athletes aged 40-69 and 50 athletes of non-contact sports of the same age, all of which are still alive and participating in sport. The goal of the study is to develop methods to diagnose CTE before death, which can hopefully lead to a cure in the future.

The future

After witnessing my brother go through all he did, all I want is to see a higher level of understanding for concussions. They can be deadly.

The cultures of all sports, not just hockey, need to change to adjust for this growing problem. Most importantly, the stigma of being the one to leave a game due to a concussion needs to stop because, in hindsight, the ones who take a step back and admit that there is something wrong are the tough ones.

I would be lying if I said I was not scared for myself.

I’ve played a lot of hockey in my life, have suffered a number of hard hits to the head and have been knocked unconscious twice.

In the past few years I have dealt with depression and anxiety and, although it can’t be proven, the fact that they may be a result of my concussions is a very real possibility.

I have also started to notice that I am dealing with some of the same symptoms that my brother felt he was experiencing. I have noticed a loss of personality, intelligence, motivation and humour. My ability to learn and communicate has decreased and I have had trouble sleeping.

I hope for my own and my family’s sake that I am simply reacting to the loss of my brother, but right now I cannot be certain.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.